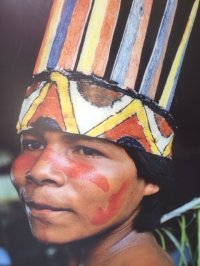

A rich cultural diversity exists in the Pan-Amazonia region with nearly 400 indigenous cultures.

A rich cultural diversity exists in the Pan-Amazonia region with nearly 400 indigenous cultures.

|

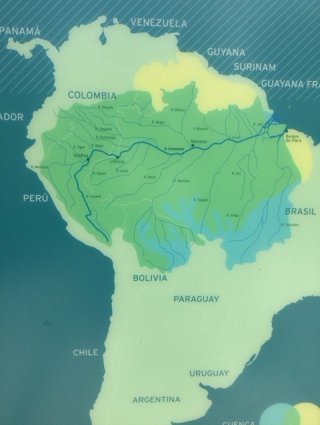

Pan-Amazonia is a territory that encompasses areas of nine countries with seven million square kilometers and covers a third of all of South America. The future of the planet depends a lot on the Amazon basin. The future of all human beings also depends on our taking care of these living spaces, these forests, these waters, but above all, the wealth and knowledge of its peoples.

This region is profoundly affected by the search for oil and gas, illegal logging, the rapid expansion of livestock and agriculture, and uncontrolled extraction of natural resources.

Throughout the last decades, a series of transformations took place in the territory due to resource production activities. In 1890, there was the rubber extraction and a second boom in the 1940s of this raw material, the fascination with skins and plants in 1960, the boom of wood in 1970, and between the ‘80s and ‘90s was the coca and drug trafficking. And from 2008 until today, the economic model of extractives has intensified, characterized by industrialization with infrastructure works such as hydroelectric power, roads, ports, among others. There is also illegal fishing and the extraction of gold and minerals that pollute the environment and alter the health of populations.

The intensity of the economic projects in the Amazon seriously threatens the lives of its inhabitants. At the same time, there is the systematic, organized and structured action in recent years to dismantle the fundamental human rights of the Amazon peoples, particularly their rights to land.

The life and territories of the inhabitants of the Amazon and specifically its Indigenous Peoples are severely affected by the economic and development model that is imposed on the Amazon. It is a model that is based on the overexploitation of the region’s natural assets to incorporate them into the productivity and consumption logic of the main economic centers of the world.

The increasingly intense and accelerated exploitation of the Amazon’s forests, water, and land is made possible by stripping people of their ties with the territories, enabling the takeover and control of large companies and economic groups. The actions of the States, which are mainly responsible for the care of the common good, are directed most of the time to facilitate this logic of accumulation and exploitation, with very short-term and colonial views of development, contributing to a situation of permanent violations of fundamental human rights.

Since 1994, some treaties were carried out within the framework of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) that provided the basis for what was later proposed by then Brazil President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC) and which was then set up in 2000 as the Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America (IIRSA). The objective of the IIRSA is to execute the material projects (roads, dams, hydroelectric plants, ports, airports, communications) complementary to the structural adjustment plan according to the Washington Consensus, a package of economic policy recommendations that called for a market-based approach and reduction of state involvement for developing countries, Latin America in particular. These projects were deemed necessary for a new phase of capital accumulation.

The Amazon tends to be seen as “nature,” a “resources reserve,” an “inexhaustible source,” or even a “demographic vacuum” – ideas that end up assumed by the national ruling classes in their relations of subordinate integration or “voluntary servitude.”

The growing importance of China in the world economic scenario opens a new gap in the foreign relations of the countries of the American continent, a gap that was not offered in the world political geography since the end of the Cold War. The business opportunities with Asia, especially China, the main importer of commodities in the world, led to the expansion of capital in the field of agribusiness (soybean, corn, meat, eucalyptus), mining companies and large companies. civil engineering and construction (roads, power stations, ports, etc.), fundamental for the generation of the infrastructure that other sectors needed.

We are thus in a phase of a deep regional, continental and global reconfiguration, with the opening of a new phase of capital accumulation and new alliances. And the major implications of this new megaproject for the Amazon, especially in relation to the scale change they represent, are enormous.

Access to land, water, minerals from the subsoil, oil and gas enter into a dispute between sectors of unequal power. If from the 1960s and 1970s we spoke of an initial phase of megaprojects for the Amazon, now we are facing a megaproject that brings together the structures of several megaprojects.

Extractive and infrastructure megaprojects are part of another form of human adaptation: industrialization. Megaprojects require large amounts of energy, depend on thousands of people for their construction, receive high amounts of financial and technological capital, and transform the forest landscape and hydrological flows where these are located.

In short, the megaprojects transform the adaptation mode to the forest, a change that turns out to be particularly abrupt in rural areas where the traditional forms of adaptation are still valid. In the case of the Amazonian megaprojects, we face extremely rapid processes of industrialization in which rural areas are transformed into urbanized areas within a few years.

In response to this “development” proposal, we note that in general, local peoples are not consulted before the installation of the megaproject on the “industrialization” of their territories and the change in their mode of adaptation. That is why these are forced processes of industrialization of the jungle.

The magnitude of the social and environmental impact generated by this development model is of a qualitatively superior level due to the size and geographic scope of the projects, the number of works carried out simultaneously, and the amount of capital injected into them.

Thus, the Amazon is in a dynamic designed to integrate the subcontinent in the global market through a geographical redesign of great magnitude or spatial expansion. The Amazon therefore takes on particular relevance, not only for the peoples that inhabit the region, but for the entire planet and humanity.

Caring for the Amazon, caring for its Indigenous Peoples and communities

The Pan-Amazonian region encompasses nine countries in an area of seven million sq km, and covers a third of the South American continent.

|

The Amazon is one of the corners of our Common Home (Laudato Si’) where a great and rich cultural diversity coexists. This wealth of human experience includes the nearly 400 Indigenous Peoples – diverse among themselves – that inhabit the Amazon region.

They represent a multiplicity of knowledge and practices, a linguistic plurality, a spiritual richness and dense cosmologies, and a perception of the territory which unites them to their ancestors, to other forms of life, and to the sacred dimension of existence (LS 146).

They mean, in short, the diversity of ways of being, and being in the world and with the world. We start from a recognition of the indispensable contribution that Indigenous Peoples provide in the search for solutions and alternatives to the current socio-environmental crisis that we face in our Common Home.

The challenges of the Amazon and its Indigenous Peoples are huge and daunting and hope is fragile. But there are also signs of life and of great wealth for the whole planet. We see hope from the multiple cultural expressions of Good Living, of Tajimat (an economic inclusion project of the Awajun people through cacao and banana value chains) and abundance, the dense mythical narrative and its cosmologies, their own knowledge, practices, and modes of social organization and land use, the biodiversity kept by these peoples ancestrally, and the community forms of ownership and use of natural assets.

The situation of more than 100 indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation that have references in the Amazon need to be highlighted in a special way. These are peoples that, by their own will or by the pressures of advancing economic borders, opted to control the relationship they want to maintain with their environment and their culture

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alfredo Ferro Medina SJ is the Coordinator of Servicio Jesuita a la Panamazonia (SJPAM) of the Conferencia de Provinciales en América Latina y el Caribe (CPAL). This article is part of the report to the Task Force on Environment and Economic Justice of the Secretariat for Higher Education that met in Rome from 15 to 17 January 2018.

|