Our new technologies are grafted onto rotten roots.

--Mattern (2021)

The lords of Silicon Valley are all done with earthly reality.

--Zickgraf (2021)

What can be said about globalized tech when our earthly existence is consumed by viral uncertainties, urgent climatic shifts, and perpetual socio-environmental precarity and violence? How are we to understand earthbound politics amidst the hyper-expansion of technocapital financialization, electronics consumption, digitized social activism on a global scale, and Big Tech intrusion and take-over in almost every sector of business, education, healthcare delivery, supply-chain infrastructures, etc.? What connects racial and digital capitalism to the global political ecology of technology? What happens to our social worlds when technologies (and surveillance tech creep) flourish amidst global democratic collapse and planetary crisis? These are the centering questions guiding my newest book Critical Zones of Technopower and Global Political Ecology: Platforms, Pathologies, and Plunder (Lexington Books, 2023). The book doesn’t claim to offer simple or clean answers to these critical questions. Instead, it provides a complex navigation of these and other inquiries about a technocapitalized world that calls for deeper, more intersectional, perspectives on political-ecological relations and just tech politics of care and repair. More “recycling” won’t work in a world of tech production cycles of production that always outpace green recycling efforts. Real change will certainly require new—and more radical—forms of care and repair.

Motherboard Discard in Ghana. Photo by the author.

Click the image to enlarge.

As technology critique Manuel Castells highlighted in his lengthy information age intervention (Castells 1996), we know for sure that technologies have generated “permanent change,” as he put it. A political ecology of tech, as I develop in Critical Zones of Technopower and Global Political Ecology, suggests such change is truly a complex mixture of social, political, economic, and ecological transformations that are increasingly overlapping. Today, we can’t really uncouple political economy and environmental transformation from globalized technologies. The actual technological proliferation and Big Tech dominance we are witnessing today is radically intensifying this eco-tech coupling and intersectionality. Furthermore, tech is now a central subject in global policy discussions of inequality. The so-called “megatrends of inequality,” as the United Nations reported in 2020, involve technological innovation, along with other global trends like climate change, urbanization, and international migration. According to the same UN report, “Technological change can be an engine of economic growth, offering new possibilities in health care, education, communication and productivity. But it can also exacerbate wage inequality and displace workers” (United Nations 2020:2). Even “just” energy transition advocates and “green New Deal” enthusiasts note that structural changes have long proved to have serious downsides, noting that “[p]revious transitions to coal and oil deepened imperialism and racial capitalism” (Aronoff et al 2019:156). With “technology” most often conceptualized as simply a “tool” for even righteous just transitions, the problem is that tech can easily escape this critique. One dominant reason for this is because technological modernization is deeply fueled by the ethos of classical economic liberalism, which, among other characteristics, “has a fetish for spontaneity” (Ahmari 2023:136). For me, this is a root problem of technopower, especially if we commit to understanding tech as a political-ecological system informed by the intersectionality of social, political, economic, health, and environmental realities.

Critical Zones of Technopower and Global Political Ecology explores the infrastructures, ideologies, and consequences of technocapitalism and how technopower has actually penetrated planetary systems of trade and commerce, science and communication, education and healthcare, corporate plutocracy, and environmental transformation. Digital Age declarations are perhaps best understood as statements of juggernaut tech growth. In 2020, Big Tech profits soared to 2.7 trillion dollars, based on conservative estimates. Engaging this level of technopower, this book grapples with a meshwork of relations and forms of technological intersectionality emerging at the frontlines of a planetary and precarious life that now involves billions of machines, digital age things, and circuits of capital accumulation. It keeps a steady focus on a critical zone of planetary life where tech marvel and influence meets social, health, environmental, and political crisis and toxicity. This is the core tenant of the book and it uses anthropological insight to ground and contextualize the global North and South tensions and relations of globalized technopower and its’ tyrannical consequences.

Desktop “Cleanup” Message. Photo by the author.

Click the image to enlarge.

For me, the book dovetails closely with some of the counter-hegemonic and anti-patriarchy aims of Mother Pelican. A few intersecting threads come to mind. First, the book takes an explicit counter-hegemonic stance towards technocapitalism, but also attempts to ensure that this approach never looses sight of the ongoing uses of tech for counter-hegemonic politics. It doesn’t shy away from the elephant in the room, which is that tech has been used righteously in recent times to counter pathological hegemonic forces, like police brutality and unjust surveillance operations in zones of social protest and action. Second, the journal’s emphasis on rethinking the place and space of “solidarity” in various domains of socio-political critique also dovetails with the aims of the book. Through the lens of “solidarity” and radical care, the book navigates the critical role of “just tech” initiatives that are emerging in social and political life to actually resituate and reset the force of tech in social and environmental justice movements. One notable effort spearheaded by the Social Science Research Council is the “Just Tech program” which “foregrounds questions of power, justice, and the public impact of new technologies, investigating evidence of bias and harms while imagining and creating more just technological futures.” Such initiatives are starting to actively counter the political-ecological tyranny of tech, yet the work of radical care and solidarity is an ongoing process that calls for a broader vision and ecology of ideas, inputs, and interventions.

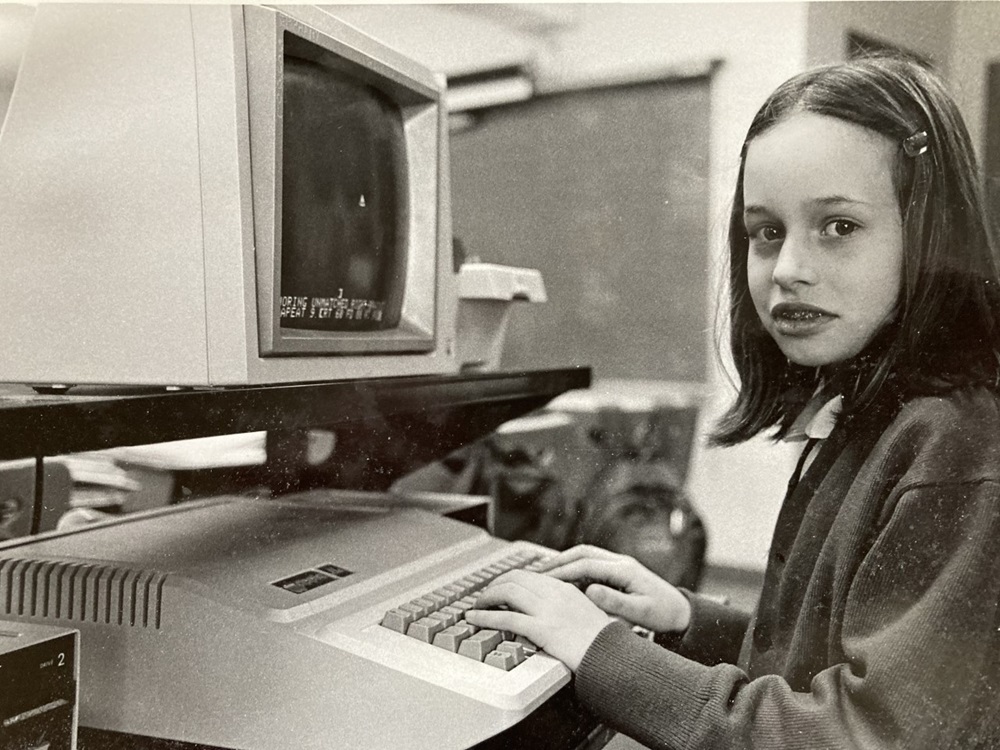

The Intentional Enculturation of Technopowered Learning. Photo by Anne Brewster.

Click the image to enlarge.

Finally, the computer revolution has been a deeply normalizing machine, a system to be inserted into all human systems—healthcare, government, education, etc.—and which also relies on processes of enculturation. The so-called “Computer Age” feeds on the young—indeed needs the young to create life-long users—and it is no mistake that the “motherboard” became the central focus of this expansionary operating system. Perhaps reimaging the materiality and cultural life of tech—and the motherboard—within the framework of Earthly solidarity and thriving might indeed call for more serious discussion to the actual “mothering” and “caring” of tech and the environmental politics of survival and solidarity that surround this ever-growing industry of the future. Forging a more radical reimagination of tech we will have to collectively learn anew, and perhaps spend even more energy and time unlearning what has become deemed necessary for living a life on this plundered and uncertain Earth of accumulating technologies and growing struggles of solidarity that aim to center the deeper value of radical care and repair.

References Cited

Ahmari, Sohrab. 2023. Tyranny, Inc.: How Private Power Crushed American Liberty—and What to Do About It. New York: Forum Books.

Aronoff, Kate, Alyssa Battistoni, Daniel Aldana Cohen, and Thea Riofrancos. 2019. A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal . London: Verso.

Castells, Manuel. 1996. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture . Vol. 1: The Network Society. Malden: Blackwell.

Mattern, Shannon. 2021. A City Is Not A Computer: Other Urban Intelligences . New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

United Nations. 2020. World Social Report 2020: Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World . Department of Economic and Social Affairs. ST/ESA/372. United Nations.

Zickgraf, Ryan. 2021. Mark Zuckerberger’s ‘Metaverse’ Is a Dystopian Nightmare. Jacobin. September 25.

|