Climate activists and climate‑change deniers are unhappy in the same way. Both see the world as a machine that just needs a tune‑up or a few replacement parts to work properly again.

For activists, the solution seems obvious: replace fossil fuels with renewables and everything will be fine. Deniers prefer a different fantasy: technology will sort out whatever minor issues climate change brings. Both miss the real danger — we’re destroying the planet’s ecological life-support system.

The climate debate is like arguing over a fever instead of treating the infection. It’s a fight about symptoms, proxies, and secondary effects — not the disease that’s killing the patient. That’s why deniers have been so effective at attacking the main proxy, CO₂. When you reduce the problem to a single measure, you give the critics an easy target: challenge the measurements, the historical record, or attack the people taking the readings.

Blaming fossil fuel companies became yet another distraction. Instead of accepting growth as the root cause of climate change, we shifted to emissions accounting, corporate guilt, and energy substitution — second-derivative arguments that led to even more pushback. Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion take this to an extreme. They don’t seem to understand that stopping oil abruptly would collapse the systems keeping billions of people alive. Ending oil overnight wouldn’t “save the planet” — it would cause a humanitarian catastrophe.

Temperature is a slightly better proxy than CO₂. It’s shows the body is under stress. But it’s still just a signal, and not the cause. We’re stuck debating whether the fever stops at 1.5°C, 2°C, or 3°C, as if that settles anything. The same is true for 400 ppm or 450 ppm CO₂. We’re already in the danger zone at 425 ppm so this gets dismissed as alarmism by deniers. Meanwhile, the underlying disease goes untreated.

That disease is ecological overshoot. Humanity is consuming and degrading nature faster than it can regenerate. Climate change is just one symptom. Biodiversity collapse, soil exhaustion, freshwater depletion, pollution, and ocean acidification are others.

Introduce overshoot into the debate, and you’ve crossed a line: economic growth. Growth is assumed, expected, and required. That’s why climate change was never going to be addressed seriously.

The signs of ecological collapse are undeniable, and so is the cause: human expansion. Pollution, deforestation, and ecosystem breakdown are direct consequences of our actions. Climate change, by contrast, has more complex drivers and proxies. Making it the central issue was a major unforced error—one that has distorted the conversation and can’t be reversed easily.

Degrowthers diagnose the problem correctly: growth is the issue. But their prescription is delusional. They think people and governments will accept less—even though modern civilization is built on the promise of more.

At this stage, shifting the debate from climate to overshoot isn’t realistic. So the downward spiral continues. Activists double down on partial solutions. Deniers dig in. And then Bill Gates declares the climate debate basically settled—which might have been the final nail in the coffin.

This is where the doomsday cult declares victory. No hope. No path forward. Collapse is inevitable. In a universe full of uncertainty, doomers cling to certainty. They are the epitome of left-brain, black-or-white, ego-inflated thinking.

Each group — activists, the deniers, Just Stop Oil, and degrowthers — sees one piece of the problem, but none can see the whole. How did a species that named itself Homo sapiens — “wise man” — become so blind to its own predicament?

Iain McGilchrist offers a powerful answer in The Matter With Things:

“I believe we have systematically misunderstood the nature of reality…The problem is that the very brain mechanisms which succeed in simplifying the world so as to subject it to our control militate against a true understanding of it.”

His hemisphere hypothesis is, in my view, the best science-based framework for understanding human behavior. The brain has two complementary ways of looking at the world. The left hemisphere is narrow, literal, analytical and focused on control and explicit rules. The right sees the whole in context. It’s intuitive, relational, comfortable with ambiguity and nuance, and attuned to meaning.

We need both. But the left hemisphere doesn’t share power. It believes its model of reality is reality. It jumps to conclusions, and defends them even when facts don’t fit. It doesn’t know what it doesn’t know. And over time — especially in the modern West— its worldview has become dominant: reductionism, abstraction, measurement, technocratic control, and the belief that the world is a machine.

A left-brain civilization sees the world as things to be used, not relationships to be honored. Every problem has a solution. It just needs with more control, more technology, more efficiency, and more growth. Limits are negotiable. If the model says the system is fine, it must be.

The right hemisphere knows better. It sees that everything connects, often in non-linear and unpredictable ways. “Solutions” increase complexity and shift the problem somewhere else. Engineering the future is dangerous because we can’t see all the consequences.

McGilchrist explains why each camp in the climate debate thinks it’s right. Everyone is right about their narrow part — and wrong about the whole. Until we recover the right hemisphere’s way of knowing — context, relationship, humility — we will keep arguing over fragments while the system unravels around us.

That is the message of the elephant and the blind men parable. A group of blind men come across an elephant for the first time. Each touches a different part of the animal. One grabs the trunk and says, “This is a snake.” Another feels the leg and insists, “This is a tree.” A third touches the side and declares, “This is a wall.” Each man is convinced he understands the whole based on the small part he encountered. But none can see the full elephant. Their arguments grow, because each is right — and completely wrong — at the same time.

The parable warns against mistaking a part for the whole — especially in complex systems.

Illustration provided by the author. Click on the image to enlarge.

Policy changes, technology, and more information won’t change this. The problem lies much deeper. It’s how we think, how we see reality, and the relationship we have with the living world. That last part is so broken that most of us don’t even consider ourselves part of nature.

Consider addiction. Around 30-40 million Americans struggle with alcohol or opioid addiction but rehabilitation centers aren’t overflowing. Most addicts don’t seek treatment, and about half of those who do relapse within a year. That’s because addiction isn’t solved by information or willpower. It requires a psychological shift in how a person sees themselves, others, and reality.

Now scale that to billions of people and a planetary crisis most of them don’t believe exists. Expecting society to voluntarily change quickly, peacefully, and rationally is like expecting every alcoholic to wake up tomorrow, check into rehab, and achieve lifelong sobriety on the first try.

Change happens, but almost never in a business‑as‑usual context. In the case of our present predicament, a shock that shakes civilization to its core may only be enough to briefly raise awareness, and silence deniers until they think of another excuse to dismiss the obvious. The unfortunate downside of trauma is that it makes many people double down on the behaviors that worked for them in the past. Left-brain thinking values cooperation only when it serves self-interest or advances personal gain.

For the minority who genuinely care — perhaps similar to the ~20% of addicts who seek treatment — we need to think in evolutionary time: decades to centuries.

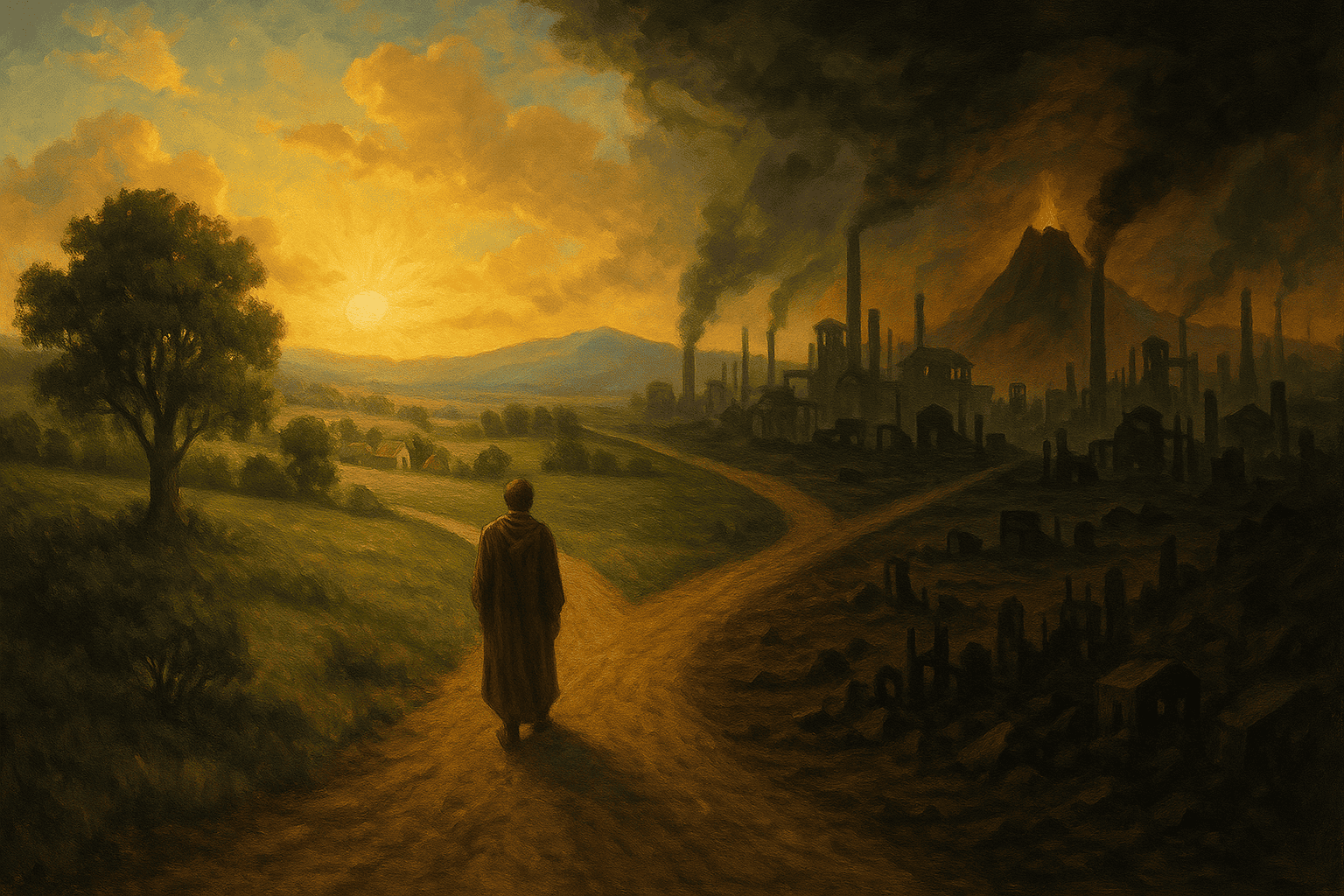

Nate Hagens calls this transition The Great Simplification. When global systems unravel, energy becomes harder to access, supply chains break, debt becomes unproductive, and trust in institutions collapses. The default path is what he calls The Mordor Economy: rising costs, declining living standards, and mounting debt until the system buckles.

The better path is to bend, not‑break. It means accepting the end of growth, simplifying intentionally, and redirecting human effort toward community, sufficiency, and meaning.

Illustration provided by the author. Click on the image to enlarge.

Hagens thinks a forced post‑growth future is more likely. Some mix of financial collapse, war, supply-chain failure, and ecological crisis triggers a shift in awareness. A simpler society emerges: more local, less complex, and focused on well-being. But that only works if an advance team has already built the tools, technologies, and education needed to guide the transition.

Another ingredient is essential. Culture is how we transmit knowledge and meaning across generations. It’s the evolutionary medium for adaptation. For most of history, that was done through myth, story, and sacred practice. That wisdom tradition has been eroding for centuries—never faster than now.

Paul Kingsnorth argues that the West isn’t collapsing—it’s already dead. Without a shared story, society falls apart. He calls this a civilizational delusion.

McGilchrist identifies the root cause. The left hemisphere mindset — literal, utilitarian, mechanistic, obsessed with control — has eclipsed the right’s wisdom. A culture that values only what it can measure and manipulate becomes blind to myth, reverence, and the living world. When that dies, ideology and techno-fantasy rush in to fill the void.

Carl Jung might say that the West is in a mass psychological breakdown. The ego has cut itself off from the unconscious — our species-level memory. We’re trapped in ego-inflation and have lost touch with the soul. Jung wouldn’t recommend a new ideology. He’d tell us to reconnect to the archetypal, the symbolic, and sacred — or the breakdown will get worse.

McGilchrist, Kingsnorth and Hagens are cautiously optimistic that there is a way through the dilemma. I take the Jungian view. We must reverse a deep psychological disorder centuries — maybe millennia — in the making. That won’t happen without the collapse of the “old personality” of civilization, and that’s a psychological crisis that requires careful guidance.

Policy, technology, and information can’t cure a spiritual disorder. Climate change and overshoot are symptoms of Jung’s “psychic shadow.” The root is the belief that we are entitled to dominate nature and exploit the Earth without limit. Most people can’t—or won’t—let go of that belief.

Jung wouldn’t promise success. He’d say it depends on whether a meaningful minority chooses inner transformation over ego, power, and salvation through technology. The odds are low — but not zero. Historically, civilizations have been reborn by small bands who carried the flame through the dark, but it takes time, and we moderns are an impatient crowd.

I imagine something like a modern Exodus. A few will follow Moses out of bondage to the superorganism, and go into the wilderness. It will take at least a generation — with golden‑calf relapses along the way — before transformation becomes possible. Most won’t make it. The hope is that a few will cross the Jordan to the other side.

Real change has always been — and will always be — psychological. People keep asking for a solution. Here it is. The Great Simplification isn’t just a response to breakdown; it’s the way forward. And like all true transformations, it begins from within.

By the same author:

Energy Reality: What Can't (and Won't) Happen

The Mirror, Not the Monster: What AI Reveals About Us

The Long Twilight of Growth

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Art Berman is Director of Labyrinth Consulting Services, Sugar Land, Texas, and a world-renowned energy consultant with expertise based on over 40 years of experience working as a petroleum geologist. Visit his website, Shattering Energy Myths: One Fact at a Time, and learn more about Art here.

|