“I came to the ocean to heal, but found an ocean that needed healing.” That was the realization that inspired artist Angela Haseltine Pozzi to dedicate her life to saving the sea. Her medium? Trash.

When Pozzi suddenly lost her husband, she took time to look for something meaningful and constant. Her search led her back to the Oregon shores of her childhood. There, she expected to find the familiarity and predictability of crashing waves. Instead, her life found new meaning and change.

As Pozzi walked along the Pacific shores, she found piece after piece of plastic littering the sand. Passers-by collected shells nearby, leaving the pieces of trash untouched. At that moment, Pozzi decided that the problem of ocean pollution could not be left ignored. She had been an art teacher—she knew how to motivate and educate. She decided to develop the Washed Ashore project to show that the plastic problem was real.

She could have raised awareness by brandishing photos of dead sea birds or of beached whales —their stomachs filled with plastic debris. Instead, she used her experience making art from odd bits and pieces (“As a teacher,” she says, “you learn to work with a small budget.”). She channeled what she had learned from her father, a museum director, and her mother, an artist, to create an experiential project that would eventually reach thousands.

From Trash to Art

Washed Ashore is a massive undertaking. Pozzi works with a team of only nine people. Over the year, over ten thousand independent volunteers collect scraps of trash along 160 kilometers (100 miles) of the Oregon coast. For beachgoers, Pozzi has given the process of picking up trash a new value and purpose. Already, volunteers have gathered and sorted 18 tons of garbage (equivalent to the weight of more than three elephants) since the project began in 2010. The Washed Ashore program uses about 95 percent of the waste that is collected to create eye-catching, larger-than-life sculptures of marine life.

Pozzi’s aim is to create a “heart connection” with the issue. She moves this difficult discussion away from guilt and distress and toward ownership and beauty. After Pozzi and a team of high school welding students create the framework for the pieces, volunteers create sections of “skin” by hand with the salvaged plastic and build an emotional connection to the animal they have helped create. Once the pieces are completed, viewers can touch the works, often finding every-day objects like toothbrushes and plastic toys.

What’s the Plastic Problem?

Ninety percent of the trash that gets collected on the beaches by the Washed Ashore volunteers is petroleum-based: nets, nylon ropes, and plastic items. That’s not surprising, given that approximately 10–20 million tons of plastic end up in the oceans each year.

Thirteen billion dollars a year is lost as a result of the environmental damage that plastics bring to marine ecosystems, including financial losses by fisheries and tourism as well as time spent cleaning beaches. A recent study conservatively estimated that 5.25 trillion plastic particles are currently floating in the world’s oceans. Because plastics are moved with wind and currents, very few areas in the ocean may have escaped plastic pollution. The North Pacific gyre contains the most, with nearly 2 trillion pieces of plastic (weighing over 96,000 tons).

All of this ocean plastic has massive consequences on marine life. Animals such as seabirds, whales, and dolphins can swallow or become entangled in plastics. Floating plastics—such as discarded nets, docks, and boats—transport microbes, algae, invertebrates, and fish into non-native regions. That’s why Washed Ashore’s creations are often inspired by the ocean animals that are most affected by plastic.

How Did This Problem Begin?

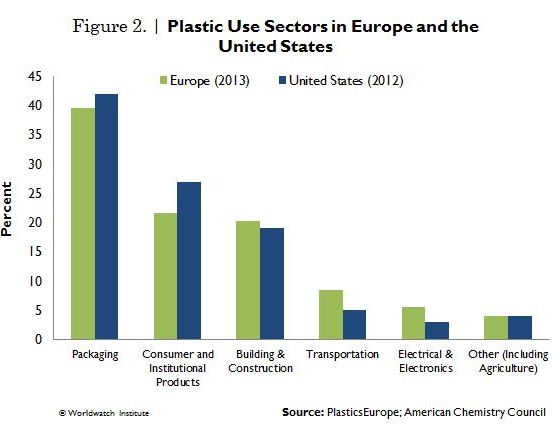

Plastic production became one of the fastest growing industries in the 1940s. In 2013 alone, some 299 million tons of plastics were produced. An average person living in Western Europe or North America consumes 100 kilograms (220 pounds) of plastic each year, mostly in the form of packaging. Asia currently uses just 20 kg (44 pounds) per person, but this figure is expected to grow rapidly. Because most plastic is used just to package the products we use, it is thrown away soon after an item’s purchase. Consumers continue to fuel the demand for plastic and its promise of convenience and low cost. However, there is limited attention to the wider impacts of most purchases.

See the full Vital Signs report here.

The plastic problem is systemic. Each year, millions of tons of plastics are produced. In Europe, only 26 percent (about 6.5 million tons) of discarded plastic was recycled in 2012 (an additional 36 percent was incinerated for energy recovery). In the United States, only 9 percent (2.8 million tons) of the plastic that Americans discarded was recycled in 2013. The rest was sent to landfill or made its way into the natural environment.

A Vision for the Future

“Marine debris is not the problem, it is a symptom of the problem” says Pozzi. “All of this ocean debris was once purchased. Somebody made the choice to buy it.”

Pozzi’s work ultimately forces us to stop and think. Her pieces move us from wonder to awareness, opening the conversation with arresting works. In her art, we see the toothbrush we unceremoniously threw out. We see the empty bottle of ketchup that was never recycled. Plastic never goes away. That fact is made palpably clear.

“We need more than ‘reduce, re-use, recycle,’” says Pozzi. “We must also rethink, repurpose, find alternatives, and take action. We need to stop and think.”

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gaelle Gourmelon is the Communications Director at the Worldwatch Institute. She has a background in biology and environmental health and focuses on how we can use social institutions and the planet’s resources more effectively.

|