One of the promises of unregulated extreme capitalism is that problems of supply and demand will always “work themselves out” in an unregulated market, and hence that any market regulation will necessarily make things worse.

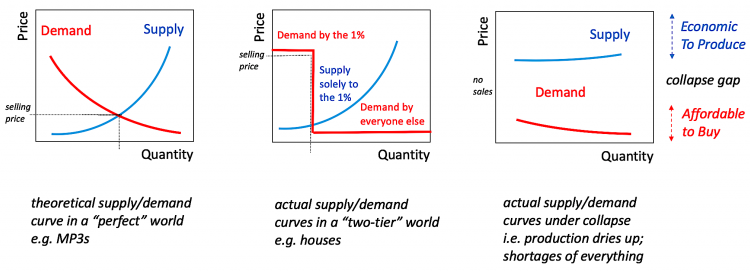

The idea is that where the supply curve (how much sellers are willing to sell at various prices, a curve with a positive slope) intersects the demand curve (how much buyers are willing to buy at various price points, a curve with a negative slope), determines how much of each commodity will be sold (how far along the x axis the supply/demand intersection is), and at what average price (how high up the y axis the intersection is). (See left-most chart below.)

Analysis of supply and demand curves ~ Click the image to enlarge

This utopian presumption of course assumes an equitable distribution of wealth (which determines demand) and an unlimited access to resources (which determines supply). When you have a grossly inequitable distribution of wealth, you end up with a high demand for multi-million dollar mansions and extravagant sports cars (billionaires with nothing better to do with their excess wealth), and a low ‘demand’ for the necessities of life because most people can’t afford to buy them.

Likewise, when you have serious resource and supply constraints, you end up with no supply, at any price, or, worse, you end up supplying only those willing and able to pay an insane price (by most people’s standards) for the scarce resource, and everyone else doing without. (See middle chart above.)

And, in the worst case scenario, when you have both inequitable distribution of wealth and serious resource and supply constraints, you end up with a market collapse — the maximum price buyers can afford to pay is lower than the minimum price sellers can afford to charge without losing money, so sellers stop producing new supplies (that they can’t sell) and buyers run out of everything. (See right-most chart above.)

This will soon become a permanent problem in the energy sector, as increasing extraction costs, despite massive subsidies, mean that producers need to earn at least $50/bbl to stay in business, and that amount is rising, while consumers can only afford to pay at most $80/bbl to remain solvent, and that amount is falling (as real disposable income for all but the richest continues its 50-year slide). Current bottlenecks in many areas have driven oil prices up to $85/bbl, twice what they were a year ago, which means the coming winter (which is expected to be unusually cold in much of North America) is going to be brutal for many. Natural gas has undergone a similar doubling of price in the last year, partly due to shortages caused by the uneconomically low prices a year ago leading to layoffs and production cuts. This whipsawing is likely to continue.

We’re seeing a bit of an advance look at this these days in what is being called a “supply chain” crisis, much as we did during the economic crisis and collapse of 2008. For a host of reasons largely resulting from the pandemic, supplies of all kinds of goods have been disrupted. The previous drop in demand has meant that suppliers laid people off and reduced inventories, and imports and exports slowed. The laid off workers had less money to spend, reducing demand further. And as hiring then increased and more emergency money was given to citizens to help them deal with the loss of employment, there was a sudden jump in consumer demand that could not be met by the reduced workforce with the lower levels of shipping.

Suddenly, shipping containers are piling up in some places and completely unavailable in others. Employers paying inadequate wages for the risk and stress of the work, a situation exacerbated by the pandemic, find themselves without necessary workers, and many transport vehicles are also off the road due to scarcity of repair parts. As a recent Atlantic magazine article reports, “Supply chains depend on containers, ports, railroads, warehouses, and trucks [and workers]. Every stage of this international assembly line is breaking down in its own unique way.”

In Vancouver, ocean-going containers of cheap manufactured crap from Asia arrive bulging, and make the trip back home mostly empty (a lot of their “cargo” on the return trip is plastic trash and scrap textiles). And containers of raw materials (much of it phosphates, sulphates and nitrates destined for Latin America to be used as fertilizer to support the continued massive clearcutting of the rainforest to plant crops) leave Vancouver bulging and return largely empty. Higher fuel costs now mean the ships have to travel at half-speed to use less fuel so they can “break even” cost-wise, adding to the vehicle shortage and hence the shortages and stock-outs of everything else.

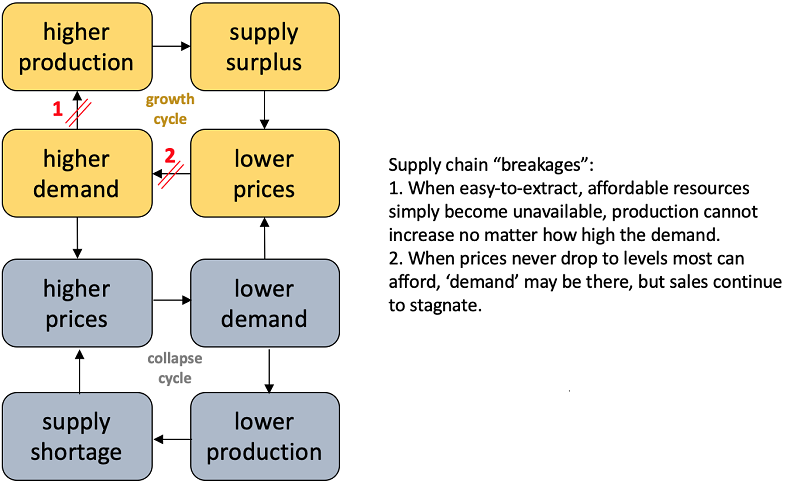

If this were just a temporary phenomenon, we would be able to live with it. But there’s considerable evidence we’re seeing what will emerge as a permanent, slowly deepening problem, as a precursor to a broader economic collapse. The following chart shows how the supply chains are now fraying and in danger of permanently breaking:

Supply chain breakages ~ Click the image to enlarge

In a “normal” industrial economy, the growth and collapse cycles balance each other out, keeping supply, demand, prices and production in equilibrium. However, because of the “limits to growth”, two parts of the growth cycle will inevitable start to break as the industrial economy comes up against the reality of unsustainability, in two ways:

- When resource supplies become scarce, such that they are uneconomic to produce relative to the spending power of consumers, it becomes impossible to increase production in response to an increase in demand.

- When products become unaffordable for many at any price, no amount of ‘discounting’ will be sufficient to increase sales, and hence there will be no incentive to increase production. The ‘demand’ is there, but those needing the goods and services can’t pay for them.

What we are seeing now are early glimpses of what will happen as those chains in the growth cycle continue to fray and finally break. The equilibrium will be lost, the growth cycle (yellow in the chart above) will cease, and we will be permanently caught in the collapse cycle (grey in the chart above).

This is what has happened in previous depressions and severe recessions, though in every case there was enough slack in the system to repair the ‘breaks’ and move the economic system back into equilibrium.

There is no longer any significant slack in the system. Bailouts of corporations and industries that cannot operate profitably because their products require scarce, expensive resources can only work when there is the potential of less expensive resources coming on line, or the potential of dramatically increasing most consumers’ spending power, and when the government can pump trillions of dollars into the financial system to bail them out until that happens, without collapsing the currencies, the financial systems, and the governments that rely on faith in the value of their currencies.

Once we realize that there is no short term “innovation” fix for (1) the ever-diminishing energy return on energy invested in the resource sectors (especially oil) on which the entire growth cycle and growth economy are based, (2) the chasm of inequality between the extremely rich and the increasingly impoverished vast majority, and (3) the current dependence on artificially-suppressed interest rates and the skyrocketing levels of unsustainable debt by citizens, corporations and governments, then the market will wake up to the reality of its overextendedness and unsustainability.

Then, the collapse cycle will become the only game in town — supply shortages driving up prices to the level consumers can’t afford to buy, yet still not high enough that producers can afford to produce and sell, endlessly lower ‘demand’ (not because products aren’t needed, but because very few can afford to buy them at any economically viable price), and collapsing production, aggravating the shortages. We’ve seen it many times before. It’s probably been a part of every civilizational collapse in one way or another. And we’re nowhere near ready for it, and won’t be until we realize these “supply chain problems” are early evidence of permanent economic collapse, and not just something we have to put up with for a while until the supply chains are magically “fixed”.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dave Pollard publishes the blog How to Save the World, a chronicle of civilization's collapse, creative works, and essays on our culture, searching for a better way to live and make a living, and a better understanding of how the world really works. For more information about this author, click here.

|