|

National Sustainable Development Frameworks

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The feature article this month is the editor's review of the following book:

Hatched: The Capacity for Sustainable Development

Edited by Bob Frame, Richard Gordon, and Claire Mortimer,

Landcare Research (Manaaki Whenua), Lincoln, New Zealand, 2010

This book is about a research program on the national sustainable development outlook for New Zealand. It is an important book because it may serve, at least to some extent, as a model for similar research programs that might be undertaken by other nations. The book review is organized as follows:

1. Aim, Outline, and Overview of the Book

2. Text, Boxes, Figures, References, Links, Index

3. A National Sustainable Development Strategy for New Zealand

4. Capacity for Sustainable Development in Developed Nations

5. Capacity for Sustainable Development in Developing Nations

6. Limited Coverage of Distributive Justice and Gender Equality Issues

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

This issue includes two supplements:

Supplement 1: Advances in Sustainable Development, is a monthly snapshot of significant recent contributions to in-depth understanding of the sustainable development process, as well as recently developed analysis. This monthly selection intends to reinforce the notion that human development (including spiritual development) is the most crucial dimension of the process. The outline for Supplement 1 is as follows:

1. Suggestions for Prayer, Study, and Action

2. News, Publications, Tools, and Conferences

3. Advances in Sustainable Development

4. Advances in Integral Human Development

5. Advances in Integrated Sustainable Development

6. Recently Launched Games and Simulation Tools

7. Visualizations of the Sustainable Development Process

8. International Ecumenical Peace Convocation (WCC 2011)

9. Sustainable Development and the "Second Wave" of System Dynamics

Supplement 2: Directory of Sustainable Development Resources is an update of the directory of selected online content introduced in the January 2010 issue, with links listed under the following categories:

1. Population and Human Development

2. Cultural, Social, and Security Issues

3. Financial, Economic, and Political Issues

4. Ecological Resources and Ecosystem Services

5. Renewable and Nonrenewable Energy Sources

6. Pollution, Climate Change, and Environmental Management

7. Land, Agriculture, Food Supply, and Water Supply

8. Current Outlook for the Planet and Human Civilization

9. Transition from Consumerism to Sustainability

The invited papers this month are the following:

Millennia 2015: Women actors in solidarity, by Marie-Anne Delahaut (Page 2)

Living in Borrowed Times, by Chuck Collins (Page 3)

Making "Green" Organizations Multicultural, by Jim Bonilla (Page 4)

The Impact and Design of the MDGs, by Richard Manning (Page 5)

|

|

This book is a significant contribution to sustainable development in both developed and developing nations. Even though it is based on the New Zealand experience, most of the material should be of interest to sustainable development professionals everywhere. The book covers the social, economic, environmental, and cultural dimensions of the sustainable development process. Tailoring the Hatched capacity building model for other countries would require case examples that fit the social, economic, environmental, and cultural realities of each country. A more explicit elaboration of distributive justice and gender equality issues would be indicated for most countries. Also desirable would be restating sustainability and sustainable development concepts (and case examples) in terms that include social maturity factors such as practicing the principles of solidarity and subsidiarity. Otherwise, the learning concepts and sustainable development practices documented in Hatched are universally relevant.

|

1. Aim, Outline, and Overview of the Book

This book is a solid contribution to sustainability science and sustainable development practices. To learn from this book, however, it is important to understand how this book came about. The content is the culmination of several years of work, starting in 2002 with a proposal developed by the editors (who are scientists at Landcare Research, Lincoln, New Zealand) for a research project on "Building Capacity for Sustainable Development." It should be noted that Landcare Research is a government owned entity that operates as a commercial entity albeit adhering to social corporate responsibility (CSR) principles. The project was approved and funded by the Government of New Zealand in 2003, to be performed during the 2003-2009 time period. Following six years of work by the three editors and thirty contributing authors, the book was published 3 February 2010.

The objective of the book is explained in the media release:

|

New e-book ponders New Zealand's future

Media Release: Wednesday, 3 February 2010

Developing new ways to live and do business will be the defining challenge of our age, say the authors of an innovative e–book.

|

Hatched: the capacity for sustainable development is edited by Landcare Research scientists Bob Frame, Richard Gordon and Claire Mortimer and is a collection of research findings, stories and tools exploring five key areas of capacity required for New Zealand’s long-term success. It covers innovative research undertaken with businesses, across policy sectors, communities and individuals and was funded by the Foundation for Research, Science and Technology.

The book is named after a quote by author

C.S Lewis:

“It may be hard for an egg to turn into a bird: it would be a jolly sight harder for it to learn to fly while remaining an egg. We are like eggs at present. And you cannot go on indefinitely being just an ordinary, decent egg. We must be hatched or go bad.”

Author Bob Frame says more than 30 years of scientific evidence shows the trajectory the developed world has pursued cannot be sustained and developing new ways to live and do business will be the defining challenge of our age - our last chance to hatch or go bad.

Hatched explores five key areas needed to make this transformation:

|

HATCHED BOOK COVER

|

- Thinking and acting for long term success - how can NZ become a future maker not a future taker?

- Businesses as sustainability innovators - how can businesses improve, and market their sustainability performance?

- Individuals as citizen consumers - how to equip individuals to live as citizens of a sustainable society?

- Facing up to wicked problems - how can we create solutions to complex, value-laden, multi-party problems?

- The future as a set of choices - what are the next steps for sustainable development practice?

“As society grapples with the immensity of global change issues, there is an increasing demand for sound technological solutions and New Zealand is well placed to provide these through its mix of innovation, insight and strong relationships between business, government and researchers,” Mr. Frame says.

Hatched has been written for practitioners working within the public, business and community sectors and is free to download at www.hatched.net.nz The screen friendly version has hyper-links to key research papers and websites.

|

|

The outline of the book is as follows:

Front End Acknowledgments

List of Contributors

Introduction - C.S. Lewis' Egg Metaphor for Sustainable Development ~ Claire Mortimer, Richard Gordon, and Bob Frame

The book was written by 30 authors and has 5 sections and 29 subsections, as follows:

SECTION ONE - THINKING AND ACTING FOR LONG-TERM SUCCESS

Chapter 1: New Zealand, new futures? ~ Bob Frame and Stephanie Pride

Chapter 2: 100% Pure Conjecture - the Scenarios Game ~ Rhys Taylor and Bob Frame

Chapter 3: The Auckland Sustainability Framework ~ Bob Frame, Claire Mortimer, and Sebastian Moffatt

Chapter 4: Creating futures: integrated spatial decision support systems for local government ~ Daniel Rutledge, Liz Wedderburn, and Beat Huser

Chapter 5: Successful cities in the 21st century ~ Megan Howell and Claire Mortimer

SECTION TWO - BUSINESS AS SUSTAINABILITY INNOVATORS

Chapter 6: Foodmiles: fact or fiction? ~ Sarah McLaren

Chapter 7: Changing the game: organizations and sustainability ~ Nick Potter and Jonathan King

Chapter 8: Our journey from unsustainability: reporting about Landcare Research reports ~ Judy Grindell and Richard Gordon

Chapter 9: Coming of Age: a global perspective on sustainable reporting ~ Allen White

Chapter 10: Sustainability and Maori business ~ Garth Harmsworth

Chapter 11: Life Cycle Management ~ Jake McLaren and Sarah McLaren

Chapter 12: carboNZero Programme ~ Ann Smith and Kathryn Hailes

Chapter 13: Greening the Screen ~ Nick Potter and Jonathan King

SECTION THREE - INDIVIDUALS AS CITIZEN CONSUMERS

Chapter 14: Sustainable consumption ~ Helen Fitt and Sarah McLaren

Chapter 15: We are what we buy - aren't we? ~ Claire Mortimer and Wokje Abrahamse

Chapter 16: Seeking pro-sustainability household behaviour change ~ Rhys Taylor and Will Allen

Chapter 17: Supporting practice change through transformative communication ~ Chrys Horn and Will Allen

Chapter 18: Education for sustainability in secondary schools ~ Melissa Brignall-Theyer, Will Allen, and Rhys Taylor

SECTION 4 - FACING UP TO WICKED PROBLEMS

Chapter 19: Sustainability Technologies 101: 'Wicked problems' and other such technical names ~ Bob Frame

Chapter 20: Governmentality 101: Looking through a government lens - a bit more theory ~ Bob Frame and Shona Russell

Chapter 21: Water Allocation: Canterbury's wicked problem ~ Bob Frame and Shona Russell

Chapter 22: Social Learning - a basis for practice in environmental management ~ Margaret Kilvington and Will Allen

Chapter 23: Sustainability Appraisal: Evaluating proposals for sustainability assurance ~ Martin Ward and Barry Sadler

Chapter 24: Getting under the bonnet - How accounting can help embed sustainability thinking into organisational decision making ~ Michael Fraser

Chapter 25: Stakeholder analysis ~ Will Allen and Margaret Kilvington

Chapter 26: Supportive effective teamwork: a checklist for evaluating team performance ~ Margaret Kilvington and Will Allen

Chapter 27: Comparison of National Sustainable Development Strategies in New Zealand and Scotland ~ Bob Frame and Jan Bebbington

SECTION FIVE 5 - THE FUTURE AS A SET OF CHOICES

Chapter 28: Sustainability: a conversation between business and science ~ Helen Fitt and Jonathan King

Chapter 29: Sustainable Development: responding to the research challenge in Aotearoa New Zealand ~ Richard F. S. Gordon

Unending - "Sustainability is unending" ~ Richard Gordon, Bob Frame, and Claire Mortimer

Back End Acknowledgments

|

It is noteworthy that this e-book is a FREE DOWNLOAD. The concise (2 pages) introduction further defines the aim of this work:

|

The aim of this book is to provide a representation of research findings in an accessible form for practitioners within the public,

business and the wider community sectors. We hope readers will delve deeper into the academic papers listed at the end of

each chapter. There is much more available on our website and we invite readers to contact our lead authors for our most recent work.

This book does not pretend to cover all aspects of sustainability. It leaves out many great ideas, experiments and successes. It

does not address biophysical science, for example in climate change, biodiversity, soils, land and urban ecosystems; that is a

feature of the work of New Zealand’s Crown Research Institutes.

Instead our research has focused on supporting New Zealand’s and international capacity for sustainable development. We believe that capacity has now, in C.S. Lewis’s words, begun to hatch. We hope the insights within this book will continue to help individuals, organisations and communities to transition from the potential of the egg to the flight of the bird.

|

The few words highlighted (by the reviewer) in red indicate the dual foci of this review. The book is clearly about building the capacity for sustainable development in New Zealand. But the book's title seems to imply no restriction to New Zealand. Can the reader find, in this book, a framework that could be adapted to other developed countries? What about applicability to developing countries? This is an important question, since New Zealand is just one village in the "global village." Another important question is about the meaning of "capacity for sustainable development." Sustainability is hard to define. Sustainable development is even harder, as it contains the much discussed ambiguity about "sustainable economic growth" versus "sustainable human/social growth compatible with finite natural resources." This begs the question, "what is "capacity for sustainable development"? The book provides an excellent basis for discussing these questions.

Some people think that, if sustainable development means sustainable economic growth in the sense of sustainable material consumption growth, then the term "sustainable development" is an oxymoron. They are often regarded as "pessimists" by the "optimists" who remain convinced that technological breakthroughs will make it possible for material consumption growth to go on indefinitely and without irreversible damage to the human habitat. And, between the pessimistic and optimistic extremes, most people are still trying to understand whether or not some kind of transition will be required, and what that transition will entail.

This reviewer belongs to the large majority who is still confused and trying to follow the I Nga Wa O Mua path of the Maoris: "to look in front of us and to the past for guidance." In the midst of the confusion, it does seem that some kind of transition will be required and will entail both mitigation and adaptation of human consumption patterns. The book would seem to support that position; else, why the need to hatch and learn to fly? It is assumed that homo economicus is still homo sapiens sapiens and therefore capable of both moderation and innovation, even though most will overcome their "resistance to change" only when they are hit in the pocketbook. On this basis, the questions posed about the book in the preceding paragraph can be restated as follows:

- Are the book contents useful for other developed countries?

- Are the book contents useful for developing countries?

To begin with, the title of the first section is very educational and universally so: "Thinking and acting for long-term success." This goes against the common homo economicus practice of ensuring the profitability of a business "one quarter at a time." Business decisions driven by quotas for short-term profits, and consumer decisions driven by an insatiable desire for instant gratification, are incompatible with sustainable development - plain and simple. The "Unending" section at the end is very insightful and is, again, universally applicable. "Sustainability is unending." Between the introduction at the beginning and the unending epilogue at the end, the book offers abundant evidence that adopting a long view of time, and giving up delusions about "fixes" that promise definitive solutions in short order, are both indispensable to grow in the habit of balancing individual desires and the common good; and both are, therefore, universally indispensable for human-centric sustainable development.

Section 1 contains the argument for long term planning, and includes examples of gaming scenarios and such as the Auckland Sustainability Framework with a 100-year planning horizon. Section 2 is on sustainable production, mitigation practices, and the Maori business model ("Care for the land, care for the people, Go forward"). Section 3 is on sustainable consumption and consumption behavior patterns by individuals and groups. This section also includes suggested strategies and practices for behavior modification pursuant to sustainability. Section 4 is about analyzing and seeking solutions to "wicked problems," a term that refers to the complexity of problems that emerge at the intersection of social, economic, environmental, and cultural systems, with "wickedness" increasing from the local to the national and global levels. Lamentably  , a 100-year sustainable development plan for the entire world is not included. But Section 5 is a reassuring confirmation that homo economicus is still homo sapiens sapiens and, even though we often behave irrationally, reason prevails in the long term; especially if reason is properly incentivized. , a 100-year sustainable development plan for the entire world is not included. But Section 5 is a reassuring confirmation that homo economicus is still homo sapiens sapiens and, even though we often behave irrationally, reason prevails in the long term; especially if reason is properly incentivized.

2. Text, Boxes, Figures, References, Links, Index

This section is a brief evaluation of the book components, i.e., front matter, text, boxes, references, and illustrations embedded in the text.

- Cover - The painting Hatched, by Penny Howard, provides a stunning visualization of the C.S. Lewis quote that captures the essence of the book. By just reading the quote and looking at this painting, the reader gets a crash course on the book's content.

- Text - The text is written at a professional level, but sanitized of technical mumbo-jumbo and pseudo academic parrot talk. The text is presented in chapters that are 10 to 15 pages long. The main body of the book is preceded by acknowledgements, a list of the contributors, and the table of contents. The book is organized under 5 sections and 29 chapters (see the book's outline in section 1 of this review).

- Boxes - Each chapter starts with a concise summary and includes very informative and well written summary boxes. After reading the summary and the boxes, the reader may be tempted to skip the chapter. Read the summary and the boxes first if you want, but then read the entire chapter.

- Tables and Figures - Each chapter also includes one or more tables and illustrations. The design of each page is a work of art. Again, take a look at the tables and illustrations first if you want, but resist the temptation to skip the text after looking at the boxes, tables, and figures. This editor is aware that most subscribers are very busy people. Reading this book is not a waste of time.

- References and Links - There is a list of references at the end of each chapter. Many of the references are enhanced with hot links, but some of the links yield a 404 error ("Sorry, that page could not be found"). This could be an irritant for the serious online researcher.

- Glossary and Index -A glossary of the many Maori expressions used in the book translated to English would have been helpful to readers from other countries. The lack of an index at the end is strange given the high quality of the book. This reviewer has the (bad?) habit of looking at the index first, searching for keywords generally related to sustainability. Of course, the Adobe search function can be used to search for keywords and expressions. But an index at the end is useful, not only to find specific topics, but to get an idea of what is really important to the authors.

- Printing - The printed hard-copy book is a treasure. Downloading the book (a 6.25 MG PDF file) may be difficult for those who do not have a broadband connection. Once downloaded, the book is very readable on the screen if you set your Adobe Reader at 100% resolution. Printing the book locally requires a laser printer; else, be prepared to consume lots of ink and 300 high quality sheets of paper. The book is really designed for online view, and this is the best way to enjoy reading it unless you have strong preference for paper.

Either on paper or in Adobe, it is not difficult to navigate through this book. The chapters do not have to be read in sequence, but reading together all the chapters grouped under the section headings is recommended. This is a book to be kept on your desk top during 2010 and beyond. Now, given that all the required scaffolding seems to be in place and is of the highest quality, what about the substantive content of the book?

3. A National Sustainable Development Strategy for New Zealand

The Sustainable Development Programme of Action (SDPOA), was published in 2003 by the New Zealand Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, and is the official National Sustainable Development Strategy (NSDS) for New Zealand. This book is based on the 2003 NSDS, a 2006 revision, and additional work by Landcare Research up to January 2010. The development of these NSDS documents was called for by the Earth Summit, United Nations Agenda 21 (Chapter 8), Rio de Janeiro, 1992, and again by the World Summit on Sustainable Development, United Nations Agenda 21, Johannesburg, 2002. The following map shows reported global NSDS activity as of 30 April 2008:

Reported Status of National Sustainable Development Strategies as of 30 April 2008

Colors: Green = NSDS being implemented, Brown = NSDS development in progress,

violet = No NSDS, Yellow = No information available

Source:

United Nations Division of Sustainable Development

See also the Background Note

This book is the fruit of six years of research funded by this programme. The book clearly shows that, while New Zealand is a small country in terms of territory and population, it is a big country in terms of human and social capital. Surely, a book like this could not be "hatched" in countries where a large percentage of the population is illiterate and live in poverty. Only a country where most people are highly educated and living way above the two dollars per day poverty level can afford to think about building further "capacity for sustainable development" by growing in "futures literacy." And sustainable development is about the future, so the book is especially valuable by showing what it means to be on the cutting edge going forward.

New Zealanders should count their blessings. They should feel proud, and privileged, to be in a position of leadership. Judging by the impressive range of "capacity building" initiatives reported in this book, it is hoped that they recognize the heavy responsibility they have to foster the "partnership for development" (Millennium Development Goal 8) that will be required to undergo the global transition to sustainability in a civilized manner. Let's consider what they have in mind for New Zealand:

Section 1, "Thinking and acting for long term success," starts with a proposal to build "futures literacy" in New Zealand. The term "futures literacy" basically means "the capacity to think about the future," but it should lead to both thinking and acting in the present with both the present and the future in mind. Such capacity is acquired in three successive levels (Hatched, page 7, box 1):

|

Level 1 - Futures Literacy is largely about developing temporal

and situational awareness of change which enables people

to shift tacit knowledge about preferences and expectations

into a more explicit form, and thus ‘address similarities and

differences and negotiate shared meaning’.

Level 2 - Futures Literacy demands the ability to put

expectations and values aside and engage in ‘rigorous

imagining’ (which includes the discipline of social science

modelling, but without causal or predictive ambitions) to

construct a set of framing assumptions for the creation and

exploration of possibilities.

Level 3 - Futures Literacy requires the skills to reintroduce values

and expectations to support decision-relevant insights.

|

The following are considered (Hatched, page 15) to be preconditions for further progress:

|

An institutional landscape equipped to handle

uncertainty where stakeholders can draw on futures

literacy to respond to changing external pressures and

where solutions reside across agencies, both public and private

Widespread capability to accommodate both short- and

long term-views (including end-users strategic thinking capability)

A critical approach that ensures insight into the values and

assumptions that structure the present

|

It would seem that this proposal requires "futures literacy" to be acquired by most (if not all) citizens; else, how could it become institutionalized? A tall order indeed. But, in addition to the Auckland Sustainability Framework already mentioned, the book reports on gaming scenarios for groups, and decision support systems for institutions, as already being in the works to support the national learning process. Very impressive.

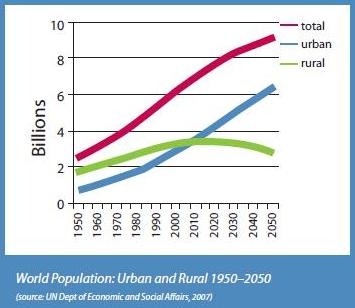

The last chapter of this section is on sustainable urbanization. It assumes that "the future will be urban" and describes how cities can be sustainable and generally successful in meeting human needs. The chapter starts with the following chart (Hatched, page 45, box 1), which seems accurate from 1950 to 2010 and very reasonable beyond 2010:

World Population: Urban and Rural Trends/Projections, 1950-2050

Source: World Urbanization Prospects,

United Nations Dept of Economic and Social Affairs, 2007.

Somewhere in the book it is acknowledged that futures literacy is not a mere extrapolation of recent trends. Granted that the sustainability of cities is crucial for the future, it is hard to imagine the persistence of trends toward even more urbanization. In order to reduce long supply chains and ensure city dwellers access to nature (and rural people access to urban resources), isn't it reasonable to hope for balance between rural and urban development? A more desirable scenario might be as follows:

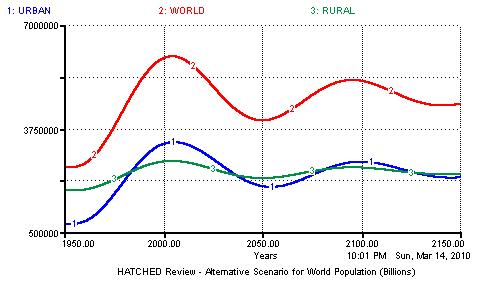

World Population: Alternative Urban and Rural Trends/Projections, 1950-2050

Note:

STELLA was used to generate the projections beyond 2010

This simple simulation envisions the following:

- World population overshooting and decreasing toward a long-term equilibrium level of about 6 billion people (with some oscillations, due to "rebounds," anticipated during population degrowth).

- Global urban population peaking and then decreasing because, among other things, 10 million people cities are hard to manage, let alone managing them for sustainability.

- Global rural population decreasing decreasingly and eventually bouncing back, as there is a need for people to care for the soil, produce food, and manage ecosystem services.

- A long term equilibrium of 3 billion urban people and 3 billion rural people for a total world population of 6 billion (some might prefer the total sustainable world to be 5 billion or less, but that's another discussion).

Sounds crazy? Who knows, perhaps some day homo sapiens sapiens may come to the conclusion that one million people cities are optimal for sustainability, and national strategies for sustainable development might include developing many such cities surrounded by rural areas. 100% pure conjecture? Certainly, but .... Auckland has 1.4 million people, Wellington has 0.4 million .... is there any 10 million people city in New Zealand? Any 5 million people city? According to Wikipedia:

|

"New Zealand is a developed country that ranks highly in international comparisons on human development, quality of life, life expectancy, literacy, public education, peace, prosperity, economic freedom, ease of doing business, lack of corruption, press freedom, and the protection of civil liberties and political rights. Its cities also consistently rank among the world's most liveable."

|

And they are surrounded by beautiful countryside. But for cities like Caracas and Sao Paulo, the surrounding countryside is not beautiful. Will the planet's human population grow to 10 billion people by 2030? Hope not. One billion people alive today are slum dwellers, and there may be two billion by 2030. Will the future be urban .... or even mostly urban? Hmmm .... hope not.

Section 2, "Business as sustainability innovators," develops the theme of sustainable production. The eight chapters in this section cover the following topics:

- Chapter 6 -- Supply chains and New Zealand's geographic location/agricultural exports

- Chapter 7 -- Organizational adaptability and change dynamics

- Chapter 8 -- Sustainability reporting by Landcare Research NZ Ltd

- Chapter 9 -- A global perspective on sustainability reporting and transparency

- Chapter 10 -- The "Maori Business Model" and management for sustainability

- Chapter 11 -- Life Cycle Management and the Formway case example

- Chapter 12 -- The "carboNZero" program for mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions

- Chapter 13 -- The "Greening the Screen" program to foster green behavior

Given that agricultural products constitute over 50% of New Zealand's exports, and given that "within a 3.5-hour flight, Auckland has access to [only] 1% of world GDP and 0.4% of world population," it is reasonable to be concerned about the durability of food going to far away places. The concept of "food miles" yields a good and simple numerical indicator of the financial costs and environmental footprint (transportation, refrigeration) that may eventually render food exports unsustainable. The ensuing need for organizational adaptation is aptly illustrated by a case example about small winemakers embracing the need for carbon mitigation; it shows that much can be accomplished by endogenous organizational change even when exogenous forces remain adverse to carbon mitigation.

Landcare Research is a leader in the journey from unsustainability to sustainability. Leaders pay a price for being leaders, and they candidly report the problems they had in using the "triple bottom line" (TBL) method, which requires interdisciplinary analysis of the interdependencies between economic, social, and environmental factors. As anyone who has been through this knows, any diagram that attempts to show all the feedforward and feedback connections quickly starts looking like a plate of spaghetti and meat balls. It gets even denser as the perspective switches from local to national to global. Then the plate becomes so dense that it is impossible to distinguish the pasta from the meat. Transparency then becomes impossible even if it is desired, as discussed in the chapter on global perspective. For any given organization, transparency to the external world cannot be better than the internal transparency within the organization.

Chapter 10, entitled "Sustainability and Maori business," is one of the most interesting and instructive chapters of this book. The Maori business model is holistic and requires a long planning horizon. It is summarized in the book (Hatched, page 96) as follows:

|

Businesses lie at the heart of a progressive move by Maori to achieve

economic prosperity and self-determination (tino rangatiratanga), as well as

facilitating social equity, building human and cultural capital and protecting

and managing natural and cultural environments.

Maori business governance models have evolved from traditional to modern

forms, with many successful companies combining corporate capitalist

practice with strong cultural and environmental values and ethics. As such

Maori governance of businesses and organisations provide effective models

for sustainable business approaches globally.

However, these sustainable governance models are far more complex than

standard corporate models. Many Maori businesses face the challenge

of balancing financial imperatives with broader social, cultural and

environmental goals. A Maori business’s constituency (e.g. shareholders,

consumers) will rate its performance and define its success by

looking beyond profit margins and short-term planning. This has led many

Maori businesses and companies to develop long-term (often generational)

strategies and undertake sustainability reporting.

Maori culture remains unique forming a key element of Brand NZ which

is believed to be worth billions of dollars. It is critical that Maori branding

is protected and used with integrity to maintain its cultural and economic

value.

The Maori economy is emerging steadily within the wider New Zealand

economy. Maori organisations and businesses have made significant long-term

investments in human and financial capital. This investment, combined

with treaty settlements, will enable the Maori economy to play a significant

and growing role in New Zealand’s long-term prosperity. The long-term

and holistic focus that Maori businesses take reflect the spirit of sustainable

development:

"Manaaki Whenua, Manaaki Tangata, Haere whakamua"

"Care for the land, Care for the people, Go forward"

Wakatu Incorporation, Nelson, New Zealand

|

If they were not, the Maoris should have been invited by the United Nations to participate in the Brundtland Commission back in the 1980s. But there is evidence of Maori participation in the World Summit on Sustainable Development (Johannesburg, 2002), and this book shows that their input is important. It is important, because it supports the cultural reawakening that is urgently needed to overcome the impending demise of rigid capitalist and socialist models that no longer serve human progress going forward and, in fact, constitute an obstacle to a civilized transition from consumerism to sustainability.

That the Maori business model actually guides business practices is confirmed by the inclusion of cultural performance goals/indicators in Maori sustainability reporting as listed in Hatched, page 106:

Governance - cultural values are integrated across all levels in the business

Cultural practices - business retains, promotes, & advances cultural values, custom, practices, & activities

Economic - profits are used to advance and reinforce cultural values, social capital, social & cultural responsibility

Environmental sustainability - the business contributes to environmental & cultural protection/guardianship

Social - the business redistributes success and wealth back to the community, shareholders, stakeholders, & workers

Spiritual - the business has a soul & recognises a spiritual dimension and purpose above & beyond service, products, & profit

|

The Maori model does not exclude the adoption of Non-Maori "best practices" for guidance and/or certification. For instance, one of the listed indicators on performance for environmental sustainability is compliance with ISO-14001 (Environmental Management Systems - EMS) which is auditable. In fact, ISO-14001 is mentioned several times in the book. It is noted (in chapter 11 on life cycle management) that the Enviro-Mark EMS system meets all the requirements of ISO-14001. ISO-14065 (Verification of Validation of GHG Data) is also mentioned in connection with the carboNZero program (chapter 12). However, there are many other ISO standards and guidelines that are relevant to building capacity for sustainable development. The following are just a few examples:

ISO-9001 on Quality Management Systems - QMS, 2008

ISO-9004 on Managing for the Sustained Success of an Organization, 2009

ISO 14044 on Life Cycle Analysis for Environmental Management, 2006

ISO-15288 on the System/Software Life Cycle Process, 2008

ISO-31000 on Risk Management Guidelines, 2009

These standards contain valuable guidance for sustainable development and the preparation of sustainability reports and it is somewhat surprising that none of them are mentioned. Less surprisingly, since they are not yet published, the forthcoming ISO-26000 (Corporate Social Responsibility Guidance) and ISO-50001 (Energy Management Systems) are not mentioned either.

Even though the G3 Guidelines are generally invoked, there are still reservations about the veracity and completeness of corporate sustainability reports. Compliance with the guidelines is not auditable, and there is always the possibility that some corporations might issue fancy self-serving reports that are more marketing than substance. It would seem that Maori sustainability reports are trustworthy. But small businesses generally, and in particular small businesses in the developing nations, do not have the resources to publish good looking reports. A good wrapping is important, but even more important is compliance with auditable quality requirements, including verification and validation of data reported in publications. In this regard, ISO-9001 or some other equivalent certification is highly desirable to enhance the credibility of sustainability reporting.

Chapter 13, on Greening the Screen, is also of especial interest as it illustrates the use of TV and other media to foster awareness about the coming transition from consumerism to sustainability. Given the amount of TV violence and other junk that is pervasive in most of the developed nations, Greening the Screen is a program worthy of imitation.

Section 3, "Individuals as citizen consumers," develops the theme of sustainable consumption. There are five chapters in this section:

- Chapter 14 -- Consumption: categorization and motivators for mitigation/adaptation

- Chapter 15 -- What people buy as a signal of individual/group/national identity

- Chapter 16 -- Seeking pro-sustainability household behaviour change

- Chapter 17 -- Use of transformative communication to foster sustainability practices

- Chapter 18 -- Education for sustainability in secondary schools

Production and consumption are tightly coupled. As Victor Lebow pointed out back in 1955, "Our enormously productive economy… demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption… We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing rate." In other words, production requires consumption and vice versa. It follows that growing production requires growing consumption and vice versa. This mutually reinforcing feedback between production and consumption has led to a culture of consumerism that exacerbates the pressure created by population growth. Actually, global consumption per capita has been growing faster than the total world population.

As is well known, this is a global phenomenon by no means restricted to New Zealand. Section 3 starts with a summary that applies to both developed and developing countries (Hatched, page 133):

|

The choices people make – to consume certain products or live certain lifestyles –

can either sustain the environment or harm it. When we factor in the upstream and

downstream activities associated with these choices, our lifestyles account for the

majority of environmental impacts globally.

While the previous section, Business as sustainability innovators, focused on changing

production patterns, this section explores whether consumption patterns might

be changed. But to do so is a staggering task. So what knowledge and approaches

are needed to increase sustainable consumption? And what exactly is sustainable

consumption?

|

What is sustainable consumption? The answer provided in chapter 14 (Introduction to Sustainable Consumption) is the one formulated at the Soria Moria Symposium on Sustainable Consumption and Production, Oslo, 1994:

|

The use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and

bring a better quality of life while minimising the use of natural

resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste and pollutants

over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardise the needs of future

generations.

|

Chapter 14, authored by Helen Fitt and Sarah McLaren, is a very lucid explanation -- in plain English -- of sustainable consumption. There are more comprehensive publications about the topic, such as Gill Seyfang's excellent book, New Economics of Sustainable Consumption: Seeds of Change (Palgrave, 2009, 218 pages). But this chapter, in 10 pages, provides an excellent synopsis of the concept with supporting case examples. Starting with the Aristotelian basic categories of human desires,

- The desire for items required to meet basic human needs -- always good

- The desire for items that are not needed but satisfying without being harmful -- good with moderation

- The desire for items that are not needed and are harmful to human well-being -- always bad

the authors proceed to ask three key questions:

- Is consumption needed?

- Does consumption improve satisfaction with life?

- Does consumption cause harm>

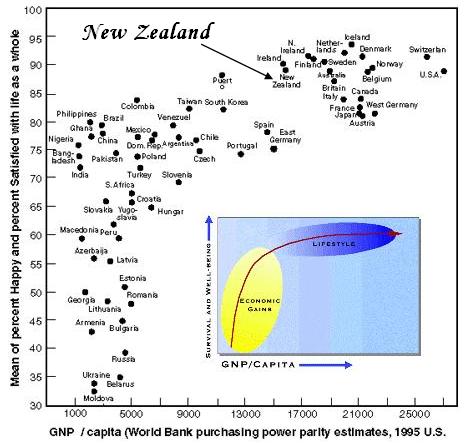

After noting that "ever-increasing wealth does not lead to ever-increasing happiness" (actually, we all know that too much of a good thing may become harmful) they provide the following evidence:

Sources: The country data is from World Bank's World Development Report 1997

The data is based on the World Values Survey 1981-2008

The inserted graphic conceptualization is by Ronald Inglehart, Princeton, 1997.

Bibliographic Citation: WORLD VALUES SURVEY 1981-2008 OFFICIAL AGGREGATE v.20090901, 2009.

World Values Survey Association. Aggregate File Producer: ASEP/JDS, Madrid, 2009.

Reprinted with permission of World Values Survey

The authors don't fail to notice that "residents of New Zealand report themselves as being happier than those of countries like Japan, France, and Canada despite considerably lower incomes." An interesting variation of this chart (not including New Zealand) can be found in Vision 2050, WBCSD, 2010, page 4. The same kind of curve is obtained by plotting GDP per capita and secondary education net enrolment (page 47).

Chapter 14 goes on to elaborate on consumption mitigation and adaptation options, and ways to motivate people to practice one or more of them. Chapters 15 to 18 build on chapter 14. The determinants of consumption behavior are analyzed at the individual (chapter 15) and household (chapter 16) levels. How to best foster sustainable consumption behavior by effective communications and secondary school education are the subjects of chapters 17 and 18. The following is a key insight that is generally applicable in all countries and cultures: "The least effective approaches were to induce regret or arouse fear. Guilt fails as an action motivator." (Hatched, page 163)

One alternative is to show what is to be gained. But how can the expected gains be shown if we are still uncertain as to what they are? Another alternative, one that is difficult but feasible here and now, is reformed education." The concluding remarks of chapter 18 (Hatched, page 184) are right on target: "No one is suggesting that change will be easy, but without it, today's youth, and tomorrow's decision-makers, will be underequipped to tackle the complex problems that a fast-changing world will throw at them."

Section 4, "Facing up to wicked problems," considers complex issues such as climate change. This is the longest section of the book, with nine chapters:

- Chapter 19 -- The so-called "wicked problems" and sustainability technologies

- Chapter 20 -- Looking at sustainability through a governance lens

- Chapter 21 -- Water allocation and the case example of Canterbury, NZ

- Chapter 22 -- Environmental management based on social learning

- Chapter 23 -- Evaluation of sustainability techniques

- Chapter 24 -- Fostering sustainability thinking via accounting practices

- Chapter 25 -- Stakeholder analysis

- Chapter 26 -- Supporting effective teamwork

- Chapter 27 -- Comparison of sustainable development approaches in NZ and Scotland

The summary page states (Hatched, page 185):

|

The complexity and value-laden nature of sustainable development as shown in the

previous sections provide examples of wicked problems. Creating solutions to these

require new modes of thinking and new ways of working. Here we reflect on some of

the theoretical insights and how these play out in practice. Much of this is in its infancy

and the pathways to maturity will take time and considerable effort.

|

Section 1 is about social problems that cannot be resolved by short-term fixes. Section 2 is about the socioeconomics of sustainable production, and Section 3 is about the socioeconomics of sustainable consumption. Section 4 is about approaches to actually resolve complex socioeconomic problems that require long-term solutions.

This is "where the rubber meets the road." Education (starting early at home, then primary school, then secondary school) is the best hope to avoid a crash landing. The following statement by Peter Senge (Tracing Connections, page 192),

"When education is driven by incessant pressures to perform on standardized tests, get good grades, get into the right college, with the goal of a good job and lots of money, then education reinforces the consumerism and economic orthodoxy that drive the present global business system. When education is oriented around deeper questions of human and social development, it can contribute substantially to the larger needs of a society needing desperately to reorient its priorities for a different future. In this sense, education is a natural leader in this time of 'great turning,' when the industrial age is dying and, as Vaclav Havel put it, 'something new, still indistinct, is struggling to be born.'"

|

is in perfect continuity with the concluding remarks of section 3 (chapter 18) and the initial remarks of section 4, as quoted above. The so-called "wicked problems" are typically interdisciplinary, long-term, and emerge under crisis conditions; and proposed solutions are seldom orthogonal to cultural values, entail significant uncertainty, and are likely to compound the crisis in the short-term. Section 4 provides an overview of the "state of the art" in tackling such problems.

A fundamental difficulty is that wicked problems are seldom amenable to deductive thinking. Deductive thinking is appropriate when there is a general theory about some phenomena that encompasses all possible variations. If the general theory can be mathematically formulated, then for any variation it is often possible to derive the model that applies to that variation. There is no such thing as a general theory of sustainable development, let alone a mathematical theory. Therefore, the researcher of sustainable development must often discard deductive reasoning and use inductive reasoning instead. In inductive reasoning the order of things is reversed: rather than deriving the specific case from the general theory, working hypotheses must be induced in an attempt to generalize from the specific case to more general situations that share some of the same structural and behavioral characteristics.

Chapter 19 describes three of these inductive approaches: Post-Normal Science (PNS), sustainability analysis techniques based on apprenticeship and experience, and futures studies. Any of these approaches requires interdisciplinary analysis, and interdisciplinary analysis requires specialized experts from the various relevant disciplines sitting around a table and trying to understand how the interaction of the disciplines contributes to the structure and behavior that emerges at their intersection. This kind of exercise usually requires good scenarios that all the experts can understand and agree upon, and a facilitator to ensure a collaborative atmosphere and prevent temper tantrums when one or more experts feel that their input is not being properly considered by the others.

Chapter 20 deals with governmentality, "a process to analyze the nature of institutions" and examine "how dominant values and worldviews influence policy development and implementation." Here in the USA, we need a lot of governmentality in connection with health care reform and other issues. This is a very important research area, as bad governance is one of the major obstacles to sustainable development in many countries. The free market cannot be counted upon to come up with solutions that strike a fair balance between individual freedom, private initiative, and the common good. Chapter 21 illustrates this with a case example pertaining to water allocation issues in Canterbury, New Zealand.

Chapter 22, by Margaret Kilvington and Will Allen, is most interesting. It discusses social learning as "a basis for practice in environmental management." The summary of the chapter is as follows:

|

Environmental agencies are increasingly being asked to formulate local, regional

and national responses to environmental problems that are highly complex, made

up of multiple factors, contested or unknown science, and conflicting demands.

Social learning is emerging as a useful framework for understanding the human

relationship, knowledge generation, and decision-making challenges posed by

complex environmental problems.

A social learning approach draws attention to five areas for focusing awareness

and developing practice in complex problem solving. These are:

1. How to improve the learning of individuals, groups and organisations

2. How to enable systems thinking and the integration of different information

3. How to work with and improve the social/institutional conditions for complex problem solving

4. How to work-manage group participation and interaction

5. The fifth factor is monitoring and evaluation, which is the engine that drives continuous improvement in practice.

The social learning framework offered here can be used to understand and

improve the capacity of any problem solving and management situation. It can

be used in its entirety or people may select elements of the framework for specific

phases of their projects.

|

The distinction between "single loop learning" (following the rules) and "double loop learning" (changing the rules) is worth noting -- see Hatched, page 222, box 5. There is also "triple loop learning" (learning about learning) that may lead not only to changing the rules but to changing the organizational structure that formulates the rules (quadruple loop learning). When changing organizational structure requires changing decision-making systems outside of the organization (suppliers, customers, government agencies, ....) then the plate of spaghetti and meat balls becomes so thick that it causes indigestion (quintuple loop learning).

Evaluating proposals for sustainability assurance is the subject of chapter 23. Sustainability appraisals require measurement in some scale. Actually, it requires measurements in 2, 3, or more orthogonal scales. Since visualization becomes difficult in more than three dimensions, here again is another area in which human brains require additional support. In New Zealand, sustainability appraisal is supported by the massive data base managed by Statistics New Zealand -- click on reference 1, page 237. This data base is instrumental for accounting for sustainability, which is the topic of chapter 24. Knowing what we are doing is not a sufficient condition for sustainability, but it is necessary.

Chapters 25 and 26 are on stakeholder analysis and supporting teamwork, respectively. "Stakeholder analysis is a way to identify a project's key stakeholders, assess their interests and needs, and clarify how these may affect the project's viability. From this analysis, programme managers can make plans for how these aspects will be addressed." This is goodness, because it approximates explicit consideration of the common good. The chapter mentions a "stakeholder analysis tool" -- basically, a matrix or mapping tool to categorize stakeholders and their needs and expectations (Figure 1, page 252). Chapter 26, on supporting effective teamwork, concedes that "while teams may be a necessary part of successful organizational change, their presence certainly doesn't guarantee success. As most people can testify [this reviewer included] groups can also be inefficient, confused, and frustrated. In fact, they can become little more a crutch unless they reconvene periodically for self-evaluation (a checklist is provided) and to update project plans as the nature of the work changes. Living projects need living documents, and living documents need living groups.

Chapter 27 is about "National Sustainable Development Strategies (NSDS)." Specifically, it is a comparison of the NSDS for New Zealand (the Sustainable Development Programme of Action (SDPOA), 2003) and the NSDS for Scotland (Choosing our Future (COF): Scotland’s sustainable development strategy, Scottish Executive, Edinburgh, 2005). It is a comparison of objectives and proposed courses of action; not a comparison of performance.

New Zealand's Sustainable Development Programme of Action (SDPOA)

In page 265 of Hatched, it is noted that ....

|

.... an OECD expert group commended New Zealand’s good practice in policy

integration in the SDPOA, which 'gives equal weight to social

sustainable development (in relation to the economy and

environment) with special attention to demographic trends,

new roles of women in society, improvements in health

and housing, and better integration of Maori communities'.

They also commended adoption of a broad indicator system

based on 40 indicators on the themes of population changes,

environmental and ecosystem resilience, economic growth and

innovation, skills and knowledge, living standards and health,

consumption and resource use, and social cohesion. The SDPOA

has not been replaced, since its conclusion in June 2006. A suite

of SD policy initiatives was announced in February 2007, but

these were overhauled after the 2008 General Election.

|

Choosing our Future (COF): Scotland’s sustainable development strategy

The COF is described in pages 268-269:

|

This strategy was developed under the umbrella of a shared UK framework

One Future – Different Paths which identified two outcomes

from pursuing SD: living within environmental limits and

ensuring a strong, healthy and just society. In addition,

three aspects that enabled these outcomes (achieving

a sustainable economy, promoting good governance

and using sound science responsibly) were part of the

framework. It is notable that the economy was not seen

as an end in itself, rather it was an enabler.

|

Both strategies anticipate a crucial role for the national governments. Both strategies envision a balance between economic growth and taking care of the human habitat. But, while the New Zealand strategy remains focused in New Zealand, the Scottish strategy (following the UK strategy) is more open to global issues. This is not an indication that New Zealanders are selfish and Scotts are more willing to take into account the global common good. It is an indication of how fast things are changing. The recent emergence (in terms of general awareness if not political will) of climate change as a global issue by now reflected in the latest NZ documentation, with "climate change" mentioned over 100 times in Hatched.

Chapter 27 concludes with a comparative analysis of the SDPOA and the COF. A quick comparison of these two NSDS with the NSDS that have been submitted by other countries reveals many variations but a convergence on the same fundamental paradox: how to reconcile economic growth with environmental sustainability. But a pattern seems to be emerging, albeit hesitatingly: the way to resolve the paradox is to make integral human development the top priority; and the way to achieve the paradigm shift is not by exacerbating guilt and fears about the future but by showing that having less, and being more, is the authentic path toward growth in human satisfaction and well-being.

Section 5, "The future as a set of choices," is about the critical issue of balancing individual self-determination and the common good at all levels -- locally, nationally, and globally. The two chapters in this section are about the need for mutual support between business and science (chapter 28) and proposals for further research on New Zealand's sustainable development (Chapter 29).

There is another paradox that must be resolved. As Amartya Sen has pointed out very convincingly, sustainable human/social development requires self-determination and autonomy to allow people to take initiatives on their own - provided they are compatible with the common good - rather than the "elites" telling them what is good for them. Thus envisioning "the future as a set of choices" is right on target. But, at the same time, it is recognized that government bodies will need to have a more pro-active role, at least by way of applying "sanity checks" to the so-called "free markets" -- which are free for the wealthy elites but not for vast majority of people, especially the poor and very poor. Just as refocusing on human development is the way to resolve the pocketbook/planetbook paradox, growth in the capability for practicing the principles of solidarity and subsidiarity is the way to resolve the self-interest/common-interest paradox.

In this perspective, sustainable development is really an unending collaborative process (Hatched, pages 297-302). It is unending, because sustainable development issues are both complex and evolving, with new questions bound to arise as progress is made, or "where a question resolutely defies answering, a better quality question is needed." It is collaborative, because making progress requires both technical collaboration and "collective leadership across organizations, communities, and national boundaries" -- in fact, the requirements for global citizenship and collective leadership at the global level are becoming increasingly apparent. It is a process, because sustainable development theory and practice is about understanding and working out interdependencies that are not static but dynamic; in other words, the interdependencies change as the sustainable development process unfolds. Therefore, building capacity for sustainable development must include continuous improvement in the capability to resolve these interdependencies -- and keep resolving them as they change.

The authors of this insightful epilogue are the three senior editors of the book, and they conclude as follows (page 301):

|

New Zealand’s capability for sustainable development has most

certainly hatched. What will now be the wind on which it takes

flight? Will it be the values of a South Pacific nation? Will it be a

greater profit margin and market share for those that develop

new products, services and business models? Or will it be new

forms of collaboration across society that transcend national

and business boundaries?

The world is a small place and New Zealand will not be immune

from the impacts that climate change, poverty or resource

depletion have on other nations. When our indicators of

social, environmental, economic and cultural capital are all

increasing, we will say we are making progress. When we see

less deprivation and greater security nationally and globally, we

will say we are making a difference.

|

4. Capacity for Sustainable Development in Developed Nations

The following UN Agenda 21 references provide basic guidance on building capacity for sustainable development in a country and sharing it with other countries:

United Nations Agenda 21, UN, 2002

Guidance in Preparing a National Sustainable Development Strategy - Managing Sustainable Development in the New Millennium, UN, 2002

United Nations Agenda 21 Documents, UN, 2002

Transfer of Environmentally Sound Technology, Cooperation & Capacity-Building, UN, 2002

National Mechanisms & International Cooperation for Capacity-Building in Developing Countries, UN, 2002

Hatched certainly complies with the Agenda 21 guidance, which applies to all countries. The "futures literacy" emphasis, which is not required by the Agenda 21 model, presupposes language literacy and socioeconomic conditions that allow for long-term planning. In this regard, Hatched would seem to be more applicable to developed countries. So is the need for dialogue between business and culture when human capital and other resources make this possible. There is a lot more the developed nations could be doing in this regard.

Awareness is increasing about the need for dialogue between culture and all dimensions of human knowledge and activity. But the notion of a for-profit business that recognizes, supports, and contributes to the world of culture would still be news for most entrepreneurs in the industrialized nations. In the business world, not even the "triple bottom line" model is so holistic. For the "triple bottom line" takes into account the economic, social, and environmental impacts of business activity; and culture includes all three of these but also transcends them to include spirituality and moral values. This is critically important because the interaction between business and culture should not be restricted to a mere repetition of old practices. While being sensitive to cultural values and realities, business activity should include an active involvement in keeping traditions alive and growing in wisdom and benefit to humanity, by the continuing integration of human learning and experience, generation after generation.

Furthermore, there are software tools now available that can be helpful in understanding and managing interdependencies among sustainable development issues. It should be stressed that none of these tools provide "solutions" to anything. They do, however, support collaborative futures research and long term planning by providing tracking and visualization of interdependencies as the sustainable development process unfolds. For instance, software tools such as the Problem Solving Matrix (PSM) and Explainer Engine and Structural Thinking Experiential Learning Laboratory with Animation (STELLA) (see also Tracing Connections) can be helpful if properly used.

Needless to say, these tools are readily available in the developed countries, but not so readily available in the developing countries.

The Landcare Research sustainability web site is rich in content and includes their GRI-compliant sustainability reports and databases. The book, and the web site, would be even more useful if they were to provide a state-of-the-art survey of "decision-support" tools capable of tracking changes in complex interdependencies. There are many such tools, but using any of them properly requires training. See, for example, Integrative models for sustainable development, European Commission - Research, 2010, and Decision-support tools and the indigenous paradigm, by T. K. K. B. Morgan, Proceedings of the ICE - Engineering Sustainability, Volume 159, Issue 4, pages 169–77, 2006.

Are the book contents useful for other developed countries?

They certainly are. The mitigation and adaptation options offered by Hatched are not intrinsically different than those available to other developed countries. Mitigation options such as carboNZero and adaptation options such as the explicit consideration of the cultural dimension as the fourth pillar of sustainable development -- in addition to the social, economic, and environmental dimensions -- are worthy of imitation. It is noted that New Zealand's "fourth pillar" derives from the Treaty of Waitangi (1840). There are still differences of opinion on the meaning of the treaty's text regarding other issues, but it is clear that the Maori culture must be integrated with European and other cultural legacies when making decisions for the national common good. So is the case in all countries with multiple cultures.

5. Capacity for Sustainable Development in Developing Nations

There are several ways in which the contents of this book can be useful to analyze and manage sustainable development in the developing nations, including those afflicted by pervasive poverty. The book is candid about mistakes that have been made in New Zealand (and most other industrialized nations) and need not be repeated in other countries. Some years ago, many developing nations wanted to have a petrochemical in order to spark economic development. Hopefully the misconception that every country needs a petrochemical is by now mercifully overcome, but other misconceptions remain. A case in point is the management of innovation for sustainable development. In the Hatched e-book, the reader can get 46 examples of "do's and don'ts" by searching for "innovation."

Chapter 10, on the Maori business model, is an outstanding example of how the book can be useful in developing countries. The progress of any country toward sustainable development is compromised if indigenous cultures and business practices are disregarded. For indigenous practices that were never contaminated by the industrial revolution are often amazingly wise when it comes to sustainability. Indigenous "accounting systems" seldom (never?) treat environmental impacts as "externalities" that need not be included in the cost of using natural resources. Indigenous people know (without needing to take courses in sustainability) that unsustainable development is an oxymoron -- the well known case of removing trees from the Amazonian rainforest to use the land for commercial forestry and agriculture comes to mind.

Another interesting exercise is to search the Hatched e-book for "initiative." This search returns 93 hits. The reader is invited to replicate the search and take a quick look at the 93 places in the e-book where the term "initiative" is used. Some of the hits are in a context that is specific to New Zealand. But most of the hits relate to issues that emerge during sustainable development in any country -- whether already developed by current standards or at various stages of development. For instance, initiatives related to:

- The lack of adequate and sustained funding for long-term planning (page 9)

- The need for a baseline of national and local planning scenarios (page 37)

- Responsiveness to the Global Reporting Initiative (pages 57, 83)

- Communication issues with the news media (page 89)

- Fostering participation by indigenous and all cultural groups (page 99)

- Setting priorities based on intergenerational human capital accumulation (page 103)

- Use of environmental management systems such as ISO-14001 (page 104)

- Integrated product policies and life cycle management (page 113)

- Pro-active global marketing of the country's products (page 131)

- Effective ways to promote sustainable production programs/technologies (137)

- Effective ways to promote consumption mitigation/adaptation options (pages 144-154)

- Innovative methods to facilitate education for sustainability (pages 157-182)

- Extended peer communities to foster participation by all interested citizens (page 192)

- Formulation and implementation of best practices in pest management (page 220)

- How to get local/city councils involved in the process (page 242)

- Stakeholder analysis to ensure identification of all stakeholders (page 251ff)

- Articulation of sustainability policies for consideration by elected officials (page 265)

- Dispelling the myth that "you cannot be green when you are in the red" (page 289)

- Political and technical ways of supporting collaborative leadership (pages 292-300)

- Coordination of initiatives by local/central governments, NGOs, other groups (page 302)

All the above are universal to sustainable development, and the manner of their manifestation in developed versus developing nations is more a matter of degree than a matter of substance, even though local cultural attachments -- and sometimes the vexing realities of religious fanaticism -- may obscure the underlying similarities.

Relative to long-term planning/futures research and the use of state-of-the-art decision-support tools, it is often the case that Third World countries simply don't have the resources to use them. And yet, the webs of interdependencies created by globalization make using them is as critical for developing nations as it is for developed nations. In this regard, distributive justice should include sharing of the human and technological capital of those who have it with those who don't. This is a sensitive matter, as the sharing can be neither imposed nor presumptuous. Developing nations should wake up to the need of requesting such assistance, which is more important than financial aid. Developed nations should be ready to provide a response that is politically and culturally sensitive; and, the governments of developed nations should be ready to provide appropriate funding to support groups and institutions willing to embark in "missionary work of the 21st century." Such missionary work will not have anything to do with conquering land or imposing cultural values. It will have everything to do with contributing brains and technologies in ways that facilitate acceptance and adaptation by the nations requesting assistance. A country that can produce Hatched can do this kind of missionary work. This is the splendid challenge looming ahead for nations like New Zealand.

Are the book contents useful for developing countries?

The high priority given to futures research might seem to be counter indicated for developing countries. But even the poorest countries must build for the future. And why should they have to repeat the same mistakes that the now developed countries have made? This book exemplifies, and appropriates for New Zealand, Amartya Sen's model of capacity building for sustainable development. Sen's model is basically one in which capacity increases in proportion to the degree of freedom (autonomy, freedom of choice, self-determination) granted to individuals and local communities. Sen's model is rooted in human nature (homo sapiens sapiens) and has universal applicability as a general strategy for sustainable development, even though individual and local manifestations of applying the model always needs tailoring to local conditions, resources, and cultures. Hatched offers almost as much universality and almost as much tailorability. In fact, recognition of local autonomy for making local decisions is fully in accord with the universally applicable principle of subsidiarity. The developing nations should avoid the kind of centralization of power that suffocates local initiatives.

6. Limited Coverage of Distributive Justice and Gender Equality Issues

There is a very limited coverage of transnational distributive justice and gender equality issues.

As Helmut Lubbers has suggested, it seems reasonable to "support development in geographical areas that lack basic standards of living. Such development must be compensated by equivalent reduction of luxuries in the overdeveloped areas." It would seem that this is what distributive justice requires. Easier said that done of course, but it is unfortunate that the issue of distributive justice is mentioned in the book (pages 189, 212, 230) only in the context of vested interests and intergenerational equity within New Zealand. It is never mentioned in the context of the global geography of poverty and other transnational inequities.

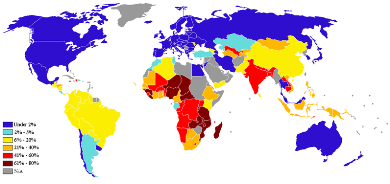

Global Geography of Poverty

Sources: UN Human Development Statistics, 2008, and Demographics of Poverty, Wikipedia, 2010.

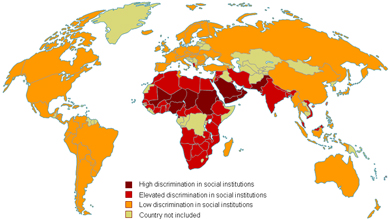

The issue of gender equality, critical as it is in so many regions of the world, is not mentioned as a crucial precondition for sustainable development. The contributions of women to social life and human wellbeing are mentioned a few times (pages 45, 156, 162, 252, 265) but only in passing. Perhaps this is not an issue in New Zealand. In the 2009 Global Gender Gap Report, which ranks national progress in closing the gender gap, New Zealand ranks 5th among 134 nations. Not bad .... And, the OECD database on gender equality in social institutions shows New Zealand among the countries where gender discrimination is low:

Global Geography of Gender Equality

Source: Global Geography Gender Equality in Social Institutions, OECD, 2009.

Again, New Zealanders should count their blessings. However, in the interconnected world of the 21st century, the fact that they are better off than most does not exonerate them from the responsibility to share their experience and resources with those who are not so fortunate. Ethics, and solidarity with the human race, hopefully will prevent New Zealanders from staying in the comfort of their beautiful islands while billions suffer hunger and misery. The 8th Millennium Development Goal is to attain "a global partnership for sustainable development." At the moment, lack of political will is the biggest obstacle to make further progress. Perhaps New Zealand can afford to assume a role of leadership in this regard?

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion

This book is a significant contribution to sustainable development in both developed and developing nations. Even though it is based on the New Zealand experience, most of the material should be of interest to sustainable development professionals everywhere. The book covers the social, economic, environmental, and cultural dimensions of the sustainable development process. Tailoring the Hatched capacity building model for other countries would require case examples that fit the social, economic, environmental, and cultural realities of each country. A more explicit elaboration of distributive justice and gender equality issues would be indicated for most countries. Also desirable would be restating sustainability and sustainable development concepts (and case examples) in terms that include social maturity factors such as practicing the principles of solidarity and subsidiarity. Otherwise, the learning concepts and sustainable development practices documented in Hatched are universally relevant.

Recommendations

Nothing human is perfect or definitive, and this is surely the case for a book about sustainable development -- which is "unending." The following are offered as suggestions (in no particular order of importance) that the Hatched team may want to consider in order to carry this work forward.

- On the issue of distributive justice

Distributive justice transcends economic wealth. Human and social capital are also unevenly distributed throughout the world, and surely this is not so because a few nations have been endowed with "superior" people. The reasons for geographic differences in human development are too complex to be discussed here, but it would be well for nations that have "hatched" high levels of education and intellectual capacity to encourage their birds to fly beyond their own borders; for birds that do not fly are not much better than eggs that do not hatch. Researching ways for New Zealand to "export" capacity for sustainable development would be a most valuable undertaking, and the team that wrote this book could take the lead.

- On the issue of gender equality

See, for example, Power, Voice and Rights: A Turning Point for Gender Equality in Asia and the Pacific, UNDP Asia-Pacific Human Development Report, February 2010. Granted that cultural differences are a factor, New Zealand should "export" awareness of the benefits derived from gender equality. Finding appropriate ways to do this would be another valuable follow-up to the research project that culminated with this book.

- On the integration of sustainability principles with closely related principles such as solidarity and subsidiarity

Building capacity for sustainable development requires building capacity for a transition for competition to collaboration. This in turn requires a transition from "dog eats dog" competition to social solidarity and political subsidiarity. Solidarity entails a culture in which decisions made for self-interest alone are not "politically correct." Decisions must be made with both self-interest and the common good in

mind. The principle of subsidiarity, whereby authority and responsibility are delegated to the lowest level consistent with the common good, is a key enabler of solidarity. See, e.g., the European Union Sustainable Development Strategy (EU SDS).

On the use of ISO-9001 and other quality standards

In the era of globalization, the ISO standards may offer the best way to establish confidence in the quality of goods and services that travel via the worldwide trade web. Countries that export junk will find that the pain of having their products rejected by consumers in importing countries is much greater than the minor inconvenience of getting their products certified -- assuming the certification and audit process is not corrupted. This is not a case of either win/win or win/lose. It is a case of "no pain, no gain."

On researching a formal foresight process for long-term planning .... consider, for example:

On the use of analytical decision-support tools .... consider, for example:

- Matrix analysis tools for understanding interdependencies, such as the Problem Solving Matrix (PSM) and Explainer Engine (conceptually simple but requires facilitation).

- Simulation tools for understanding complex system behavior over time, such as STELLA and the recently published Tracing Connections (kind of a "second wave" of the MIT System Dynamics method).

- NB: These tools do not solve any problems, but do support decision-making in collaborative settings.

On updating the official New Zealand National Sustainable Development Strategy (NZ NSDS)