A Human Reflection From Wild Hogs

My apologies to any Tim Allen or John Travolta fans. This article is certainly about a film, but unfortunately Tim and John didn’t make the cast.

I. Introduction — Lessons Hidden in Plain Sight

Humanity stands in a moment of extraordinary paradox: we understand ecosystems better than any species in history, yet we routinely ignore the ecological lessons unfolding directly in front of us. We identify invasive species, population explosions, disrupted feedback loops, missing predators, and cascading ecological failures—all with scientific clarity. But when the mirror turns toward humanity, the same logic becomes strangely off-limits.

A recent example— a video by Incredible Stories, Everybody Laughed at Texas for Their Wild Boar Problem—offers one of the clearest illustrations of ecological imbalance in action. Yet the deeper lesson it reveals is not about hogs at all. It is a portrait of how humans respond to complexity, and more importantly, how we often refuse to see our own reflection in the ecological crises we analyze.

This article reframes the wild hog story as a learning moment, guiding educators and students toward a broader insight: the very patterns we critique in invasive species also describe the human trajectory. Recognizing this does not diminish humanity—it empowers us to design a more symbiotic future.

II. What Invasive Species Teach Us About Ourselves

The Texas feral hog crisis is familiar ecological territory. A species is introduced, encounters no natural predators, expands rapidly, and destabilizes the environment. Ecologists define an invasive species by its behavior, not its intent:

- rapid population growth

- expansion into new territories

- the absence of controlling factors

- degradation of habitat

- displacement of native species

- resistance to isolated control tactics

We apply these criteria to hogs, pythons, zebra mussels, cane toads, rats, lanternflies, and dozens more. Yet we rarely apply the same ecological reasoning to ourselves.

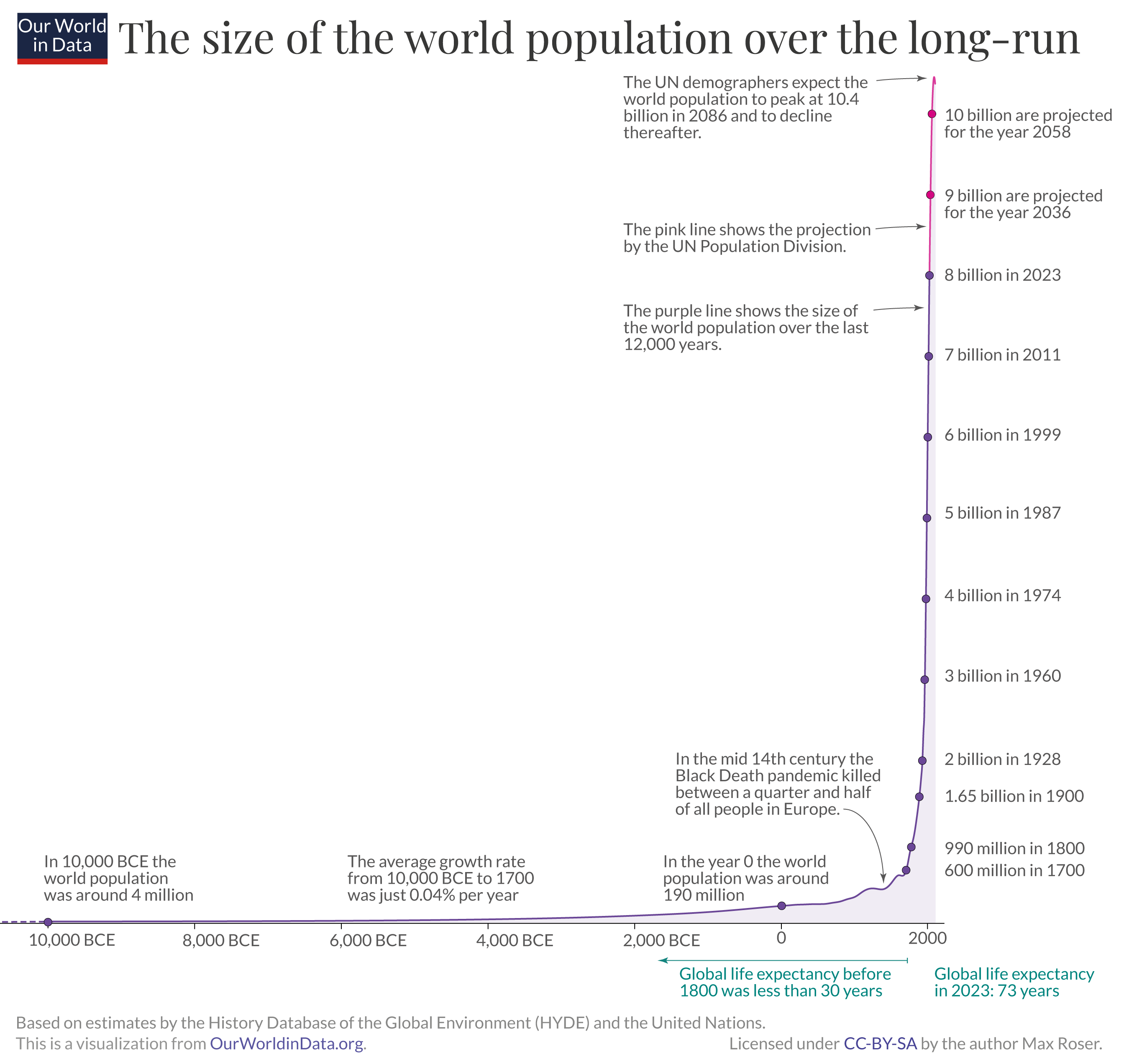

Human population has grown from roughly one billion in the mid-1800s to over eight billion today—a classic exponential curve recognizable in any ecological model. Coupled with industrial consumption patterns, technological buffering from natural limits, and global mobility, humanity now exerts ecosystem-level pressure on a planetary scale.

This is not an accusation. It is an ecological observation.

Recognizing our own pattern is not about moral judgment—it is about reclaiming the intelligence nature expects of us. We cannot change what we cannot name. And the first step in becoming a symbiotic species is acknowledging where our current trajectory aligns with patterns we clearly understand in other organisms.

Click on the image to enlarge.

III. From Linear Civilization to Circular Life

Nature operates on circular logic: nothing is wasted, everything becomes food for something else, and every system is embedded in a web of reciprocal relationships. Human civilization, in contrast, was built on linear assumptions:

take → make → use → discard

This model worked temporarily only because humanity was small, resource-rich, and buffered by vast wilderness. But in a world of eight billion people, linear systems inevitably produce:

- resource depletion

- ecological overshoot

- waste accumulation

- biodiversity collapse

- destabilized climate and water cycles

Circular systems—those that mimic natural flows—are not aesthetic preferences. They are survival architectures.

A circular human civilization includes:

- repairable, modular technologies

- cradle-to-cradle manufacturing

- regenerative agriculture that restores soil

- water and nutrient cycling

- renewable energy networks

- durable goods over disposable ones

- redesigning economies to reward regeneration

Circularity is not a sacrifice—it is a return to ecological sanity. And it is the foundation for any society seeking long-term stability.

IV. Coordinated Solutions for a Complex Species

The Texas hog documentary reveals a subtle but powerful truth: every control method worked—just not on its own . Trapping, hunting, fencing, aerial culling, landowner initiatives—all were partially successful. But because they weren’t coordinated, the system remained overwhelmed.

Humanity’s ecological challenge is similarly complex. No single strategy—population stabilization, consumption reduction, technological innovation, policy reform, economic redesign—will succeed alone. Each is necessary but insufficient without alignment.

A coordinated human response requires integrating:

- individual autonomy (especially reproductive, economic, and educational)

- systemic redesign (circular economies, regenerative agriculture, ecological infrastructure)

- policy frameworks (incentives for restoration over extraction)

- technological innovation guided by ecological principles

- community-level adaptation and resilience

- global cooperation on climate, biodiversity, and resource governance

Human beings are innovative, creative, adaptive, and capable of extraordinary collaboration. But we must move beyond the expectation of a singular solution. Civilization is an orchestra—not a solo performance.

V. Reality Check: Power, Resistance, and Greed

Ecological transition does not occur in a vacuum. Some actors—corporations, political factions, financial systems, and individuals—benefit directly from extraction and may resist change through:

- misinformation and manufactured doubt

- political obstruction and regulatory sabotage

- economic coercion and market manipulation

- legal aggression that delays or derails ecological reform

- intimidation or, in extreme cases, violence

This is not pessimism—it is realism.

Unchecked greed, concentrated power, and extractive incentives are among the most significant obstacles humanity faces. Ecological transition requires not only new technologies and new values, but also:

- democratic safeguards against corruption

- transparent governance and public accountability

- community resilience against coercive interests

- education systems capable of recognizing manipulation

Naming these dynamics does not weaken the ecological argument. It strengthens it by acknowledging the actual terrain educators and students must navigate.

VI. A Call to Action for Educators and Students

Educators and students occupy one of the most strategic positions in this transition. Before governments act or markets shift, cultural understanding must change—and classrooms are where that shift begins.

1. Teach ecological systems as the foundation of human systems

Population, consumption, and resource dynamics are ecological mechanisms, not moral battlegrounds.

2. Use invasive species case studies as low resistance mirrors

Students more readily grasp ecological imbalance through hogs, pythons, mussels, and toads—and then connect those lessons to humanity.

3. Embed circular thinking across disciplines

Every field—from engineering to economics to the humanities—benefits from ecological reasoning.

4. Reconnect learning to place

Local ecosystems provide living laboratories for stewardship.

5. Teach historical harms to anchor ethical transitions

Understanding past abuses (eugenics, forced sterilization, colonial exploitation) ensures future ecological policies remain voluntary, equitable, and just.

6. Cultivate complexity literacy

Ecological systems resist simple answers. Students must learn to work with uncertainty, nuance, and interdependence.

7. Empower regenerative imagination

A sustainable future is impossible to build if people cannot imagine one.

VII. Conclusion — Becoming a Symbiotic Species

Humans are not inherently invasive. We are a species whose power has outpaced its ecological maturity. Yet we also possess unmatched capacity for foresight, creativity, and ethical imagination.

Nature is not asking us to shrink, apologize, or disappear. It is asking us to grow up.

To embrace circularity.

To respect limits.

To coordinate our intelligence.

To confront harmful power honestly.

To educate for stewardship.

To practice reciprocity.

To become a species that strengthens the web of life instead of unraveling it.

The invitation is clear: let us be the first species to recognize our own pattern—and choose a different one.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gregg Lavoie is a graduate of Northeastern University’s college of Business Administration. In his diverse career across multiple industries, he has been a leader in the management of numerous industrial manufacturing facilities, found success in B2B sales, has spearheaded the creation and deployment of quality assurance operations and has designed, created and successfully established multiple employee training and educational programs in manufacturing as well as software development organizations. Now retired, Gregg is still passionate about improving the well-being of humanity and improving the human experience into the future. Gregg firmly believes that this can only be possible if humanity can first come to understand and appreciate that our existence is 100% dependent on the Earth, its resources, environmental systems and diversity of life. Gregg advocates that as the most advanced species on the planet it is our duty and primary responsibility to ensure we live in a manner that without question guarantees the health of the Earth as well as the balance and stability of its systems and the abundance of biodiversity. This will not happen unless the human species can educate itself to adopt more sustainable, cooperative and environmentally friendly fundamental methods of existence.

|

|Back to Title|

LINK TO THE CURRENT ISSUE

LINK TO THE HOME PAGE