Many animals avoid contact with people. In protected areas of the African savanna, mammals flee more intensely upon hearing human conversations than when they hear lions or sounds associated with hunting. This fear of humans affects how species use and move in their habitat.

Throughout our lives, we interact with hundreds of wildlife species without stopping to think about it. These interactions can be direct, such as encountering wild animals while hiking in the mountains or driving through rural areas —or more deliberate, as when we engage with wildlife for food, sport or trade. As hunters, fishers and collectors, we kill more than 15,000 species of vertebrates —one-third of known diversity— a range of prey 300 times greater than that of any other predator our size.

Now, let’s look at it from the other side. Anyone who has survived an attack or a fatal accident, they understand that the experience is remembered for a lifetime. Likewise, animals store information about threatening or harmful encounters with humans. For them, adjusting their behavior in response to human presence has implications for their survival and reproduction, which are passed down from generation to generation. This ability to adapt, for example, determines which individuals, populations and species coexist with us in urbanized environments.

Response to dangerous sounds

Liana Zanette and her team measured the flight responses of wild mammals in the Greater Kruger National Park (South Africa) when exposed to sounds that signal danger [video-summary]. To do this, Zanette recorded videos of more than 4,000 visits to 21 waterholes by 18 mammal species. During each visit, a speaker attached to a tree randomly played one of five playback sounds: hunting dogs barking, gunshots, lion growls, human conversations in a calm tone and, as a control, the songs of harmless birds.

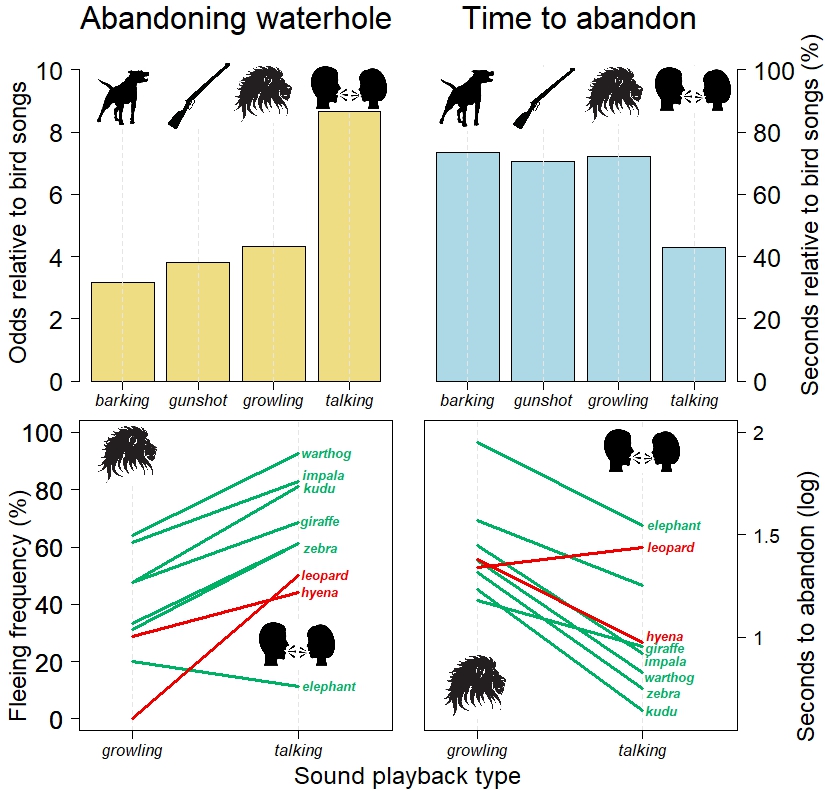

Overall, animals fled in one out of every three recorded scenes. The four dangerous sounds caused them to flee before and more frequently than the bird songs. Notably, animals fled twice as often and 40% earlier upon hearing human voices compared to lion growls. The average time to abandon a waterhole varied by sound: 14 seconds (humans), 23 seconds (dogs, gunshots, lions), and 32 (birds) seconds. Response times (medians) also varied by species: from 2 seconds (African wild dog Lycaon pictus) to 100 seconds (African elephant Loxodonta africana).

Weighing up to 200 kg, the lion (Panthera leo) is Africa’s largest feline and the continent’s apex predator, capable of hunting virtually any animal, including young elephants see lion facts and documentary list on this big cat. Since the Pleistocene, lions and humans have shared territories, both employing highly effective group-hunting strategies.

Flight behavior in 18 mammal species of Greater Kruger National Park (South Africa) in response to sounds played at 21 waterholes. See research video-summary.

Sounds at 60 decibels were played when animals approached a waterhole and triggered a motion sensor, which activated video recording. Each video captured a 30-second sequence consisting of 3 seconds of pre-sound recording, 10 seconds of playback, and 17 seconds of post-sound observation. In total, 4,239 videos were recorded across 14 variations of five playback types, including dog barks, gunshots, lion growls, human voices, and bird songs, with sample sizes ranging from 27 recordings of leopards to 991 of impalas. The results showed that animals fled eight times more frequently in response to human voices than to bird songs, and they departed the waterholes 40% faster when hearing humans. Flight responses to other sounds were generally less pronounced. Among the nine most flight-prone species, human voices triggered a higher proportion of flight responses and shorter departure times compared to lions, except for African elephants, which fled more often at lion sounds but still left sooner when hearing humans. Leopards displayed the opposite pattern. Overall, human voices exerted the strongest influence on both the likelihood and speed of flight across most species.

|

However, only our species can be considered an “unsustainable superpredator”. Unlike other carnivores, (i) humans are overpopulating the Earth, and (ii) our ability to kill has no natural limits: it is not solely dependent on physical skill but also on advanced technologies which, to some extent, are regulated by cultural factors such as resource-exploitation laws. Research like Zanette’s suggests that wildlife has learned to fear us: they definitely know how we roll. Importantly, if animals avoid humans in protected areas where activities are regulated to varying degrees, this avoidance, and its impact on species’ life histories, is likely to be even more pronounced outside these zones, depending on the type and intensity of human activities.

Fear as part of the landscape

The concept of the “landscape of fear” refers to how animals perceive the risk of being attacked depending on where they are within their habitat — related to the concepts of ecology of fear and nonconsumptive effects. A lower presence of wildlife in an area frequented by a predator, whether human or animal, does not necessarily mean the predator has wiped them out; rather, their prey might have simply moved elsewhere. Thus, in the African savanna, large herbivores tend to avoid waterholes that lions frequent, especially at night when the king of the jungle is out hunting. The landscape of fear intensifies with the mere presence of humans, and its effects ripple through the food chain. A clear example is the mountain lion (Puma concolor) in North America. These carnivores avoid urbanized areas or take longer to return to them after encountering people. As a result, deer populations increase in these areas, leading to more intense browsing of vegetation and a shift toward shrub-dominated landscapes.

Human presence shapes the behavior and movement of wild animals, even if they remain unseen and even in protected areas. This cause-and-effect relationship is difficult to measure and has been studied more in conspicuous bird species. Zanette argues that many species react negatively to human voices in a systematic way. Guided by fear, they flee without pausing to assess whether a person is harmless (e.g., walking or taking photographs) or dangerous (e.g., armed with rifles). This justifies setting visitor quotas for parks and reserves, a practice already in place in Western countries.

Nevertheless, in Africa, many protected areas rely on tourism for funding, making it inadequate to restrict visitor numbers. Alternative strategies might be needed to help animals become accustomed to human presence, as has been done with gorilla and great ape tourism — see TED talk and expert discussion. These measures, however, are controversial. Familiarization with humans could lead to behaviors resembling domestication, potentially making prey more vulnerable to their natural predators. Ultimately, understanding and mitigating the pervasive “landscape of fear” caused by human presence is crucial, not only for conserving wildlife populations, but also for preserving the delicate balance of ecosystems that our own survival depends upon.

References

Allen MC, Clinchy, M & Zanette, LY (2022). Fear of predators in free-living wildlife reduces population growth over generations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119: e2112404119.

Darimont CT et al (2023). Humanity’s diverse predatory niche and its ecological consequences. Communications Biology 6: 609.

Green RJ & Higginbottom, K (2000). The effects of non-consumptive wildlife tourism on free-ranging wildlife: a review. Pacific Conservation Biology 6: 183-197.

Stronza AL, Hunt, CA & Fitzgerald, LA (2019). Ecotourism for conservation? Annual Review of Environment and Resources 44: 229-253.

Laundre J, Hernández, L & Ripple, W (2010). The landscape of fear: ecological implications of being afraid. The Open Ecology Journal 3: 1-7.

Valeix M et al (2009). Does the risk of encountering lions influence African herbivore behaviour at waterholes? Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 63: 1483-1494.

Whittaker D & Knight, RL (1998). Understanding wildlife responses to humans. Wildlife Society Bulletin 26: 312-317.

Yovovich V, Thomsen, M & Wilmers, CC (2021). Pumas’ fear of humans precipitates changes in plant architecture. Ecosphere 12: e03309.

Zanette LY & Clinchy, M (2020). Ecology and neurobiology of fear in free-living wildlife. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 51: 297-318.

Zanette LY et al (2023). Fear of the human “super predator” pervades the South African savanna. Current Biology 33: 4689-4696.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Salvador Herrando-Pérez is a scientist with a strong interest in biodiversity data curation and global change ecology. He holds a PhD in ecology and currently serves as Science Lab Manager for the Miguel Araújo Lab (Spanish National Research Council, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC), where he supports research on species distributions and climate impacts. He is currently investigating the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna through fossil dating. His career bridges quantitative ecological research with a passion for communicating science to wider audiences.

|