Despoiling the Desert

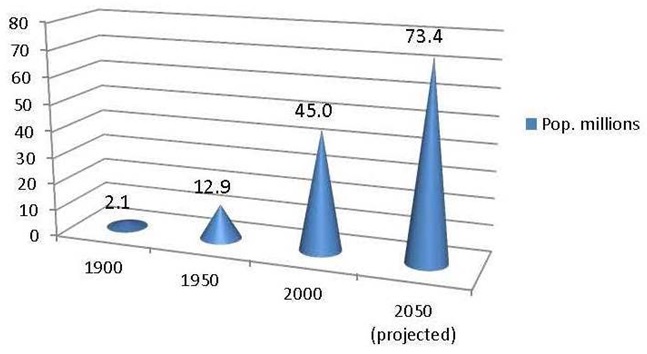

Over the past century, no region of the United States can match the vertiginous population growth of the American Southwest. In 1900, the combined populations of California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico totaled just 2 million. A century later, in 2000, this modest number had skyrocketed to 45 million. By 2050, the official demographic agencies of these states project a combined population of 73 million (Figure 1).

All at a time when the region’s freshwater sources are dwindling and its hot, dry climate getting even more unbearable due to anthropogenic climate change.

Figure 1. Combined Population of Five Southwestern States, 1900 to 2050 (millions)

Note: Includes California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and New Mexico

Graph provided by the author ~ Click image to enlarge

Such additional growth in an already overpopulated, overtaxed, and cluttered landscape is certainly not desirable, however much a post-industrial economy hooked on growth may depend on it. And while continued growth is certainly feasible – for a while – the more serious issue is whether continued growth or even current human numbers are sustainable.

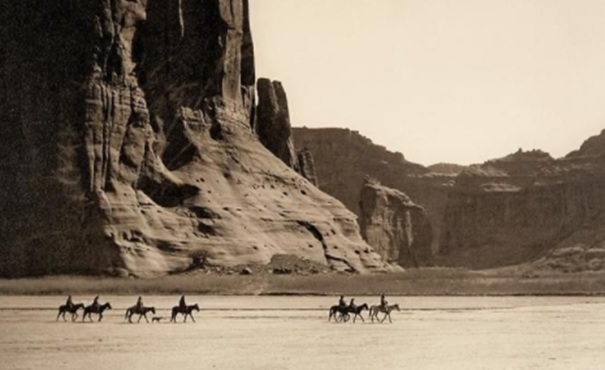

Until a few hundred years ago, the arid Southwest was thinly populated by scattered indigenous peoples such as the Chumash, Navajo, Apache, Ute, Pueblo, Hopi, and Zuni, among many other Amerindian tribes, longtime residents of a stark but hauntingly beautiful landscape (Figure 2). From the 1500s on, they were joined by Hispanic settlers, mostly clustered at missions, farms, and ranches along the California coast and in the fertile Rio Grande Valley bisecting New Mexico.

Figure 2. Navajo riders on horseback in Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, 1904.

Photographed by Edward Curtis ~ Click image to enlarge

Over the centuries, these diverse peoples and the societies they built had adapted to the punishing heat and the harsh desert conditions, learning to use and conserve scarce water resources to support their agriculture, which in turn, supported their relatively low numbers.

In the 20th century, all this changed forever. The advent of air conditioning and humongous water projects in the Colorado River Basin spurred migration and settlement on a vast scale by mostly mid-western and northeastern Euro-Americans. These newcomers were lured to the “Sunbelt” by the promise of jobs in the booming defense sector or acting careers in Hollywood. They came for Nevada’s gaming and girls or for Arizona’s dry air, and everyone was enchanted by Southern California’s intoxicating Mediterranean climate and legendary beaches.

Don Henley and Glenn Frey of The Eagles wrote evocatively about this magical, magnetic quality in the lyrics to “The Last Resort,” the final song on The Eagles’ iconic 1976 album Hotel California. It’s a brooding song about how we humans (inevitably?) destroy the places we love:

She heard about a place people were smiling

They spoke about the red man's ways

How they loved the land

They came from everywhere to the great divide

Seeking a place to stand or a place to hide

Down in the crowded bars, out for a good time

Can't wait to tell you all what it's like up there

They called it paradise, I don't know why

Somebody laid the mountains low while the town got high

Then the chilly winds blew down across the desert

Through the canyons of the coast to the Malibu

Where the pretty people play, hungry for power

To light their neon way and give them things to do

Some rich men came and raped the land, nobody caught 'em

Put up a bunch of ugly boxes

And Jesus, people bought 'em

They called it paradise, the place to be

They watched the hazy sun sinking in the sea

Henley told Rolling Stone magazine in 1978:

“The gist of the song was that when we find something good, we destroy it by our presence – by the very fact that man is the only animal on earth that is capable of destroying his environment….We have mortgaged our future for gain and greed."

The 1982 experimental, cult film Koyaanisqatsi by Santa Fe-based independent filmmaker Godfrey Reggio told a similar story, one of collision between modern technology and lifestyles and the enchanted landscapes and folkways they replace. “Koyaanisqatsi” is a Hopi word meaning “life out of balance.”

Reining in the River

Two massive arch-gravity concrete dams built on the tumbling and churning Colorado River in the heart of 20th century symbolized “progress” as conceived of at that time. They impounded the river for man’s use and abuse, both taming and harnessing these mighty waters, which over the eons (7 million years) had eroded and transported countless cubic miles of sedimentary rock strata while carving and sculpting that Wonder of the World known as the Grand Canyon.

The massive Hoover Dam, downstream of the Grand Canyon, was dedicated by FDR in 1936 during the depths of the Great Depression. It impounded Lake Mead, the largest reservoir by volume (when full) in the entire United States. Hoover was built by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and thousands of workers, more than 100 of whom sacrificed their lives in erecting this monumental mammoth. The dam and reservoir provide hydroelectricity, flood control, water storage, regulation, and recreation. Lake Mead furnishes essential water to an estimated 25 million customers, including tribes, farms, and major Southwestern cities such as Los Angeles, San Diego, Phoenix, and Las Vegas.

Upstream on the Colorado, above the Grand Canyon, the Bureau of Reclamation also built the Glen Canyon Dam, finished in 1966. It impounds Lake Powell, named for the Grand Canyon’s 19th century explorer John Wesley Powell. Glen Canyon (Figure 3) was a remote, inaccessible, and spectacular canyon known to few people, which meant that it had few defenders who fought against its desecration. Lake Powell has become a major destination for boaters, but has long been criticized as very wasteful of water due to excessive seepage and evaporation.

Of course, all that air conditioning and all those cars on all those clogged freeways in California and Arizona require energy, often provided by fossil fuels whose combustion contributes to the implacable increase of CO2 in the atmosphere and associated global warming. And all that water needed to irrigate crops and lawns, cook food, manufacture chips, and flush toilets has literally drained the Colorado River dry. It typically no longer reaches its mouth at the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California) in Mexico.

And now, the environmental (water and climate) chickens are coming home to roost.

Figure 3. One of many breathtaking side-canyons on Glen Canyon,

submerged when Lake Powell was impounded by the Glen Canyon Dam

on the Colorado River ~ Click image to enlarge

Converging Crises

In June 2021, authorities announced that Lake Mead’s water level had dropped to the lowest it has been in 84 years, since 1937, when the reservoir was first filling up. The lake’s volume is now at a mere 36% of its capacity when full, its water level having plummeted 143 feet since 2000, revealing a “bathtub ring” (Figure 4). This signified a grim milestone in the recent history of the Colorado River, whose flow has diminished by an estimated 20% over the past century.

As a result, next year, the Arizona’s tribes and farmers are facing cutbacks in water deliveries approaching half a million acre-feet, about 20% of the state’s allowance under the Colorado River Compact. Cuts for cities could soon follow if Lake Mead continues to shrink.

On the one hand, water experts are sounding the alarm. “It should represent an earthquake in people's sense of urgency, on all fronts,” Felicia Marcus, a visiting fellow at Stanford University’s Water in the West program, told the Arizona Republic. “We need to accelerate everything we can to use less water,” she added.

This includes a variety of measures, such as investments in wastewater recycling, capturing stormwater, remediating contaminated groundwater, promoting water-saving irrigation technologies, and offering homeowners cash rebates to replace their grass lawns with drought-tolerant landscaping (xeriscaping).

Figure 4. Lake Mead’s “bathtub ring” is clearly visible

LoggaWiggler from Pixabay ~ Click image to enlarge

On the other hand, growthmania still reigns supreme in a region that has exploded like the mushroom clouds that once blighted blue skies over the Nevada desert during the atmospheric nuclear testing era. The Southwest has seen explosive growth for the better part of a century and its construction sector, among others, depends on endless growth. In much of the Southwest, growth is almost a religion. The establishment – including both political parties – all but worships at the altar of growth. “In Growth We Trust” has supplanted “In God We Trust.”

The Hill reported in June 2021 that Nevada’s congressional delegation is promoting legislation to sell off 42,000 acres of public lands to boost new development in Las Vegas. The Southern Nevada Economic Development and Conservation Act hopes to lure over 820,000 new residents to Southern Nevada over next 40 years. Observes The Hill: “That means there will be hundreds of thousands of new consumers of the Colorado River in a fast-warming region in the nation’s driest state.”

Gary Wockner of the NGO Save the Colorado writes that:

“…although the system is collapsing, nearly 20 NEW DAMS are being planned up and down the Colorado River system. In Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming, water managers are hell-bent to fuel the collapse, diverting more water out of the river system faster than ever. It's a race to the bottom of every existing reservoir, literally an insane response to the drought and climate chaos.”

What is the “climate chaos” to which Wockner refers? Precisely this: the federal government’s Fourth National Climate Assessment indicates that for the rest of this century and beyond, the Southwest will heat up, Rocky Mountains snowpacks will shrivel, and stream flows will turn to trickles. The Assessment states unambiguously:

“Increases in temperature would also contribute to aridification (a potentially permanent change to a drier environment) in much of the Southwest, through increased evapotranspiration, lower soil moisture, reduced snow cover….These changes would tend to increase the duration and severity of droughts and generate an overall drier regional climate.”

California’s ongoing drought, which has already caused gigantic, devastating wildfires in the last several years, has gotten so bad that farmers are now pulling out almond trees, as “the famed farming valleys of California are being swept into what feels like permanent dryness,” reports Bloomberg.

Kissing Paradise Good-bye?

The converging crises of water, climate, and energy are forcing serious reconsideration of “pie in the sky” schemes that were once beyond the pale. One of these is eliminating Lake Powell, long the bane of environmentalists because it commits the sacrilege of submerging the once-sublime Glen Canyon, converting it from cathedral to gargantuan water storage facility. Environmentalist legend David Brower said that not opposing this project more vigorously was the greatest regret of his storied career. The more radical environmentalists have long fantasized about blowing up the Glen Canyon Dam which impounds Lake Powell. A “lite” version of this dark fantasy leaves the dam intact, but drains Lake Powell.

Draining Lake Powell, says the Glen Canyon Institute, is no longer just “tilting at windmills.” It is an idea whose time may have come: letting the water now stored in Powell (i.e., Glen Canyon) flow into and replenish shrunken Lake Mead downstream would result in less water overall lost to seepage. According to an Institute-commissioned, peer-reviewed study, this step would yield an annual savings of 300,000 acre-feet – equal to Nevada’s annual Colorado River water allocation.

Though draining Lake Powell would be a big step forward onto a more “sustainable” path, it is not a panacea that would permanently solve the river’s woes. The water savings it might yield would be guzzled up in just a few years, given the Southwest’s relentless growth and the insatiable thirst for ever more water this engenders.

Perpetual growth itself – deemed absolutely essential to our wellbeing by modern economists and politicians of all stripes – is causing the ecosystem to collapse. Christopher Clugston describes the paradox like this, “what we do to enable our existence simultaneously undermines our existence.” Or to paraphrase the late physicist Albert Bartlett, perpetual growth in a finite region or planet is an oxymoron – an impossibility theorem.

Like bacteria in a petri dish, are we doomed to grow until growth’s pressures trigger collapse? Those song lyrics by The Eagles quoted above seemed to think so, emphasizing in the last lines of “The Last Resort” the apparent difficulty of fallen mortals in acknowledging and accepting limits:

Who will provide the grand design, what is yours and what is mine?

Cause there is no more new frontier, we have got to make it here

We satisfy our endless needs and justify our bloody deeds

In the name of destiny and in the name of God.

And you can see them there on Sunday morning

Stand up and sing about what it's like up there

They called it paradise, I don't know why

You call some place paradise, kiss it goodbye...

Unless Southwesterners, and humanity writ large, can recognize that even “paradise” has limits, and we somehow learn to live within those limits, we will indeed kiss paradise goodbye. Not just the majestic and magical paradise of the Southwest, but our functioning ecosphere as well. This paradise is not just the only certain abode of life in a vast and inscrutable universe, but our species’ cradle, nursery, and home.