The world is faced with a grave

predicament, yet one rarely spoken

of. The United Nations (UN), almost

all governments, business, media and

both the political ‘left’ and ‘right’ are busy

extolling endless growth. Yet we live on a finite

planet, so clearly endless economic growth

is impossible, and its pursuit unsustainable

and unethical – indeed, such destructive

pursuit of the impossible is insane. There

are three main drivers of ‘unsustainability’

– overpopulation, overconsumption and

the growth economy (Washington, 2015).

We feel it is time to focus on these. These

points have been made in the past, but for

quite some time the reasons behind the

unsustainability and insanity of endless

growth have not been explored. We feel

society (and academia) need to be regularly

reminded of them.

The question “On a finiteplanet, is it possible

to keep growing economically forever?”

is one hardly ever asked in neoclassical

economics (Daly, 1991; 2014) or in many other

academic disciplines (Washington, 2015).

Even the World Commission on Environment

and Development (1987) report Our Common

Future did not ask that question – suggesting

that ‘sustainable development’ required a

gross domestic product growth rate of 5%

(a rate at which the global economy would

double its output every 14 years).

More recently, the UN Environment

Programme (2011: 2) has promoted the idea

of the ‘green economy’, which it describes as

“a new engine of growth” (our emphasis). The

UN Sustainable Development Goals (available

at http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/)

also fail to acknowledge that endless growth

is impossible and its pursuit fundamentally

unsustainable (Kopnina, 2016b).

Ecological Limits

This obsession with endless economic

growth demonstrates that societies

still do not understand that humanity

has exceeded ecological limits, and

that this is the root cause of the current

environmental crisis. The book Limits

to Growth (Meadows et al., 1972) showed

that human population growth and the

concomitant increase in the consumption

of resources would exceed planetary limits

around the middle of the 21st century,

causing societal collapse. Upon its release,

this report was strongly criticized by

traditional economists, who labelled the

authors ‘prophets of doom’ (Solow, 1973).

However, a recent 40-year review of Limits

to Growth has shown that its models are

remarkably accurate (Turner, 2014). To

summarize key environmental indicators

of ecological overshoot:

The Global Ecological Footprint now stands at 1.6 Earths (Global Footprint Network, 2017).

The Living Planet Index has declined by 58% between 1970 and 2012 (WWF, 2016).

The species extinction rate is at least 1000 times normal (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005).

At least 60% of ecosystem services are degrading or being used unsustainably (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment,

2005).

Four of nine planetary boundaries have now been exceeded as a result of human activity (Steffen et al., 2015).

In effect, we are bankrupting nature and

consuming the past, present and future of

our biosphere (Wijkman and Rockström,

2012). On a finite world with expanding

human population and consumption,

clearly something has got to give.

Humanity faces a fundamental problem,

for it is totally dependent on the biosphere

it is degrading (Washington, 2013). Hence

society needs to understand and accept

that we are way past sustainable ecological

limits.

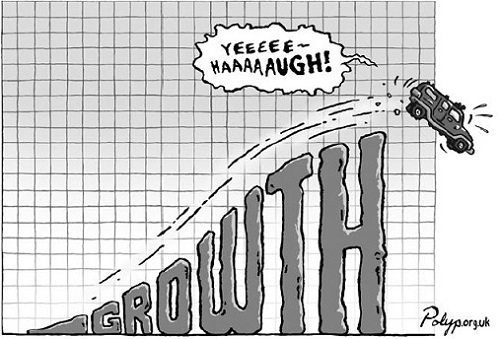

The Endless Growth Mantra

Environmental science may tell us that the

consumer society is on a self-destructive

path, but many of us successfully deflect

the evidence by repeating in unison

the mantra of perpetual growth (Rees,

2008). Yet endless repetition does not

make something true. Daly (1991: 183)

pointed out that economic growth is

unrealistically held to be “the cure for

poverty, unemployment, debt repayment,

inflation, balance of payment deficits, the

population explosion, crime, divorce and

drug addiction.” This has not changed

much in the 25 years since Daly wrote those

words, and economic growth is still widely

seen as the panacea for almost all societal

ills. Sometimes commitment to growth

may be promoted in the guise of ‘free

trade’, ‘competitiveness’, ‘productivity’

– or even as ‘sustainable development’

(Victor, 2008). Indeed, from its coining in

Our Common Future to now, ‘sustainable

development’ has had its meaning largely

coopted to mean ‘sustainable growth’ – a

phrase which, we suggest, is an oxymoron

(Washington, 2015). World leaders seek

growth above all else. Neoclassical

economics claimed that the benefits of

growth would ‘trickle down’ and alleviate

global poverty, but this has failed (Kopnina

and Blewitt, 2015). As Daly (1991) notes,

the verb ‘to grow’ has become twisted;

we have forgotten its original meaning: to

spring up and ‘develop to maturity’. That

is, in nature, growth gives way to maturity,

a steady state. To grow beyond a certain

point can be disastrous.

“We are bankrupting nature and consuming the past, present and future of our biosphere.”

|

A final aspect of growthism is that it is

commonly claimed that “economic growth

is necessary if we are to have jobs.” Is this

claim correct? There are good grounds to

question whether jobs have historically

been linked to growth. Victor (2008) notes

that the idea only developed 60 years ago,

and for most of human history we managed

to provide employment without economic

growth. Does growth necessarily bring

employment in any case? For example,

there were more Canadians with incomes

less than the ‘low Income cut-off’ in 2005

than in 1980, despite real Canadian gross

domestic product having nearly doubled

over that period (Victor, 2008). As Victor

(2008) notes, it is possible to develop

scenarios where full employment prevails,

poverty is eliminated, people have

more leisure, and greenhouse gases are

drastically reduced, in the context of low

– and ultimately no – economic growth. It

is thus mistaken to assume that economic

growth is a necessity for full employment.

Indeed, once we have exceeded ecological

limits, growth will make us worse off. We

have then reached uneconomic growth

(Daly, 2014). However, unless there are

changes in social outlook, our experience

of diminished well-being will be blamed

on ‘product scarcity’. The orthodox

economic and policy response will then be

to advocate increased growth to remedy

this. In the real world of ecological limits,

this will make us even less well off, but

this will in turn lead to advocacy of ‘even

more growth’ (Daly, 1991). This becomes

a death spiral. Healing our world requires

accepting the reality that the economy

cannot grow forever. However, in recent

years the concept of decoupling has been

put forward to argue that it is possible to

have continued economic growth without

producing further environmental damage.

Decoupling

‘Decoupling’ refers to the idea that an

economy can continue to increase its output

of goods and services, without thereby

increasing pressure on the environment

– for example, by shifting to renewable

energy sources, and using efficiencies to

reduce the amount of resources and energy

consumed. Reducing the use of energy

and materials by society is certainly

needed, and some claim we can move to

a ‘Factor 5’ strategy and only use 20% of

the energy and materials we currently use

(von Wiezsäcker et al., 2009), whilst still

retaining our current quality of life. The

problem with this approach is that the very

concept of decoupling suggests we can

keep on growing forever. As noted above,

the UN advocates the ‘green economy’ yet

also sees this economy as “a new engine

of growth” (United Nations Environment

Programme, 2011: 2); this combination of

‘green’ and ‘growth’ is only made plausible

by invoking the idea that it is possible to

completely decouple economic growth

from environmental impacts.

“Attempts at decoupling slow down the rate at which things get worse, but do not turn them around.”

|

How successful have we been in

decoupling? Some modest decoupling of

material flows occurred from the mid1970s

to mid-1990s, but total material

throughput in the global economy still

increased. Victor and Jackson (2015)

note that while there has been some

‘relative decoupling’, any serious absolute

decoupling is not evident. At best, as Victor

(2008) notes, attempts at decoupling slow

down the rate at which things get worse,

but do not turn them around. Hence, talk

of ‘100% decoupling’ is likely to be merely

wishful thinking that allows business-as-

usual growth to continue. Indeed, focusing

our attention on the idea of decoupling

runs the risk of becoming part of the denial

of the unsustainability of endless growth.

Denial

How is it possible for civilizations to

be blind towards the grave and rapidly

approaching threats to their survival,

even when the evidence for those threats

is extensive (Brown, 2008)? Humanity

has a key failing – we tend to deny our

problems. Humanity denies some things

because they force us to ‘confront change’,

others because they are just too painful, or

make us afraid. This human incapacity to

hear bad news makes it hard to solve the

environmental crisis. Of course, another

source of this denial is ideological, where

the reality of the environmental crisis

is denied owing to neoliberal hatred of

any regulations that could restrict the

activities of business (Oreskes and Conway,

2010). The result of such denial is that, as

a society, we continue to act as if there is

no environmental crisis, no matter what

the science says (Washington, 2017a).

Perhaps the key form that denial takes in

the public realm is simply silence – thus

the silence about the environmental crisis;

the silence about the fact that the world

is overpopulated; the deafening silence

about the impossibility of endless growth

(Washington, 2015).

In the past, denial of ecological limits

was common in neoclassical economists.

However, such denial of reality is not just a

thing of the past. An Ecomodernist Manifesto

(available at http://www.ecomodernism.org/)

was written in 2015 by eighteen professionals,

ten of whom are academics. The manifesto

claims:

Despite frequent assertions starting in the

1970s of fundamental “limits to growth”,

there is still remarkably little evidence that

human population and economic expansion

will outstrip the capacity to grow food or

procure critical material resources in the

foreseeable future […] To the degree to

which there are fixed physical boundaries

to human consumption, they are so

theoretical as to be functionally irrelevant.

Such a dismissal of ecological limits (and

the rapidly worsening environmental crisis)

indicates many in academia are still in

denial of the insanity and unsustainability

of endless economic growth.

Anthropocentrism versus Ecocentrism

Many things change (and solutions become

easier) if we change our worldview and

ethics. As Donella Meadows (1997: 84) notes:

People who manage to intervene in systems

at the level of a paradigm hit a leverage

point that totally transforms systems

[…] In a single individual it can happen in

a millisecond. All it takes is a click in the

mind, a new way of seeing.

It has only been possible for our societies

to maintain a belief in the desirability of

pursuing endless growth, because of the

dominant anthropocentric worldview of

modernism (Curry, 2011), which sees the

world as no more than a resource for human

use (Crist, 2012). To put this another way,

the obsession with endless growth has

been the offspring of the anthropocentric

‘human chauvinism’ and ‘speciesism’ that

has dominated Western society for at least

the last 200 years.

“It has only been possible for our societies to maintain a belief in the desirability of pursuing endless growth, because of the dominant anthropocentric worldview of modernism.”

|

In contrast, an ecocentric worldview finds

intrinsic value in nature (Washington et al.,

2017). It holds, as Daly (1991: 248) notes, that

“there is something fundamentally wrong

in treating the Earth as if it were a business

in liquidation.” Society thus needs to return

to ecocentrism and adopt an Earth ethic

(Rolston, 2012) and undertake the ‘Great

Work’ of repairing the Earth (Berry, 1999) to

enter the ‘Ecozoic’ (Swimme and Berry, 1992).

Changing to a worldview of ecocentrism is

thus the key step on the path to a sustainable

future (Washington et al., 2017).

Solutions

A major problem with tackling the

environmental crisis is the distraction

caused by partial solutions. For example,

we acknowledge the need for the

maximum possible ‘decoupling’ as part

of a circular or green economy, one that

massively reduces society’s use of energy

and materials (Kopnina and Blewitt,

2015). However, such savings should not

be seen as ‘a new engine of growth’, nor

will such savings be long-term solutions

if we fail to address overpopulation and

overconsumption. The plain truth is that

partial solutions are only of value if they

are part of a comprehensive move to

abandon endless economic growth. We

suggest the following solution frameworks

(Washington, 2015):

accept ecological reality and roll back

denial;

adopt an ecocentric worldview (inspired

by a sense of wonder at life), where we

abandon the false anthropocentric

dream of ‘mastery of nature’.

These are the overarching changes in our

mindset that we must make. Within them

are the practical strategies, including:

controlling population growth through

education, family planning and non-

coercive, humane strategies (Engelman, 2016);

rolling back the deliberately constructed

consumer ethic (Assadourian, 2013) and

concurrently adopting a ‘cradle to cradle’

approach (Kopnina and Blewitt, 2015);

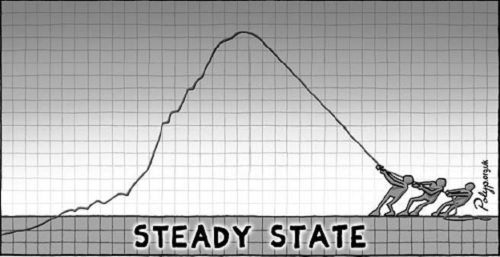

moving past growthism to a steady-state

economy (Daly, 2014);

solving climate change urgently, focusing

on mitigation;

adopting of ‘appropriate’ technology,

especially 100% renewables within two

to three decades, concurrently with

major drives for energy efficiency and conservation;

reducing poverty and inequality, while

simultaneously supporting the Nature

Needs Half vision (Kopnina, 2016a);

educating effectively for sustainability

based on ecological reality and ecocentrism;

creating the political will for change.

Change is urgently needed, and is certainly

feasible. The key to this is breaking the silence

of denial, by talking about the problems.

This may sound wishy-washy, but in fact

meaningful dialogue on the impossibility of

endless growth is an essential step. Academia

can (and should) lead the way on this.

Solving the key cause of the problem – the

idea we can have endless economic growth

on a finite planet –

means tackling the three

key drivers of unsustainability (Washington,

2015): overpopulation, overconsumption and

growth-focused economic policy.

“The steady-state economy deals with all three key drivers of ecological unsustainability, plus a key driver of social

unsustainability: inequality of income.”

|

However, this also means tackling some

of the biggest taboos in society. First,

many in society still consider discussion

of limiting the human population a

taboo, but we cannot afford to have this

remain an ‘undiscussable’. Secondly,

Western society (globalized around the

world) is a ‘consumer culture’ that has

been deliberately constructed since 1950;

and what was deliberately constructed

can also be deconstructed (Assadourian,

2013). Thirdly, the growth economy is

still espoused by the UN and almost all

national governments. However, a rational

(and ethical) solution has been espoused

by ecological economist Herman Daly

since the 1970s: the steady-state economy

(Daly, 1991; Daly, 2014). A steady-state

economy features a sustainable population

size for the carrying capacity of its region,

low resource use and a distribution of

wealth which is fair and equitable on an

intergenerational basis (Daly, 2014).

The transition path to a steady-state

economy will be made up of many small

‘positive steps’ that society can take

(Washington, 2017b). The steady-state

economy deals with all three key drivers

of ecological unsustainability, plus a key

driver of social unsustainability: inequality

of income. The scale of income inequality

as a problem can be understood from the

fact that the wealthiest 10% of the world’s

population now owns approximately

85% of the world’s wealth (Credit Suisse,

2016). The ‘cradle to cradle’ approach (and

the related circular economy) arguably

offer the most hope to cut resource use

(Kopnina and Blewitt, 2015). However, we

feel that ways forward can only be found if

the steady-state economy and the circular

economy (within the former) are adhered

to in strict terms and practice. That means

that they must not be subverted to become

partial solutions used to encourage further

growth.

As remarked above, to enable these

changes, what is needed is a major

paradigm shift from anthropocentric

modernism to ecocentrism (Washington

et al., 2017). We acknowledge that the

scale of our predicament is huge, but

maintain that solutions are possible if we

overcome the denial that currently blocks

them. Now, accepting the reality of our

predicament can be depressing. Hence the

need to discuss statements such as: “It is

too late.” The danger of such statements

is that they tend to become self-fulfilling

prophecies, as they give people an excuse

to go into despair, and do nothing positive

(Washington, 2015). In fact, every action

we take towards a ‘Great Work’ of repairing

the Earth (Berry, 1999) is useful. So it is

never too late. Some actions, indeed, may

fail, but some may help to turn the tide – a

‘great tide’ of rising action (Moore, 2016).

Conclusion

The insanity and unsustainability of

endless economic growth is a critical

reality that society must acknowledge

and discuss. To ignore this is irrational

and self-destructive. Ecological limits

exist and have been exceeded. Yet society

remains locked into the unsustainable

mantra of endless growth that has caused

the environmental crisis. Most government

and business response to this has been to

undertake partial solutions, while at the

same time denying the central cause – our

addiction to endless growth. Our ability

to deny our predicament is aided by the

dominant worldview of anthropocentric

modernism. Hence we face a difficult

predicament, for the global experiment of

endless growth has well and truly failed,

and destructively so.

“The insanity and unsustainability of endless economic growth is a critical reality that society must acknowledge and discuss. To ignore this is irrational and self-destructive.”

|

Change is not easy but it is possible, but

only by accepting the nature and scale of

our predicament. If we break the silence

of denial, then everything becomes easier.

The other great game-changer is changing

our worldview from anthropocentrism to

ecocentrism. We can then move to slow (then

stop) growth in population, and minimize

resource use via a steady-state economy.

We can stop global ecocide, improve social

equality and move to a truly sustainable

future. Then, this era could become, not the

egotistical ‘Anthropocene’, but the start of

the sustainable ‘Ecozoic’. That is a worthy

vision for the 21st century, a ‘Great Work’

we can all help bring to reality.

References

Assadourian E (2013) Re-engineering cultures to create

a sustainable civilization. In: Starke L, ed. State of the

World 2013: Is sustainability still possible? Island Press,

Washington, DC, USA: 113–25.

Berry T (1999) The Great Work: Our way into the future.

Bell Tower, New York, NY, USA.

Brown D (2008) The ominous rise of ideological

think tanks in environmental policy-making. In:

Soskolne C, ed. Sustaining Life on Earth: Environmental

and human health through global governance. Rowman

and Littlefield, Lanham, MD, USA: 243–56.

Crist E (2012) Abundant Earth and the population

question. In: Cafaro P and Crist E, eds. Life on the

Brink: Environmentalists confront overpopulation.

University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA, USA: 141–51.

Credit Suisse (2016) Global Wealth Report 2016.

Credit Suisse, Zurich, Switzerland. Available at

https://is.gd/JJyEjg (accessed February 2018).

Curry P (2011) Ecological Ethics: An introduction (2nd

edition). Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

Daly H (1991) Steady State Economics. Island Press,

Washington, DC, USA.

Daly H (2014) From Uneconomic Growth to a Steady State

Economy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

Engelman R (2016) Nine population strategies to stop

short of nine billion. In: Washington H and Twomey

P, eds. A Future Beyond Growth: Towards a steady state

economy. Routledge, London, UK: 32–42.

Global Footprint Network (2017) World Footprint: Do we

fit the planet? Global Footprint Network, Oakland,

CA, USA. Available at https://is.gd/rUTqiT (accessed February 2018).

Kopnina H (2016a) Half the earth for people (or more)?

Addressing ethical questions in conservation.

Biological Conservation 203: 176–85.

|

“Ecological limits exist and have been exceeded. Yet society remains locked into the unsustainable mantra of endless growth that has caused the environmental crisis.”

|

Kopnina H (2016b) The victims of unsustainability:

A challenge to sustainable development goals.

International Journal of Sustainable Development &

World Ecology 23: 113–21.

Kopnina H and Blewitt J (2015) Sustainable Business: Key

issues. Routledge, London, UK.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) Living Beyond

our Means: Natural assets and human wellbeing. United

Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya.

Available at http://www.millenniumassessment.org (accessed February 2018).

Meadows D (1997) Places to intervene in a system:

In increasing order of effectiveness. Whole Earth (Winter): 78–84.

Meadows D, Meadows D, Randers J and Behrens W (1972)

The Limits to Growth. Universe Books, Washington, DC, USA.

Moore K (2016) Great Tide Rising. Counterpoint, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Oreskes N and Conway M (2010) Merchants of Doubt:

How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues

from tobacco smoke to global warming. Bloomsbury

Press, New York, NY, USA.

Rees W (2008) Toward sustainability with justice: Are

human nature and history on side? In: Soskolne C,

ed. Sustaining Life on Earth: Environmental and human

health through global governance. Rowman and

Littlefield, Lanham, MD, USA: 81–93.

Rolston H III (2012) A New Environmental Ethics: The next

millennium for life on Earth. Routledge, London, UK.

Solow R (1973) Is the end of the world at hand? Challenge 16: 39–50.

Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockström J et al. (2015)

Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development

on a changing planet. Science 347: 1259855.

Swimme B and Berry T (1992) The Universe Story: From

the primordial flaming forth to the Ecozoic era. Harper

Books, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Turner G (2014) Is Global Collapse Imminent? An updated

comparison of The Limits of Growth with historical

data (research paper 4). Melbourne Sustainable

Society Institute, Parkville, VIC, Australia. Available

at https://is.gd/8dtsWW (accessed February 2018).

United Nations Environment Programme (2011)

Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to sustainable

development and poverty eradication. United Nations

Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya. Available

at http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy (accessed

February 2018).

Victor P (2008) Managing without Growth: Slower by

design, not disaster. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

Victor P and Jackson T (2015) The trouble with growth.

In: Starke L, ed. State of the World 2015: Confronting

hidden threats to sustainability. Worldwatch Institute,

Washington, DC, USA, 37–50.

von Weizsäcker E, Hargroves K, Smith M et al. (2009)

Factor 5: Transforming the global economy through

80% increase in resource productivity. Earthscan, London, UK.

Washington H (2013) Human Dependence on Nature:

How to help solve the environmental crisis. Earthscan, London, UK.

Washington H (2015) Demystifying Sustainability:

Towards real solutions. Routledge, London, UK.

Washington H (2017a) Denial – the key barrier

to solving climate change. In: DellaSala DA and

Goldstein MI, eds. Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene. Elsevier, London, UK, 493–9.

Washington H, ed (2017b) Positive Steps to a

Steady State Economy. NSW Chapter of the

Center for the Advancement of a Steady State

Economy, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Available at

https://is.gd/UkMOiY (accessed February 2018).

Washington H, Taylor B, Kopnina H et al. (2017) Why

ecocentrism is the key pathway to sustainability.

The Ecological Citizen 1: 35–41.

World Commission on Environment and Development

(1987) Our Common Future. Oxford University Press, London, UK.

Wijkman A and Rockström J (2012) Bankrupting

Nature: Denying our planetary boundaries. Routledge, London, UK.

WWF (2016) Living Planet Report 2016: Risk and resilience

in a new era. WWF International, Gland, Switzerland.

Available at https://is.gd/rcbOx9 (accessed February 2018).

|

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Haydn Washington is an environmental scientist, writer and activist based at the PANGEA Research Centre, UNSW, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Helen Kopnina is an environmental anthropologist at Leiden University, Leiden, and The Hague University of Applied Science, The Hague, the Netherlands.

|