|

ARTICLES

Editorial Essay: Climate Change or Cultural Change?

Socially Constructed Silence? Protecting Policymakers from the Unthinkable, by Paul Hoggett and Rosemary Randall

Art Transforms Plastic Pollution: Washed Ashore, by

Gaelle Gourmelon

A Biopsy on an Economy, by Jeffery J. Smith

Understanding, Tolerance, and Systems of Logic, by Carmine Gorga

Globalization and the American Dream, by Helena Norberg-Hodge and Steven Gorelick

Why the P2P and Commons Movement Must Act Trans-Locally and Trans-Nationally, by Michel Bauwens

Revealing Nature's Vulnerabilities As Our Own, by Lisa Lebofsky

Voluntary Family Planning to Minimize and Mitigate Climate Change, by John Guillebaud

An Expanded Realm of Desire, by Elisabetta Corrà

The SDGs in Latin America and the Caribbean, by Susan Nicolai, Tanvi Bhatkal, Christopher Hoy, and Thomas Aedy

I Assumed It Was Racism—It Was Patriarchy, by

Akiba Solomon

SUPPLEMENTS

Advances in Sustainable Development

Directory of Sustainable Development Resources

Strategies for Solidarity and Sustainability

Best Practices for Solidarity and Sustainability

Fostering Gender Balance in Society

Fostering Gender Balance in Religion

Meditations on Man and Woman, Humanity and Nature

Climate Change or Cultural Change?

The term "climate change" has become a surrogate for "ecological crisis." It is worrisome to see billions of dollars being spent in "fighting" climate changes, real or imaginary, that may be due to natural variations, or human activities, or some combination of both. What is undeniable is that the biosphere is being trashed by a growing population and excessive consumption, and these are both the direct consequence of human decisions and actions. In any case, it is also undeniable that significant human adaptation will be required as climate changes and all manner of pollution and toxic substances contaminate the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we breathe. A bold cultural revolution is needed to face newly emerging global realities of ecological degradation, resource depletion, and massive migrations of people escaping from poverty and/or violence. Climate change mitigation measures and better weather services are certainly needed, but what is needed the most is human adaptation enabled by cultural change pursuant to integral human development, whereas distractions motivated by ideologies or profiteering have marginal or negative value.

Every global citizen can and must do something to self-adapt and help others adapt. However, it is irrational to expect that people, acting spontaneously, can resolve the ecological crisis, let alone get ready for climate change. Poor people do not have the resources to do much, busy as they are subsisting on a few dollars a day. Middle class people are too busy working, many trying to work and study at the same time, or running around from one job to another as they become seduced by marketing campaigns to spend more and more, to consume more and more, for the economy to "grow" more and more. Rich people do what rich people naturally do, keeping busy in good jobs that pay well to continue enjoying their comfortable lifestyle, and investing in financial instruments that enhance their bank accounts at the expense of poor and middle class people that keep borrowing in their attempt to climb the ladder. So the borrowing and spending spiral keeps going up, environmental quality keeps going down, and human institutions keep "fiddling while Rome burns."

Most institutions in our current human civilization are in desperate need of reform, and this applies to both secular and religious institutions worldwide. The reason is that, since the onset of the agricultural revolution, human relations, and all kinds of human initiatives, have become vitiated by the patriarchal paradigm of male domination and female subordination, also manifested as human domination and nature subordination. The industrial revolution enhanced the human capacity for exploiting nature, and the information revolution is further exacerbating debt-based marketing and the production-consumption growth frenzy. Irresponsible population growth is part of the problem; but irresponsible political and financial institutions are a major part of the problem, and religious institutions that perpetuate the patriarchal mindset via images of an omnipotent male God are an even greater part of the problem. Institutional problems require institutional solutions. Climate change may be real but let it not become a convenient distraction; what we really need is cultural change, from patriarchy to solidarity and sustainability.

Socially Constructed Silence?

Protecting Policymakers from the Unthinkable

Paul Hoggett and Rosemary Randall

This article was originally published in

Transformation, June 2016

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

The scientific community is profoundly uncomfortable with the storm of political controversy that climate research is attracting. What’s going on?

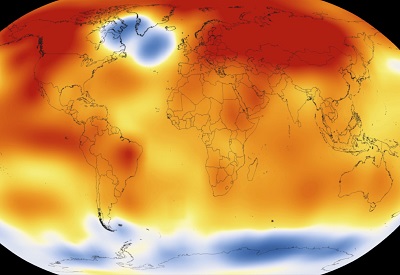

Credit: By NASA Scientific Visualization Studio/Goddard

Space Flight Center.

Public Domain, Wikimedia.

Some things can’t be

said easily in polite company. They cause offence or stir up intense

anxiety. Where one might expect a conversation, what actually occurs is what

the sociologist Eviator Zerubavel calls a ‘socially

constructed silence.’

In his book Don’t Even Think

About It, George Marshall argues that after the

fiasco of COP 15 at Copenhagen

and ‘Climategate’—when

certain sections of the press claimed (wrongly as it turned out) that leaked

emails of researchers at the University of East Anglia showed that data had

been manipulated—climate change became a taboo subject among most politicians,

another socially constructed silence with disastrous implications for the

future of climate action.

In 2013-14 we carried

out interviews

with leading UK climate scientists and communicators to explore how they

managed the ethical and emotional challenges of their work. While the shadow of

Climategate still hung over the scientific community, our analysis drew us to

the conclusion that the silence Marshall spoke about went deeper than a

reaction to these specific events.

Instead, a picture

emerged of a community which still identified strongly with an idealised

picture of scientific rationality, in which the job of scientists is to get on

with their research quietly and dispassionately. As a consequence, this

community is profoundly uncomfortable with the storm of political controversy

that climate research is now attracting.

The scientists we spoke

to were among a minority who had become engaged with policy makers, the media

and the general public about their work. A number of them described how other

colleagues would bury themselves in the excitement and rewards of research,

denying that they had any responsibility beyond developing models or crunching

the numbers. As one researcher put it, “so many scientists just want to do

their research and as soon as it has some relevance, or policy implications, or

a journalist is interested in their research, they are uncomfortable.”

We began to see how for

many researchers, this idealised picture of scientific practice might also offer

protection at an unconscious level from the emotional turbulence aroused by the

politicisation

of climate change.

In her classic study of

the ‘stiff upper lip’ culture of nursing in the UK in the 1950s, the

psychoanalyst and social researcher Isobel Menzies Lyth developed the idea of ‘social defences

against anxiety,’ and it seems very relevant here. A social defence

is an organised but unconscious way of managing the anxieties that are inherent

in certain occupational roles. For example, the practice of what was then called

the ‘task list’ system fragmented nursing into a number of routines, each one

executed by a different person—hence the ‘bed pan nurse’, the ‘catheter nurse’

and so on.

Ostensibly, this was

done to generate maximum efficiency, but it also protected nurses from the

emotions that were aroused by any real human involvement with patients, including

anxiety, something that was deemed unprofessional by the nursing culture of the

time. Like climate scientists, nurses were meant to be objective and

dispassionate. But this idealised notion of the professional nurse led to the impoverishment

of patient care, and meant that the most emotionally mature nurses were the

least likely to complete their training.

While it’s clear that

social defences such as hyper-rationality and specialisation enable climate

scientists to get on with their work relatively undisturbed by public anxieties,

this approach also generates important problems. There’s a danger that these

defences eventually break down and anxiety re-emerges, leaving individuals not

only defenceless but with the additional burden of shame and personal

inadequacy for not maintaining that stiff upper lip. Stress and burnout may

then follow.

Although no systematic

research has been undertaken in this area, there is anecdotal evidence of such burnout

in a number of magazine articles like those by Madeleine Thomas and Faith Kearns,

in which climate scientists speak out about the distress that they or others

have experienced, their depression at their findings, and their dismay at the

lack of public and policy response.

Even if social defences

are successful and anxiety is mitigated, this very success can have unintended

consequences. By treating scientific findings as abstracted knowledge without

any personal meaning, climate researchers have been slow to take responsibility

for their own carbon footprints, thus running the risk of being exposed for

hypocrisy by the denialist lobby. One research leader candidly reflected on

this failure: “Oh yeah and the other thing [that’s] very, very important I

think is that we ought to change the way we do research so we’re sustainable in

the research environment, which we’re not now because we fly everywhere for

conferences and things.”

The same defences also

contribute to the resistance of most climate scientists to participation in

public engagement or intervention in the policy arena, leaving these tasks to a

minority who are attacked by the

media and even by their own colleagues. One of our interviewees who has

played a major role in such engagement recalled being criticised by colleagues

for “prostituting science” by exaggerating results in order to make them “look

sexy.”“You know we’re all on the same side,” she continued, “why are we

shooting arrows at each other, it is ridiculous.”

The social defences of

logic, reason and careful debate were of little use to the scientific community

in these cases, and their failure probably contributed to internal conflicts

and disagreements when anxiety could no longer be contained—so they found

expression in bitter arguments instead. This in turn makes those that do engage with the public sphere excessively

cautious, which encourages collusion with policy makers who are reluctant to

embrace the radical changes that are needed.

As one scientist put it

when discussing the goal agreed at the Paris climate conference of limiting

global warming to no more than 2°C: “There is a mentality in [the] group that

speaks to policy makers that there are some taboo topics that you cannot talk

about. For instance the two degree target on climate change...Well the

emissions are going up like this (the scientist points upwards at a 45 degree

angle), so two degrees at the moment seems completely unrealistic. But you’re

not allowed to say this.”

Worse still, the

minority of scientists who are

tempted to break the silence on climate change run the risk of being seen as

whistleblowers by their colleagues. Another research leader suggested that—in private—some

of the most senior figures in the field believe that the world is heading for a

rise in temperature closer to six degrees than two.

“So repeatedly I’ve heard

from researchers, academics, senior policy makers, government chief scientists,

[that] they can’t say these things publicly,” he told us, “I’m sort of

deafened, deafened by the silence of most people who work in the area that we

work in, in that they will not criticise when there are often evidently very

political assumptions that underpin some of the analysis that comes out.”

It seems that the idea

of a ‘socially constructed silence’ may well apply to crucial aspects of the

interface between climate scientists and policy makers. If this is the case

then the implications are very serious. Despite the hope that COP 21 has

generated, many people are still sceptical about whether the rhetoric of Paris

will be translated into effective action.

If climate change work is

stuck at the level of ‘symbolic policy

making’—a set of practices designed to make it look as though

political elites are doing something while actually doing nothing—then it

becomes all the more important for the scientific community to find ways of

abandoning the social defences we’ve described and speak out as a whole, rather

than leaving the task to a beleaguered and much-criticised minority.

|