Colorado author Benjamin Dancer wrote a “a hard-shooting kick of a thriller” to raise awareness about the rapid growth of the human population. “Disguising a heart of pure poetry,” the novel Patriarch Run has been described as “a literary meditation clutching a straight razor behind its back.”

That straight razor is the truth. “It is my intention,” said Benjamin, “to use the platform of my thriller to promote real-world solutions to overpopulation.”

Population Media Center, an international leader in entertainment-education, knows that for media outreach to be effective, a story must be a thrill for the audience —otherwise, it won’t work. That’s the approach Benjamin took with Patriarch Run. The story is “bold, beautifully written, and surprising page-by-page.”

Benjamin’s eco-thriller is “a gripping exploration of our gendered culture and the poignant moments entailed in coming of age.” It has been endorsed by a number of leaders in the sustainability movement, including Paul Ehrlich, Bill Ryerson, and Alan Weisman. You can read those endorsements and learn more about Patriarch Run at Benjamin’s website.

How do you leverage an “unsparing” thriller to raise awareness about the most important issue of our time? Benjamin answers that question with an impressive list of outreach activities:

- Population Media Center and Benjamin will be engaged in a media tour in which he will use the platform of his book to direct attention to sustainability issues, namely the unintended effects of population growth.

- Benjamin is also partnering with journalist Alan Weisman and filmmaker Dave Gardner of GrowthBusters in the first episode of a webinar series about the human population.

- Benjamin and the Center for Biological Diversity are distributing endangered species condoms at his events.

- Journalist Tedd Koppel’s recent book Lights Out has opened the door for Benjamin to connect the issue of population growth to national security by revealing just how vulnerable America is. The bad guy in Patriarch Run intends to cripple the country by taking down the power grid. A threat that had no teeth until the country’s growing population outstripped the land’s “pre-electrical” carrying capacity. Prominent national security experts have endorsed Patriarch Run’s realistic portrayal of this threat.

- Ethicist Travis Rieder, recently profiled on NPR, and Benjamin will be discussing the ethics of population based on Jack’s world view. Jack is a character in Patriarch Run.

- Benjamin is also directing readers to a rich set of resources about these issues in the Discussion Guide at his website.

“There is no more important issue for us to tackle than population growth,” Benjamin said. “Almost every other global concern stems from this root cause. Patriarch Run is meticulously researched and realistic. I wrote it to sell; my calculation was that the better the story does in the marketplace, the larger the platform I will have to bring attention to this problem.”

About Patriarch Run

Nine years ago, Jack Erikson was deployed to China to protect the United States from a cyberattack. Now, suffering from a drug-induced amnesia, he is unable to recognize his own son. What Jack knows for sure is that an elite group of operators is determined to kill him. What he does not yet remember is that he controls a cyber-weapon powerful enough to return human civilization to the Stone Age. If Jack lives long enough to piece together his mission and his identity, he will be forced to choose between the fate of humankind and that of his own family.

Readers of Cormac McCarthy and Peter Heller will appreciate both the suspense and the Western setting. In his thrilling literary debut, Benjamin Dancer also explores the timeless themes of fatherhood, sustainability and the fraying fabric of global stability. Learn more here!

|

ABOUT MAHB

The Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere (MAHB) connects activists, scientists, humanists and civil society to foster global change. It's mission is to:

- Foster, fuel and inspire a global dialogue on the interconnectedness of activities causing environmental degradation and social inequity and the threat of collapse;

- Create and implement strategies for shifting human cultures and institutions towards sustainable practices and an equitable and satisfying future.

|

Readers of my eco-thriller Patriarch Run tend to struggle with the character Jack. It’s hard to know what to make of him. Is he the good guy or the bad guy? Intelligent people can disagree on the answer to that question.

I wrote the novel, as I am writing this post, as a bit of a thought experiment: a piece to provide some conversation about the strong feelings Jack evokes. That being said, beware: there are plenty of spoilers below.

Because Jack is motivated by the unintended consequences of continued population growth, let’s start the conversation there.

Any population that is growing will eventually double. That is a mathematical fact. Even with a growth rate as low as the current growth rate of the human population, around 1%, it only takes 70 years to double, which is about one human lifetime. Moreover, a population that perpetually grows will eventually become too large to be sustainable. I think we can all agree on that without deciding on a precise number for an ecological tipping point.

A supposition that might be more controversial, though it shouldn’t be, is that the vast majority of the global concerns that vex you and me (concerns such as Climate Change, declining liberty, hunger, national security, the rapid extinction rate of other species, environmental degradation, mass human migration, economic challenges, etc.) are all unintended consequences of continued population growth. Notice, by the way, that the problems cited above span the political spectrum. That’s because the unintended consequences of continued population growth are bipartisan in their scope.

Back to the story. Jack made a calculus in my eco-thriller regarding the fate of the human species. He examined what he knew of our innate biological and psychological drives and calculated that the probability of our species voluntarily reducing its own growth rate to zero (or less) was lower than the probability of zero growth being forced upon our species. In other words, he calculated that left to our own devices, we’d likely run our species off an ecological cliff.

If we do nothing and wait until nature puts the brakes on our population, according to Jack’s way of thinking, those brakes will take the ugly form of an overpopulation-induced apocalypse, resulting in billions and billions of deaths.

Thus far Jack’s logic works as follows: people aren’t going to fix overpopulation; nature’s fix will result in an unacceptable number of deaths; therefore, the moral thing to do is to choose the lesser of two evils and precipitate a super-genocide. In other words, according to Jack’s morality, murdering about 7 billion people (including me and, unfortunately, you, along with all the people we dearly love) is a better alternative than allowing many more people to die, at some point in the future, when the human population would be much larger. That future population might be as massive as 10, 24 or 30 billion people, depending on what the actual limit of the human population might be before it triggers its own collapse. As an aside, the population was about 6.884 billion in 2010, the time of the narrative, and Jack probably assumed a few million of us would survive in the world he created.

For the sake of brevity, I won’t say much here about Jack’s chosen mechanism of destruction, except for that it is (unfortunately for you and me and everyone we love) a realistic threat. As a matter of fact, many prominent national security experts have endorsed the realism of Patriarch Run’s depiction of that threat. So let’s all be thankful that Jack is only a thought experiment. I wouldn’t want him walking among us.

Apart from Jack’s obsession with mass murder on a scale never seen before in human history (and a unique skill set that actually makes him capable of pulling it off), he’s a pretty likable guy. So readers really struggle with the question: is Jack the good guy or the bad guy?

The moral calculus presented here might remind the reader of a classic ethical dilemma known as the trolley problem. Sarah Bakewell described the problem in the New York Times like this:

|

You are walking near a trolley-car track when you notice five people tied to it in a row. The next instant, you see a trolley hurtling toward them, out of control. A signal lever is within your reach; if you pull it, you can divert the runaway trolley down a side track, saving the five — but killing another person, who is tied to that spur.

|

Basic Trolley Scenario by John Holbo | Flickr | CC BY-NC 2.0

|

Which is the correct choice? In surveys, most people, 90%, opt to pull the lever, choosing one death instead of five. In other words, 90% of us calculate the morality of the situation like Jack.

To make the question more interesting philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson presented The Fat Man version:

|

As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track toward five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by dropping a heavy weight in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you–your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

|

Bridge Situation by John Holbo | Flickr | CC BY-NC 2.0

|

Although most people are willing to pull the lever in survey questions, very few can see themselves pushing the man. The number of lives at stake are the same in both scenarios, so why do people feel more comfortable pulling the lever than pushing the man?

Jack is clearly in the minority now. He would have pushed.

This thought experiment is a useful tool in examining our morality. Ethicists tend to boil the dilemma down to this: we can act on a rational and utilitarian calculus, intentionally killing one to save five; or we can respect the subrational instinct that makes us recoil at the thought of pushing a man to his death, choosing not to act, thus allowing the avoidable death of the five.

Patriarch Run can be viewed as a fleshed out version of the trolley problem. The story assumes a scenario in which the exponential growth of the human population threatens the extinction of the species. One man, Jack Erikson, has an opportunity to stop the unfolding ecological crisis, but to do so he must sacrifice even his own family. Depending on how you choose to solve the trolley problem, Jack is either the villain or the protagonist of the narrative.

I’d be really curious to know how you answer, or perhaps even reframe, the question, as all this makes for interesting conversation.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Benjamin Dancer is the author of the literary thriller Patriarch Run, the first book in a series that will include Fidelity and The Story of the Boy. He also writes about parenting, education, sustainability and national security. He is the Director of Public Relations for the Colorado EMP Task Force On National and Homeland Security, which is the Colorado branch of a Congressional Advisory Board. Benjamin also works as an Advisor at a Colorado high school where he has made a career out of mentoring young people as they come of age. His work with adolescents has informed his stories, which are typically themed around fatherhood and coming-of-age. You can learn more about Benjamin at BenjaminDancer.com.

|

A vision from the field:

Climate challenges in developing countries

Pedro Walpole, SJ

This article was originally published in

EcoJesuit, 15 October 2016

under a Creative Commons License

I talk of things seen at present and of what societies in Asia Pacific are seeking and speak of four areas of change, all interconnected. The objective is to identify key challenges and contribute to strengthening relations and systems by focusing on experiences and lessons learned.

How is the world of climate change seen ‘in the field’ and what are we called to bridge? Recently a friend relayed local events where a rural woman killed her four children and then committed suicide. A week later, her husband killed himself. This is a very sad story of a very poor family in despair.

How can the poor secure daily needs and at the same time be helped to sustain the natural resources around them? How can we have full cycle production and lifestyles that care to include others without waste? That would truly be good news!

Four areas of change and challenge

1. Climate change and resilience that challenge us to reduce vulnerability and to increase adaptation measures that change the status quo

Typhoon Haiyan was a near perfect storm riding across the Pacific Ocean for six days in November 2013 on course for Tacloban City, Philippines. The scientific measurements and social realities of vulnerability and infrastructure were all known before the event. We knew what was coming but not how to act. We need to break the cycle of vulnerability.

Knowledge is not action. Science and technology do not impact without personal, political, and economic commitment. Science can more actively support societal transformations by engaging elements of society in their concerns. Defining hazards, responsibilities, and protocol is critical in addressing the vulnerabilities to climate change and having effective community evacuation strategies.

The precautionary principle should now be a norm in addressing environmental concerns. Scientific certainty should prevail as a point and time for comprehensive action.

As with relief and building back better in Banda Aceh, the assessment in the Philippines reveals the need to learn a new form of governance in times of crisis. The challenges on the ground of communication and social learning, governance and solidarity are evident.

There were 10 lessons learned from these painful experiences:

- Social vulnerability where the poor are exposed to hazards at some point results in disaster.

- Understanding of the range of disaster risks is essential for better planning and response.

- Adaptation of necessity must occur without first needing to be convinced by local experience of disaster.

- Safe infrastructure and social preparedness must enable and empower local communities.

- Strengthened local capacities and broader participation in governance lead to reduced risks and greater human security.

- Effective emergency governance by government and other agencies – one-stop- shop with standards and accountability is desired, not the status quo of “ordinary time” government bureaucracy.

- It is essential that redesign of relief continues to build better and more sustainable communities that are environmentally sustainable and socially and economically inclusive if future disaster is to be reduced.

- National prioritization of problem-focused science and its communication are needed.

- Social and economic inclusion is critical in reducing risk and creating resilience.

- Resilience means livelihood where people can live under better economic conditions and so reduce their vulnerability and build community relationships.

Even with these lessons, switching to low carbon national economies and lifestyles is urgent. A carbon lifestyle makes our Asian urban centers barely inhabitable. Beijing’s city government last December issued a “red alert” and schools and construction sites closed, traffic was restricted. Air pollution reached 500µ/m3 and in other cities this doubled and even trebled, prompting the government to respond and implement new policies.

The kind of science we need is a science where people matter. Science is not simply a problem of knowledge but of identifying society’s problems and setting these as priorities of investigation and communication. Great commitment is needed in doing sustainability science as engaging society in problem-solving requires much adjustment from all sectors to trust and work together.

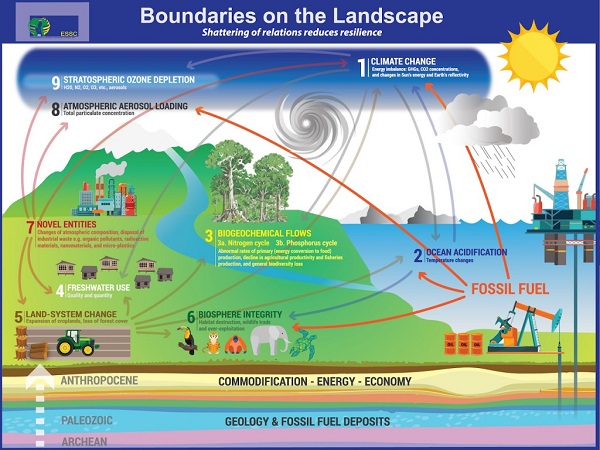

The planet’s boundaries when put on the landscape are easier for people to see where they connect and can make a contribution. Climate change, air pollution and ocean acidification are all due to the use of fossil fuels. The use of fossil fuels is not a planetary boundary but a boundary of the global economy as presently designed. Photo credit: Environmental Science for Social Change (ESSC), Philippines

|

2.Land use change and relations in the landscape that challenge us to increase forest cover, reduce chemical use in commercial agriculture, and improve water

The planet’s boundaries when put on the landscape are easier for people to see where they connect and can make a contribution. Climate change, air pollution and ocean acidification are all due to the use of fossil fuels. The use of fossil fuels is not a planetary boundary but a boundary of the global economy as presently designed.

Other driving forces are land use change and novel entities, many of which add to the threats to agriculture and biodiversity. These three key boundaries affect the stability of all other boundaries and also the marginality and migration of the poor.

We have seen forest loss in every country in Asia, with the expansion of oil palm plantations as recent drivers. For Indonesia, both the loss of such carbon sinks and release of carbon to the atmosphere are of global concern. The country’s Constitutional Court recently annulled the government’s ownership of customary forest areas and ruled that: “members of customary societies have the right to … use the land to fulfill their personal and family needs.”

Policies and strengthening of the legal framework are essential in addressing national ownership of the problems and control of international corporate abuse. Another example is the legal action taken in China over toxic liquids dumped in the Tengger desert, an oil spill in Bohai Bay and emission violations of imported vehicles. A new environmental law of 2015, now allows for public interest litigation.

3. Food security and resource needs that challenge us to ensure that production and distribution of food is socially equitable, in accordance with people’s needs

Social development has not kept pace with the rapid economic growth, and there are “two faces of Asia – one of progress and prosperity, the other of continued poverty.” (ADB 2013) Rising incomes and affluence continue to drive greater demand for more protein-rich food, with enormous implications in food production. Rising prices especially rice and wheat affect food sovereignty with greatest impact on the poor who allocate 50-70% of their budget to food. With 60% of population relying on local agriculture, climate change is a major challenge to food security.

Current food production and distribution systems are failing to feed the world. Agriculture produces enough for 12-14 billion people, enough even for the projected 2050 population and still, one in eight of the world’s population are chronically hungry. The cause of hunger is not lack of food, but lack of access and the inability to buy.

With increasing urbanization as in China, maintaining food security will be an accompanying priority in the region as arable land becomes scarce, apart from rehabilitating heavily contaminated land and restoring aquifers. Farmers are also aging (in the Philippines, the average age of a farmer is 57) and rural youth are increasingly uninterested, not least because of the hard labor involved and the risks resulting in insecurity.

4. Culture, livelihood and integrity that challenge us to find a sense of belonging in each culture and country, while livelihood ensures a quality of life and giving reason to live

China has adopted forestry-based programs to improve environmental conditions and reduce rural poverty, with relative success in increasing forest cover and rural household income. The experiences of communities in the counties of Ningshan, Anhua, and Ledu illustrate the impact of collective forest tenure reform, in improving income and employment while ensuring levels of environmental protection.

In the modern age of medicine, it is hard to understand the figures of 65-80% of the global population relying on medicines derived from forests as their primary health care. Yet the Yao people living across the mountains of south and southwestern China, or Dzao in the mountains of Vietnam, Laos, Thailand and Myanmar are one of the foundations of Chinese medicine today.

Cultures are living relations, not simply preserved ways of the past and so there is a need to adapt. Some of the Pulangiyen youth who live on the land of their ancestors in Mindanao, Philippines are making a new path. The youth like motorbikes, cellphones, computers and the modern world. Yet they also spend their time growing trees on the steeper slopes protecting the spring water sources of the community.

Indigenous peoples need not simply be laborers on their ancestors’ land but dignified communities contributing to the richness and sustainability of society. The role of such communities in forest management needs to be integral to their practices and can be shared more widely if their contribution to ecological services is respected. These communities are not merely tourist destinations and living museums but critical learning experiences for our urban and academic communities.

Nurturing a community of practice for reconciling with creation helps us more effectively network for justice. If we collaborate the impact of our actions broaden and we gain more understanding, and even though they maybe small actions, they connect with the global. Learnings are greater when we participate in joint action.

Summary

With more than half of the planet’s population and capacity in the region, many of the most vulnerable populations of the poor are rural. While they hold a certain flexibility to subsist, they cannot be stretched anymore and the environments where they live are again most vulnerable. Similarly for urban poor populations, the social and economic inclusion is urgent. I have four main points that partly summarize:

1. What’s the vision?

Looking for a greater connectivity, governments are becoming more aware of their responsibility for the condition of the vast majority of their people who are poor and this is impinging on national level discussions of economic growth, knowing that the trickle-down does not work. Some rural focused actions that might be crucial are:

a) provision of credit and insurance and inclusion of farmers in more resourceful management of environmental concerns

b) regeneration of forests, soils and water resources, control of chemicals in commercial agriculture, and regulation of animal feeds

c) youth education focused on leadership in service and education on the social and environmental roles of people.

2. Scenario planning and ‘what if’

We need a language in government not of crisis or denial, but of scenario planning, adaptive management, and the acceptance of uncertainty and of uncontrollability. Key words and actions are sustainability, human development, biosphere integrity, road maps and scenario planning, NOT efficiency and maximum yield. All of society needs a deeper and more community sense of social and environmental roles forming “communities of practice” where possible.

3. Value of the COP process

We probably recognize with Driss El Yazami, Head of Civil Society activities during the COP22, the crucial and basic elements of COP22 and the problems and needs of Africa. It is through the deeper sense of humanity that he calls for the “universalism” that enables all to act together “even if the historic responsibilities and future effects are not equally shared.”

4. The compassion and practice of Laudato si’

Laudato si’ placed the environment and the poor at the center of climate change and sustainable development discussions. In the Catholic world in Asia Pacific, where if translated and shared, it is first an experience of felt compassion for the poor that someone shares their pain and suffering.

The ecological conversion needed to bring about lasting change is also a community conversion to a new way of practicing change together and first entails gratitude and recognition that the world is gift.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Pedro Walpole, SJ, is the Coordinator of the Reconciliation with Creation program of the Jesuit Conference Asia Pacific.

|