In 1858, Charles Darwin received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace explaining that natural selection was the driving force behind evolution. Darwin later said it struck him like “a bolt from the blue,” because Wallace had captured in a few pages the insight Darwin had struggled to articulate for years.

I had a bolt from the blue when I came across John Dupré’s The metaphysics of evolution.

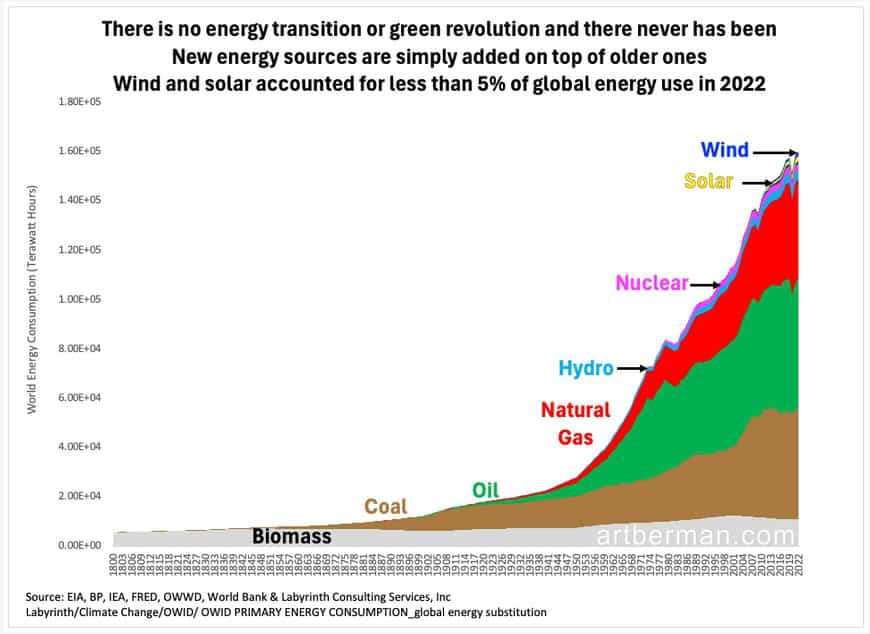

I’ve long thought the whole idea of a renewable energy transition is a fantasy—something with no basis in history or physical reality. There is no transition, only addition. Renewables are built on fossil foundations; total energy use keeps rising; and the dream of replacing hydrocarbons without collapsing growth or affordability is an illusion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. There is no energy transition or green revolution.

Source: EIA, BP, IEA, FRED, OWWD, World Bank & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

Click on the image to enlarge.

|

That approach isn’t wrong but it’s reductive. It treats energy like a kit of parts—coal, oil, natural gas, and renewables—that you might buy at Home Depot to build a shed. Swap one piece for another and assume the structure stands the same.

“The metaphysical question…is an ancient one, the debate whether the world is ultimately composed of things, perhaps eternal and immutable things as was proposed by the Greek atomists, or rather is everywhere in flux, as famously advocated by the Greek philosopher Heraclitus. For process philosophers, enduring things, rather than being the more or less unchanging furniture of the world, are never more than patterns of stability in a sea of process.”

John Dupré

Dupré asks whether the world is made of things or processes. Since at least the seventeenth century, science has mostly taken the “thing” view—the world as built from solid parts. It treats reality like a car engine; you can take it apart, lay out the pieces, and study how each one contributes to the motion of the whole. The pistons move because the fuel ignites, pushing the rods, turning the crankshaft, driving the wheels. Understand each component and its connection, and you’ve explained the system.

This mechanistic model has taken us far—it builds machines, predicts outcomes, and gives us control over matter. But it leaves something essential out. Living, evolving systems—whether in nature or society—aren’t machines made of fixed parts. Society, the economy, and political systems aren’t things—they’re processes. Like species or ecosystems, they exist through continuous activity and change. Their “parts”—people, institutions, technologies—come and go, but the larger pattern endures through the flows that connect them: communication, exchange, laws, culture, and energy.

“Species have somewhat vague boundaries…No one expects a thunderstorm or a battle to have precisely delineated boundaries. In fact, similar problems apply to organisms. Anyone who believes in superorganisms, for example ant colonies, that may include, as well as various castes of ant, domesticated fungi and several essential consortia of microbes, is happy with discontinuous organisms.”

A process doesn’t need rigid boundaries to stay coherent; it holds together through ongoing interactions, like a storm or an ant colony. Humanity itself functions as a kind of superorganism—an interconnected web of people and systems that sustain one another. Society, the economy, and politics are its metabolism, the processes through which this larger organism organizes, circulates, and renews its collective life.

They persist not because they’re made of stable parts, but because they continually reorganize to maintain their patterns. From a process perspective, they’re alive—self-organizing flows that survive through constant movement, repair, and exchange. They grow, adapt, decay, and reshape themselves as conditions change. Yet we still treat them like machines that can be optimized or fixed by adjusting a few variables. Economists model the economy with neat equations of supply and demand. Policymakers see politics as a system of inputs and outputs—votes, laws, incentives. And we approach climate change as if it were an engineering problem: swap renewable energy for fossil fuels, tweak the design, and expect the machine to run the same way.

Illustration provided by the author. Click on the image to enlarge.

|

But human civilization, like any living system, depends on balance and interdependence. The economy, politics, culture, and technology aren’t separate mechanisms but interlocking processes operating on different timescales—like cells, organs, and tissues in a body. Each holds its shape through internal activity while drawing stability from its exchanges with the larger whole. Humanity is an evolving superorganism whose health depends on the quality of these connections. Its systems stay alive only by moving, adapting, and transforming—something no machine can do for long.

The human superorganism—and its financial, geopolitical, supply-chain, governance, and energy systems—are deeply interdependent, both with one another and with Earth’s ecosystems. Like every living organism, this superorganism depends on metabolism—the continuous exchange of energy and materials with its environment.

Life exists in a state of thermodynamic disequilibrium, always working to stay far from balance. When that exchange stops, disequilibrium collapses. That’s death. A parked car can sit idle for months and still start when needed. A human left in the garage becomes a corpse. The same rule applies to civilization: when we degrade the environment that sustains us, we degrade ourselves, and the process that keeps us alive eventually fails.

Our mechanistic worldview also ignores culture—another living system that shapes and sustains human behavior. People belong to overlapping groups—families, workplaces, communities, faiths, and nations—creating a dense web of social connections. These networks form larger “supra-organismic” structures that evolve and adapt over time.

Dupré’s process view of evolution leads to a striking conclusion: evolution’s deeper function is not endless change but stabilization—the maintenance of coherent life processes within Earth’s dynamic environment. Natural selection is mostly stabilizing selection. Evolution is Earth’s feedback mechanism. It continually tunes the relationships between organisms and their surroundings to sustain the delicate thermodynamic disequilibrium where life persists.

This suggests that novelty isn’t the goal of evolution but an unexpected result of complexity. Human evolution has produced unprecedented novelty—our farms, transport networks, and cities—all examples of what biologists call niche construction, like beaver dams or termite mounds. But the scale of human niche construction has become deeply destabilizing. Evolution now seems to be responding with powerful stabilizing forces of its own—potentially including mass extinction or sharp reductions in population.

An equally important insight, though not stated by Dupré, is that process metaphysics makes the traditional idea of emergence largely redundant.

Emergence once served as a workaround for the mechanistic worldview, invented to explain how life and other phenomena could arise from inert particles. When properties couldn’t be reduced to the behavior of parts, they were called “emergent”—a conceptual fix to rescue reductionism from its limitations.

Process metaphysics eliminates the need for that fix. There are no fundamental parts from which wholes emerge—only flows of interaction nested within larger flows. What we once called emergent properties are simply patterns of temporary stability, like eddies in a stream or Jupiter’s red spot, sustained by the dynamics around them. The world is process through and through. Emergence was an artifact of reductionist thinking, made obsolete once we see that living systems never arose from dead matter because the flow was never dead to begin with.

The move from a mechanistic thing ontology to a process ontology replaces a commitment to strictly bottom-up causality with a recognition that whole systems help determine the properties of their parts.

The energy transition rests on a mechanistic illusion—the belief that we can replace one set of energy “things” with another and keep civilization running as before. But energy isn’t a thing. It isn’t a stack of interchangeable parts to be swapped out like building materials at Home Depot. It’s a process—a continuous flow that holds civilization far from equilibrium.

As Dupré showed in biology, we’ve tried to turn the living process of energy into a collection of parts. Energy is the metabolism of the human superorganism. Oil, coal, wind, and solar aren’t the point. The system only requires power, and the ways we classify energy sources are irrelevant. What matters is the stability of the whole, which depends on the networks of labor, infrastructure, finance, and ecosystems that support it—all moving together as one integrated process.

Forcing novelty onto this system through rapid renewable expansion risks destabilizing both civilization and its supporting environment. The energy transition isn’t just naïve—it’s potentially destructive. We can’t treat Earth like a race car that needs new parts; we must learn to move with the flow of living systems, not against them. Swimming upstream against nature’s current never ends well.

Earth’s systems are already signaling human-induced instability, and climate change is only one symptom. We are depleting resources and poisoning the very ecosystem that sustains our metabolism. This isn’t a technical problem to “solve” but a condition that demands adaptation—aligning human activity with the slower, evolutionary pace of the planet’s processes.

Energy and material decline are facts unfolding within a single human lifetime. The question isn’t whether we can stop the thermodynamic descent, but whether civilization can reorganize around lower metabolic demands without losing coherence and collapsing. What’s clear is that the mechanistic fantasy of seamless substitution through an imaginary energy transition isn’t a solution—it’s a dangerous delusion.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Art Berman is Director of Labyrinth Consulting Services, Sugar Land, Texas, and a world-renowned energy consultant with expertise based on over 40 years of experience working as a petroleum geologist. Visit his website, Shattering Energy Myths: One Fact at a Time, and learn more about Art here.

|