COVID-19 is a horrible global crisis. Yet, like previous horrible global crises, including WWI and WWII, it also presents an opportunity and an obligation to rebuild our global society to adapt to changing conditions. The question is: what kind of change trajectory do we want? One comparable to WWI’s vindictive Treaty of Versailles or one more akin to the post WWII reconstruction of Europe, Japan, and the global economy.

The two postwar restructuring strategies were indeed very different from one another. The Treaty of Versailles attempted to reset society to the conditions before the war. Germany was held responsible for starting the war and the treaty imposed harsh penalties, including reparations payments, loss of territory, and forced demilitarization. The Treaty humiliated Germany while failing to resolve the underlying problems that had led to war in the first place. The economic chaos and public resentment it caused within Germany helped fuel the rise of the Nazi Party, which ultimately led to WWII.

The post WWII reconstruction of Europe, Japan, and the global economy, by contrast, included massive foreign aid programs aimed at supporting and rebuilding the defeated Axis powers in a more democratic, resilient and stable way. It also included the creation of the United Nations, the World Bank, and other global institutions aimed at ensuring peace, stabilizing trade, full employment, and promoting economic growth globally. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was enshrined as the key measure of progress toward these goals. This approach was the opposite of the vindictive Treaty of Versailles and led, in the end, to 70 years of relative peace and prosperity (the cold war and regional conflicts notwithstanding).

COVID-19 is a crisis similar in magnitude to the two 20th century world wars, albeit with very different causes, implications, potential responses, and resulting futures. The crisis has essentially shut down the global economy, is projected to kill hundreds of thousands, and it is presenting us with similar decisions about how to recover and rebuild. Do we try to restore the previous system as it was, like the Treaty of Versailles attempted to do, or do we rebuild in a better, more robust and resilient way, analogous to the positive, progressive agenda of the post WWII reconstruction? What would these two futures look like?

Build it back as before

There is not much imagination required for this vision. A return to business as usual would see all countries scrambling to catch up on the time “lost” during to the lockdown by adopting market-friendly reforms aimed at stimulating economic growth at all costs. Reacting to the demands of powerful industrial sectors, the crisis would allow government and corporate sector control over public life, relax environmental regulations and foster more competition among nation states and regions to acquire new competitive advantages in the race for growth. In the worst case, it could even turn into a ‘beggar thy neighbour’ scenario, similar to the interwar period, with increasing tensions across countries.

Even if a simple restoration of globalization, as we had in the 1990s, were possible, a return to business as usual would not be able to address the massive and growing inequality, the frayed social safety nets, the oligarchic control of governments, the rapidly worsening climate emergency, the accelerating loss of natural capital and ecosystem services, and the general loss of system resilience, which have marked the past few decades. Like the Treaty of Versailles, an attempt to simply go back to the way things were before the crisis will be counterproductive in the end. The world has changed massively in the second half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st. We are now solidly in the “Anthropocene” epoch[1] where human global interdependence with each other and the rest of nature can no longer be ignored. If we do not use this horrible crises to make the long overdue changes needed to build a sustainable and desirable future, we can expect even bigger crisis in the future.

Build it back better – to a sustainable wellbeing economy

There is also no shortage of visions of what is needed to transform the system. What is lacking is the political will to escape our addiction to the current system and make the necessary transformative changes. Has the COVID-19 crisis shaken the system sufficiently to allow the necessary changes to occur? Can we reboot our outdated operating system to one that can account for the new conditions of the Anthropocene?

The post WWII reconstruction enabled a radical restructuring of the world. It swept in many of the ideas included in Franklin Roosevelt’s proposal for a “Second Bill of Rights,” proposed during his State of the Union address in January 1944, after the tide of WWII had turned in the Allies’ favour. Roosevelt argued that the first US Bill of Rights had “proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness”. His remedy was to declare the need for an “economic bill of rights”. His text still resonates today:

“We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. “Necessitous men are not free men.” People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made. In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident. We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all—regardless of station, race, or creed.

Among these are:

- The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

- The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

- The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

- The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

- The right of every family to a decent home;

- The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

- The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

- The right to a good education.”

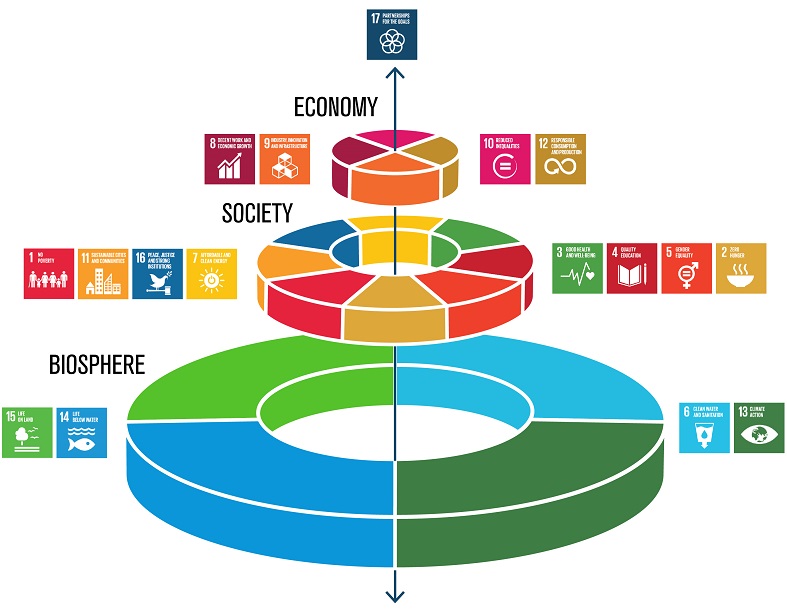

Roosevelt’s list of rights was a predecessor to the UN’s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights[2] and the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s)[3], which were adopted by all UN member states in 2015 (Figure 1). The SDGs include eliminating hunger and poverty, reducing gender and overall inequality, clean energy and water, adequate jobs and housing, good health and education, responsible consumption, urgent climate action and protection of the biosphere, and global peace and justice. For example, the EU Green Deal[4] and the US Green New Deal[5] incorporate proposals that address many of these rights and goals.

Changes needed

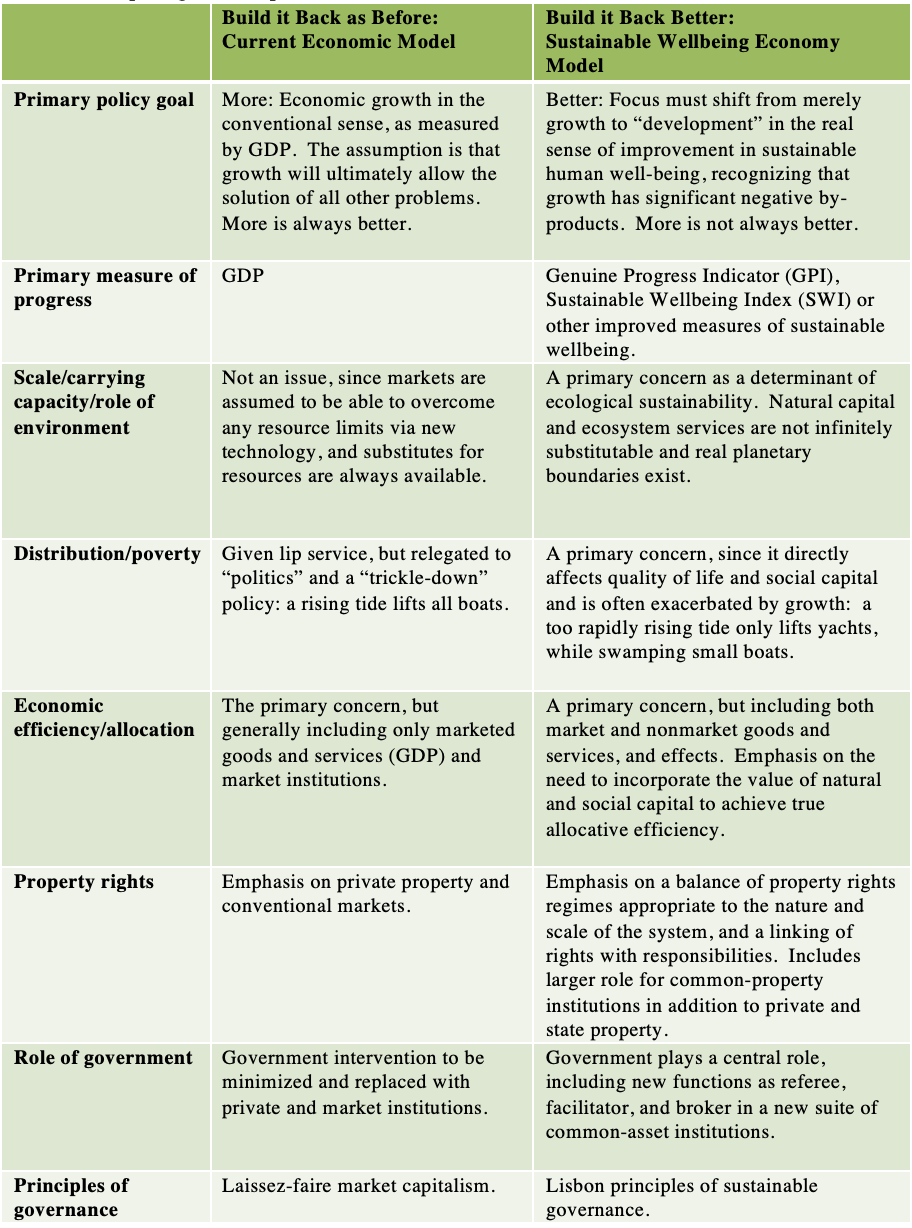

Similar major changes in vision and policies are necessary now to transform to a sustainable and desirable future for humans and the rest of nature (see also Table 1). These ideas are not new and are not ours alone. Many individuals, groups, NGO’s, businesses, and even a few vanguard governments have been recommending such changes.

Rebuilding after the COVID-19 crisis will require intelligent short term investments and careful attention to the transition. Obviously, no set of policy recommendations will work for all countries and the transitions must be managed in a just and transparent way.

The crisis also demands that we finally act on the longer-term changes to the system needed to achieve the SDGs and create a sustainable and desirable future. The Club of Rome[6] and The Wellbeing Economy Alliance (WEAll)[7] are ongoing initiatives to coordinate and amplify all of these efforts. Under the auspices of WEAll, the Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEGo)[8] coalition has started with the initial participation of Scotland, New Zealand and Iceland.

The current neoliberal economic paradigm that has dominated national and global reforms since the late 1970s emphasizes financial deregulation, privatization of healthcare and education, labour market flexibility, and trade liberalization. It was devised prior to an understanding of planetary boundaries or the emerging science of wellbeing. Believing that markets are self-correcting, and that individuals are rational actors mainly devoted to increasing their own (material) utility, neoliberalism has not only ushered in the greatest inequality and ecological destruction humankind has ever known, but also failed to promote psychosocial wellbeing. Without a new economic paradigm, we will continue down an unsustainable and undesirable path. The post WWII growth economy was far better than another World War, especially when the world was relatively empty and we knew less about the impacts of uncritical growth. However, times have changed, and, like during the post WWII reconstruction, we need to embrace a bold new direction to create a better world.

To make the transition to a just and sustainable wellbeing economy will require[9]:

- a fundamental change of worldview to one that recognises that we live on a finite planet and that sustainable well-being requires more than material consumption;

- replacing the present goal of limitless growth with goals of material sufficiency, equitable distribution, and sustainable human well-being; and

- a redesign of the world economy that preserves natural systems essential to life and well-being and balances natural, social, human, and built assets.

The dimensions of the new wellbeing economy include, but are not limited to:

Sustainable scale: Respecting ecological limits

- Establishment of systems for effective and equitable governance and management of the natural commons, including the atmosphere, oceans, and biodiversity.

- Creation of cap-and-auction systems for basic resources, including quotas on depletion, pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions, based on basic planetary boundaries and resource limits.

- Consuming essential non-renewables, such as fossil fuels, no faster than we develop renewable substitutes.

- Investments in sustainable infrastructure, such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, public transit, watershed protection measures, green public spaces, and clean technology.

- Promotion of regenerative agriculture, stronger regulation of factory farming, and a ban on wild animal eating and trading.

- Dismantling incentives towards materialistic consumption, including banning advertising to children and regulating the commercial media.

- Linked policies to address population and consumption.

Fair distribution: Protecting capabilities for flourishing

- Guaranteed fulfilling employment or income, and more balanced leisure-income trade-offs.

- Reducing systemic inequalities, both internationally and within nations, by improving the living standards of the poor, limiting excess and unearned income and consumption, and preventing private capture of common wealth.

- Establishment of a system for effective and equitable governance and management of the social commons, including cultural inheritance, financial systems, and information systems like the Internet and air waves.

- More progressive taxation, elimination of tax havens, taxing speculative financial transactions, and broader use of common asset trusts and sovereign funds.

Efficient allocation: Building a sustainable macro-economy

- Use of full-cost accounting measures to internalize externalities, value nonmarket assets and services, reform national accounting systems, and ensure that prices reflect actual social and environmental costs of production.

- Fiscal reforms that reward sustainable and well-being-enhancing actions and penalize unsustainable behaviours that diminish collective well-being, including ecological tax reforms with compensating mechanisms that prevent additional burdens on low-income groups.

- Systems of cooperative investment in stewardship (CIS) and payment for ecosystem services (PES).

- Increased financial and fiscal prudence, including greater public control of the money supply and its benefits and other financial instruments and practices that contribute to the public good.

- Ensuring availability of all information required to move to a sustainable economy that enhances well-being through public investment in research and development and reform of the ownership structure of copyrights and patents.

The ongoing COVID-19 crisis may have a silver lining if it opens the door for the long overdue transition to a world focused on the sustainable wellbeing of humans and the rest of nature – the world we all want.

Table 1. Comparing the two possible futures[10]

Figure 1. The 17 SDGs, recognizing the embeddedness of the economy in society

and the rest of nature (Source: Stockholm Resilience Centre).

References

[1] Steffen, W., Crutzen, P.J. and McNeill, J.R., 2007. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 36(8), pp.614-621.

[2] https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

[3] https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-d...

[5] https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/109/text

[6] https://clubofrome.org/

[7] https://wellbeingeconomy.org/

[8] https://www.gov.scot/groups/wellbeing-economy-governments-wego/

[9] Costanza, R., G. Alperovitz, H. Daly, J. Farley, C. Franco, T. Jackson, I, Kubiszewski, J. Schor, and P. Victor. 2013. Building a Sustainable and Desirable Economy-in-Society-in-Nature. ANU Press, Canberra, Australia.

[10] Costanza, R., Cumberland, J.H., Daly, H., Goodland, R., Norgaard, R.B., Kubiszewski, I. and Franco, C., 2014. An introduction to ecological economics. CRC Press.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Robert Costanza is Chair of Public Policy at the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University. He has authored or coauthored over 350 scientific papers, and reports on his work have appeared in Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report, The Economist, The New York Times, Science, Nature, National Geographic, and National Public Radio.

Associate Professor at Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University. Prior an Assistant Research Professor and Fellow at the Institute for Sustainable Solutions, at Portland State University. Awarded the Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) to do ‘An Integrative Assessment of Factors Contributing to Wellbeing in Australia.’. Ph.D. (Natural Resources), University of Vermont, VT, USA. M.A. (Energy and Environmental Analysis), Boston University, MA, USA. B.A. (Astronomy and Physics), Boston University, MA, USA

Other authors: Kate Pickett, Katherine Trebeck, Roberto De Vogli, Kristín Vala Ragnarsdóttir, Hunter Lovins, Lorenzo Fioramonti, Enrico Giovannini, Jacqueline McGlade, Lars Fogh Mortensen, Debra Roberts, Stewart Wallis, Richard Wilkinson

|