This article appeared first at The Overpopulation Project on May 3, 2021

Increasing economic inequality and accelerating ecological decline are the two great political challenges facing nations today. In recent decades, many complicated efforts to address these problems have been proposed or tried, but the problems have continued to worsen. Perhaps it is time to address them more directly.

I came of age politically forty years ago, eligible to vote for the first time in the United States in 1980. That was the election that put Ronald Reagan in the White House and, along with contemporary results in Germany, Great Britain and elsewhere ushered in a long period of neo-liberal economic policy in the developed world. The kind of “command and control” regulations that had begun to clean up the air and waterways in the developed world were out, “market-based” environmental solutions were in. High taxes on the wealthy were out, but that was OK: increased wealth among the wealthy would trickle down to poor people, making us all better off.

As these efforts proved themselves failures, conservative governments around the world simply redoubled efforts along the same lines: deeper tax cuts, more regulatory “relief” and voluntary environmental programs for corporations, more market discipline for the “unproductive” poor. When liberals took their turns in office, they offered slightly different versions on the same themes: business-friendly policies and low taxes for the rich, welfare reform and “tough love” for the powerless.

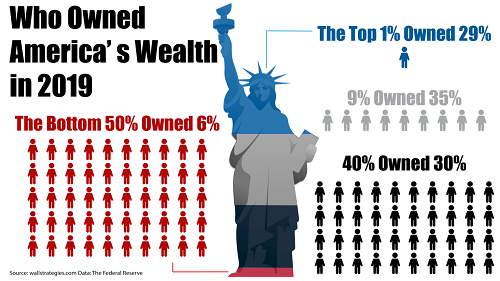

Today the fruits of forty years of neo-liberalism are plain to see. We have the greatest economic inequality in the history of modern democracies. In 2020, the three richest Americans commanded as much wealth as the poorest 150 million. We see a rapidly degrading biosphere, with humanity’s grossly unsustainable ecological footprint swiftly increasing. Normally staid scientists use words like ‘ghastly’ and ‘catastrophic’ to describe the environmental future humanity is inflicting on our descendants. Meanwhile, the democracies of the developed world creak and groan, providing little evidence that leaders or citizens are up to the task of creating more just and sustainable societies.

I’m not ready to give up working for a better future. But I think we need to consider more direct means for getting there, now that the complicated and indirect means we have been pursuing for the past half century have proven insufficient. The two policies I propose are first, taking substantial wealth directly from the rich and giving it directly to the poor, and second, creating significantly smaller national populations, on purpose, by incentivizing small families and providing free, universal access to effective modern contraception.

Share the wealth

To some degree, my first proposal has been a policy goal of progressive political parties for many years. Government programs providing universal health care, old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, government-financed child-care and the like, often have a substantial redistributive element. They have helped limit economic inequality throughout the developed world, while improving common people’s lives. But precisely because they can be effectively redistributive, rich people generally resist them, particularly strenuously in the United States. And because they have other goals besides redistribution, these policies can be (and sometimes should be) limited or reversed when they prove themselves inefficient in achieving these other goals.

The distribution of wealth in the United States

By wallstrategies.com ~ Click to enlarge

In response to this, liberal policymakers often devise more targeted policies with more modest goals. Such policies in the U.S. have become more complex in their criteria for access, yet more obscure in their criteria for success. The upshot has been policymaking too timid to achieve substantial economic redistribution and too complicated to develop a constituency among the people who might benefit from it. In addition, many progressive policymakers have become so convinced of their own cleverness and so divorced from the problems of their poorer fellow citizens that they are comfortable with continued failure. The bottom line is that economic inequality continues to grow throughout the developed world.

The first step to addressing this problem is to recognize excessive economic inequality itself as a fundamental problem. The problem isn’t (just) that poor people cannot provide themselves with A, B or C, or (just) that middle-class economic precariousness undermines people’s sense of well-being, or (just) that rich people use their wealth to undermine the democratic political process. All these particular problems can legitimately be addressed in various targeted ways. But for all these reasons and many more, excessive economic inequality is itself an evil. Arguably that evil can best be addressed directly, by transferring wealth from the rich to the poor. In doing so, all the other problems that wealth inequality leads to will be ameliorated, since there will be less of it.

Consider an annual wealth tax of 2% levied in perpetuity on all citizens with total assets over $5 million, increasing to 5% on all assets above $20 million. And then imagine that wealth not used to fund the latest government programs dreamed up by clever liberal policymakers (such as those now proposed by the Biden administration). Instead, imagine this wealth—a substantial sum in any developed country—liquidated and refunded in equal shares to the poorest 20% to 50% of a nation’s population to spend or save as they see fit. Such a program will ameliorate at least some of the problems of poverty and middle-class precariousness. It will reduce the power that vast wealth commands in our democracies, directly, by reducing concentrated wealth. Most importantly, it will create a large and powerful constituency for continued wealth redistribution.

The best thing about this “Robin Hood” proposal, or others like it, is that it recognizes the limits of human intelligence. Rather than assume policymakers can design and implement a thousand and one clever policies to solve a thousand and one difficult problems, it accepts that this asks too much of them. Politicians aren’t that smart—and neither is the general public. We can’t follow the details of tax policy, health care policy, industrial policy, etc., and tease out all the interests at stake. We can’t hold politicians accountable for their decisions in these areas, even when they affect us. Hence common people repeatedly lose out to the wealthy, whose accountants and lobbyists can keep track of these matters. But the average Joe or Jane could understand a simple tax and redistribution scheme of the kind I advocate—particularly with the annual reminder of a nice fat check.

In a capitalist system, wealth tends to concentrate and economic inequality tends to increase. If we want just societies with some measure of economic fairness, we will have to put in place effective measures to limit this concentration of wealth through its perpetual redistribution. These must include simple and effective measures that the public can understand and that the wealthy and powerful cannot avoid. If these are less efficient than the complex proposals of smarty-pants economists and policy-makers, so be it (although we should not take their word for this, since this greater efficiency is often illusory). Taxing the wealthy and giving the proceeds directly to the poor or middle class would preserve sufficient economic equality to uphold the moral and political equality to which modern democracies currently pay lip service. It would be an effective counter to the noxious power of concentrated wealth, strengthening the polities on which our descendants’ happiness will depend.

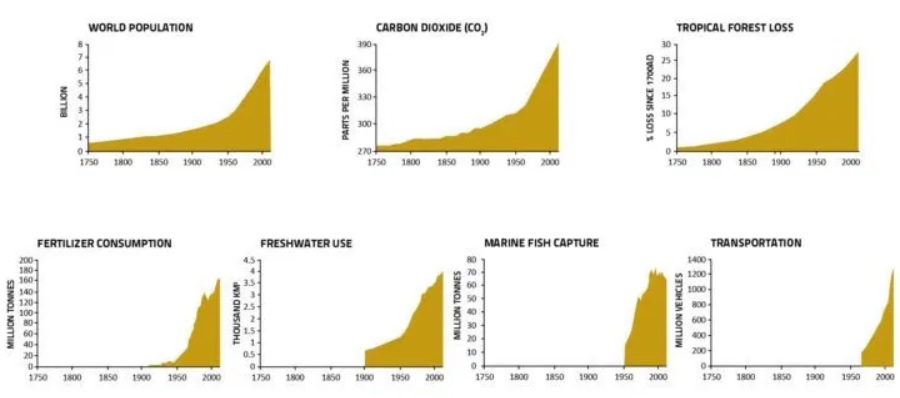

Shrink human numbers

As I reached adulthood in 1980, American environmentalism was coming off a decade of spectacular success. Many of the United States’ fundamental environmental laws were enacted during the 1970s, including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). While not perfect, these laws went a long way toward achieving their goals of reducing pollution, preserving species on the brink of extinction, and alerting citizens to the environmental costs of development. Yet since 1980, environmental progress has stalled and even reversed, at least in the US. As we are regularly reminded, the big environmental trends are uniformly negative. Greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, along with global temperatures and extreme weather events. Biological knowledge increases by leaps and bounds, but biodiversity itself is declining rapidly. The pollution and toxification of our lands and waters generally continues to worsen, although individual nations have beaten this trend in some areas.

Human Footprint

Source: United Nations, 2017 ~ Click to enlarge

No doubt the causes of these failures are complex. Part of the explanation is that once environmentalists faced problems that could only be solved by limiting economic or demographic growth, we lost our nerve and scaled back our commitments. As we shrank our goals, environmentalists embraced ever more complex and doubtful solutions. Both trends are well exemplified by today’s signature environmental problem: climate disruption. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the two main drivers of increased greenhouse gas emissions over the past half century have been population growth and increased wealth. But neither scientists, politicians, nor environmentalists have made limiting human numbers or the pursuit of wealth part of the fight against climate change. So the IPCC’s reports, nations’ climate action plans, and corporations’ sustainability initiatives discuss clever technological or managerial changes designed to reduce the emissions caused by growth, while never questioning growth itself.

Not surprisingly, little progress has occurred so far. Now, in response, corporate-sponsored scientists urge us to consider dangerous geoengineering schemes to radically change the composition of the atmosphere or the oceans. In other words: double down on human cleverness and on managing nature rather than ourselves. Anything but consider limits to growth. Proponents ignore the fact that such geoengineering projects, even if they worked, would worsen other environmental problems, such as ocean acidification, and would need to be continued in perpetuity. Defeated by the complexity of the “wicked problem” of climate change, they ask us to commit to much more complex and unlikely solutions, defending this approach as “realism” because it accepts the economic status quo.

The first step to successfully addressing our environmental problems is to realize that excessive human numbers are themselves a problem. It isn’t just that large and growing numbers lead to large and growing greenhouse gas emissions; that they lead to excessive habitat loss and degradation and hence fewer birds, mammals, insects, and other wild creatures; that more people leads to more plastic in the oceans, more fertilizers and pesticides on the land, more chemicals in the rivers. Excessive human numbers lead to all these problems and many more. Hence overpopulation is itself an environmental problem. Conversely, significantly fewer people would help decrease all humanity’s environmental demands on nature and make all our particular environmental problems easier to solve. Stabilizing and then decreasing national populations is thus necessary to create sustainable societies. Again, this can best be done by making substantially smaller populations an explicit policy goal and pursuing it directly.

The governments of developed countries should start by explaining to their citizens the many contributions smaller populations will make to achieving real sustainability. They should provide comprehensive sex education to all adolescents and ensure universal access to modern contraceptives for all their citizens. Since most developed nations already have fertility rates below replacement rate, in time such policies will lead to decreasing populations. These decreases could be accelerated by providing financial incentives to adults who forego childbearing or limit themselves to only one child. Nations could also reduce immigration, which currently prevents many developed nations from allowing their populations to decrease even though they have below-replacement fertility levels. At lower immigration levels, the US, Germany and France could all start to reduce their populations within a decade or two.

Like transferring wealth from the rich to the poor, reducing human numbers is a simple, direct solution that would help solve a myriad of problems. Fewer people is the environmental gift that keeps on giving. It helps with every environmental problem, from climate change to habitat loss to noise pollution to the spread of exotic species. Fewer people means less air and water pollution; more habitat and resources for other species. It opens up new opportunities for rewilding lands formerly devoted to agriculture and other human purposes. Importantly, it provides a greater margin for error when people make environmental mistakes.

Above all, this solution recognizes limits to human cleverness. Rather than assume policymakers can design and implement a thousand and one clever policies to solve a thousand and one difficult environmental problems (without creating new ones), it recognizes that this is beyond them. Instead, this approach pursues one key, achievable environmental goal—fewer people—that could help us achieve all the others. That wouldn’t mean ignoring clever techno-managerial efficiency efforts; instead, reducing our excessive populations could give such efforts a real chance to succeed. Such an approach would show true realism—not the false realism which pretends that people can re-engineer the world to accommodate our endless demands.

First things first

175 years ago, at the start of America’s industrialization, Henry David Thoreau wrote:

“I cannot believe that our factory system is the best mode by which men may get clothing. The condition of the operatives is becoming every day more like that of the English; and it cannot be wondered at, since, as far as I have heard or observed, the principal object is, not that mankind may be well or honestly clad, but, unquestionably, that the corporations may be enriched. In the long run men hit only what they aim at. Therefore, though they should fail immediately, they had better aim at something high”.

For a long time, the United States and other developed nations have been aiming primarily at increased wealth and rapid economic growth, and only secondarily at creating just and sustainable societies. This worked tolerably well for a while: developed nations did find ways to generate and share greatly increased wealth, although they sacrificed the health, well-being and even lives of many men and women in the process. But what made some sense in 1850, or even 1950, no longer makes any sense today. If we want to have just and sustainable societies, we will have to make that our primary goal and put economic aims in their proper, subordinate place. The two proposals I have discussed here would make a strong start toward doing so.