Several communities all over the world have placed signs forbidding drones from flying over certain zones. They may stop amateur drones, but not military ones. The problem with drones as weapons is that they are so cheap. And when something becomes cheap, you can have more of it; it is a basic principle of economics.

Why we Need a Peace Offensive

Do you remember Tennyson’s poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade”? It was written in 1864, during the Crimean War, and included the line: “Theirs not to make reply, theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do and die.” Today, we tend to see the charge of the 600 in Balaclava as an example of military stupidity. But Tennyson meant exactly what he said; for him, the cavalrymen who blindly charged the Russian artillery were an example to be followed. Everywhere, soldiers were supposed to behave as robots (or “drones”), an idea that remained entrenched in military thinking up to recent times. But today, you don’t need to struggle to turn human beings into drones; you can have the real thing. Military drones are becoming the main war weapons, and soon they will be the only ones.

It is well known that technology affects politics much more than politics affects technology. It was with this principle in mind that, in 2012, I wrote a chapter on the effect of drone technologies on war for the book edited by Jorgen Randers, “2052.” More than 10 years later, I see that it was an easy prediction to state that drones would soon make human soldiers as obsolete as war elephants after Hannibal. But the main point of my essay was not that. It was about the political. spocial, and economic changes that drones would bring.

Adam Smith famously said that, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner.” He meant that the butcher expects to be paid in a peaceful exchange, but it is also true that, in some conditions, customers may be tempted to get their steaks by shooting the butcher dead. It may happen when, for instance, an economic or social collapse makes it impossible to maintain structures such as a functioning police or a stable currency. And we can cite Bug’s Bunny: “This means war!”

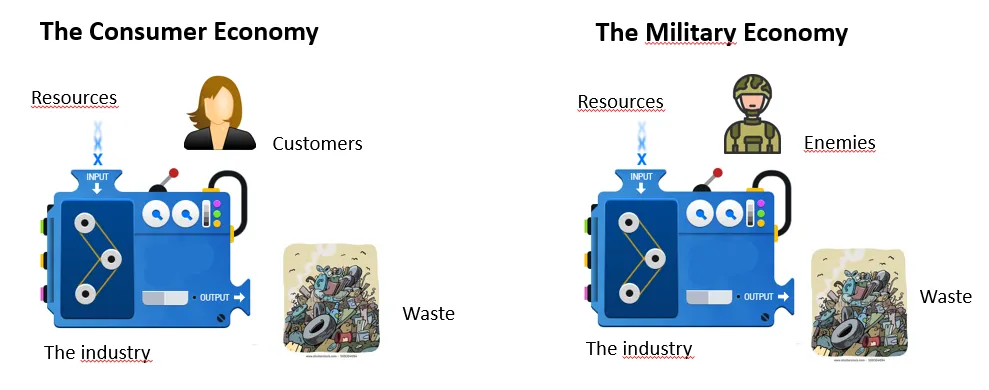

All wars are resource-allocation tools and we could say, paraphrasing Clausewitz, that they are a continuation of the economy by other means. The difference is that we tend to see the economy as based on monetary exchanges in a free market. With war, instead, resources are allocated by violence, as I discussed in a previous post.

Illustation provided by the author. Click on the image to enlarge.

What we are seeing today at the international level is the convergence of two factors that are creating a new violence-based global resource allocation system. In part, it is due to the decline of government structures of all kinds, but another factor is that Drones have made wars cheap.

During the past few centuries, wars evolved into expensive and bloody affairs that involved masses of infantrymen. Fielding millions of soldiers was not just a heavy cost in itself. It required a massive propaganda effort designed to convince the conscripts that it was a good thing for them to become cannon fodder. It worked but, once started, this kind of propaganda fed on itself and couldn’t be stopped. A major war could only end when the economy of one of the states involved was completely wrecked by the war effort. Expensive, indeed, for both the losers and the winners, considering that sacking a bombed country doesn’t even repay the cost of the bombs.

The huge cost of wars has been part of the general perception of international affairs up to now. It may be for this reason that, during the past 80 years or so, we haven’t seen major powers warring against each other. Nuclear weapons didn’t change the equation. Even though they are cheap in terms of kills per dollar, they destroy everything and leave nothing for the winners to sack.

Today, however, drones are changing the picture and governments don’t need to send a large fraction of their citizens to be butchered in humid trenches anymore. That means an enormous cost reduction. And we know what the effect will be: Drones making wars cheaper means that we’ll have more of them (both drones and wars). And that explains much of what we are seeing nowadays, with wars erupting everywhere. Although we are told mostly about drones in the military operations in the Donbass, they are enthusiastically used everywhere in local wars.

The changes brought by drones go deeper than just making wars cheaper and more frequent. I argued in 2012 that this evolution need not be a bad thing in itself; it could turn wars from an exercise in people slaughtering into a sort of spectator sport with robots engaged in wrecking each other. You may have seen the popular UK TV series “Robot Wars.” It demonstrated that people can cheer for robots just as they do for their local soccer team. If that were the future, violence against humans would be reduced.

Unfortunately, there is a problem with this idea. Unlike the clumsy robots of a TV show, real drones kill people; it is the main purpose they are built for. Unlike nuclear weapons, they kill without damaging infrastructure. Unlike biological weapons, they can be directed against specific human targets, defined, for instance, by skin color or other physical characteristics. Unlike fanatics armed with machetes or explosive belts, they can be controlled and stopped whenever needed. Unlike starving people to death, they don’t generate pictures of malnourished children begging for food. In short, they are the perfect human extermination machine. (a point that I also discuss in my book “Exterminations” (2024).

And here is the central point of the question: who controls military robots? They are not affected by patriotic feelings, not by ethical feelings, and they don’t care about opinion polls or about how many votes the current leaders managed to obtain, steal, or create. In the end, they are controlled by specialists who are likely to be more sensitive to money than to slogans. It means that the people who control money, control the robots.

It is a situation that, as I noted in my 2012 paper, is similar to that in Europe during late Medieval and early Modern Times, when war was waged mainly by “companies of adventure,” mercenaries who could operate the sophisticated weaponry of their age. Mercenaries gobbled up a large fraction of the states’ wealth; they were difficult to control, and they often revolted against their employers.

Something similar may be in store for us in the near future. Most of us who are not on the payroll of the military industry would like to see our tax money used for social security, health care, pollution control, and the like. But the military industry has much more clout than we do when it comes to paying government officials to favor a sector of the economy rather than another. See the latest decisions of the European Governments to direct a significant fraction of the member states’ budget to a military buildup. We “the people” were not consulted. We have no power to influence this decision, apart from a chance someday to mark a cross on one or another place on a ballot. It may be counted or not, but even if it were, it would have no effect.

From a rational viewpoint, what we are seeing is a terrible misallocation of resources: how can it be that our society is spending its resources on machines designed to kill people, when these same resources would be desperately needed to avoid the several impending disasters, from global warming to resource depletion? But all that’s happening has a logic. There is no overarching control of the complex system we call “society.” It tends to evolve through the interplay of internal factors. Darwinian selection is at play, but the main factor is cost. More complex control structures are also more expensive; hence, different structures may appear as a function of what society can afford.

The simplest kind of economy is one where the actors involved do not interact with each other at all. It is a zero-cost economy that we could define as the “Grab what you can, when you can” system. It corresponds to Garrett Hardin’s model of the “Tragedy of the Commons,” where individual gain optimization leads to a disaster for the community. One step above in complexity, there is the “robber economy,” where the economic actors exchange goods using violence; non-human social species are often at this level. Take one step up in the ladder, and you have an economy based on money, which is the one theorized by economists. Only human beings use this method, although our bonobo cousins may use sex instead of money to exchange goods (humans do that, too). Climb up one more step, and you have the rule-based economy. That is, an economy where economic exchanges are regulated not just by money, but by customs, social structures, and laws that protect the weaker actors and avoid such things as the overexploitation of resources. Elinor Ostrom showed how customs and laws can avoid the “tragedy of the commons.” There may be a higher stage where resource allocation is regulated by benevolence rather than by money, but humans don’t seem to be able to arrive at that level, except occasionally.

Societies operate according to one or another of these systems, depending on a balance of costs and benefits. From our human viewpoint, a rule-based economy is the one that brings the highest benefits to the largest number of people. It is, theoretically, the way modern states are organized. But it is an expensive arrangement, and society may slide down to lower levels as a result of the double whammy of services becoming more expensive and wars becoming cheaper.

In Argentina, President Milei loves to be pictured while holding a chainsaw to destroy the welfare state. That is, of course, only a symbolic tool. Military drones, instead, could be a real-world tool for the same purpose. Not necessarily because they will be used to exterminate the poor (although they may be; actually, they are already), but because they make it more attractive to jump back to a violence-based economy.

We are in a difficult situation (said the guy facing the tsunami with a teaspoon in hand). But never forget that the future is never fixed, and it always brings surprises. As I was saying at the beginning of this post, politics is affected by technology much more than technology is affected by politics, and new technologies may change the rules of the game. For instance, the development of artificial intelligence could allow us to dismantle useless infrastructures (e.g., universities) and streamline inefficient and overburdened bureaucracies while maintaining the services they provide. That could allow society to concentrate its remaining resources on vital services, such as the health care system or the social security for the elderly and the needy. In addition, the impending end of the global population growth, which has already occurred in industrialized countries, promises to ease many problems. [1]

Focusing on maintaining the essence of a rule-based society will not occur automatically. It needs an effort. One step in that direction is the concept of the “Peace Offensive” created by Donato Kiniger Passigli in 2024. It is a proactive attempt to build community and to fight for human rights in the name of our common heritage of human beings. Can it be done? It is not impossible, and there are ongoing efforts to restore the rule of law in a world that seems to have completely forgotten it.[2]

The Roman Empire found itself in a similar quandary during its declining phase, and Empress Galla Placidia understood the need to rein in the warlords of the time, including the all-powerful emperors. She enacted the “Digna Vox” edict in the name of her son, Valentinianus, restoring the rule of law in the empire. We should try to do something similar.

Digna vox maiestate regnantis legibus alligatum se principem profiteri: adeo de auctoritate iuris nostra pendet auctoritas. Et re vera maius imperio est submittere legibus principatum. et oraculo praesentis edicti quod nobis licere non patimur indicamus.It is a statement worthy of the majesty of a reigning prince for him to profess to be subject to the laws; for our authority is dependent upon that of the law. And, indeed, it is the greatest attribute of imperial power for the sovereign to be subject to the laws. By this present edict we forbid others to do what we do not permit ourselves.

Imperatores Theodosius, Valentinianus - 429 AD

Notes

[1] On this point, see my impending book: “The End of Population Growth”, available probably in October.

[2] See also an organization trying to stop the drones: https://www.stopkillerrobots.org/.

By the same author:

Putin and Trump Meet, but the Bombers Set the Agenda

Farewell to Grok