1. Introduction

The fast-approaching 50th anniversary of the landmark Limits to Growth [1] provides an unparalleled opportunity for concerned energy and systems scholars to work toward renewing public and policy debate that would foster understanding about the impossibility of unending physical and economic growth on a finite planet. In lieu of a comprehensive review of relevant scholarship in diverse fields (a book-length undertaking in any case), this Perspective draws from first principles to offer a framework and calls for a transdisciplinary conversation founded on the centrality of energy flows through our open natural and social systems [2], [3].

Given overshoot of planetary limits in several important dimensions [4], humanity has no option but to learn how to power our world without ending it. While academics aware of the manifold intersections of energy and social systems are crucial to this undertaking, not enough seem committed to raising now necessary, serious questions about the nature and history of concepts, frameworks, and jargons in our various disciplines, given their development in the context of the last two centuries of anomalous fossil-fueled expansion. Disciplinary fragmentation and the dominance of analysis over synthesis has led the academy into a situation of knowing more and more about less and less [5].

2. The Past Is Not Prologue

A quick review of salient, more or less well-known trends is important to establish context for our call to transdisciplinary action—recognizing that high energy modernity faces an existential and epistemological predicament, not a set of problems to be solved [6].

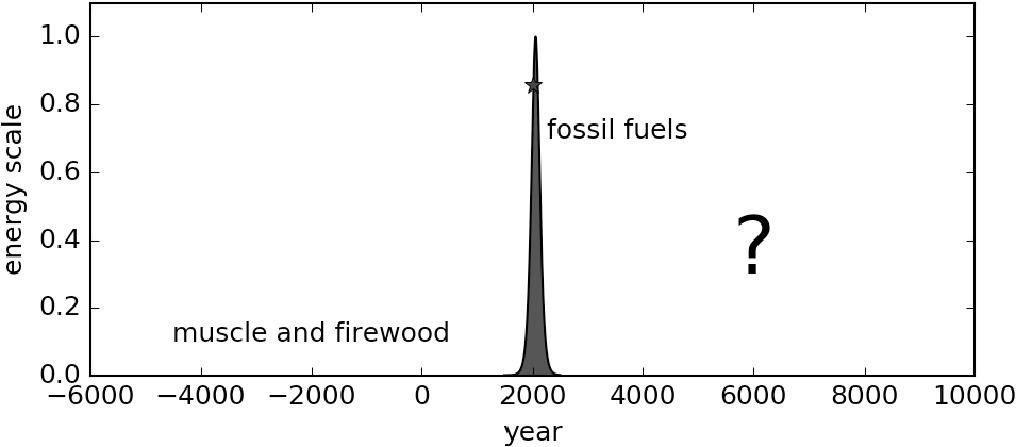

A plot of the rate at which human societies have extracted energy resources across history reveals the familiar “hockey stick curve” seen in numerous metrics characterizing human activity and associated ecological consequences. The curve is essentially invisible (near zero) at the bottom of the plot for thousands of years, dramatically rocketing upward in the last few centuries. In the foundational case of energy consumption, the recent steep rise is essentially a story of the discovery and use of fossil fuels: coal, petroleum, and natural gas to power industrial modernity. Today, these sources account for approximately 80% of energy production, and an even larger fraction in the transportation sector.

Yet fossil fuels—and other physical resources—are inarguably finite resources on this planet. Half of the economically viable conventional resources are likely spent, since we first harvested the low-hanging fruit and we are now extracting ever more challenging and costly deposits using advanced technology. In terms of now-dominant fossil fuels, the future beyond the hockey stick is easy to predict: fossil fuel use must fall back toward very low levels as abruptly as it rose [7]. On a few-century timescale, this one-time inheritance of fossil sunlight will be gone. Fig. 1 provides a striking visual, highlighting how unusual this period is on the scale of human history. It also ominously suggests that the future will not look much like the last century as the affordable fossil fuels that powered our current age are inevitably drawn down—though how, and how fast, the post-carbon transition may be expected to play out is the subject of fortunately growing, albeit contentious debate [8], [9], [10], [11].

Fig. 1. A schematic long view of human energy production rate up to the present (star), the dramatic rise of which is almost wholly due to fossil fuels, supplanting firewood and animate power (human and animal muscle) as primary energy sources.

Click the image to enlarge.

|

From this perspective, it seems likely that future generations will label the past two centuries as the Fossil Fuel Age rather than the Industrial Revolution—emphasizing the critical importance of a now-depleted resource over a self-flattering celebration of human innovation. Fig. 1 provokes potentially uncomfortable questions impacting all scholarly disciplines: What would a lower-fossil-energy future look like? Can an energy regime transformation take place as broadly and quickly as needed to offset declining net energy [12]? Is it as unlikely as preliminary studies suggest that renewable energy technology/innovation might save the modern human project from the challenges of a resource-constrained future [13]? Will the future look more like the distant past than the present? When does the downward portion of the fossil fuel age begin? What can be done to minimize the chances of colossal failure or sub-systemic breakdown, which in the worst case could threaten preservation of science and human knowledge? Certainly, failure to acknowledge dire possibilities invites huge risk. Much is at stake, and humanity must be very cautious about the temptation for denial, dismissal, or idolatrous hope for some technological breakthrough—especially in light of credible causes for concern.

It is not at all surprising that the toll of this production and consumption boom on natural systems has been high, showing myriad signs of strain on a global scale. The planet now hosts an unprecedented number of people, compounded by a relentless increase in the average human’s demand on resources (not even accounting for the vast inequities in the impact of different consumption levels). Manufactured materials last for centuries despite brief use, tossed aside in the “developed” world as if they vanish, only to have them reappear at someone else’s door, usually in the “developing” world. The globalized, full world affords no “away.” Fossil fuel use disregards the simple fact that they are finite and not renewable, confusing, in the words of E.F. Schumacher, “capital for income” [14]. Humans seem to have forgotten, as Ken Boulding noted in his famous metaphor, that we are on “Spaceship Earth,” and, now, one that is increasingly full of people and pollution, and that has a diminishing supply of the energy source that has powered modernity [15].

While energy is fundamental to the human story, it is not the only facet of concern. Others include: global food supply dependent on fertilizer from a finite supply of natural gas; escalating biodiversity loss, due largely to habitat losses [16]; domino collapse of one fishery after another [17]; aquifer depletion [18], [19], [20]; global warming’s ills (fires, floods, storms, desertification, sea level rise, etc.) [21]; and global pandemics—to name just a few.

Yet, again, this list is less a set of problems to be solved, than an unprecedented predicament to be understood and mitigated [6]. This is not a normal time. Faith in humanity’s future overlooks the lack of any historical evidence that human societies are capable of addressing such a litany of unfamiliar global-scale interconnected foundational problems. Notwithstanding various pre-fossil fuel age traditions that privilege longer term thinking (e.g., to the seventh generation), evolution and modern economics have acted on the human species to steeply discount the future in favor of the present [22]. The existential threats to Earth’s ecosystem posed by modern lifestyles require a response for which evolution has not prepared the human species: to think more than one generation ahead.

Modern industrial humanity is effectively hurtling forward in a giant unauthorized experiment lacking a coherent design or strategy, which worked well enough on a non-human-dominated planet. At present, democracies, markets, and a handful of authoritarian regimes are making the rules—largely uncoordinated, sometimes incompatible, and absent explicit reference to principles commensurate with a finite planet. Rather, decisions are dominated by short-term financial considerations that do not reflect biophysical realities or prioritize long-term sustainability. Norms and values, and the moral and ethical systems in which they are embedded, may have acted to curtail such unbridled self-interest in the past, but do not seem powerful enough today. Individuals and corporations do things because they can right now, without asking if they should, or what negative impacts may result decades hence. Given the ineluctably ethical nature of this predicament, robust collaboration among scholars in the humanities as well as the social and natural sciences is critically overdue.

So what is the problem? The seemingly successful approach thus far has produced many laudable feats to celebrate. Millions if not billions today enjoy lifestyles better than royalty of yesteryear could have imagined. The natural collective impulse is to avoid anything resembling a return to past ways; each actor wants a share of the big pie. An important recognition is that nature is indifferent to human dreams. Imagining or wishing for a particular future does not guarantee that such a future will be compatible with the biophysical world.

3. A Macroscopic View

Many thousands of planets around other stars have been discovered in the last few decades [23], [24], meaning that planetary systems are now understood to be common within our galaxy. Yet so far no close analogues to Earth have been found among these thousands (in part due to measurement challenges). And even if a handful of theoretically habitable but inaccessible planets were to be found tens of light-years away, it would not relieve pressure on humanity to live within the limits imposed by this finite planet, given timescales and the unimaginable energetic impracticality of space colonization (realities that the entertainment industry and some billionaires/enthusiasts habitually ignore).

To help illustrate this point, if the Sun is represented as a ~1 cm chickpea, Earth is about one meter away and a barely-visible speck roughly the diameter of a human hair. The Moon—the farthest that humans have traveled from Earth’s surface—is an even smaller speck and about 2.5 mm away from the Earth-speck. The inhospitable brick named Mars is on average 600 times as far as the Moon (1.5 m), and the closest star would be another chickpea about 300 km away. Space-faring fantasies have no place in confronting present challenges. Earth, humanity’s home, is the only option.

By any measure, the biosphere of Earth represents a staggeringly small fraction of the Universe—a perception that was driven home 50 years ago during the first voyages to the Moon, which revealed a delicately thin shell of blue air around a diminishingly small blue planet. Estimates put all biomass at about 2 trillion tons (including water content), and if that were spread uniformly across the Earth’s surface it would stack to a height of 4 mm; a delicate gossamer film across planet Earth. Life on this planet is indeed thin and precious.

As a result of billions of years of evolution, Earth has developed an exceedingly complex set of interdependent ecosystems, responsible for maintaining a breathable atmosphere, drinkable water, and sustenance for all species. Essentially all of humanity’s religious, indigenous, and spiritual traditions recognize and value this. Images of a barren Mars from Perseverance remind us what it would cost, monetarily, for humans to build such a system from scratch (i.e., starting with a sterile planet)—assuming we had the intellectual standing and wherewithal to do so. The figure might well run into the quadrillions or quintillions of dollars, if not unimaginably more. Just how much value did humanity inherit in Earth’s abundant provision? Presumably, the amount absolutely dwarfs today’s trillion-dollar economic scales. Yet society continues to place essentially zero economic value on this foundation despite the fact that it took billions of years to produce. Somewhat like a parasite, the comparatively minuscule-scale economy cannot survive without a functional ecosystem on Earth. Decisions should, therefore, place appropriate value on the real treasure—the gift of a working life-support system—and society should be prepared to accept substantially higher “costs” in today’s economic terms since global-scale ecological health is at stake.

But humans are wired to care about tradeoffs in the “big now”—exemplified by the concept of a discount rate reducing future value to zero—not wired to seriously contemplate and appreciate ecological health or the one-time fossil-fuel bonanza. Compared to the billions of years it took to build the present Earth ecosystem, humans have seriously, and perhaps inalterably, damaged it in a century or two. Humankind’s recent launch into modernity is like a first-time skydive: thrilling, and quite unlike anything that has come before, but now is the time to start asking if a parachute is at hand. Nature does not guarantee that a soft landing is in store. While Meadows et al. [1] were prescient, and while several scholars have since traced valuable major outlines of likely trajectories ahead [25], [26], [27], [28], no one on the planet can credibly paint an accurate and confident view of the state of humanity even 50 years hence. Our ability to scientifically manage a descent from the heights of fossil-fueled modernity is limited. Rather, the present trajectory of modernity should be viewed with tremendous suspicion, humility, and concern; the past offers little guidance. It seems clear to the authors that given the unprecedented scale of current global pressures on many fronts, if these facts are not soberly and proactively engaged, then the modern human experiment will surely fail.

4. The Growth Collision

Simply stated, people want (and are encouraged to want) goods and services beyond their base needs, and markets are happy to oblige. A common recipe for countries to achieve high standards of living has been the combination of democracy and capitalism. For the most part, people vote for policies that will improve their circumstances, and corporations make decisions aimed at maximizing profits/growth. Politicians and financiers celebrate strong growth numbers (grumbling only when an over-heated market might signal runaway inflation), while bemoaning weak quarters, and practically panicking at the prospect of a recessionary period. Today the financialized capitalist economic system dominating human activity is predicated on growth and the expectation of a bigger future, witnessed in interest rates, loans, investments, massive public and private debt, and the outsized role of the banking system. Growth is thought to be such an unarguable good that the UN’s 2015 Sustainable Development Goal #8 actually calls for growth rates of 7% in less developed countries [29]. While this rate is intended to address the inequitable distribution of wealth across nations, the goal is still based on a business-as-usual, fossil-fuel-based economy.

Yet built-in conflict looms. Growth, both material and economic, simply cannot continue indefinitely on a finite planet. Economists—supported by only a short period of empirical evidence—have argued that substitution and decoupling are mechanisms that can allow for indefinite growth. Plenty of examples from the past bolster such arguments. On substitution, the Stone Age did not end due to a lack of stones, one pithy argument goes. On decoupling, trading fine art has a tiny energy-to-monetary ratio. But the overall evidence does not support the idea that the basic operation of the modern economy can happen without massive material and energy throughput [30]. In practice, efficiency gains are largely erased by further growth [31]. Remember that all such past examples from the industrial era have taken place in the context of unsustainable exploitation of finite resources. The future need not look like the recent past—in fact, cumulative irreversible impacts mean that it can’t.

This is such an important core argument that it bears elaboration. First, consider the story of energy usage in the United States over the last two hundred years. The trend closely follows a constant growth rate of roughly 2.4% per year for this entire period [32], conveniently corresponding to an increase by roughly a factor of 10 every century. Applying this rate to today’s global energy production rate of 18 TW suggests that humanity’s energy usage would exceed the output of the entire Sun in 1300 years and all 100 billion stars in the Milky Way Galaxy within 2400 years. Continuing such a few-percent annual energy growth is clearly not possible for very long on civilization-relevant timescales.

Thinking about it another way, energy processes on Earth produce heat that must be radiated to space—the only significant cooling channel. No matter what the technology—even allowing hypothetical, undiscovered energy resources—the Stefan-Boltzmann Law in physics prescribes the equilibrium temperature of the planet’s surface as a function of power produced. At a continued 2.4% annual increase in power production, the surface of the Earth reaches boiling temperatures in about 400 years and reaches the surface temperature of the Sun within 1000 years. These numbers—which dwarf the CO2-driven global warming effect—are clearly absurd, shutting down any notion that the energy growth experienced these last few hundred years can be expected to continue apace for hundreds more.

But why should cessation of growth in energy consumption spell an end to economic growth? After all, not all economic activity is energy-intensive (the idea of decoupling, as noted above). But some activities will always be energy intensive: boiling water and other thermal tasks; fertilizing and harvesting food; smelting aluminum and other materials processes; and transporting people and goods. Many of these are non-negotiable staples of human activity, and will be capped at a maximum scale by the facts elucidated in the foregoing arguments. In turn, the fraction of the “decoupled” economy—goods/services of intangible or aesthetic value, for instance—must remain modest, lest the essential survival elements be relegated to a negligible (therefore arbitrarily cheap) fraction of the economic scene—counter to supply/demand pressures [33]. Human culture—people’s values, beliefs, and attitudes—is complexly interwoven in these energy-driven transitions [34].

5. The Road to Crisis

The fossil fuel revolution changed major features of industrializing societies, having important cultural effects, including in most fields across the academic landscape [35]. Anthropology, sociology and allied fields, for example, developed during the coal-fired nineteenth century when evolutionism meshed with European-centered colonialist projects in a triumphant narrative of secular progress: one that periodized human cultures in an ascending sequence of historical stages from a hunter-gatherer deep past through an intermediate horticultural and agricultural near-past to a privileged emerging industrialism [36]. These ideas live on in our fields, especially the social sciences, for example in a still regnant division between “first/developed” and “third/developing” worlds that also informs diplomacy and foreign aid programs of the US and other developed nations.

These effects are especially well illustrated in the evolution of economics, a field that remains disturbingly resistant to the idea of limits to growth. Predating the field now called economics was classical political economy, whose major intellectuals (Smith, Ricardo, Malthus, and Mill) were broadly educated in the natural and social sciences. For them, the idea that economies could grow indefinitely was unthinkable because the economy was tied to a finite resource base:

It must always have been seen, more or less distinctly, by political economists, that the increase in wealth is not boundless; that at the end of what they term the progressive state lies the stationary state, that all progress in wealth is but a postponement of this, and that each step in advance is an approach to it. [37]

But exploitation of fossil fuels, technological change, and industrialization in general radically changed the productivity of resources, and therefore the way in which economists viewed the natural world, and more specifically, how the natural world related to economic growth. The “Marginalist Revolution” of the late 1870’s brought mathematical elegance to economic theory, however decontextualized, marking the transition from classical political economics to the neoclassical era. Smith’s The Wealth of Nations and Malthus’ An Essay on the Principle of Population were texts about how nations prosper (or not, in the case of Malthus) [38], [39]. By contrast, Walras’s Elements of Pure Economics brought forth general equilibrium theory, focusing on microeconomics [40]. Most importantly, the transition from classical to neoclassical economics was also a transition from an interdisciplinary, systemic view of how nations succeed (or do not succeed), to a narrower disciplinary view of how goods and services are produced at the margin [41]. Missing from the story are the larger biophysical and cultural contexts affecting how large a sustainable economy might be, as well as confusion over what “wealth” means—or even more surprisingly, how to measure it [42].

The increasing pace of industrialization and the vast discoveries of fossil fuels in the early 20th century only reinforced the importance of technology for neoclassical economists. It is difficult to overstate the abundance of resources during this period: when Spindletop was discovered in East Texas on January 10th, 1901, it gushed over 100,000 barrels of oil per day, a rate that exceeded half of the total U.S. oil production at the time. The next sixty years continued this trend, bringing one discovery after another before peaking in the 1960s.

In this era of resource abundance, fundamental differences between energy types, such as whether or not they are exhaustible, were not a central focus of economic literature. Economists began to think about economic growth as the result of a specific combination of “factors of production,” of which resources were only one, ever-less-important factor. Furthermore, neoclassical theory came to posit that factors of production are substitutable, meaning that via the miracle of free market dynamics any perceived shortages of one of these factors, including, for example, a non-renewable resource such as oil, could be offset by adopting a different resource—despite a finite menu represented by the Periodic Table. Economists misunderstood the importance of energy, saying it was not important because it was cheap (only 5% of GNP), when in fact energy was valuable precisely because it was cheap—a lot of work for relatively little money.

The neoclassical perspective toward growth and resources was formalized in Barnett and Morse’s 1963 Scarcity and Growth: The Economics of Natural Resource Availability, in which they claim that natural resource availability, or the lack of resource availability, will not constrain growth [43]. This view was epitomized by Robert M. Solow’s argument that “The world can, in effect, get along without natural resources, so exhaustion is just an event, not a catastrophe” [44]. This view seems to represent an especially egregious disconnect from physical reality.

The trajectory here is plain to see. In an empty, resource rich world, economic theories tend to think that growth will never be constrained by resource availability. But how can the same theory possibly apply in today’s resource-constrained and ecologically vulnerable world? The discovery and exploitation of fossil fuels, in other words, was a “rabbit out of the hat” game changer that twisted the narrative of modernity to cast this one-time windfall as normal and repeatable, counter to any evidence. Living up to the Homo sapiens moniker surely requires enough wisdom not to be tricked by this faulty logic [45].

Along with modern economists, corporations, politicians, and individual citizens are all complicit to some degree in this gross misunderstanding, since now virtually all humans are enmeshed in the late capitalist growth imperative. Today’s society has embraced growth so completely that the idea of a no-growth—or deliberately de-growth [46]—society is deeply unnerving and unthinkable to many. An important observation is that young children, independent of the circumstances of their birth—whether impoverished or extravagant—have no perspective other than to view their environment as normal. Only through adult eyes can they start to see how skewed their world may have been. Likewise, when generation after generation in modern societies have only known this brief, explosive period of human history, it becomes easy to appreciate how difficult it is to step back and entertain a broader view—especially when the content may not be pleasing. It is time, however, to view current neoclassical economic theory—indeed all the received knowledge in our various social science and other disciplines—through adult eyes and admit that growth is not only temporary, but ultimately may constitute an existential threat to human wellbeing. The situation calls to mind Walt Kelly’s “we have met the enemy, and he is us”—though costs and benefits are of course unevenly distributed in social space.

6. Moving Forward

To be clear, the authors are not making blanket statements about the pros and cons of markets, capitalism, socialism, or communism. (These are tasks for the scholarly network whose creation we urge.) Competition can exist without growth. Yet few have noticed or acknowledged the current collision course as a legitimate risk because of a “so far so good” attitude. It should therefore not be a surprise that at some point an increasingly “full world” [47] will transition from a state in which supply meets demand to the one in which it can’t. Indeed, this has already happened in many areas around the world, and will continue to happen in the future as the availability of arable land and fresh water decline [48]. Just because these regional crises have not yet spread to the developed world, let alone to become global food and/or water shortages, does not mean that such global crises are not already unfolding or that they can’t happen in the near future.

Tepid as it is by comparison to what lies just ahead, the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic has awakened many people to the unappreciated complexity, fragility, and outsized collateral consequences of today’s seemingly unstoppable globalized system. The explicit tension between the health of the economy and human health—weighing economic loss against mortality rates—is just one facet of a broader set of questions touched on here: what other values are being foolishly dismissed in deference to the self-imposed primacy of economic growth concerns? Ecosystems and planetary limits, equity and dignity, and a more viable future all succumb to a narrow monetary definition of economic growth at present. The disruption witnessed in the coronavirus pandemic provides a comparatively benign preview of the kinds of forced sacrifices that may be in store if humanity fails to alter course, and has permitted unintentional exploration of different modes of working and living. Among other things, the experience emphasized the importance of having plans and competent experts in place for effective mitigation—to the extent possible.

By analogy, early flying machines invariably crashed despite an exhilarating brief airborne interval—mainly because the contraptions were simply not built according to aerodynamic principles of sustainable flight. Likewise, the present economy is not built on principles for sustainable, steady-state operation. The ground is rushing up, despite the euphoric feeling of wind in our hair. A techno-optimist might suggest digging a hole ahead of the falling mass. Perhaps a more enduring remedy is a different machine.

Many academics recognize the problems associated with current economic and political structures. Some advocate for carbon taxes and similar economic instruments to incorporate “externalities” not currently captured in pricing structures. Some argue that renewable energy can replace fossil fuels globally and perhaps save the day [49], despite concerns about potentially lower net energy yields and the drastic changes in consumption patterns and behavior that would be necessary [13]. Some recognize that continued growth will put additional near-term pressure on the system, but anticipate payoff in the form of a “demographic transition” in developing countries that will ultimately stabilize global population, at a higher standard of living than today. It is completely understandable why this would be dearly held as a worthy goal. Why are billions of people intrinsically any less deserving than the lucky minority in wealthy countries? Shouldn’t everyone have their chance? Growth can solve all problems, the thinking goes. But is it possible? Is nature on board?

Humans collectively must ultimately face the uncomfortable question of whether Earth’s natural systems can support 8 billion or more people at a modern standard of living. Since the resource footprint of a U.S. citizen is at least four times that of the global average, the key question is whether the planet can support an increase in material throughput four times higher than present when the strain is apparent already. As noble as it may be to wish a modern living standard for an eventual ten billion or more people, it is likely that committing to such a course could result in more human suffering than would transpire under the adoption of more modest goals. The responsible path is to reduce global resource dependencies and abandon the imperative for growth starting now.

Human societies can and must recognize and acknowledge such limitations, as jarring as that may be. Modern monetary theory aside, responsible adults learn to live within their means; “A business [person] would not consider a firm to have…achieved viability if [they] saw that it was rapidly consuming its capital. How, then, could we overlook this vital fact when it comes to that very big firm, the economy of the Spaceship Earth?” [15] Earth has provided a resource inheritance of unimaginable value, which humans are exploiting as quickly as political and market systems will allow. That has been the easy part. The path forward must be more carefully considered. Continued fixation on growth threatens to drown out responsible action. Growth needs to be recognized as the beloved enemy: humankind can never hate it for all it has provided in the past, but neither can we afford to carry it into the future. Continuing to promote growth as a goal—even if for noble reasons of equity in the developing world—risks overshooting Earth’s steady-state means and making the world ultimately worse for all.

Issues as important as those raised in the 1972 Limits to Growth [1] deserve repeating and, buttressed by the record of the ensuing decades, are hardly outdated or discredited. The central message of that work was simply that humanity was on a path toward overshoot and collapse, and today it is clear that numerous natural systems on Earth are experiencing some form of collapse. It is simply too early to see any marked departures from the Limits to Growth model runs, which show dramatic upheavals around the middle of this century [50].

In sum, human society is using the wrong map for a successful future. It can no longer afford to emphasize growth under the assumption that the Earth’s ecosystems will tolerate any action that humans elect to take. On a frontier, one has little need for a map in deciding where to site a house or well or latrine. But operating in the developed world requires maps indicating zoning laws, utility services, and property boundaries. Likewise, human civilization can no longer “wing it” by developing arbitrary constructs without careful adherence to biophysical constraints.

7. Developing a PLAN for the Future

The goal of this Perspective is to get academics and others to step back from the familiar up-close view of their place and trajectory in the world to see a broader perspective on the challenges modern society faces going forward. The past success leading to this moment does not portend a similar future, due to the explosion of people and resource use that has been unleashed in a very short amount of time, and one does not have to look far to see seemingly intractable global-scale predicaments that interconnect and appear to be growing more severe. These are unprecedented, abnormal times, and sub-systemic, if not systemic breakdown can only be avoided if its prospect is taken seriously.

The authors acknowledge that confronting these challenges will require substantial departures from the workings of current institutions and cultural systems in order to forge a path compatible with planetary limits. Political and economic systems will need to address fundamental drivers for growth, productivity, and resource exploitation in modern society, incorporating more systematically the important roles of ecological services and of community. Entrenched institutions will resist big changes, and leaders of these institutions will argue that departures from the present trajectory threaten prosperity and happiness. The authors are at pains to assure readers that our greatest hope is for maximizing long term human wellbeing. The concern is, however, that holding on too long to the current path will translate to maximal suffering by overextending humanity’s claim on nature and plunging future generations into intractable decline or collapse, left with a depleted resource base. Ethical issues accumulate rapidly and lead to questions of meaning and existence that humans have long pondered, though now made critically important by the dilemmas outlined above. What ultimately matters? What can we, as academics, do? At stake is nothing less than the preservation of the sum of human academic accomplishment for posterity.

The current structure of academia, which arose in the nineteenth century from a reductionist approach to knowledge creation, is not well suited to fostering an integrative understanding of the challenges now facing humanity, much less to developing a framework for a future that is compatible with planetary limits. Divisions of academics into colleges and departments, and disciplines and subdisciplines, facilitate deep research in relatively narrow areas. Professional societies are generally organized around specific disciplines (or intersections between two disciplines), and are largely populated by scholars with similar training (e.g., PhDs in a given field). Rarely are societies or academic networks organized around a truly transdisciplinary theme, and welcoming of scholars from all traditional disciplines.

Here the authors announce the launch of the Planetary Limits Academic Network (PLAN). PLAN is designed as a community of scholars (both inside and outside the academy) who appreciate the complex nature of planetary limits and are open to collaboration on actionable research addressing the existential predicament our civilization faces. We seek to identify scholars who have already come to understand the interlocking issues outlined in this Perspective, and who wish to shepherd the critical intellectual transition from awareness to collaborative development of systems-level thought.

Considerable scholarly work will be needed to develop an integrative understanding of planetary limits, and to develop appropriate responses, which might include envisioning and laying the groundwork for realistic scenarios that lie between techno-utopian and apocalyptic. A key element of this network is to catalyze new collaborative efforts in this space, by making connections among scholars hailing from different disciplines who are interested in similarly broad intellectual questions.

|

Box 1

Preliminary set of foundational principles for the Planetary Limits Academic Network.

1. Humans are a part of nature, not apart from nature.

2. Non-renewable materials cannot be harvested indefinitely on a finite planet.

3. The ability of Earth’s ecosystems to assimilate pollution without consequences is finite.

4. Energy throughput is essential to all human activities, including the economy.

5. Technology is a tool for deploying, not creating energy.

6. Fossil fuel combustion is the primary cause of ongoing global climate change.

7. Exponential growth, whether of physical or economic form, must eventually cease.

8. Today’s choices can simultaneously create problems for and deprive resources from future generations.

9. Human behavior is consciously and unconsciously shaped by mental models of culture that, while mutable, impose barriers to change.

10. Apparent success for a few generations during a massive draw-down of finite resources says little about chances for long-term success.

|

As a framework for building this network, the authors propose a preliminary set of “foundational principles”—key assertions about the nature of the coupled human-natural system that we consider to be self-evident, even though many scholars may not be consciously aware of them. The tentative set of principles presented in Box 1 aims to capture the common understandings that will bring PLAN members together. The authors invite constructive criticisms of this set of principles, as the current construction is limited by the disciplinary perspectives of the five authors. But perhaps more importantly, interested colleagues from all disciplines are encouraged to join the PLANetwork to help advance this essential area of scholarship.

For those who wish to dive more deeply into the implications of these foundational principles, the authors have developed a preliminary set of working hypotheses (Appendix A): assertions that may not be self-evident, but which we consider to be almost certainly true, based on current evidence. Together with the foundational principles, these working hypotheses constitute the essence of our worldview. While we remain open to evidence that contradicts these working hypotheses, we believe that PLAN can make the biggest impact through a scholarly examination of the consequences of these hypotheses.

Many individual scholars already work on relevant pieces of this puzzle, notably ecological and biophysical economists and de-growth scholars, so the authors are not presuming some whole-cloth invention of new fields and new research. Instead, we hope to see a disparate set of scholars from fields that do not currently have significant engagement with these topics unite under a common umbrella sharing similar over-arching concerns and approach, while also attracting professional migration into this existentially important space. The scale of this problem is massive, touching on all corners of humanity. Thus a credible effort needs historians, anthropologists, scientists, engineers, psychologists, economists, experts in business, trade, and communications, artists, theologians, and every other academic field to harness the knowledge and wisdom of all humanity.

Our hope is that we might spark debate and deep thinking about how human civilization might thrive for millennia to come, rather than simply survive the bottlenecks of the next few decades. Any scholar finding resonance in this message might ask what role their current research plays in addressing these issues. Ultimately, what is important? What elements of your work can contribute to a better future? The authors encourage bold migration into this intellectual space in order to achieve critical mass in understanding how human activity might fit within planetary limits, and welcome all interested scholars to join the Planetary Limits Academic Network (planetarylimits.net).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank several colleagues who read earlier drafts of this paper, including Gary Fugle, Ed Vine, and Kim Griest. The authors are also grateful to two anonymous reviewers, whose helpful feedback considerably improved our Perspective.

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Download Supplementary data 1.

References

[1] D.H. Meadows, D.L. Meadows, J. Randers, W.W. Behrens III, Limits to Growth, Signet, 1972, https://doi.org/10.1349/ddlp.1.

[2] B.K. Sovacool, S.E. Ryan, P.C. Stern, K. Janda, G. Rochlin, D. Spreng, M.J. Pasqualetti, H. Wilhite, L. Lutzenhiser,

Integrating social science in energy research,

Energy Research & Social Science, 6 (2015), pp. 95-99, 10.1016/j.erss.2014.12.005

[3] R.W. Scholz, G. Steiner

The real type and ideal type of transdisciplinary processes: part I—theoretical foundations

Sustainability Science, 10 (4) (2015), pp. 527-544, 10.1007/s11625-015-0326-4

[4] W. Steffen, K. Richardson, J. Rockstrom, S.E. Cornell, I. Fetzer, E.M. Bennett, R. Biggs, S.R. Carpenter, W. de Vries, C.A. de Wit, C. Folke, D. Gerten, J. Heinke, G.M. Mace, L.M. Persson, V. Ramanathan, B. Reyers, S. Sörlin,

Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet,

Science, 347 (2015), p. 1259855, 10.1126/science.1259855

[5] A. Abbott,

Chaos of Disciplines, The University of Chicago (2001)

[6] W. Catton,

Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change,

University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois (1980)

[7] S.H. Mohr, J. Wang, G. Ellem, J. Ward, D. Giurco,

Projection of world fossil fuels by country,

Fuel, 141 (2015), pp. 120-135, 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.10.030

[8] B.K. Sovacool,

How long will it take?,

Conceptualizing the temporal dynamics of energy transitions, Energy Research & Social Science, 13 (2016), pp. 202-215, 10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.020

[9] B.K. Sovacool, F.W. Geels,

Further reflections on the temporality of energy transitions: A response to critics,

Energy Research and Social Science, 22 (2016), pp. 232-237, 10.1016/j.erss.2016.08.013

[10] V. Smil,

Examining energy transitions: A dozen insights based on performance,

Energy Research and Social Science, 22 (2016), pp. 194-197, 10.1016/j.erss.2016.08.017

[11] W. Rees

The fractal biology of plague and the future of civilization,

The Journal of Population and Sustainability, 5 (2020), pp. 15-30, 10.3197/jps.2020.5.1.15

[12] C.A.S. Hall, J.G. Lambert, S.B. Balogh,

EROI of different fuels and the implications for society,

Energy Policy, 64 (2014), pp. 141-152, 10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.049

[13] R. Heinberg, D. Fridley,

Our Renewable Energy Future: Laying the Path for One Hundred Percent Clean Energy,

Island Press, Washington, D.C. (2016),

https://ourrenewablefuture.org/

[14] E.F. Schumacher,

Small is Beautiful,

Harper Perennial (1973)

[15] K.E. Boulding,

The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth,

H. Jarrett (Ed.), Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (1966)

[16] S.H.M. Butchart, M. Walpole, B. Collen, A. van Strien, J.P.W. Scharlemann, R.E.A. Almond, J.E.M. Baillie, B. Bomhard, C. Brown, J. Bruno, K.E. Carpenter, G.M. Carr, J. Chanson, A.M. Chenery, J. Csirke, N.C. Davidson, F. Dentener, M. Foster, A. Galli, J.N. Galloway, P. Genovesi, R.D. Gregory, M. Hockings, V. Kapos, J.-F. Lamarque, F. Leverington, J. Loh, M.A. McGeoch, L. McRae, A. Minasyan, M.H. Morcillo, T.E.E. Oldfield, D. Pauly, S. Quader, C. Revenga, J.R. Sauer, B. Skolnik, D. Spear, D. Stanwell-Smith, S.N. Stuart, A. Symes, M. Tierney, T.D. Tyrrell, J.-C. Vie, R. Watson,

Global Biodiversity: Indicators of Recent Declines,

Science, 328 (5982) (2010), pp. 1164-1168, 10.1126/science.1187512

[17] C. Costello, S.D. Gaines, J. Lynham,

Can Catch Shares Prevent Fisheries Collapse?,

Science, 321 (5896) (2008), pp. 1678-1681, 10.1126/science.1159478

[18]

T. Gleeson, Y. Wada, M.F.P. Bierkens, L.P.H. van Beek,

Water balance of global aquifers revealed by groundwater footprint,

Nature, 488 (7410) (2012), pp. 197-200, 10.1038/nature11295

[19]

L.F. Konikow, E. Kendy,

Groundwater depletion: A global problem,

Hydrogeology Journal, 13 (1) (2005), pp. 317-320, 10.1007/s10040-004-0411-8

[20]

Y. Wada, L.P.H. van Beek, C.M. van Kempen, J.W.T.M. Reckman, S. Vasak, M.F.P. Bierkens,

Global depletion of groundwater resources,

Geophysical Research Letters, 37 (2010), p. L20402, 10.1029/2010GL044571

[21]

IPCC, Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2014.

[22]

N.J. Hagens,

Economics for the future – Beyond the superorganism,

Ecological Economics, 169 (2020), p. 106520, 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106520

[23] S.E. Thompson, J.L. Coughlin, K. Hoffman, F. Mullally, J.L. Christiansen, C.J. Burke, S. Bryson, N. Batalha, M.R. Haas, J. Catanzarite, J.F. Rowe, G. Barentsen, D.A. Caldwell, B.D. Clarke, J.M. Jenkins, J. Li, D.W. Latham, J.J. Lissauer, S. Mathur, R.L. Morris, S.E. Seader, J.C. Smith, T.C. Klaus, J.D. Twicken, J.E. Van Cleve, B. Wohler, R. Akeson, D.R. Ciardi, W.D. Cochran, C.E. Henze, S.B. Howell, D. Huber, A. Prša, S.V. Ramírez, T.D. Morton, T. Barclay, J.R. Campbell, W.J. Chaplin, D. Charbonneau, J. Christensen-Dalsgaard, J.L. Dotson, L. Doyle, E.W. Dunham, A.K. Dupree, E.B. Ford, J.C. Geary, F.R. Girouard, H. Isaacson, H. Kjeldsen, E.V. Quintana, D. Ragozzine, M. Shabram, A. Shporer, V.S. Aguirre, J.H. Steffen, M. Still, P. Tenenbaum, W.F. Welsh, A. Wolfgang, K.A. Zamudio, D.G. Koch, W.J. Borucki,

Planetary Candidates Observed by Kepler. VIII. A Fully Automated Catalog with Measured Completeness and Reliability Based on Data Release 25,

The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 235 (2018), p. 38, 10.3847/1538-4365/aab4f9

[24] IPAC, IPAC Exoplanet Archive, (2020). https://exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu.

[25] J. Solé, R. Samsó, E. García-Ladona, A. García-Olivares, J. Ballabrera-Poy, T. Madurell, A. Turiel, O. Osychenko, D. Álvarez, U. Bardi, M. Baumann, K. Buchmann, Í. Capellán-Pérez, M. Cerný, Ó. Carpintero, I. De Blas, C. De Castro, J.-D. De Lathouwer, C. Duce, L. Eggler, J.M. Enríquez, S. Falsini, K. Feng, N. Ferreras, F. Frechoso, K. Hubacek, A. Jones, R. Kaclíková, C. Kerschner, C. Kimmich, L.F. Lobejón, P.L. Lomas, G. Martelloni, M. Mediavilla, L.J. Miguel, D. Natalini, J. Nieto, A. Nikolaev, G. Parrado, S. Papagianni, I. Perissi, C. Ploiner, L. Radulov, P. Rodrigo, L. Sun, M. Theofilidi,

Modelling the renewable transition: Scenarios and pathways for a decarbonized future using pymedeas, a new open-source energy systems model,

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 132 (2020), p. 110105, 10.1016/j.rser.2020.110105

[26] G.M. Turner, B. Elliston, M. Diesendorf,

Impacts on the biophysical economy and environment of a transition to 100% renewable electricity in Australia,

Energy Policy, 54 (2013), pp. 288-299, 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.11.038

[27] C. Hall, J. Day,

Revisiting the Limits to Growth After Peak Oil,

American Scientist, 97 (3) (2009), p. 230, 10.1511/2009.78.230

[28] J.W. Day, C.F. D’Elia, A.R.H. Wiegman, J.S. Rutherford, C.A.S. Hall, R.R. Lane, D.E. Dismukes,

The energy pillars of society: perverse interactions of human resource use, the economy, and environmental degradation,

BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality, 3 (2018), p. 2, 10.1007/s41247-018-0035-6

[29] UN, Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 2015.

[30] J. Hickel,

The contradiction of the sustainable development goals: Growth versus ecology on a finite planet,

Sustainable Development, 27 (2019), pp. 873-884, 10.1002/sd.1947

[31] J. Polimeni, K. Mayumi, B. Alcott, M. Giampietro,

The Jevons Paradox and the Myth of Resource Efficiency Improvements,

Routledge (2007)

[32] A.J. Jarvis, D.T. Leedal, C.N. Hewitt,

Climate-society feedbacks and the avoidance of dangerous climate change,

Nature Climate Change, 2 (9) (2012), pp. 668-671, 10.1038/nclimate1586

[33] T. Murphy, Energy and Human Ambitions on a Finite Planet, Chapter 2, eScholarship, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.21221/S2978-0-578-86717-5.

[34] M. Sarrica, S. Brondi, P. Cottone, B.M. Mazzara,

One, no one, one hundred thousand energy transitions in Europe: The quest for a cultural approach,

Energy Research & Social Science, 13 (2016), pp. 1-14, 10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.019

[35] C. Glacken,

Traces on the Rhodian Shore, University of California Press (1967)

[36] T. Love, C. Isenhour,

Energy and Economy: Recognizing high energy modernity as an historical period,

Energy and Economy, 3 (2016), pp. 6-16, 10.1002/sea2.12040

[37] J.S. Mill,

Principles of Political Economy,

John W. Parker, London (1848)

[38] A. Smith, The Wealth of Nations, W. Strahan and T. Cadell, London, 1776.

[39] T. Malthus

On the Principle of Population, J. Johnson, London (1798)

[40] L. Walras, The Elements of Pure Economics, Lausanne, 1874.

[41] B. Czech,

Supply Shock: Economic Growth at the Crossroads and the Steady State,

New Society Publishers (2013)

[42] S. Bichler, J. Nitzan,

Capital accumulation: fiction and reality,

Real-World Economics Reviews, 72 (2015), p. 47,

http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue72/BichlerNitzan72.pdf

[43] H. Barnett, C. Morse,

Scarcity and Growth: The Economics of Natural Resource Availability,

Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (1963)

[44] R.M. Solow,

The Economics of Resources or the Resources of Economics,

The American Economic Review, 64 (1974), pp. 1-14,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1816009

[45] C. Cleveland, Natural Resource Scarcity and Economic Growth Revisited: Economic and Biophysical Perspectives, in: Ecological Economics: The Science and Management of Sustainability, Columbia University Press, 1991.

[46] G. D’Alisa, F. Demaria, G. Kallis,

DEGROWTH: A Vocabulary for a New Era,

Routledge, New York (2015)

[47] H.E. Daly, J. Farley,

Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications,

Island Press (2003)

[48] N.M. Ahmed,

Failing States, Collpasing Systems: Biophysical Triggers of Political Violence, Springer (2017)

[49] E. Larson, C. Greig, J. Jenkins, E. Mayfield, A. Pascale, C. Zhang, J. Drossman, R. Williams, S. Pacala, R. Socolow, E.J. Baik, R. Birdsey, R. Duke, R. Jones, B. Haley, E. Leslie, K. Paustian, A. Swan,

Net Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts,

Princeton University, Princeton, NJ (2020)

[50] D. Meadows, J. Randers, D. Meadows,

The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update,

Earthscan, New York (2004)

|

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

T.W. Murphy Jr., Professor of Physics, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

D.J. Murphy, Associate Professor of Environmental Studies, St. Lawrence University, Canton, NY, USA.

T.F. Love, Emeritus Professor of Anthropology, Linfield University, McMinnville, OR, USA.

M.L.A. LeHew, Professor of Interior Design & Fashion Studies, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA.

B.J. McCalle, Professor of Sustainability and Executive Director, Hanley Sustainability Institute, University of Dayton, Dayton, OH, USA.

|