This is not a new idea. The Buddha taught about the importance of right speech, the root of Abracadabra lies in the ancient Hebrew phrase ‘ ’ or ‘I create as I speak’ and the Gospel of John begins with those immortal words ‘In the beginning there was the word and the word was God.’ To have language is to have the power to express, name, label, categorise and define things, people, experiences and feelings.

’ or ‘I create as I speak’ and the Gospel of John begins with those immortal words ‘In the beginning there was the word and the word was God.’ To have language is to have the power to express, name, label, categorise and define things, people, experiences and feelings.

And these words have power.

We can be caught forever in the thrall of a psychiatric diagnosis or teacher’s remark, moving from being ‘lively’ to being a ‘naughty’ child in a single breath. Every word comes with its own baggage and its own history. Some words cannot be spoken because they hold so much weight, whilst others are moving into common speech as the passage of time wears away old meanings and clothes them in new.

To use an old English phrase, we each have our own word-hoard – a store of words collected from our parents, carers, siblings, teachers, peers, the books we read, the programmes we watch. We can then draw from this stock to communicate and express.

In times of extreme or unusual emotional states — the pain of loss or the ecstasy of birth — we often find our word hoards insufficient. When our lover leaves us, when we are struck with that strange yearning to be something or somewhere we are not, when we meet the inevitable end of life, we turn to the poets to offer us the magic combination of words that provide the image or the rhythm that expresses where we are — that resonates at our level of feeling.

Language is more than functional; it is an essential tool in the gardening shed of the soul.

But maybe it isn’t a word-hoard at all. Word hoard conjures to mind some sort of pantry or chest — quite possibly very old and wooden and filled with bio dynamic, organic apples, but cut off and not-living nonetheless. And language is living; it is a constantly evolving ecosystem — a word-wood.

As we grow, our word-wood grows. If we are lucky, the earth beneath our word-wood is made fertile by those around us. If we are unlucky, the earth is grey and cold; in that scrubland, bramble words grow, filling our mouths with dry, spiky, withered attempts to express the fire within. We swear, scream and hit because we have nothing else. These are the children who lash out in frustration because they don’t have the words to help us understand how they are feeling — the force of the absent word rises like a tsunami of the soul.

Word-wood soil can be enlivened with the right treatment — the right authors, speakers, words and phrases being introduced in the right way — but just as easily a fertile landscape can be destroyed by carelessness and commercial consumption. Monoculture language creeps in promising better communication through over simplification, manipulation through vile advertising, or utter confusion through ‘specialised’ jargon. Invasive species spring up — the word ‘like’ is the ground elder of speech — and GM word crops slowly change the natural landscape of our language and in doing so, redefine our internal and external experience of the world.

Robert Macfarlane recently reminded us of how many words we are losing in the UK on a daily basis and the danger that poses to the future of our countryside: ‘[We are in] an age when a junior dictionary finds room for “broadband” but has no place for “bluebell'”. What will happen when children can no longer name Oak or Beech, Sparrow or Robin? Will they wish to protect an area of nameless land inhabited by nameless creatures?

To take away a person’s name is to ‘de-humanise’, making it easier to avoid any sort of messy emotional attachment and opening the ‘thing’ up to exploitation, abuse or extermination. If we are losing the lexicon of the natural world, is it any wonder that rainforests full of trees, insects and animals are being destroyed by CEOs of foreign companies who have reduced the entire, living ecosystem of the Amazon to a ‘commodity’?

Mythologist Martin Shaw encourages his students to develop a practice of giving twelve secret names to the plants, animals or ‘things’ they encounter in nature and to speak those names out loud. He comments that ‘inventive speech appears to be a kind of catnip to the living world’ — an enlivening force. And surely it must be seen that those that love and know the land they live upon have a hundred names for snow or twenty different names mud or, at the very least, three different names for the garden robin. In giving something a name, we deepen our relationship with it and in finding many names we find ourselves watching, listening, thinking more deeply about that bird, plant, flower or bug — by engaging through language, we come to know it better.

So get out there and find the folkloric name of the hill behind your house, or watch the little plant determinedly pushing its head between the pavement cracks and realise that the word ‘daisy’ just isn’t enough to encapsulate that being. In opening ourselves to language as a dynamic force, rather than just a communication tool, we can begin to experience the world in a new and deeper way.

Now, a language is not just a body of vocabulary or a set of grammatical rules. A language is a flash of the human spirit. It’s a vehicle through which the soul of each particular culture comes into the material world. Every language is an old-growth forest of the mind, a watershed, a thought, an ecosystem of spiritual possibilities.

— Wade Davis, anthropologist and explorer

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Abbie Simmonds is a writer, teacher and student of myth. She is convinced that her enthusiasm for shamanic mythology, commitment to education and desire for a deeper connection to the environment will all come together if she goes on enough walks and reads enough books. Abbie lives and works in between Ditchling Beacon and the Seven Sisters and tries to spend as much time outside as possible. When she is not outside, she is usually in a school teaching teenagers words, story and self.

|

The False Promise of Economic Growth

George Monbiot

This article was originally published in

George Monbiot and

The Guardian, 24 November 2015

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

"We can persuade ourselves that we are living on thin air, floating through a weightless economy. But it’s an illusion."

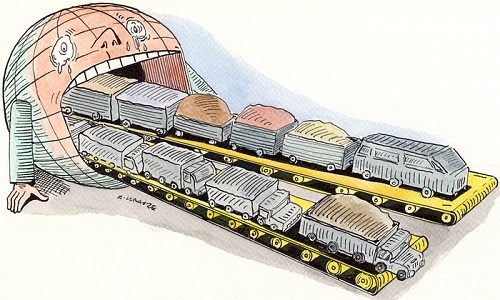

Illustration: Andrzej Krauze

|

Consume more, conserve more: sorry, but we just can’t do both. The belief that economic growth can be detached from destruction appears to be based on a simple accounting mistake. Economic growth is tearing the planet apart, and new research suggests that it can’t be reconciled with sustainability.

We can have it all; that is the promise of our age. We can own every gadget we are capable of imagining – and quite a few that we are not. We can live like monarchs without compromising the Earth’s capacity to sustain us. The promise that makes all this possible is that as economies develop, they become more efficient in their use of resources. In other words, they decouple.

There are two kinds of decoupling: relative and absolute. Relative decoupling means using less stuff with every unit of economic growth. Absolute decoupling means a total reduction in the use of resources, even though the economy continues to grow. Almost all economists believe that decoupling – relative or absolute – is an inexorable feature of economic growth.

On this notion rests the concept of sustainable development. It sits at the heart of the climate talks in Paris next month and of every other summit on environmental issues. But it appears to be unfounded.

A paper published earlier this year in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences proposes that even the relative decoupling we claim to have achieved is an artefact of false accounting. It points out that governments and economists have measured our impacts in a way that seems irrational.

Here’s how the false accounting works. It takes the raw materials we extract in our own countries, adds them to our imports of stuff from other countries, then subtracts our exports, to end up with something called “domestic material consumption”. But by measuring only the products shifted from one nation to another, rather than the raw materials needed to create those products, it greatly underestimates the total use of resources by the rich nations.

For example, if ores are mined and processed at home, these raw materials, as well as the machinery and infrastructure used to make finished metal, are included in the domestic material consumption accounts. But if we buy a finished product from abroad, only the weight of the metal is counted. So as mining and manufacturing shift from countries like the UK and the US to countries like China and India, the rich nations appear to be using fewer resources. A more rational measure, called the “material footprint”, includes all the raw materials an economy uses, wherever they happen to be extracted. When these are taken into account, the apparent improvements in efficiency disappear.

In the UK, for example, the absolute decoupling that the domestic material consumption accounts appear to show is replaced with an entirely different chart. Not only is there no absolute decoupling; there is no relative decoupling either. In fact, until the financial crisis in 2007, the graph was heading in the opposite direction: even relative to the rise in our gross domestic product, our economy was becoming less efficient in its use of materials. Against all predictions, a re-coupling was taking place.

While the OECD has claimed that the richest countries have halved the intensity with which they use resources, the new analysis suggests that in the EU, the US, Japan and the other rich nations, there have been “no improvements in resource productivity at all”. This is astonishing news. It appears to makes a nonsense of everything we have been told about the trajectory of our environmental impacts.

I sent the paper to one of Britain’s leading thinkers on this issue, Chris Goodall, who has argued that the UK appears to have reached “peak stuff”: in other words that there has been a total reduction in our use of resources, otherwise known as absolute decoupling. What did he think?

To his great credit, he responded that “broadly, of course, they are right”, even though the new analysis appears to undermine the case he has made. He did have some reservations, however, particularly about the way in which the impacts of construction are calculated. I also consulted the country’s leading academic expert on the subject, Professor John Barrett. He told me that he and his colleagues had conducted a similar analysis, in this case of the UK’s energy use and greenhouse gas emissions “and we find a similar pattern.” One of his papers reveals that while the UK’s carbon dioxide emissions officially fell by 194 million tonnes between 1990 and 2012, this apparent reduction is more than cancelled out by the CO2 we commission through buying stuff from abroad. This rose by 280m tonnes in the same period.

Dozens of other papers come to similar conclusions. For example, a report published in the journal Global Environmental Change found that with every doubling of income, a country needs one third more land and ocean to support its economy, because of the rise in its consumption of animal products. A recent paper in the journal Resources found that the global consumption of materials has risen by 94% over 30 years, and has accelerated since 2000. “For the past 10 years, not even a relative decoupling was achieved on the global level.”

We can persuade ourselves that we are living on thin air, floating through a weightless economy, as gullible futurologists predicted in the 1990s. But it’s an illusion, created by the irrational accounting of our environmental impacts. This illusion permits an apparent reconciliation of incompatible policies.

Governments urge us both to consume more and to conserve more. We must extract more fossil fuel from the ground, but burn less of it. We should reduce, reuse and recycle the stuff that enters our homes, and at the same time increase, discard and replace it. How else can the consumer economy grow? We should eat less meat, to protect the living planet, and eat more meat, to boost the farming industry. These policies are irreconcilable. The new analyses suggest that economic growth is the problem, whether or not the word sustainable is bolted to the front of it.

It’s not just that we don’t address this contradiction. Scarcely anyone dares even to name it. It’s as if the issue is too big, too frightening to contemplate. We seem unable to face the fact that our utopia is also our dystopia; that production appears to be indistinguishable from destruction.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

George Monbiot is an English writer, known for his environmental and political activism. He the author of the bestselling books The Age of Consent: A Manifesto for a New World Order, Captive State: The Corporate Takeover of Britain, and Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewilding, as well as the investigative travel books Poisoned Arrows, Amazon Watershed and No Man's Land. He blogs on the environment, social justice, and other issues.

|

International Community Attempts to

Negotiate with Nature in Paris

Nat Parry

This article was originally published in

Essential Opinion and Consortium News, 1 December 2015

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

"Near Boiling Point on Global Warming"

|

Editor's Note: This article was written in anticipation of the Paris Climate Summit.

Rising global temperatures – if they exceed 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels – threaten to unleash havoc across the planet, including mass dislocations of desperate people that will make the current flood of Syrian refugees look like a tiny warm-up.

With more than 40,000 negotiators from 196 governments descending on Paris this week to negotiate a comprehensive accord to tackle climate change, it is hard to imagine that they could possibly reach an agreement that will satisfy everybody.

The interests that each country brings to the table are so complex and diverse – especially when it comes to the touchy subjects of climate reparations and ensuring effective enforcement mechanisms for any sort of “binding” deal on how to actually reduce carbon emissions to safe levels – it is inconceivable that everyone (or anyone) will feel content at the end of these marathon negotiations in two weeks.

This is likely why the executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, a Costa Rican diplomat named Christiana Figueres, has for months been lowering expectations for the outcome of the summit.

While the goal of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) has long been deemed necessary to avoid the most serious effects of climate change – a future of drowned cities, desertifying croplands, and collapsing ecosystems – Figueres acknowledges that the negotiations, based on the declared “intended nationally determined contributions” (INDCs) of each country at the table, will probably not result in reaching that 2-degree goal.

“I’ve already warned people in the press,” she said this summer. “If anyone comes to Paris and has a Eureka moment — ‘Oh, my God, the INDCs do not take us to 2 degrees!’ — I will chop the head off whoever publishes that. Because I’ve been saying this for a year and a half.”

As Politico explains it, rather than reaching 2-degree goal, “What would be a success for Figueres, the UN and many of the countries taking part is setting in motion a process starting in 2020 that ups greenhouse gas cuts over time. Figueres calls it ‘the start of a long journey.’”

While it is true that taking the first step of this “long journey” is obviously necessary – and long overdue – in order to begin the process of mitigating climate change, and in that sense it is worth maintaining some optimism and positive thinking, what is less clear is whether nature will be as patient and understanding.

What the international community seems to be forgetting is that the environment is governed by natural laws and if the science is correct regarding global warming, we cannot continue to postpone meaningful action on tackling climate change. Indeed, it is clear that the effects of climate change are already taking hold in major ways and are only expected to get worse, with large parts of the planet potentially rendered uninhabitable, according to the world’s leading climate scientists.

Yet, an uninhabitable planet is what we should expect if participants in Paris fail to reach an ambitious and binding agreement this month that puts science and nature ahead of politics and profits. In this sense, the 40,000 negotiators engaging in two weeks of discussions and horse-trading in the French capital are not really negotiating with each other, but with Mother Nature. And the fact is, there is no reason to think that Mother Nature is willing or able to wait for humanity to start drastically reducing its carbon output.

As one analyst explains it, however, “emissions reductions are barely on the table at all” in Paris, with the talks essentially “rigged to ensure an agreement is reached regardless of how little action countries plan to take.” Because each submission for the reduction of carbon output is at the discretion of individual countries, “there is no objective standard it must meet or emissions reduction it must achieve.”

The “Climate Action Tracker,” a scientific assessment service that tracks countries’ emission commitments, offers an independent assessment estimating that the current national submissions, if fully implemented, could bring warming down to a 2.7 degree increase (above pre-industrial levels) by the end of the century. While this marks substantial progress from previous years, it is still only one third to half way to reaching the 2-degree-increase benchmark that has been deemed necessary to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

In other words, it’s as if a heavy smoker has been advised by his doctor to give up cigarettes but instead of quitting he simply makes a vague commitment to cut down a bit. This might seem like an improvement in the mind of the smoker, but the ultimate outcome remains the same: severe health problems and an early death.

Of course, the 2-degree-increase threshold that we are set to surpass under current emission targets will just usher in the “worst effects” of climate change – but consider how many effects we are already experiencing, having just broken the 1-degree threshold earlier this year. As a UN report recently documented, “Weather-related disasters are becoming increasingly frequent, due largely to a sustained rise in the numbers of floods and storms.”

Examining the past two decades of data, the landmark report “The Human Cost of Weather-Related Disasters 1995-2015” found that flooding accounted for 47 percent of all weather-related disasters, affecting 2.3 billion people. Storms killed more than 242,000 people in the 20-year time period, with the vast majority of these deaths (89 percent) occurring in lower-income countries. Heatwaves and extreme cold were also particularly deadly, with high-income countries reporting that 76 percent of weather-related disaster deaths were due to extreme temperatures, mainly heatwaves.

The report notes that due to the high number of variables in climate science and extreme weather, “scientists cannot calculate what percentage of this rise is due to climate change” but points out “that predictions of more extreme weather in the future almost certainly mean that we will witness a continued upward trend in weather-related disasters in the decades ahead.”

A World Bank report, “Turn Down the Heat: Why a 4°C Warmer World Must be Avoided,” is equally stark, warning that we’re on track for a world marked by extreme heatwaves, declining global food stocks, loss of ecosystems and biodiversity, and life-threatening sea level rise.

“A 4-degree warmer world can, and must be, avoided – we need to hold warming below 2 degrees Celsius,” said World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim in 2012. “Lack of action on climate change threatens to make the world our children inherit a completely different world than we are living in today.”

Besides extreme weather, there are also the compounding security threats associated with climate change, with the Council on Foreign Relations – for one – warning as far back as 2007 that climate change was contributing significantly to terrorism and conflict. The organization noted that “declining food production, extreme weather events, and drought from climate change” could “contribute to massive migration and possibly state failure, leaving ‘ungoverned spaces’ where terrorists can organize.”

These concerns have also been raised by the Pentagon, which refers to climate change as a “threat multiplier” because it “has the potential to exacerbate many of the challenges we are dealing with today – from infectious disease to terrorism.”

In fact, it is well-documented that the current conflict in Syria, which has facilitated the rise of the Islamic State and led to Europe’s biggest refugee crisis since World War Two, was triggered by a series of factors, including climate change.

According to a recent report called “A New Climate for Peace,” an independent study commissioned by the foreign ministers of the G7 nations, a severe drought that hit Syria in 2006 was exacerbated by resource mismanagement and the impact of climate change on water and crop production.

The resulting food insecurity was “one of the factors that pushed the country over the threshold into violent conflict,” and now is the source of hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants seeking asylum in European nations, which are evidently ill-prepared to deal with the influx.

Indeed, having recently witnessed the European Union’s dysfunctional response to the Syrian refugee crisis, one wonders what the reaction will be like once people truly start to leave their homes en masse due to global warming, with 150 million “climate refugees” expected by 2050, according to the Environmental Justice Foundation.

The truth is, when it comes to global warming and related environmental, security and environmental concerns, these matters are simply not up for negotiation. If we accept the reality of human-induced climate change – as nearly 100 percent of scientists do – we must address the issue in the most ambitious manner possible in order to ensure a planet that is even remotely livable for ourselves, for our children and for their children.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nat Parry is the co-author of Neck Deep: The Disastrous Presidency of George W. Bush. He has been editorial director of the OSCE PA International Secretariat, co-ordinating the work of the Research Fellows, producing content for and designing the layout of OSCE PA publications, and providing general support for the PA communications office. Prior to joining the Secretariat, Parry held policy-related positions at American NGOs such as U.S. Public Interest Research Group and Public Citizen's Congress Watch, where he specialized in civil justice and campaign finance reform. He has also worked as Communications Specialist at the American Constitution Society for Law and Policy, Associate Editor at the Consortium for Independent Journalism and as a freelance writer for a variety of publications. He holds a master's degree in political science and a bachelor's degree in history from George Mason University.

|

|Back to TITLE|

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Supplement 1

Supplement 2

Supplement 3

Supplement 4

Supplement 5

Supplement 6

PelicanWeb Home Page