Ecosystems as Models for Restoring Our Economies to a Sustainable State, by John H. Giordanengo, Anthem Press, April 2025, is a book that every person interested in social/ecological justice should read. Focused on the tripod of Diversity, Energy, and Trade, the book provides a holistic model of how the economy works, and how it should work if industrial civilization is to survive the inevitable transition from the current state of continuing expansion to a sustainable steady state within the limits of the ecosphere. The model is anchored on how ecosystems self-regulate and restore themselves after disturbances; and this is the way to follow if we are to restore economies for long-term sustainability.

Having done (50 years ago!) my doctoral dissertation on the dynamics of secondary succession in ecosystems, the book was very appealing to me as soon as it was published. After studying it, and thus acquiring a better understanding of how economic dynamics can and must imitate ecosystem dynamics, there is no doubt in my mind that economies, embedded as they are in the planetary ecosystem, can transition from growth to steady-state if, and only if, the so-called 'externalities' (natural resource inputs, toxic waste outputs) are fully integrated in economic policies.

The core of the book is structured in three parts and fifteen chapters, as follows:

Part I: The Structure of a Sustainable Economy, and the Challenges of Capitalism to Build It

1. The Challenges of Capitalism in a Poorly Structured Economy

2. The Global Market Economy: Failing to Deliver in a Rapidly Changing World

3. The Obscure Structure of Highly Complex Systems

4. The Archetype of a Self-Regulating (Sustainable) Economy

Part II: The Foundational Components of a Self-regulating and Sustainable Economy

5. The Untapped Power of Diversity

6. Energy’s Influence on Diversity

7. The Balance of Trade

8. Scale Matters: The Natural Geography of Homo Sapiens

Part III: A Natural Roadmap for Economic Restoration

9. Evolution, Succession, and Economic Restoration

10. Restoring the Foundations of Our Economies: Agriculture

11. The Coevolution of Manufacturing and Waste-to-Resources

12. Restoring an Energy-Neutral Economy

13. Transitions to a Restored Economy

14. The Fringe Benefits of Economic Restoration

15. The Path of Most Resistance

Part I describes the 'obscure' (feedback-intensive interconnections) structures between economies and the natural habitat win which they are nested. Understanding the emergence of behavior modes as system boundaries expand is crucial; else, 'solutions' become more vexing problems. Part II explains that the three key components of both economies and ecosystems are diversity, energy, and trade. Energy is the enabler, and trade is the 'operating system,' but diversity is what actually makes energy work via trade. Let this sink in. Part III then provides guidance for economic restoration initiatives that can follow a succession of stages at various levels (local, regional, global) after the great acceleration disturbance precipitated by the discovery and subsequent pervasive burning of fossil fuels. This is where we are at the moment.

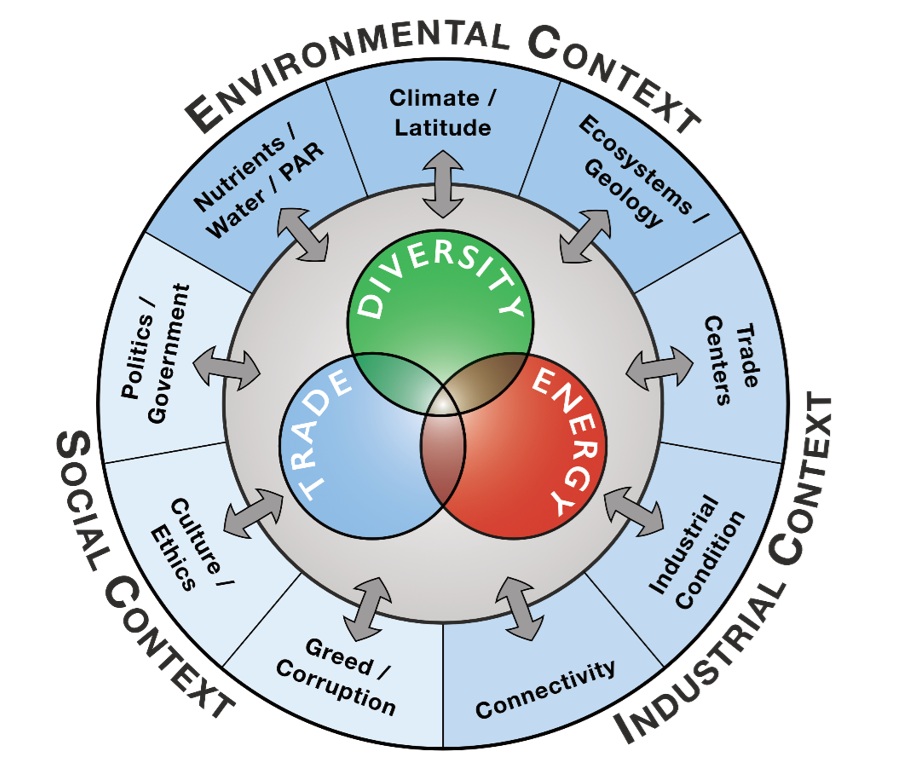

Figure 3.1 (page 59) is a jewel. It shows the tripod of diversity, energy, and trade in context, and makes the case for the impossibility of a sound economy that functions in isolation from the biosphere in which it is embedded (the environmental context) as well as the social and techno-industrial contexts.

Figure 3.1, page 59 of the book. The structure of an economy consists of its foundational components—diversity, energy, and trade—and the external forces interacting with them. A few common external forces are represented in the chasing arrows. Reproduced with permission. Click on the image to enlarge.

|

Diversity is the first leg of the tripod. Diversity in the economy is crucial for the same reason that it is crucial in ecology: it increases the capacity for resistance and resilience. Resistance to sudden disturbances, resilience to recover after such disturbances. Resilience is even more important than resistance, because the destabilizing effects of some disturbances cannot be evaded. In ecosystems, this capacity for resilience is known as secondary succession, which entails the recovery of lost biomass via successive phases of vegetation regrowth. In economies, the capacity to recover from recessions is contingent on the diversity of production and consumption, i.e., not putting all your eggs in one basket. Diversified economies are more resilient than those that depend on a single industry.

Energy is the second leg of the tripod. Energy enables all forms of human activity, but energy throughput is a double edge sword. More energy throughput induces more entropy and the need for spending more energy on negentropic actions; so simply increasing anergy supply is no economic solution, especially when primary energy becomes harder to extract and therefore more costly. There is an

energy cost of energy, and there is a

net energy cliff that must be avoided is an economy is to be restored to working order. The book explains biophysical energy realities and usage trends, and summarizes them succinctly: "As energy costs rise, the cost of extracting and distributing energy also rise, stoking a vicious positive feedback loop."

Trade is the third leg of the tripod. All trades entail resource transfers. Ecosystems do the transfering locally via food chains from producers (plants) to consumers (animals) and very efficient recycling via decomposers (bacteria and fungi). Modern economies do most of the transferring by importing energy and other resources from outside, with cities importing practically everything from rural areas. Globalization is about transferring resources via long supply lines on a global scale, thereby consuming enormous amounts of energy (mostly, fossil fuels). This unnatural trading of resources is furter enabled by financialization, which entails debt creation and makes the entire global economy (and therefore all the embedded national economies) more unstable. The book makes the case that defying the rules of self-regulating systems does not bode well for modern techno-industrial economies.

In brief:

|

Unbreakable Bonds between Diversity, Energy, and Trade

"Diversity, energy, and trade form predictable interactions in both economies

and ecosystems. Highly diverse systems can more efficiently extract energy and

other endogenous resources from within their ecological or economic space,

compared to low-diversity systems. However, transferring exogenous energy

and exogenous resources into the system reduces diversity. Highly diverse

economies confer benefits such as high resistance and resilience to disturbance

(stability), greater NDP and productive capacity, employment stability, stable

wage growth, sustained profitability, increased opportunities for a greater

diversity of people, and higher materials use efficiency. By their nature, highly

diverse economies also distribute wealth across a greater number of businesses

and individuals, wealth that is generated at the base of a balanced trade pyramid.

Producing and sustaining these benefits requires that diversity, energy,

and trade be restored as one interwoven whole. And for restoration efforts to

be successful, they must be applied at the right scale."

|

In the ultimate analysis, it is a matter of scale: approximately 8.2 billion people (9.7 by 2050?) consuming as much as they can afford and polluting accordingly. Can this global system be restored to sustainable stability? The book offers this definition of economic restoration: "the process of rebuilding economic diversity, endogenous trade, and endogenous energy systems within a regional economy." But how are we to manage regional economies when the entire system is structured in terms of national economies and national governments? Without a doubt, regional economies commensurate with regional ecologies could be restored to sustainable stability, and Part III of the book offers many proposals for sensible human agency to that effect. Figure 4.1 (page 69) on secondary ecosystem succession / biomass accumulation, and Figure 9.3 (page 192) on economic succession / capital accumulation, convey the striking similarity of the dynamics to be managed following the current phase of demographic/economic overshoot.

But given human nature, conditioned by millennia of patriarchy and wealth accumulation, it is doubtful that regional economies can be recognized as such and managed accordingly for the common good. In this regard, the book would seem to understate the (insurmountable?) obstacles that will prevent the emergence of some humanitarian form of global governance guided by the principle of subsidiarity. At a time when wars are erupting for nationalistic reasons and/or competition for increasingly scarce natural resources (e.g., energy, minerals, land) it is hard to imagine that national governments can peacefully negotiate economic policies pursuant to regional ecological restorations, let alone regional economic restorations. The last sentence of the book reads: "The greatest economy is not some golden era of capitalism in the past; it is that which lies ahead." But what kind of economy lies ahead?

Lest nostalgia about the past induce false hopes, it is clearly explained that economic restoration is not a matter of regressing to material/financial growth as the primary goal of economic policy. Rather, it is about progressing to economies that seek to meet human needs, as subsystems of the ecosystems that constitute the human habitat, for the sustainable viability of both humanity and the biosphere. The specifics of how to embed economies in ecosystems have yet to coalesce as a new economic-ecologic paradigm. The book is a significant contribution by providing a synthesis of the best current initiatives in this direction, with concrete real life examples, annotated references with hyperlinks, and a comprehensive glindex (glossary/index).