|

Mother Pelican

A Journal of Solidarity and Sustainability

Vol. 10, No. 4, April 2014

Luis T. Gutiérrez, Editor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Biocultural Heritage:

The Foundation of a Sustainable Economy

Claudia Múnera

This article was originally published in

The Daly News, 15 March 2014

under a Creative Commons License

Colorful vegetables, colorful meats, and even more colorful characters make up the scene at

Porta Palazzo, Turin, Italy (photo credit: Claudia Múnera).

|

|

Porta Palazzo in the city of Turin, Italy, is recognized as the largest open air market in Europe. Visiting this market provides a unique experience: vendors in all directions offer a seemingly endless supply of breads, pastas, meats, poultry, fish, vegetables, herbs, and olives. The kaleidoscope of colors and jumble of aromas threaten to overload the senses. Italians and foreigners alike gather here to find the foods they want – whether it’s a local ingredient for a traditional Italian dish or something exotic to summon the tastes of a faraway home.

Even though there’s such diversity, all the foods at Porta Palazzo share something in common. You can trace each type of food to a particular ecosystem and a particular way of life for the people who inhabit (or once inhabited) that ecosystem. Each food product in the market comes with its own biocultural heritage. Among all the products we buy and sell in today’s economy, food is probably the easiest to connect to biocultural heritage (assuming we’re not talking about a pre-packaged, frozen microwave dinner). For instance Colombians crave bocadillo veleños, the traditional confection made from guava and sugarcane. And Salvadorians keep an eye out for pupusas, which are made from a cornmeal dough that redefines the phrase “comfort food.” When living abroad, people from a given region often organize festivals in which traditional foods play a central role.

Biocultural heritage wraps a lot of concepts into one term. It’s about relationships between people and the natural environment. It consists of biological resources, from genes to landscapes. But biological heritage also consists of human history, from practices to pools of knowledge and the way humans shape their surroundings and vice versa. According to the International Institute for Environment and Development, some 370 million indigenous people in the world depend directly on natural resources — they rely on their biocultural heritage for survival. Biocultural heritage also influences religious beliefs, sense of place (especially sacred places), and sense of self. It’s easy to be overwhelmed by the tangle of connections when considering the biocultural heritage of a good or a service — maybe that’s why food is a good place to start when trying to get a feel for it. But an astute observer can recognize that other goods and services, such as medicinal plants, tourism, or even health services, also flow from a rich biocultural heritage.

Throughout my career, it has become increasingly clear that conservation of biocultural heritage is the long-term key to maintaining both healthy ecosystems and healthy economies. As a conservation biologist, I could probably be accused of having a biased viewpoint — I have always believed that endangered species, tracts of wilderness, and other aspects of biodiversity are intrinsically valuable and worthy of conservation. As a result, I have spent a lot of time and effort on projects aimed at protecting ecosystems and the species they contain. I believe that maintaining parks and protected areas is a worthy endeavor, but it’s not enough. Drawing boundaries around biodiversity hotspots or cherished scenic areas will fail in the face of ongoing exponential economic growth and mounting pressure to turn protected areas into commodities.

My research on biocultural heritage at the Rio San Juan Biosphere Reserve in southeastern Nicaragua aims to illustrate the point. Nicaragua is changing at a fast pace, trying to follow a European or North American model of economic growth at the expense of its rich natural capital. Deforestation is on the rise with forest cover diminishing from 42,340 square kilometers in 1994 to 30,440 in 2011. There are several causes, but the main one is to meet the demands of markets: cattle for dairy and meat, hardwood lumber, and crops such as palm oil, sugarcane, and peanuts. In short, forests are being transformed into commodity landscapes.

Biocultural services: chocolate tours in Rio San Juan Biosphere Reserve

(photo credit: Claudia Múnera)

|

The intense pressure applied by economic growth is threatening flagship species such as the jaguar and tapir, internationally significant wetlands, and the species-rich (not to mention carbon-sequestering) forests of this region in Nicaragua. In light of such pressure, the best way to conserve the natural areas is to recognize the value of the biocultural heritage of these areas. Local communities and indigenous populations are making a living and thriving by growing traditional crops, creating handcrafts, and preparing traditional foods that are founded on the local environment and framed in Nicaraguan history and culture. Several communities are embracing ecotourism (it’s a lot easier to entice a tourist to visit the Rio San Juan, Bosawas, or Ometepe Biosphere Reserves if they haven’t been converted to palm oil plantations or cattle farms). Farmers are also having a go at organic cocoa production. A certain amount and certain types of economic activity are compatible with the natural resources of the region, but if we fail to conserve the biocultural heritage of the region, the natural resources will eventually become commodities in economic activities that are incompatible with the landscape.

Other places around the world also demonstrate how championing biocultural heritage can produce desirable results for people and ecosystems. For example, the provinces of Guangxi and Yunnan, China, contain rice terraces, mountain agriculture, and forests that have provided people with livelihoods for centuries. During the last three years, however, droughts have threatened the economy and local food security. Farmers have relied on their biocultural heritage to cope — planting traditional drought-resistant maize varieties and raising ducks in the rice fields as a pest control strategy. Farmers have accrued health benefits by eliminating pesticides and earned profits by selling their products in niche organic markets.

In Tuscany, Italy, the landscape has been shaped and preserved by centuries of human influence, but in recent times, the people have been engineering the landscape into a homogenized agricultural landscape of mechanized monocultures with no consideration of traditional farming and forestry practices. Consequences include biodiversity loss, erosion, and deteriorating quality of life for residents who have strong ties to their landscape. According to UNESCO, “Cultural landscapes originated by human action, as well as biodiversity connected to them, can only be maintained by preserving local cultural heritage. Abandonment of traditional practices can lead to reduction of landscape diversity with impacts on biodiversity, economy, and quality of life of rural communities. To overcome these problems, parts of the landscape have been included in the World Heritage Sites list (Medici Villas and Gardens). At the same time, ecological restoration of agricultural and natural areas has spurred tourism, revitalized local foods production, and led to the creation of markets for locally grown food that help preserve Tuscan culture.

Protecting the biosphere comes down to making sure enough ecosystems around the globe maintain their structures and functions. A strong appreciation of biocultural heritage is a key to doing this job, especially in the face of pressures from ongoing economic growth. Local economies in which people maintain a sense of place and a sense of their ecological and cultural limits provide an alternative, resilient model to the infinite growth paradigm.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Claudia Múnera is a conservation biologist at Colombia’s National University and actively involved in conservation, birdwatching, sustainable development, and ecotourism projects in Colombia, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. She recently graduated with a master's degree in World Heritage and Cultural Projects for Development sponsored by the ITC-ILO jointly with University of Torino in collaboration with UNESCO World Heritage Centre. She is

director of CASSE’s Colombia Chapter, and a member of the IUCN-CEESP.

ABOUT THE CENTER FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE STEADY STATE ECONOMY

The Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy (CASSE) is a research group on economic sustainability located in Arlington, Virginia, USA. The mission of CASSE is "to advance the steady state economy, with stabilized population and consumption, as a policy goal with widespread public support." The CASSE website provides many additional research resources on economic growth, degrowth, and post-growth. For example:

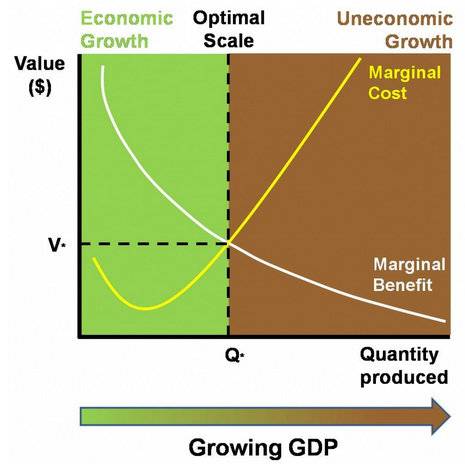

The following chart captures the basic rationales for the steady-state economy:

"Marginal cost refers to the cost of producing one more unit of a good or service. Marginal benefit is the benefit gained from one more unit. This graph shows the marginal costs and benefits of GDP growth. Costs tend to rise and benefits tend to decrease for each additional unit of growth. We should stop growing GDP, therefore, when marginal costs are exactly equal to marginal benefits. If costs are less than benefits, then GDP growth is economic (the green part of the graph). When costs rise above benefits, GDP growth is uneconomic (the brown part)."

|

Additional articles on the application of the fundamental steady-state economy concept to specifc issues can be found in the

The Daly News. The following is a list of recently published articles:

Steady Statesmanship Goes Global,

by Jon Rosales, The Daly News, 17 June 2013

Full Employment Versus Jobless Growth, Herman Daly, The Daly News, 15 July 2013

Entropia: Life Beyond Industrial Civilisation,

Samuel Alexander, The Daly News, 1 August 2013

Fixing Food and Farming with a True-Cost Economy, Brent Blackwelder, The Daly News, 6 August 2013

The End of the Age of Extraction, Brent Blackwelder, The Daly News, 2 September 2013.

Approaching a Steady State Economy, Part 1 — Getting Around, Rob Dietz, The Daly News, 9 September 2013

Approaching a Steady State Economy, Part 2 — Clean Clothes, Rob Dietz, The Daly News, 16 September 2013

Growth and Laissez-faire, Herman Daly, The Daly News, 23 September 2013.

Unlimited Competition Is Not Sustainable, Gunnar Rundgren, The Daly News, 30 September 2013.

Insanity Reigns at the World Bank, Brent Blackwelder, The Daly News, 14 October 2013.

A Question of Scarcity, Andrew Fanning, The Daly News, 21 October 2013.

How Many People Can a State Sustain?, George Plumb, The Daly News, 4 November 2013.

The Five Dumbest Things You’ll Hear About Sustainability, Brian Czech, The Daly News, 12 November 2013.

Top 5 Threats to the World’s Beaches (and a Systemic Solution), Brent Blackwelder, The Daly News, 18 November 2013.

The Hidden Door: Mindful Sufficiency as an Alternative to Extinction, Mark Burch, The Daly News, 16 December 2013.

Voluntary Simplicity and the Steady-State Economy, Mark Burch, The Daly News, 7 January 2014.

Toward a Finite-Planet Journalism, Eric Zencey, The Daly News, 3 February 2014.

An Economic Game Plan to Prevent Water Pollution, Brent Blackwelder, The Daly News, 17 March 2014.

What to Do When You Suspect We’re Headed for Collapse, Rob Dietz, The Daly News, 31 March 2014.

|

|Back to TITLE|

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Supplement 1

Supplement 2

Supplement 3

Supplement 4

Supplement 5

Supplement 6

PelicanWeb Home Page

|

|

|

|

"A happy family is but an earlier heaven."

— George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950)

|

|

Page 3

|

|

FREE SUBSCRIPTION

|

![[groups_small]](groups_small.gif)

|

Subscribe to the

Mother Pelican Journal

via the Solidarity-Sustainability Group

Enter your email address:

|

|

|

|