“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach him how to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” The Western-led international development sector, born in the aftermath of World War II, has evolved according to this (ironically) Chinese proverb. To better reflect the status of international development, I would append the following sentences to the worn-out proverb: “Use advanced extractive technology to harvest all the fish from the man’s ocean, and you solidify a power imbalance that is favorable to you for generations. To cover your tracks, tell everyone that the man’s chronic lack of fish is despite your involvement, not because of it.”

I’ve spent most of my career in international development, which the United Nations (UN) defines as “a multidimensional undertaking to achieve a higher quality of life for all people.” I volunteered in Peace Corps Panama’s sustainable agriculture sector, studied global affairs with a concentration in sustainable development, and worked at an international food policy think tank in DC. The impressions I share here do not reflect every individual and institution in the international development sector.

Let’s imagine international development as a coin resting on the iconic marble podium at the UN General Assembly Hall. The upturned coin face paints a picture of the millions of people who don’t have enough to eat, who lack basic sanitation infrastructure, and whose societies are riddled with corruption and violence. Its imperative is to provide aid and “accompaniment” so that those with less—less money, less information, less democracy—can have more.

But there is another side to this coin.

The Famine and the Feast

The other side rarely sees the light of day, at least in forums where high-income countries (HICs) set the agenda (I distinguish between those who consume more than their fair share and those who consume less with the unsatisfactory HIC and LMIC (low- and middle-income country) labels). It paints a picture of millions of people feasting on the fruits of colonization, slavery, and economic manipulation. They are either ignorant of or apathetic to the associated devastation, which often unfolds in far-off lands. This downturned coin face provides an imperative for those with more to do less: consume less, produce less, manipulate less.

Critical to our interpretation of this picture of feasting people is the acknowledgment that it resides on the same coin as the picture of starving people. Many people are aware of both pictures but see them on two separate coins. Their imperative is to transfer people from the starving coin to the feasting coin. They see the feasting coin as the gold standard of development.

The reality is that the feast and the famine are inextricably and causally linked; the famine exists not despite the feast but because of it. This is especially evident as humanity approaches limits to growth on a finite earth.

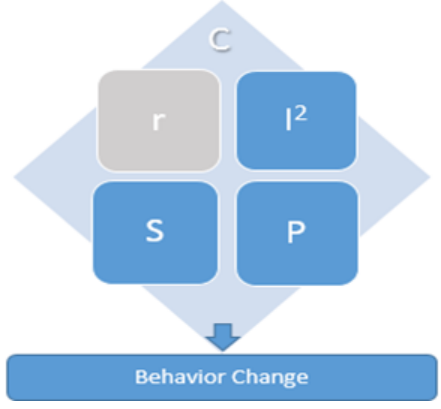

Behavior Change

A glimpse at the World Bank’s approach to behavior change. CrI2SP = Communication, resources, Incentives and Information, Social Factors, and Psychological Factors. Source: World Bank's Independent Evaluation Group. Click the image to enlarge.

|

“In effect, all development interventions presume behavior change.” This is a quote from the World Bank Independent Evaluation Group’s framework for evaluating behavior change. It aligns with my experience in the sector, where my work often aimed to change the behavior of small-scale farmers. The goal was for project “beneficiaries” to change from one planting, harvesting, or marketing behavior to another. Experts had deemed the introduced behavior superior in some way; typically more profitable, sometimes more sustainable.

These initiatives often took the Chinese proverb a step further than teaching a man how to fish, by teaching a man (or even a woman!) to teach others to fish. This is an improvement from the “Washington Consensus” style of development that a) forces LMICs to undergo structural adjustments in exchange for loans that trap them in cycles of debt and b) dumps artificially cheap commodities from HICs onto LMIC markets, often driving local producers out of existence.

Even evolved development institutions hang on a common thread running throughout the sector’s history: LMICs need change. Some development practitioners view people in poverty as active agents that must create change. Some have the less-becoming (and often subconscious) perception of people in need as passive objects that must receive change. Regardless, the spotlight is on those with less (less money, to be precise).

I would be remiss not to mention the international development sector’s incredible strides. For example, the world looked poised to eliminate hunger when the prevalence of undernourishment dropped from thirteen percent in the early 2000s to seven percent in 2017. Yet the eradication of societal ills such as hunger remains out of reach. In many cases, progress has stalled and even reversed (undernourishment has increased to nine percent). And while the sector has been occupied with “traditional” development issues (hunger, communicable disease, etc.), noncommunicable diseases (heart disease, stroke, etc.) have become the leading cause of death worldwide. They are taking an especially heavy toll on LMICs.

What if LMICs can’t overcome these obstacles by changing solely their behavior? This is a question I asked myself in Peace Corps, when a massive flood, the likes of which had become more frequent, wiped out the crops of the Indigenous farming community where I lived. What if everyone in the community adopted the climate-smart agriculture techniques I was there to promote? Would that be enough to overcome the worst effects of climate change, on the tired and infertile land European colonizers had squeezed them onto? Perhaps someone else’s behavior needs to change…

The Gold Standard, or the Root Problem?

Most development practitioners are keenly aware that HICs’ historic oppression of LMICs, via colonization and slavery, set present-day inequalities into motion. Many are also cognizant that this exploitation has continued in the form of “neo-colonialism.” Some, such as dependency theorists, recognize the two-faced nature of the development coin. They argue that HICs are “developed” precisely because they exploit LMICs. (A reminder here of the lack of nuance that “HIC” and “LMIC” provide. Not everyone in HICs has benefited from this exploitation, and many in LMICs have partaken in it.)

However, the mainstream international development sector fails to acknowledge the systemic nature of this ongoing exploitative relationship. The culture of domination, consumption, and growth that motivated colonization and slavery is thoroughly baked in. It’s reflected equally in the belligerent expansion of multinational corporations and the reckless consumption of goods and services by the average HIC household.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) demonstrate this insufficient acknowledgment of the need for HIC behavior change. All UN Member States adopted these 17 goals in 2015. Countries were assigned scores in 2024 based on their percentage of SDG achievement. Presumably, the country with the highest SDG score is the most “sustainably” developed. It sets an example toward which the development sector should strive. With the exceptions of Japan and Canada, the 25 highest SDG scores all belong to European countries. Finland ranks first, having achieved 86% of the SDGs.

Several of the SDGs are explicitly environmental, yet the most unsustainable societies score relatively high. Source: United Nations. Click on the image to enlarge.

|

Would the world be a better place if every country behaved like Finland, where no one lives below the international poverty line? The answer is emphatically no, at least not in the long term. Finland’s ecological footprint per capita is 5.2 global hectares. In other words, a Finn’s lifestyle requires 5.2 hectares of biologically productive land and water. If everyone behaved that way, we would need 3.25 Earths!

If everyone adopted them, the earth could not support the lifestyles of any of the 25 countries with the highest SDG scores. It becomes even more problematic to put Finland on a pedestal if we consider the country’s path to reach its current wealth. Finland used to be part of the Swedish Realm, which established colonies in Africa and North America. In modern-day colonial fashion, Finnish company Stora Enso has been involved in multiple land grabs.

And many of the high-scoring European countries are far worse than Finland. Denmark, with the third-highest SDG score, has an ecological footprint per capita of 7.3 global hectares. That’s 4.6 times the earth’s sustainable and equitable limit. Footprints don’t get that big without some colonial supplementation. The United Kingdom is the world’s biggest colonizer, with a historic total of 115 colonies, by some accounts. It ranks ninth in SDG score. France (53 colonies) and Portugal (52 colonies) rank fifth and sixteenth, respectively.

Ecological Economics for International Development

In LMICs, a lack of resources (represented by money) is often the biggest barrier to change. The type of behavior change that needs to take place in HICs is difficult for the opposite reason. HIC economies are too big; too much domestic consumption drives too much extraction around the world. All this economic activity leads to too much money, and money equals power. This power is directed at ensuring the economic machine keeps chugging. Not just chugging, but growing.

Indigenous Honduran activist Berta Cáceres was murdered for her opposition to a hydroelectric dam. The project had many international funders, including the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation. Source: Wikimedia. Click the image to enlarge.

|

To ensure this growth, money-power is wielded to disempower the people whose resources are needed for ever-growing supply (LMICs). It is also used to indoctrinate with consumerism and complacency the people whose minds are needed for ever-growing demand (HICs). Many in international development and adjacent fields are fighting the supply side of money-power, whether they frame it that way or not. Development and activist organizations work to establish and protect locals’ rights to land and other natural resources.

There is also a slew of actors fighting money-power within HICs, from anti-trust lawyers to minimalists. They work to stop the establishment of corporate monopolies, expose corporate capture of political actors, curb extreme wealth, and raise awareness of the causes and consequences of consumerism. These actors are not typically considered part of the international development sector.

Both camps—those working to improve well-being in LMICs and those fighting the economic growth machine in HICs—may be more successful if they come to see their work as two sides of the same global coin. This could open doors for pivotal collaborations and new, more holistic understandings of systemic issues.

I posit that ecological economics is an ideal counterpart to those working toward change in LMICs, because it approaches HIC behavior change from the angles of macroeconomics, policy, and sustainability. Adjacent to ecological economics, which advocates for a steady state economy, are movements such as degrowth, postdevelopment, and doughnut economics. These movements are motivated by an understanding of limits to growth on Earth, our shared home. With environmental justice as a central tenet, they advocate for decreased resource use in HICs to create some breathing room for LMICs to “develop” as they see fit.

The policies that spring from ecological economics aim to reduce wealth inequality, via salary and luxury caps; to regulate advertisements for Earth-damaging products; and to reduce the workweek to alleviate employment pressures (to name a few). It doesn’t sound like international development, but it’s a key dimension of the “multidimensional undertaking to achieve a higher quality of life for all people.”

Food for Thought for Development Professionals

I am by no means suggesting that international development funds should be siphoned off and redirected toward HIC behavior change. This has happened in the world of climate policy, where the need for behavior change in HICs has been widely recognized as “mitigation.” Mitigation has been pitted against adaptation, and funds sorely needed to adapt to a changing climate in LMICs are spent instead on the renewables transition in HICs. In 2021-2022, $1.2 trillion was spent on mitigation and $63 billion was spent on adaptation annually. The share of climate finance dedicated to adaptation (5%) has only decreased.

This is a tragic missed opportunity to model complementary initiatives for behavior change in HICs and LMICs. HICS must transition to renewables, and doing so will cost money, but they also must consume less energy. This is true for the larger behavioral shift HICs must undergo: a transition to less, not more.

At the individual and institutional levels, the international development sector should flip the coin over once in a while. If you work in the sector (especially if you’re from an HIC), ask yourself who set the goals you’re working toward and what success would look like. What ideologies are you leveraging to reach your goals? What behaviors would need to change in HICs to reach those goals? Who knows, you might even strike up a partnership with an ecological economist.