|

1. Suggestions for Prayer, Study, and Action

|

Ecological Examination of Conscience

|

1. I give thanks to God for creation and for being wonderfully made. Where did I feel God’s presence in creation today?

2. I ask for the grace to see creation as God does – in all its splendor and suffering. Do I see the beauty of creation and hear the cries of the earth and the poor?

3. I ask for the grace to look closely to see how my life choices impact creation and the poor and vulnerable. What challenges or joys do I experience as I recall my care for creation? How can I turn away from a throwaway culture and instead stand in solidarity with creation and the poor?

4. I ask for the grace of conversion towards ecological justice and reconciliation. Where have I fallen short in caring for creation and my brothers and sisters? How do I ask for a conversion of heart?

5. I ask for the grace to reconcile my relationship with God, creation and humanity, and to stand in solidarity through my actions. How can I repair my relationship with creation and make choices consistent with my desire for reconciliation with creation?

6. I offer a closing prayer for the earth and the vulnerable in our society.

Source: Ignatian Solidarity Network

| |

|

Spiritual Dimension of the Ecological Crisis

LINK TO THE BOOK

|

The Theological and Ecological Vision of

Laudato Si' ~ Everything is Connected

Editor: Vincent J. Miller, Bloomsbury, 2017

This volume provides a comprehensive introduction to the spiritual, moral and practical themes of Pope Francis' encyclical Laudato Si'. Leading theologians, ethicists, scientists and economists provide accessible overviews of the encyclical's major teachings, the science it engages and the policies required to address the climate crisis. Chapters on the encyclical's theological and moral teachings situate them within the Christian tradition and papal teaching. Science and policy chapters, engaging the encyclical and provide introductions to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The book provides a guide for those wishing to explore the issues raised by Laudato Si' but who lack the specialist knowledge required to know where to begin.

| |

|

Support Awakening the Feminine Genius in Humanity

Michelangelo's Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City

NOTE: "Eve" (shown under God's left arm) is integral to the creation of "Adam"

|

|

|

2. Discerning the Signs of the Times in Human Ecology

Beyond ‘No’ and the Limits of ‘Yes’:

A Review of Naomi Klein’s ‘No Is Not Enough’

Robert Jensen

This article was originally published in

Resilience, 20 June 2017

under a Creative Commons License

Naomi Klein understands that President Donald J. Trump is a problem, but he is not the problem.

In her new book, “No Is Not Enough: Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need”, Klein reminds us to pay attention not only to the style in which Trump governs (a multi-ring circus so routinely corrupt and corrosive that anti-democratic practices seem normal) but in whose interests he governs (the wealthy, those he believes to be the rightful winners in the capitalist cage match), while recognizing the historical forces that make his administration possible (decades of market-fundamentalist/neoliberal rejection of the idea of a collective good).

Klein, one of the most prominent and insightful leftist writers in North America for two decades, analyzes how Trump’s “genius” for branding, magnified by his reality TV success, carried him to the White House. But while we may have been shocked by the election of Trump — not just another celebrity but the ultimate “hollow brand” that adds no tangible value to society — she argues that we should not have been surprised:

Trump is not a rupture at all, but rather the culmination — the logical end point — of a great many dangerous stories our culture has been telling for a very long time. That greed is good. That the market rules. That money is what matters in life. That white men are better than the rest. That the natural world is there for us to pillage. That the vulnerable deserve their fate and the one percent deserve their golden towers. That anything public or commonly held is sinister and not worth protecting. That we are surrounded by danger and should only look after our own. That there is no alternative to any of this (pp. 257-258).

Underneath all these pathologies, Klein explains, is “a dominance-based logic that treats so many people, and the earth itself, as disposable” (p. 233), which gives rise to “a system based on limitless taking and extracting, on maximum grabbing” that “treats people and the earth either like resources to be mined to their limits or as garbage to be disposed of far out of sight, whether deep in the ocean or deep in a prison cell” (p. 240).

Klein’s book does not stop with an analysis of the crises, outlining a resistance politics that not only rejects this domination/subordination dynamic but proceeds “with care and consent, rather than extractively and through force” (p. 241). In addition to the “no” to the existing order, there must be a “yes” to other values, which she illustrates with the story behind the 2015 Leap Manifesto (“A Call for a Canada Based on Caring for the Earth and One Another”) that she helped draft.

Klein believes the expansive possibilities of those many yeses are visible in Bernie Sanders’ campaign and others like it around the world. Near the end of the book she lists ideas already on the table: “free college tuition, double the minimum wage, 100 percent renewable energy as quickly as technology allows, demilitarize the police, prisons are no place for young people, refugees are welcome here, war makes us less safe.” She goes on to identify more ambitious programs and policies: “Reparations for slavery and colonialism? A Marshall Plan to fight violence against women? Prison abolition? Democratic worker co-ops as the centerpiece of a green jobs program? An abandonment of ‘growth’ as a measure of progress? Why not?” (p. 263).

Klein is not naïve about what it will take to achieve these goals but stresses the possibilities; “there is reason to believe that many of the relationships being built in these early days [of the Trump administration] will be strong enough to counter the fear that inevitably sets in during a state of emergency” (p. 208).

Recognizing that the 2008 financial crisis created opportunities for more radical change that were lost not only because of the Obama administration’s cautious, centrist approach but because of progressive movements’ timidity, she reminds us that the most important changes in the past (expansions of justice and freedom post-Civil War, during the New Deal, and in the 1960s and ‘70s) “were responses to crises that unfolded in times when people dared to dream big, out loud, in public — explosions of utopian imagination” (p. 217).

Klein is right to challenge the pessimism that so easily sets in when we capitulate to the idea that radical change is politically impossible because of the success of decades of right-wing propaganda and organizing in the United States. Politics is a human enterprise, and therefore humans can change it. Utopian thinking in these realms is to be encouraged, as movements build the capacity to move us toward those goals.

My only critique of Klein’s book — and it is not a minor point — is that while reminding us not to accept artificial, self-imposed limits on social/economic/political fronts, it glosses over the much different status of the biophysical limits we must work within. Klein’s 2014 book on climate change demonstrated how thoroughly she understands what my late friend Jim Koplin called the “multiple, cascading ecological crises” of our time. But what are the implications of facing those crises?

Go back to Klein’s list of programs, which includes “100 percent renewable energy as quickly as technology allows,” alongside such goals as free tuition and a doubled minimum wage. These are very different kinds of projects that shouldn’t be conflated. By building a stronger left/progressive movement, greater equity in higher education and fairer wages could be won. But much more difficult challenges are hidden in “100 percent renewable energy.”

First, and most painful, is the recognition that no combination of renewable resources is going to power the world in which we now live — 7.4 billion people, many living at some level of First World affluence. That doesn’t just mean the end of luxury lifestyles of the rich and famous, nor just the end of middle-class amenities such as routine air conditioning, cheap jet air travel, and fresh fruits and vegetables from the other side of the world. We are going to have to face giving up what we have come to believe we “need” to survive, what Wallace Stegner once termed “things that once possessed could not be done without.” If you have trouble imagining an example, look around at the people poking at their “smart” phones, or walk into a grocery store and survey the endless aisles of food kept “cheap” by fossil-fuel inputs.

If we give up techno-utopian dreams of endless clean energy forever, we face a harsh question: How many people can the Earth support in a sustainable fashion, living at what level of consumption?

There is no magic algorithm to answer that question. Everyone’s response will be a mix of evidence, hunches, and theology (defined not as claims about God but ideas about what it means to be human, to live a good life). I’m not confident that I have an inside track on this, but I’m fairly sure that the answer is “a lot fewer people than there are now, living at much lower levels of consumption.”

There are biophysical limits that we can’t wish away because they are inconvenient, and they limit our social/political/economic options. Those realities include not only global warming but an array of phenomena, all interconnected: accelerating extinction of species and reduction of biodiversity; overexploitation of resources (through logging, hunting, fishing) and agricultural activities (farming, livestock, timber plantations, aquaculture), including the crucial problem of soil erosion; increase in sea levels threatening coastal areas; acidification of the ocean; and amplified, less predictable threats from wildfires, floods, droughts, and heat waves. We are no longer talking about localized environmental degradation but global tipping points we may have already reached and some planetary boundaries that have been breached. The news is bad, getting worse, and getting worse faster than most scientists had predicted.

The goal of traditional left politics — sometimes explicitly, often implicitly — has been to bring more people into the affluence of the First World, with the contemporary green version imagining this will happen magically through solar panels and wind turbines for all. Honest ecological evaluations indicate that in addition to the core left/progressive goal of equity within the human family, we have to think what kind of human presence ecosystems can sustain.

A simple example, but one that is rarely discussed: A national health insurance program that equalizes access to treatment is needed, but what level of high-tech medicine will we be able to provide in a lower-energy world? That question requires a deeper conversation that we have not yet had about what defines a good life and what kinds of life-extending treatment now seen as routine in the First World will not be feasible in the future. Instead of rationing health care by wealth, a decent society should make these difficult decisions collectively, and this kind of ethical rationing will require blunt, honest conversations about limits.

Here’s another example: Increasing the amount of organic food grown on farms using few or no petrochemical inputs is needed, but that style of agriculture will require many to return to a countryside that has been depopulated by industrial agriculture and consumer culture. If we are to increase what Wes Jackson and Wendell Berry call “the eyes-to-acres ratio” — more farmers available to do the work necessary to take better care of the land — how will we collectively make the decisions needed in moving people from cosmopolitan cities, which young people tend to find attractive, to rural communities that may seem less exciting to many?

My point is not that I have answers, but that we have yet to explore these questions in any meaningful depth, and the ecosphere is going to force them on us whether or not we are ready. If we leave such questions to be answered by the mainstream culture — within the existing distributions of wealth and power, based on that logic of domination/subordination — the outcomes will be unjust and inhumane. We need to continue left/progressive organizing in response to contemporary injustices, not only for the short-term progress that can be made to strengthen communities and protect vulnerable people but also to build networks and capacities to face what’s coming.

To ignore the ecological realities that make these questions relevant is not hope but folly; to not incorporate biophysical limits into our organizing is to guarantee failure. Until we can acknowledge the inevitability of this kind of transition — which will be unlike anything we’ve faced in human history — we cannot plan for it. And we cannot acknowledge that it’s coming without a shared commitment not only to hope but grief. What lies ahead — coming in a time frame no one can predict, but coming — will be an unprecedented challenge for humans, and we are not ready.

Saying no to the pathological domination/subordination dynamic at the heart of the dominant culture is the starting point. Then we say yes to the capacity for caring collaboration that we yearn for. But we also must accept that the systems of the larger living world — the physics and chemistry of the ecosphere — set the boundaries within which we say no and yes.

No one can predict when or how this will play out, but at this moment in history the best we can say about the fate of the human species is “maybe.”

We have a chance for some kind of decent human future, if we can face the challenges honestly: How do we hold onto the best of our human nature (that striving for connection) in the face of existing systems that glorify the worst (individual greed and human cruelty)? All that we dream is not possible, but something better than what we have created certainly is within our reach. We should stop fussing about hope, which seduces too many to turn away from difficult realities. Let’s embrace the joy that always exists in the possible, and also embrace the grief in what is not.

We must dare to dream big, and we must face our nightmares.

As I tell my students over and over, reasonable people with shared values can disagree, and friends and allies often disagree with my assessment of the ecological crises. So, let’s start with points of agreement: We must say no not only to Trump and the reactionary politics of the Republican Party, but no to the tepid liberal/centrist politics of the Democratic Party. And we must push the platform of the social democratic campaigns of folks like Sanders toward deeper critiques of capitalism, First-World imperialism, white supremacy, and patriarchy.

But all of that work will be undermined if we cannot recognize that remaking the world based on principles of care is limited by the biophysical realities on the planet, an ecosphere we have desecrated for so long that some options once available to us are gone, desecration that cannot magically be fixed by a technological fundamentalism that only compounds problems with false promises of salvation through gadgets.

No is not enough. But yes is not enough, either. Our fate lies in the joy and grief of maybe.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Robert Jensen is a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin and board member of the Third Coast Activist Resource Center in Austin. He is the author of Plain Radical: Living, Loving, and Learning to Leave the Planet Gracefully and The End of Patriarchy.

|

|

3. Advances in Sustainable Development

Spotlight on SDG5:

Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls

Ben Tritton

Originally published by

Deliver 2030, 10 July 2017

under a Creative Commons License

As a contribution to the 2017 High-Level Political Forum and the thematic review of SDG 5, UN Women produced a number of infographics to highlight the gaps in gender data across the SDG framework, as well as a brief on the need to mainstream disability into efforts to achieve SDG 5.

Target 5.2: Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation

|

What does the data say?

Gender equality and women’s empowerment is integral to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This thematic spotlight on SDG 5 is part of a series showcasing where women and girls stand against select SDG targets and was produced in support of the High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development at UN Headquarters in New York from 10–19 July, 2017.

View the infographics

Making the SDGs count for women and girls with disabilities

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development provides the global community with an enormous opportunity and the moral obligation to work towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for all women and girls, and address the rights and demands of women with disabilities as a matter of priority. In line with several critical areas under thematic review at the High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development in 2017, this brief underlines the need to mainstream disability into all efforts to achieve gender equality and women’s empowerment (SDG 5).

View the brief

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ben Tritton is a Communications Assistant in the Growth, Poverty and Inequality Programme of the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). He was previously a journalist at the BBC News Channel and a local newspaper.

|

4. Advances in Integral Human Development

Tearing Down the Walls that Keep Us

from Finding Common Ground

JoAnn McAllister

Originally published in

Waging Non-Violence, 19 May 2017

under a Creative Commons License

|

The current occupant of the White House wants to build a “real,” “big,” “serious” wall. To avoid a government shutdown, the administration wavered on the timing of funding. But that does not mean a wall, or walls, will not be built. Walls are material structures, and — maybe more importantly — they are metaphors. They promote ideas like possession, property and separation, as well as mine, yours, who belongs, and who doesn’t belong. They create emotional responses: safety, trust, envy, frustration, fear, anger, dread, hostility. The wall on the border between the United States and Mexico is both material and metaphorical. If you have not looked at pictures of the walls, fences, or barriers already installed on some 650 miles of the 2,000-mile border, you should do so right now. Considerable damage to the environment, the economies of border communities, and individual human lives has already been accomplished by the militarization of the border.

In 1961, the Berlin Wall appeared almost overnight. It was physical and metaphorical, carrying a weighty ideological message to Western “fascists,” who, according to the U.S.S.R. were trying to destroy the socialist state. From the West’s perspective, the purpose of the wall was to deny people access to the West and, importantly, to its message of freedom. All walls carry multiple messages depending on your point of view. The wall on the border with Mexico has different meanings depending on which side of the physical and metaphorical wall you are on. Attorney Gen. Jeff Sessions has different ideas about the wall and the people it prevents from entering the United States than do the ranchers and farmers whose land is often divided by a river that does not respect human boundaries.

While construction may be impeded, the idea still exists. It exists as part of an “unconscious system of metaphorical thought,” according to Tom Vanderbilt, in a November New York Times essay about the insidious power of ideas. As a metaphor, the idea of a “wall” is the centerpiece of the new administration’s approach not just to the border, but also to the rest of the world. More barriers along the border could have dire environmental consequences for specific species and the biodiversity of the region. As an environmentalist, I am horrified at this scenario and, yet, I believe that the idea of the wall is as pernicious a consequence of the election as these material impacts.

Everyone is building walls. In Eastern Europe and the Middle East, walls are being built at an exceedingly rapid pace. Vanderbilt cites geographer Elisabeth Vallet’s survey of the 50 actual walls that currently exist, 15 of which were built in the last few years. They are a response to the crisis of immigrant and refugee migration and reflect, as well, the different belief systems — religious and political — that fuel various regional conflicts. A similar surge of nationalist ideology is evident in the United States, too, as “build that wall” became a rallying cry among Donald Trump’s supporters. Those who approve of both kinds of walls exhibit fear and racism. Others believe the myths about job loss or the illusion of physical walls as a solution to a variety of social problems. Nationalism, sometimes labeled populism, has always bubbled under the surface of political discourse in the West, and such rhetoric now has “legs.”

Meanwhile, people who oppose the wall and the immigration policies it represents have also built walls. Articles in Slate, Huffington Post, and elsewhere all carried unforgiving tirades against people who voted for Trump after November 8. This divisive landscape and tendency to build walls represents a crisis for social change activists in engaging a majority of the people to support movements for change.

In the 2001 book “Doing Democracy: The MAP Model of Organizing Social Movements,” veteran social movement activist and trainer Bill Moyer wrote that, “the central task of social movements is to win the hearts, minds and support of the majority of the populace.” After 40-plus years of participating in, planning, training, and analyzing social change and the role of social movements, he stressed the important role of ordinary citizens in successful movements for change. Moyer believed that people would respond to violations of “their deepest values” and that social movements were, in fact, a primary way for people to “challenge unjust social conditions and policies.” As the editor and a co-author of “Doing Democracy,” I too believe that values are at the core of social movements. That is why our political and cultural polarization — that is, the “metaphorical walls” — concerns me and raises questions like: What are these “deepest values?” How do they relate to our “democratic values?” And how many of us share them?

If social movements are to continue to be a “means for ordinary people to act on their deepest values,” as Moyer thought they did, then we need to ask questions about our current culture and the dynamics that are creating more walls than ever before. Are there, in fact, universal values that are widely held today? Numerous authors and many activist groups still cite the Movement Action Plan, or MAP, as a model in understanding the typical stages of social movements on the road to success, the strategies and tactics useful along the way, and the roles that individuals and organizations play in accomplishing movement goals.

Since we completed “Doing Democracy,” I have not encountered any references to the last chapter, titled “Toward the Future.” That chapter encapsulates discussions that Moyer had with many people over the years, and with me during the last several years of his life, about the underlying philosophy of our beliefs and values and knowledge emerging from psychological and sociological research about how we change beliefs and behaviors. Moyer’s analysis of the need for personal and cultural transformation, including the transformation of movement cultures, has not engaged people as much as the “Eight Stages of Social Movements” and “Four Roles of Social Activism” — reflecting, perhaps, an emphasis on strategy and tactics instead of the more personal challenges of being effective change agents by grappling with the philosophical and psychological aspects of social change.

Some will say these considerations sound too individualistic or academic and ask why they are important given the absolutely frightening challenges we face today. In response to this challenge, my colleague Jim Smith and I wrote the forthcoming book “Still Doing Democracy! Finding Common Ground and Acting for the Common Good.” In it, we focus on questions about values, about understanding different beliefs and about how we negotiate the boundaries that different perceptions of the world create so that we can build broader coalitions to support progressive change.

We are once again in an era of large demonstrations that engage the public’s attention. This is good. Some of these events may help groups gain traction in establishing a campaign and building the next movement moment. As longtime organizer and Waging Nonviolence columnist George Lakey has pointed out, protests do not a social movement make. I contend that after the “trigger” events, after the mass demonstrations, and after the first flush of success, such groups will persist in the long struggle to facilitate change only if they are able to engage the “hearts, minds, and support of the majority of the populace.” That is, only if they are able to have a conversation about values and how current conditions violate widely held values. This conversation needs to take place with those with whom you marched, with those who did not march, with those who did not vote (over 42 percent of eligible voters), with those who do not participate in civic life at all, and even with those who voted for the other candidate.

Despite the elation over mass turnouts at recent protests, beginning with the Women’s March, I fear that too little attention is being paid to the more nuanced and disciplined work of listening and learning that’s required to “win the hearts, minds, and support of a majority of the populace.” Unless we are determined to have real conversations — where we are not talking past each other because we are speaking a different language, while using the same words — I believe we will fail.

“Still Doing Democracy!” takes the question of having authentic conversations seriously. Partisans on either side of the progressive/conservative wall use the same language in talking about democratic values. For example, “freedom” is a commonly expressed value that has widely divergent meanings depending on which side of the wall you are on. On one side, being free means to be able to choose to buy or not buy healthcare. On the other side, it means having access to healthcare that you can actually afford to buy. This is not a conversation; there is no common ground here. There is certainly not a shared belief in healthcare as a human right. The belief system and value differences are not only external to the progressive movement world.

Jonathan Matthew Smucker’s analysis of Occupy Wall Street in “Hegemony, How-to: A Roadmap for Radicals,” shows how movement groups create walls that keep them from collaborating with natural allies. I look at the signs at the various marches since January and see a plethora of issues and value statements. But what do these value statements mean? Do people mean the same thing by the words “freedom,” “justice” or “fairness?” Do the people standing next to each other at demonstrations share the vision in “Doing Democracy” of a “civil society in a safe, just and sustainable world?” What kinds of personal and cultural characteristics would describe such a world? These are the questions we need to consider in our groups and in our efforts to engage the “majority of the populace.”

The building blocks of metaphorical walls are the ideas and beliefs that reinforce them. They can be as impenetrable as brick and mortar. Thinking and feeling our way around — through, or over walls — is not always easy, but it is necessary to contribute to real change in a world characterized by diversity of beliefs, perspectives and life experiences.

My approach comes out of a tradition that approaches social problems by asking epistemological questions and analyzes issues through the lens of critical theory. No one needs a degree in philosophy to use these tools — they are everyday skills. Whenever you ask someone where they got a certain idea from, you are asking an epistemological question. What is the source of the information? Is it from the news, their family or the Bible? How firmly do they hold it? Is it an opinion, a belief or, perhaps, “the truth”? As you listen, and this is key, you will learn whether you can have a real conversation. Of course, you must be willing to be similarly transparent, and we must each ask ourselves the same questions. Where do my ideas and beliefs come from? Are they tentative frameworks for making sense of the world, or are they my version of the “truth”?

When you look at social problems through the lens of critical theory you are also asking questions about beliefs. A basic question must be: “Are the people benefitting from this situation, or is some power holder making out like a bandit?” This is the beginning of strategic issue analysis, and it too must include close scrutiny of the stories that substantiate the walls of political belief systems. Our approach brings new insights to the analysis of issues in a social, political and cultural environment that is clearly more complex and fragmented than ever before.

In Lakey’s review of Smucker’s book, he suggests that we have, perhaps, not been bold enough in promoting movement values as the new standard worldview. I suggest that we need to engage in an ongoing conversation about values because we live in a world that has significantly changed since the 1960s, when many of these commitments were first framed as “universal values.” We hope “Still Doing Democracy!” will promote these conversations by helping engaged citizens develop an appreciation of different, disparate, competing or conflicting beliefs and learn how to overcome the barriers they create. We need to add these tools to our list of strategies at every stage and as skills to develop in whatever role we are playing.

We must not build new walls. Instead, we should be echoing an earlier call, “Tear this wall down.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JoAnn McAllister, PhD, was a co-author of Bill Moyer’s Doing Democracy: The MAP Model of Organizing Social Movements. She is the co-author of the forthcoming "Still Doing Democracy! Finding Common Ground and Acting for the Common Good," which will be available this summer, and is the president of the Human Science Institute.

|

5. Advances in Integrated Sustainable Development

Development Beyond the Numbers

Selim Jahan

This article was originally published by

Project Syndicate, May 2017

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

Rights granted by Project Syndicate. Copyright Project Syndicate 2017

It has been said that statistics are people with the tears washed away. This is a message that attendees of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund spring meetings in Washington, DC, should bear in mind as they assess progress on global development.

Despite the impressive gains many countries have made, hundreds of millions of people are still being left behind. To highlight this problem, the United Nations Development Program has made social and economic inclusion a major theme of its 2016 Human Development Report, “Human Development for Everyone.” The report offers an in-depth looks at how countries, with support from their partners, can improve development results for all of their citizens, especially the hardest to reach.

Since the UNDP issued its first report in 1990, we have seen significant improvements made in billions of people’s lives worldwide. Back then, around 35% of humanity lived in extreme poverty. Today, that figure stands at less than 11%. Likewise, the proportion of children dying before their fifth birthday has been halved, partly because an additional two billion people now benefit from better sanitation and wider access to clean drinking water.

We should take pride in these achievements; but we must not rest on our laurels. A sizeable number of people are still missing out on these gains. Worse, they are now in danger of being forgotten – literally so. Sometimes, they are not recorded in official statistics at all. And, even when they are, national averages can paint a distorted picture: an increase in average income, for example, might conceal the deepening poverty of some, as it is offset by large gains for a wealthy few.

One of the most profound demographic shifts in recent years has been the massive expansion of a middle class in the global south. The convergence of global incomes has blurred the line between “rich” and “poor” countries. But, at the same time, inequality within many countries has increased. As a result, poverty – in all forms – is a growing problem in many countries, even as the number of people living in poverty worldwide has declined.

Confronting this challenge will require us to rethink fundamentally what development should look like, which is why the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, unlike the previous Millennium Development Goals, apply to all countries – not just the poorer ones.

After decades of making steady development gains, what can we do differently to help the planet’s most disadvantaged people? As the latest Human Development Report makes clear, there is no simple answer. One reason is that those who are being left behind often face disadvantages on several fronts. They are not just short of money; often, they are also sick, uneducated, and disenfranchised.

The problems that affect the world’s most disadvantaged people begin at birth, and worsen during their lifetime. As opportunities to break the cycle are missed, these disadvantages are passed on to subsequent generations, reinforcing their impact.

Still, while today’s development challenges are numerous and complex, they also share common characteristics. Many of the disadvantaged belong to specific demographic groups that tend to fare worse than others in all countries, not least because they face similar economic, legal, political, and cultural barriers.

For example, indigenous peoples constitute just 5% of the global population, but account for 15% of the world’s poor. And, to participate in work and community life, people with disabilities must overcome obstacles that the rest of us often do not even notice. Last but not least, women and girls almost everywhere continue to be underrepresented in leadership and decision-making circles, and they often work more hours for less money than their male counterparts.

Although development policies will continue to focus on tangible outcomes – such as more hospitals, more children in school, and better sanitation – human development must not be reduced only to that which is quantifiable. It is time to pay more attention to the less palpable features of progress, which, while difficult to measure, are not hard to take a measure of.

All people deserve to have a voice in the decisions that affect their lives; but the most marginalized in society are too often denied a say of any kind. Ensuring that those most in need are not forgotten – and that they have the freedom to make their own choices – is just as important as delivering concrete development outcomes.

History has shown us that many of today’s challenges can be overcome in the years ahead. The world has the resources and the knowhow to improve the lives of all people. We just need to empower people to use their own knowledge to shape their futures. If we do that, more inclusive development will be within our reach.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Selim Jahan is Director of the United Nations Human Development Report Office and lead author of the Human Development Report.

|

6. Sustainability Games, Databases, and Knowledgebases

Global Push for Earth Observations Continues

Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GEOSS)

This press release was originally published in

GEO Group on Earth Observations, 13 April 2017

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

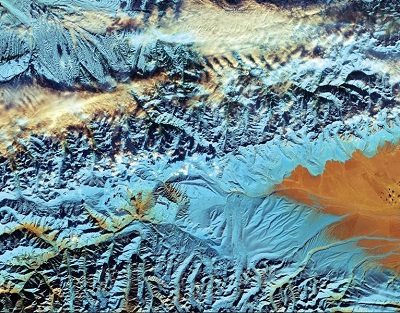

China's Tian Shan Mountains

Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2016),

processed by the European Space Agency (ESA)

The Group on Earth Observations (GEO) has been working for more than a decade to open access to Earth observation data and information, and increase awareness around their socioeconomic value. As GEO moves into the second decade four new global partners are announced to help support GEO’s vision.

The GEO community has been building a Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GEOSS) that links Earth observation resources worldwide across multiple Societal Benefit Areas (SBAs). These SBAs range from Biodiversity and Ecosystem Sustainability, Disaster Resilience, Energy and Mineral Resources Management, Food Security, Infrastructure and Transportation Management to Public Health Surveillance, Sustainable Urban Development and Water Resources Management. The SBAs serve as lenses through which the Member governments and Participating Organizations (POs) that constitute GEO may focus their contributions to GEOSS, with a goal to make the open EO data resources available for informed decision-making.

The four organizations include Conservation International (CI), Earthmind, Global Open Data for Agriculture and Nutrition (GODAN) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Each organization has now joined GEO as a Participating Organization, taking the total number to 110 working internationally to advocate, engage and deliver on open EO data.

“CI empowers societies across the globe to sustainably care for nature through science and partnerships. We are excited to join the GEO community, which has long recognized the power of collaboration in leveraging earth observation to benefit humanity.” Said Daniel Juhn, Senior Director, Integrated Assessment and Planning Program at Conservation International. “Though we face obstacles to achieve the SDGs, we are at a critical juncture where the science of valuing ecosystems, and understanding the full services nature provides to people expands our knowledge and options. We hope this partnership exemplifies bringing together that science, the right policies, necessary collaboration, and advanced technologies to generate the solutions we need to tackle global sustainability challenges.”

“Earthmind supports positive efforts by private, public and non-profit stakeholders to conserve and responsibly manage nature. As one of our main programmes is to recognise conservation in the areas where people live and work, we are most honoured and indeed excited to join the GEO community. In so doing, we hope to further encourage voluntary efforts to observe how we managing our planet in order to take better care for it.” said Francis Vorhies, Founder and Executive Director of Earthmind.

“GEO, its Members and the broad new set of tools provided by geodata constitute a fantastic step forward in the quest to help farmers from all corners of the world improve their yields and Governments to improve their policies to further stimulate agriculture in their respective countries. This is why GODAN is very glad to become part of GEO and to count the GEO partnership among the GODAN network. We believe that this collaboration will be most fruitful for all parties involved” said André Laperrière, Executive Director of the GODAN Secretariat.

"UNICEF has learned through experience that problems that go unmeasured often go unsolved,” said Toby Wicks, Data Strategist at UNICEF. “We will work with the GEO community to link the needs of the world's most vulnerable populations to a rapidly expanding set of data informed solutions, including GEOSS. This partnership signals an effort to build a world in which a near real-time understanding of risks and global challenges, particularly water resources management and disaster resilience, allows us to work harder and faster, for children."

The key engagement priorities for GEO in the coming years involve using open Earth observations to respond to a number of global policy issues. The priorities are tied to the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. These new partnerships will complement existing ones and also help deliver in line with the GEO engagement priorities.

The Group on Earth Observations (GEO)

GEO is a partnership of governments and organizations creating a future wherein decisions and actions for the benefit of humankind are informed by coordinated, comprehensive and sustained Earth observations. GEO Member governments include 104 nations and the European Commission, and 110 Participating Organizations comprised of international bodies making use of or with a mandate in Earth observations. GEO’s primary focus is to develop a Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GEOSS) to enhance the ability of end-users to discover and access Earth observation data and convert it to useable and useful information. GEO is headquartered in Switzerland.

For English-language media enquiries, please contact:

Katherine Anderson – Communications Manager, Group on Earth Observations

Tel: +41 22 730 8429; Email: kanderson@geosec.org

|

7. Sustainable Development Measures and Indicators

Making the Sustainable Development Goals

Consistent with Sustainability

Global Footprint Network

This article was originally published in

Global Footprint Network, 1 September 2017

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

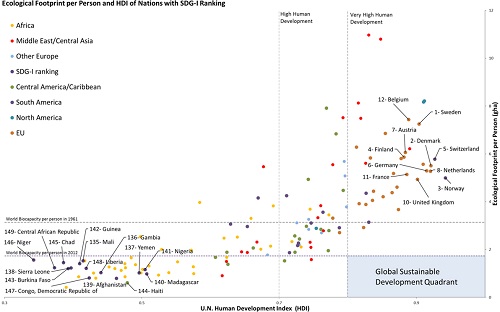

This month, the UN General Assembly (UNGA 72) will convene in New York City for its 72nd Regular Session. The summit’s theme is “Focusing on People: Striving for Peace and a Decent Life for All on a Sustainable Planet.” The phrase closely echoes Global Footprint Network’s vision “that all people can live thrive within the means of our planet.” Which prompts us to raise the question, why won’t the significance of resource security, planetary boundaries, environmental resilience, or any of these themes be included in the topics of discussion at UNGA 72? This blind spot is nothing new. In a recent article published by Frontiers in Energy Research, Global Footprint Network highlighted how the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted two years ago this month are vastly underemphasizing sustainability. The authors of “Making the Sustainable Development Goals Consistent with Sustainability””—Footprint Network CEO and Co-founder Mathis Wackernagel, Program Director Laurel Hanscom, and Director of Research David Lin—found that countries scoring high on a recently developed SDG index also had, without exception, high Ecological Footprints per person. Using the Bertelsmann and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN)’s SDG index to quantify SDGs, the article reveals that the sustainable development goals are largely (short-term) development goals, vastly underperforming on sustainability. Global Footprint Network and the authors of the paper are strongly in favor of the SDGs. The trio explains this contradiction by highlighting the SDG index rankings within a sustainable development framework that uses the Ecological Footprint and UN Human Development Index (HDI). The Footprint-HDI framework describes necessary outcomes for sustainability and well-being: to have high human development (as measured by HDI) within a resource demand that fits on this planet (as measured by an Ecological Footprint per person that is smaller than the world average biocapacity of 1.7 global hectares per person). What becomes evident is that higher performance on the SDG index correlates acros the board with high Ecological Footprints. “The Ecological Footprint of the index’s top 20 ranking countries is so large that if all other countries consumed at the same rate, it would take the ecological capacity of over three planet Earths to materially support all of humanity,” they write. “This level of demand on the planet is clearly not sustainable.”

CLICK ON THE CHART TO ENLARGE

Ecological Footprint per person and HDI by country indicate how closely each country is to basic global sustainable development criteria (high human development, within resource requirements that are globally replicable). Each number indicates the country’s ranking on the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) index (only top and bottom 10 are marked here). It shows that SDG performance closely follows a conventional rather than a sustainable development path.

The conclusions in the paper make sense if we consider that countries who are the most economically well off have achieved economic well-being through traditional economic means involving exploitation of natural resources and carbon-intense industrialization. Post industrialization, the now high-income countries are in the strongest position to implement and achieve the targets set by the SDGs. Most importantly, the paper points out that the SDGs need to increase their focus on resource security and environmental resilience in order to deliver lasting results. After all, sustainability is a prerequisite for well-being. Wackernagel, Hanscom, and Lin conclude that the SDGs need to more robustly embrace the reality of resource constraints and climate change. The near-exclusion of resource security aspects makes the current SDGs fall short of actively advancing human wellbeing without further depleting the very natural capital on which human wellbeing and development depends, they write. The SDGs are aimed at creating a pathway towards a sustainable future. Therefore, the SDG initiative is imminently important and needs to be strengthened as humanity’s future depends on it. However, it has to be consistent with the outcome of thriving lives for all within the means of the planet, as Wackernagel explained in a TEDx talk on measuring sustainable development outcomes. Wackernagel, Hanscom, and Lin conclude in their recent article: “Ignoring physical constraints imposed by planetary limits is anti-poor because with fewer resources to go around, the lowest-income people will lack the financial means to shield themselves from resource constraints, whether it is food-price shocks, weather calamities, or energy and water shortages. All the legitimate and important development gains the SDGs seek to achieve will fall tragically short without the natural capital to power the economy of each nation, region, city, or village. If we want to have a future, the SDGs need to robustly embrace the reality of resource constraints and climate change. Also, we need robust accounting tools that track the outcomes. Without such rigorous metrics, there is great risk to misallocate development investments.” Additional ResourcesFull article “Making the Sustainable Development Goals Consistent with Sustainability” TEDx talk on measuring sustainable development by Mathis Wackernagel, CEO of Global Footprint Network Brief introduction to measuring sustainable development outcome

|

8. Sustainable Development Modeling and Simulation

Modeling Sustainability:

Population, Inequality, Consumption, and

Bidirectional Coupling of the Earth and Human Systems

Safa Motesharrei et al

This article was originally published in

Oxford Journals National Science Review, 11 December 2016

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

Abstract

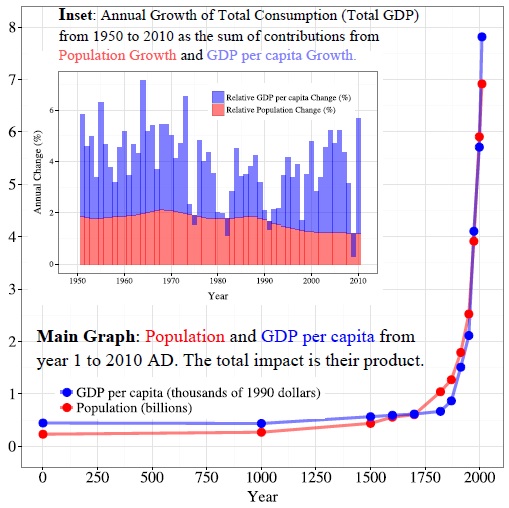

Over the last two centuries, the impact of the Human System has grown dramatically, becoming strongly dominant within the Earth System in many different ways. Consumption, inequality, and population have increased extremely fast, especially since about 1950, threatening to overwhelm the many critical functions and ecosystems of the Earth System. Changes in the Earth System, in turn, have important feedback effects on the Human System, with costly and potentially serious consequences. However, current models do not incorporate these critical feedbacks. We argue that in order to understand the dynamics of either system, Earth System Models must be coupled with Human System Models through bidirectional couplings representing the positive, negative, and delayed feedbacks that exist in the real systems. In particular, key Human System variables, such as demographics, inequality, economic growth, and migration, are not coupled with the Earth System but are instead driven by exogenous estimates, such as UN population projections. This makes current models likely to miss important feedbacks in the real Earth-Human system, especially those that may result in unexpected or counterintuitive outcomes, and thus requiring different policy interventions from current models. The importance and imminence of sustainability challenges, the dominant role of the Human System in the Earth System, and the essential roles the Earth System plays for the Human System, all call for collaboration of natural scientists, social scientists, and engineers in multidisciplinary research and modeling to develop coupled Earth-Human system models for devising effective science-based policies and measures to benefit current and future generations.

DOWNLOAD THE COMPLETE ARTICLE

|

|

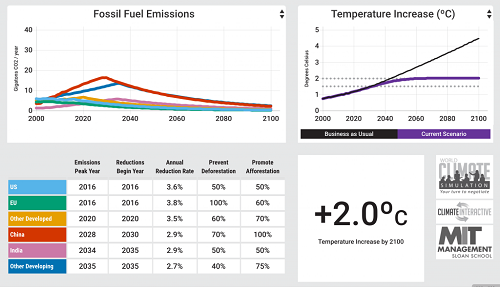

"C-ROADS is an award-winning computer simulation that helps people understand the long-term climate impacts of policy scenarios to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It allows for the rapid summation of national greenhouse gas reduction pledges in order to show the long-term impact on our climate." For more information, click

here.

|

9. Fostering Sustainability in the International Community

How to Halve Poverty In All Its Dimensions by 2030

Yekaterina Chzhen and Lucia Ferrone

This article was originally published in

Deliver 2030, 18 October 2017

under a Creative Commons License

The way countries define poverty is going to matter for their probability of achieving Sustainable Development Goal 1, Target 1.2. It calls for reducing at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions by 2030. This means that national governments can establish the standards against which they will be measuring progress in just over a decade.

For example, if we measure multidimensional poverty in a way that the starting rate is too high, we will struggle to halve it. Define it at too low a level, and further progress may be harder to achieve. Try to game Target 1.2 by fudging your dimensions and you betray the spirit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). So how can governments define multidimensional poverty in a way that halving the poverty rate will be realistic and amenable to policy intervention, while representing a true improvement in people’s well-being?

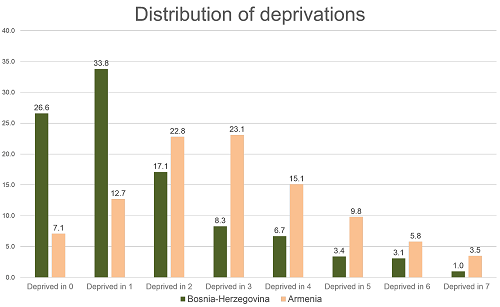

In a recent paper we simulate different scenarios for lowering multidimensional child poverty in two small middle-income post-socialist European countries: Armenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). Their UNICEF offices carried out child poverty studies using data from household budget surveys collected in 2011-2013. UNICEF chose the dimensions of child poverty in consultation with government and civil society counterparts to reflect national standards and priorities.

Each study used seven dimensions of poverty from this list: clothing, education or educational resources, housing, information access, leisure, nutrition, social participation or social relations, and utilities. UNICEF had initiated these studies before the SDGs have been adopted, so no one worried about halving the resulting poverty rate by 2030 when they were coming up with a definition of poverty. The rate of multidimensional child poverty was twice as high in Armenia as in BiH: four in five (80%) versus two in five (40%) school-age children, respectively, were deprived in two or more out of seven dimensions.

CLICK TO VIEW LARGE CHART

There were differences between the two countries in the intensity of multidimensional child poverty and way various dimensions interacted with each other. In BiH, one dimension influenced child poverty disproportionately (i.e. information access) and was not highly correlated with other dimensions. In contrast, no single dimension dominated in Armenia, and the majority of children deprived in two or more were deprived in four dimensions (i.e. leisure, housing, social relations, and utilities).

To understand the mechanics of reducing multidimensional child poverty, we simulated several scenarios of lowering deprivation in different dimensions at a time. We played around with switching the deprivation status from 1 “deprived” to 0 “non-deprived” for a random selection of children in the dataset for different combinations of deprivations. For example, if all school-age children in BiH had a networked computer at home (i.e. no deprivation in information access), the multidimensional poverty rate would go down by more than one-third (35%). This goes a long way towards halving poverty to reach the Target 1.2.

An alternative, but similarly effective strategy for BiH, would be to eliminate the correlation between the two dimensions that have the highest deprivation count (i.e. information access and leisure), while maintaining the proportion of children deprived in each of them. As long as it is no longer the same children who are deprived in both of these dimensions, but some deprived in one and others in the other, the overall multidimensional poverty headcount would also fall by over one-third (35%).

However, these strategies would not work in Armenia, where the majority of school-age children are deprived in two out of four dimensions at once and no single dimension stands out. Of the four scenarios we considered, the best we could do would be to lower the poverty rate by just over one-quarter (28%) by halving the deprivation rates in three dimensions and reducing it by one-tenth in the other four.

We also simulated the effects of giving different amounts cash to the households where multidimensionally poor children live. We did this by modelling the associations between household consumption and children’s deprivations in different dimensions. Cash transfers to the poor can be a powerful tool for improving children’s outcomes in nutrition, health and education, to name just a few (see https://transfer.cpc.unc.edu/).

Some deprivations (e.g. nutrition and clothing) are more sensitive to household consumption, so cash transfers would be more effective in tackling them. Others (e.g. utilities) depend more on the local services infrastructure. Our simulations suggest that in a country like BiH, giving all consumption-poor households with children enough money to lift them out of monetary poverty would also eliminate multidimensional child poverty. In a country like Armenia, where children tend to be deprived in a greater number of dimensions simultaneously, even such an expensive strategy would not make a sizeable dent in multidimensional child poverty.

We learned from our analysis that a country’s potential to halve multidimensional child poverty by 2030 hinges on the definition of the poverty measure they adopt in the first place. It influences both the “baseline” rate of poverty against which progress will be measured and the policy levers to achieve the goal. An effective strategy is likely to involve a multi-sectoral approach with cash transfers, information provision and investment in public services and infrastructure.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Yekaterina Chzhen joined the UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti in 2013 after two and a half years as a Post-Doctoral Fellow in Quantitative Methods in Social and Political Sciences at the University of Oxford (Nuffield College). She has completed her PhD in Social Policy & Economics at the University of York in 2010. She has 12 years of experience in applied quantitative social science research at universities and international organisations. Her main research interests are in the areas of comparative social policy, multidimensional poverty, and child well-being. Kat is currently working on: Innocenti Report Card series, Multiple Overlapping Deprivation Analysis (MODA), and issues in children's time allocation in development settings.

Lucia Ferrone joined the Office of Research in November 2014, to work on Multidimensional Overlapping Deprivation Analysis (MODA) and child poverty, both in low and middle-income countries. She holds a Ph.D. in Development Economics, and her research interests lie in family and population economics, child well-being, and migration; she is also particularly interested in longitudinal analysis. She is a geek and a feminist, not necessarily in this order.

|

|