Like all government policies, population policies should respect human rights. But what does that mean in practice? Putting reproductive rights in the larger context of creating just and sustainable societies provides the best framework for answering that question correctly.

Issues concerning human rights loom large in population debates. On the one hand, opponents of family planning efforts often point to past human rights abuses, such as forced abortions under China’s “one child policy” and coerced sterilizations in India during its “national emergency” in the mid-1970s, to justify their opposition. Some others who tolerate or even approve of family planning believe that government programs that speak too enthusiastically about the environmental or social benefits of reducing population growth, or that set specific targets to reduce fertility, are prone to such abuses. From this angle, the main human rights concern around family planning is that it should not force people to have fewer children than they want to have, or punish them if they have more than the state wants.

On the other hand, proponents of family planning often note that most social pressure and government coercion, now as in the past, involves coercing women to have more children than they want to have, or than they would have if they were free to choose. From this perspective, providing family planning services, especially accessible and affordable contraception, is necessary to operationalize a basic human right to reproductive choice, which is key to achieving freedom and equality for women. From this perspective, lack of contraception availability is the key human rights concern, with hundreds of millions of women around the world desiring to avoid pregnancy but unable to access modern contraception due to poverty, war, social stigma, government strictures, or opposition from religious leaders or other men.

Environmentalists bring our own set of rights concerns to the table. Environmental degradation directly threatens many human rights taken for granted, such as sufficient food, water and shelter, and the right to basic physical security. It indirectly threatens all human rights, since they depend on a functioning social order (as per article 28 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) which in turn rests on essential ecosystem services which humanity is currently degrading (see the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). Beyond human rights concerns, other species arguably have a right to continued existence free from untimely anthropogenic extinction. All these rights may be threatened by human overpopulation.

The right against coercion discussed in the first two paragraphs above can be secured by increasing reproductive freedom, while those rights discussed in the third paragraph may not be. Many countries have in fact achieved near-universal access to contraception while avoiding government coercion in how it is utilized. There is no inherent conflict between increasing people’s freedom to have more children and their freedom to have fewer. But securing the environmentally-dependent rights discussed in the third paragraph depends on limiting human numbers, not on how those numbers are chosen, and there is no guarantee that maximizing reproductive freedom will end human population growth.

Large family sizes remain the desired norm in many countries and among some religious and ethnic groups, helping to drive continued global population growth. Current preferences for small families in other places and among other groups may change. Furthermore, it isn’t clear that merely ending population growth will limit human numbers sufficiently to secure ecological sustainability; the evidence, from global heating to dwindling wildlife populations to the toxification of Earth’s lands and waters, implies otherwise. Two recent studies suggest that 3 billion people might be sustainable globally, if societies made heroic improvements in their current modes of consumption and production (Lianos and Pseiridis 2015, Tucker 2019). The current global population is 7.8 billion and it is growing by 80 to 85 million annually.

Since all human rights are environmentally-dependent rights and securing them could be rendered impossible by overpopulation, any serious ethical analysis needs to consider the possibility that limiting reproductive rights might be necessary to secure a decent future for humanity (and other species). Such a conclusion should not be surprising: no rights are absolute and all rights find their proper scope and limits within a larger framework of human interests. Parents exercising their reproductive rights should avoid damaging the interests of future generations, or even their current children. Yet we should not assume that coercion is the best recourse for changing people’s behaviours. On many issues of personal and public health and welfare, from quitting smoking to road safety, public information campaigns have successfully reduced harmful behaviours. Family planning is no different: evidence from many parts of the world over the past half century shows that promoting the benefits of small families while making modern contraception widely accessible can lead to rapid, voluntary fertility declines. Thus we should remain open to the happy possibility that more freedom, combined with better understanding of the impacts of reproductive decisions, will solve our population problems.

*

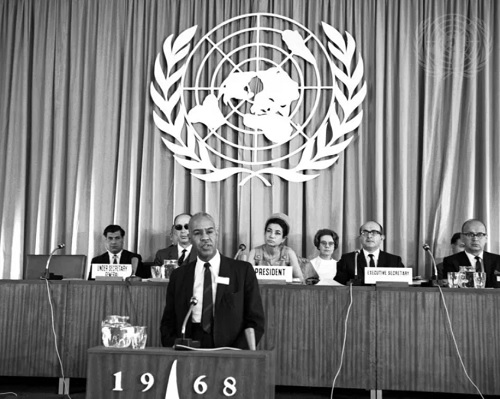

International human rights conventions and commitments provide a useful framework for thinking about these matters. The UN’s International Conference on Human Rights in Teheran in 1968 declared that “couples have a basic human right to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children” and that while sovereign nations were free to design their own population policies, those policies should pay “due regard to the principle that the size of the family should be the free choice of each individual family.” Meeting at the height of the global population explosion, however, delegates also “observed that the present rapid rate of population growth in some areas of the world hampers the struggle against hunger and poverty” and impedes efforts to provide people with adequate medical care, educational opportunities and other social services, “thereby impairing the full realization of human rights” and “the improvement of living conditions for each person.” They thus urged member states and concerned agencies “to give close attention to the implications for the exercise of human rights of the present rapid rate of increase in world population.” A clear inference was that going forward, excessive human numbers, or an excessive rate of increase in those numbers, could threaten human rights.

Roy Wilkins (United Stated), the Executive Director of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), speaking at

The International Conference on Human Rights in Teheran.

Photo by the United Nations.

The Teheran Declaration thus affirmed an important human right to decide one’s family size, while recognizing that the unbridled use of this right could be disastrous—economically, socially, and environmentally. This leaves scope for nations to enact policies to limit population growth to further their development, so long as they respect their citizens’ right to determine the size of their families. It also opens up the possibility of limiting that right, if necessary, to further the common good. Teheran thus provided a reasonable framework for thinking about rights and balancing them against one another and against other important human interests.

During the following 25 years, support and funding for international family planning aid peaked. Modern contraceptives became standard in much of the developed world, while many developing nations launched voluntary, successful family planning programs that brought average fertility down to or close to replacement rate. Support for family planning was widely shared by those focused on women’s rights, economic development and environmental protection, since they all believed that reducing population growth would advance their causes. Also during this time, however, serious abuses occurred in some national population programs, e.g. in India and China (TOP will discuss these in more detail in a forthcoming blog). This led to a backlash against family planning, in some quarters, and actions to safeguard against coercion were taken. The “Programme of Action” adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994 signaled shifts in the international approach to family planning which have continued into the present.

On the positive side, this new “Cairo consensus” reaffirmed and expanded earlier statements that family planning programs should avoid coercion and that “All couples and individuals have the basic right to decide freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children and to have the information, education and means to do so” (Cairo principle 8). It also affirmed with new clarity and greater detail that women were entitled to equal rights with men (principle 3), linking access to contraception more strongly with protecting women’s rights. Coming out of Cairo, the international community committed to a voluntary “rights-based family planning” paradigm that was less likely to contravene individuals’ right to have large families.

Gro Harlem Brundtland (the prime minister of Norway at the time) speaking at the

International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo.

Photo by the United Nations.

But during a decade when climate science made the connection between excessive human numbers and environmental degradation more obvious, Cairo helped obscure that connection. The Programme of Action talked bluntly about the need to “eliminate unsustainable patterns of production and consumption” (principle 6) but only indirectly about unsustainable patterns of reproduction. Principle 2 proudly proclaimed: “Human beings are at the centre of concerns for sustainable development. They are entitled to a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature.” But the need to limit our numbers in order to achieve such harmony was nowhere plainly affirmed.

Since 1994, international family planning discourse has thrown cold water on the notion that protecting the environment is an acceptable reason to support family planning efforts. If environmental benefits happened indirectly, fine, but family planning should only be justified because it would improve women’s lives and increase their agency; any other reason, such as environmental protection or even poverty alleviation, was seen as disrespectful of women and opening the door to coercion. This is actually a misreading of Cairo’s Programme of Action, which advocated responsible parenthood, in which parents “take into account the needs of their living and future children and their responsibilities towards the community” (paragraph 7.3). Similarly, setting specific goals for reducing fertility or increasing contraception use has been discouraged in recent decades, despite the Programme of Action’s affirmation that “demographic goals” were “legitimately the subject of government development strategies” (paragraph 7.12).

A positive view of these post-Cairo changes is that they “recognised the moral high ground occupied by those arguing in favour of the individual good and individual rights, as opposed to the social good” that concerned “Neo-Malthusian” environmentalists (DeJong 2000). A more accurate view is that the second part of “freely and responsibly” choosing family size was fading from view. Western feminists, like Westerners in general, had become better at asserting rights than affirming the responsible use of those rights, or balancing individual rights against the well-being of their communities. And Westerners, along with global Southerners, had lost sight of environmental limits to growth.

Summarizing these trends, former USAID Director for Population Steven Sinding (2008) wrote:

Cairo effectively signaled the end of the family planning movement and replaced it with what we know today as the reproductive health and rights movement, … What effectively ended at Cairo was the strong linkage between family planning services and efforts to reduce high birth rates.

I believe that without intending to do so, the architects of the Cairo consensus, as it is often called, transformed family planning from what had been seen as a global imperative to one among many desirable but nonessential public services. The crisis mentality that had sustained such high levels of support and so high a priority for family planning in the years before Cairo was no longer present at Cairo, and it has almost entirely disappeared in the years since Cairo.

Indeed, per capita financial support for international family planning efforts has declined substantially over the past three decades. This has played an important part in the slow fertility decline in poorer parts of the world, particularly in Africa, where many governments lack the will or the ability to fully fund such programs. But as Cairo’s Programme of Action and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals both emphasize, failure to provide access to contraception or secure the freedom to use it are themselves arguably human rights violations. Meanwhile the crisis of global environmental degradation continues apace, with all that implies for the ability of future societies to secure human rights.

*

Where does all this leave us? In a world where we want to maximize human freedom, but where people’s free choices regarding reproduction, food and energy consumption, and travel are heating up that world and destabilizing its climate. In this crowded and ecologically declining world, rights and responsibilities must come back together. In this world, no right can be unlimited, including the right to have children.

Perhaps the best practical way forward is for governments to protect and enhance the right of individuals and couples to choose their family size, while strongly encouraging them to choose small families. Coercion no, incentives yes. Forced sterilizations, no, frank reminders that we are overpopulated, yes. If most couples choose to have only one or two children, and few couples choose to have more, societies could end population growth relatively quickly and begin the necessary task of reducing their populations (assuming a willingness to limit immigration as well, a topic for another blog).

Even if the only right we were concerned about was the right to start a family, a case could be made for this balanced approach, since continuing the status quo threatens to create a world so environmentally degraded that our descendants cannot safely raise families. But of course, we want much more than this for our children and grandchildren. We want a world where they live securely in possession of the full gamut of human rights, as expressed in the SDGs. We want them to be able to flourish, not just exist, and to treat one another and the natural world more justly than we have managed to do. Such a future is possible—but only if we limit our numbers.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Philip Cafaro is professor of philosophy at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, Colorado, and an affiliated faculty member of CSU’s School of Global Environmental Sustainability. He holds degrees in philosophy and history from the University of Chicago, the University of Georgia, and Boston University. A former ranger with the U.S. National Park Service and a life member of the Sierra Club, Cafaro’s main research interests are in environmental ethics, population and consumption issues, and wild lands preservation. He is the author of Thoreau's Living Ethics: Walden and the Pursuit of Virtue and co-editor of the anthology Life on the Brink: Environmentalists Confront Overpopulation, both from University of Georgia Press, and author of How Many Is Too Many? The Progressive Argument for Reducing Immigration into the United States (University of Chicago Press).

|