An odd paradox emerges when we consider our economic objectives, and question the priority routinely accorded to “growth”.

If we continue our obsession with growth, we will accelerate the deterioration of the energy-driven economy, worsen our environmental predicament and squander the resources which might otherwise have formed the basis of a sustainable economy. If, further, we continue to see the financial system as an adjunct of our pursuit of “growth”, we invite systemic collapse.

The irony here, of course, is that the pursuit of growth is, in any case, the pursuit of a chimera.

Conversely, if we aim for stability, and redesign our failing financial system accordingly, we might yet succeed in combining prosperity with sustainability.

Context – failure on two fronts

If – just for a moment – we ignore financial issues, and concentrate wholly on material metrics such as resources, the environment, population numbers, food supply and the physical output of goods and services, it soon becomes clear that we are either at, or very near, the end of “growth”, unless indeed we have already passed the point of down-turn. Essentially, the modern industrial economy is the product of the use of abundant, low-cost energy from fossil fuels. These fuels are ceasing to be cheap at the same time that their use is colliding with the limits of environmental tolerance.

Conversely, if we focus entirely on the financial, it becomes equally clear that a system reliant on QE and other forms of monetary gimmickry is at existential risk. We can trace the origins of this process back to the 1990s, and the recognition (though not the explanation) of “secular stagnation”. The authorities’ chosen ‘fix’ for this perceived problem was to use debt to stimulate demand, on the assumption that cheap and abundant credit would prove to be a magic elixir for the restoration of growth to the economy. From there, it was a dangerously easy step from credit expansion to the back-stopping of debt (and asset markets) with monetization.

What we have, then, is (a) a material, physical or real economy that has reached or passed peak output, and (b) a counterpart financial economy which, barring a drastic change of direction, is heading towards collapse.

We’re not yet at the point where there are “no fixes” for these issues, but the odds seem stacked against the determined and effective efforts that would be required to achieve sustainability in the aftermath of growth. Might we yet be forced, kicking and screaming, into wiser decisions?

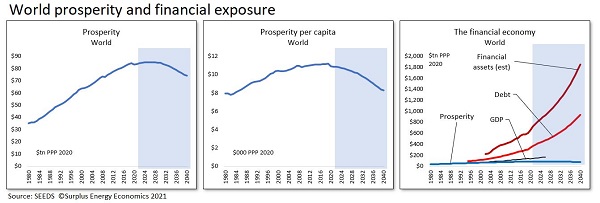

These situations are set out in Figure 1, using data sourced from the SEEDS economic model. Aggregate prosperity has continued to increase (but is nearing the point of down-turn), whilst prior growth in prosperity per capita has already gone into reverse. Both debt and the broader and much bigger category of financial assets (in effect, the liabilities of the household, corporate and government sectors) have soared, and seem destined to carry on doing so, unless and until the financial system implodes.

Figure 1 ~ Click image to enlarge

Two excellent, must-read recent papers have reached stark conclusions about the ‘real’ and the ‘financial’ economies. Gaya Herrington, in a report which concentrates on physical, non-financial metrics such as population numbers, natural resources and the environment, concludes that, under any BAU (“business as usual”) scenario, we face “a collapse pattern” which can only be softened (into “moderate decline”) by advances in technology far beyond historic rates of innovation and adoption.

In Quantitative easing: how the world got hooked on magicked-up money, published by Prospect, Ann Pettifor says that “[g]oing cold turkey would finish off a dysfunctional global financial system that’s now hopelessly addicted to emergency infusions”.

Neither paper gives us no hope at all, but both point to the need for radical change. On the financial situation, Ms Pettifor concludes that “[t]he only solution is surgery on the system itself”. Ms Herrington sets out an alternative SW (“sustainable world”) scenario which, whilst it cannot restore growth, does at least offer stability. Unfortunately, SW does not correlate well with what’s actually happening.

We can put these ‘potential positives’ into a single conclusion. The best, indeed the only way to achieve economic sustainability is to abandon all aspects of BAU that are geared towards the attainment of growth, and to shift our objectives from growth to resilience. The financial system, likewise, needs to transition way from an obsession with expansion, and aim instead for functional effectiveness in a non- or post-growth World.

In short, the precondition both for economic and for financial stability is that we ditch our obsession with “growth”. The same, of course, applies to our environmental best interests. The biggest single threat to environmental sustainability is our worship of “growth”.

Difficult, straightforward, paradoxical

Simply stated, the required transition is from a state of mind which obsesses over growth to a state of mind which prioritizes stability.

Attaining this transition is at once difficult, straightforward and paradoxical.

It’s difficult, because the desirability of “growth” is deeply entrenched both in institutions and in the collective mind-set. Political leaders routinely promise growth, businesses strive to achieve it, and the financial system is entirely predicated on it. Advocates of voluntary “de-growth” have never managed to make meaningful inroads into this obsession with “growth”.

It’s straightforward, in the sense that growth is already over. The continued pursuit of growth is the pursuit of the unattainable. As the ECoEs (the Energy Costs of Energy) of coal, oil and gas have risen, the economic value that we derive from the use of fossil fuels has started to diminish. Assertions that we can replace all of this value using renewable sources of energy (REs) are based on little more than wishful thinking and mistaken extrapolation. Apart from anything else, RE expansion requires inputs which, at least for the present, can only be provided by the use of energy from fossil fuels.

To be clear about this, we must make every effort to develop renewable energy supply, but we shouldn’t delude ourselves into the belief that REs can replicate the economic characteristics of fossil fuels. Well-managed, a transition to REs can contribute to stability. What REs cannot do is deliver a return to growth.

As well as being both difficult and straightforward, the required transition is paradoxical, because the pursuit of growth is the best way to ensure economic decline. If sustainability is set as the primary objective, this aim might be achievable. But the biggest obstacle to the attainment of sustainability is our obsession with growth.

Measuring our predicament

The purpose of the SEEDS economic model is to provide holistic interpretation by putting together the ‘real’ and the ‘financial’ economies. SEEDS does this by calibrating prosperity from energy principles, and delivering results in a monetary format which enables us to benchmark the financial system.

SEEDS demonstrates a clear linkage between ECoEs and prosperity. For much of the industrial age, ECoEs trended downwards. This meant that, for so long as aggregate energy supply at least kept up with increases in population numbers, the material prosperity of the average person improved.

The fundamental change occurred when ECoEs stopped declining, and started to rise. At first, this happened only gradually. However, the upwards trend in the ECoEs of fossil fuels is an exponential one.

During the 1980s, a rise in trend all-sources ECoEs of 0.8% – from 1.8% in 1980 to 2.6% in 1990 – didn’t matter all that much, and was, in any case, well within margins of error that are accepted in economic calibration. In short, this early rise in ECoEs wasn’t large enough to force itself upon our attention.

What happened during and after the 1990s, however, was far more serious. In the 1990s, ECoEs rose by 1.5%, from 2.6% in 1990 to 4.1% in 2000. Trend ECoEs then increased by 2.2% between 2000 and 2010, and by a further 2.6% between 2010 and 2020. This put ECoEs at 8.9% last year, compared with 1.8% back in 1980.

Since an ECoE of 8.9% still leaves surplus (ex-ECoE) energy at more than 90% of total energy supply, it might at first sight seem surprising that prior growth in per capita prosperity should already have gone into reverse.

The explanation for this sensitivity lies in the complexity, and the correspondingly high maintenance demands, of the modern economy. The vast bulk of the economic value derived from energy is required for the upkeep and renewal of systems. Even under the best of circumstances, the scope for growth is constrained by the ‘burden of maintenance’.

SEEDS analysis reveals two very strong correlations here. One of these is between ECoE and prosperity, and the other connects complexity with ECoE-sensitivity. In the advanced economies of the West, prior growth in prosperity goes into reverse at ECoEs between 3.5% and 5.0%. Less complex EM economies can carry on increasing their prosperity until ECoEs are between 8% and 10%.

The latter connection helps explain the apparent divergence between the advanced and the emerging economies over the past twenty years. As of 2000, global trend ECoE was, at 4.1%, well within the threshold at which Western prosperity starts to contract. At that level of ECoE, however, EM countries remained capable of growth. This is why, whilst people in countries like America and Britain have been getting poorer since the early 2000s – and using financial gimmickry to delude themselves to the contrary – Chinese, Indian and other EM citizens have continued to get better off.

A failure to recognize the differing effects of ECoEs on differing economies has led to a great deal of mistaken interpretation of the divergence between growth in countries like China and “stagnation” (in reality, de-growth) in the West. Westerners haven’t become uniformly lazy or complacent over the past two or three decades, any more than EM citizens have been uniformly more industrious and productive.

Rather, the greater complexity of the Western economies has resulted in their earlier exposure to the consequences of rising ECoEs. With ECoEs set to exceed 9% this year, we are well into the ‘zone of inflection’ in which EM prosperity, too, starts to decline.

An accommodation with de-growth?

In this sense, then, growth is over, and “de-growth” has begun. But there’s a world of difference between an economy getting gradually poorer and an economy careering towards a cliff-edge. If we continue our frantic pursuit of growth, the likelihood is that our options will diminish, as resources are exhausted, population numbers continue to increase, environmental and ecological deterioration accelerates and a rickety, Heath Robinson financial system reaches the point of self-destruction.

Of course, nobody would expect political leaders to stop promising growth, or businesses to stop pursuing it. No president or prime minister is likely to proclaim, like the fictional Duke of Omnium, that the country is fine how it is, and the job of government is to keep it that way. No business leader is likely to tell shareholders that corporate strategy is to turn away from expansion, and instead to maintain the company as a reliable generator of value for its owners.

But to concentrate on stated intentions is to overlook mechanisms. If the Holy Grail of “transition to renewables” fails to replace the energy value hitherto derived from fossil fuels, then it will be futile to carry on denying the reality of de-growth.

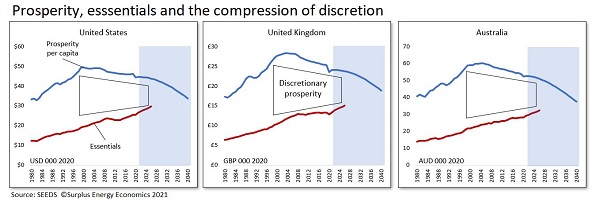

As we’ve seen in previous discussions, prosperity is declining, whilst the real cost of estimated essentials is rising. As you can see in Figure 2, it’s clear that discretionary prosperity is being compressed, and that continued increases in discretionary consumption have been made possible only by continued credit expansion.

Three processes – prosperity deterioration, the rising cost of essentials and the approach of credit exhaustion – are likely to force businesses into the adoption of policies consistent with the Surplus Energy Economics taxonomy of de-growth.

Some companies, for instance, will work out that switching from a ‘high-volume, low-margin’ to a ‘high-margin, low-volume’ model can support revenues and earnings as the discretionary prosperity of the median consumer declines. Producing less, whilst charging more for it, is one way of maintaining profitability whilst also driving down emissions of CO2.

A de-growing economy is also a de-complexifying one, and this trend is likely to encourage, or indeed to compel, businesses to simplify both their product offerings and their production processes, at the same time tightening their supply lines in pursuit of resilience. Of course, the continuing contraction of discretionary prosperity may shrink or eliminate some sectors, whilst others will be de-layered by customer pursuit of simplification.

Governments, too, will not be immune from these processes. As bridging the ‘discretionary prosperity gap’ by taking on yet more debt ceases to be feasible, the public is likely to become increasingly discontented about the increasing slice of their resources being taken by essentials, be these household necessities or the services provided by government. We should anticipate demands for intervention, particularly over the rising cost of energy.

In other words, businesses and governments might not disavow the pursuit of “growth” – it would be remarkable if they did – but trends are likely to push them in this same direction. If we’re looking for some encouragement, scant though it is, we might note that governments, in promising to “build back better”, have not promised to “build back bigger”.

Figure 2 ~ Click image to enlarge