A straightforward line of reasoning demonstrates that the only viable explanation of postindustrial warming is an anthropogenic source. This explanation is compatible with the “pause” in the warming since 1998, and it demonstrates that, in a statistical sense, such a pause is extremely likely. Credit: Shaun Lovejoy

|

Global warming science has concentrated on proving the theory that the postindustrial warming is largely caused by human activities. Yet no scientific theory can be proved beyond all doubt, and our attempts to convince people of the science are entering a period of diminishing returns.

For example, the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5, 2013) of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reiterated its 2007 statement “that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century,” only upgrading it from “likely” to “extremely likely.” Meanwhile, those who reject this anthropogenic hypothesis have continued to push their theory that the warming is a giant fluctuation of solar, nonlinear dynamics that are internal to the atmosphere or other natural origin. For brevity we will call this group the “denialists,” following the suggestion of Gillis [2015].

Although no scientific theory can ever be proved in a mathematically rigorous sense, even elegant theories can be disproved by a single decisive experiment.

|

In order to end the scientific part of the debate—to reach “climate closure”—it is therefore necessary to demonstrate that the giant fluctuation theory has such a low probability that we can confidently dismiss it. To do this, we can use a fundamental asymmetry in scientific methodology: although no scientific theory can ever be proved in a mathematically rigorous sense, even elegant theories can be disproved by a single decisive experiment.

Below, we summarize a straightforward disproof that achieves this closure so that the only viable explanation of the warming is anthropogenic [Lovejoy, 2014a, 2014b, 2015; hereinafter L1, L2, L3]. The same methodology also shows how the anthropogenic theory is compatible with the “pause” in the warming since 1998 and, indeed, in a statistical sense, that such a pause is extremely likely. As a bonus, denialist arguments based on the uncertainties of complex numerical models are rendered irrelevant because this demonstration does not require these models [Lemos and Rood, 2010; Norton and Suppe, 2001]. Finally, the basic argument can be understood by the lay public.

A Simple Approach to Determine Human Effects

The effects of climate forcings are difficult to quantify and contribute to the large model uncertainties. However, since 1880, the forcings have been linked to economics. To a good approximation, if you double the world economy, double the carbon dioxide (CO2), double the methane and aerosol outputs, and double the land use changes, you get double the warming. This justifies using the global CO2 forcing since 1880 as a linear surrogate for all the anthropogenic forcings (L1; using CO2 equivalent yields nearly identical results).

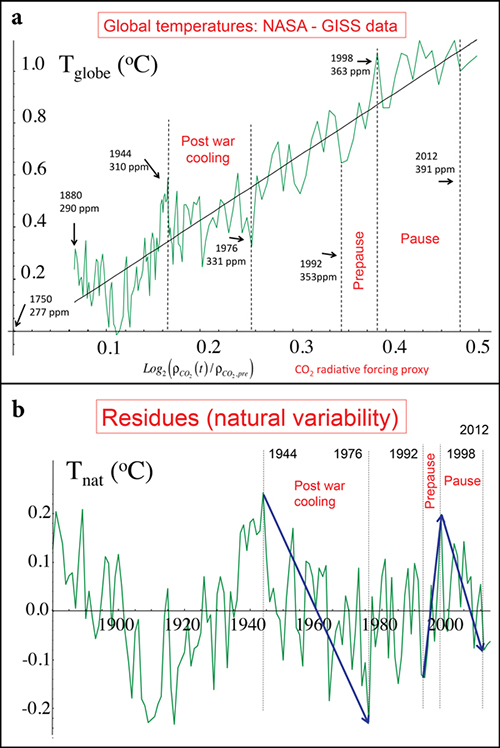

Fig. 1. (a) Global temperature anomalies (NASA, 1880–2013) as functions of radiative forcing using the carbon dioxide (CO2) forcing as a linear surrogate. The line has a slope of 2.33°C per CO2 doubling. Some dates and corresponding annually, globally averaged CO2 concentrations are indicated for reference. GISS, Goddard Institute for Space Studies; ppm, parts per million. Adapted from Lovejoy [2014b, Figure 1a]. (b) The residuals from the straight line in Figure 1a; these are the estimates of the natural variability. The vertical dashed lines are the same as in Figure 1a. The arrows indicate notable events. Adapted from Lovejoy [2014b, Figure 1c].

|

Figure 1a shows the global annual temperature plotted not as a function of the date, but rather as a function of the CO2 forcing. Even without fancy statistics or special knowledge, it is easy to see that the temperature (plotted in green) increases very nearly linearly with some additional fluctuations; these represent the natural variability. The slope (black), 2.33°C per CO2 doubling, is the actual historical increase in temperature due to the observed increase in CO2: the “effective climate sensitivity.” As a check on our assumptions, this figure sits comfortably in the IPCC range of 1.5°C–4.5°C per CO2 doubling for the (slightly different) “equilibrium climate sensitivity.”

The difference (residues) between the actual temperature and the anthropogenic part is the natural variability, which is plotted in Figure 1b. We can confirm that this is reasonable since the average amplitude of the residues (±0.109°C) winds up being virtually the same as the errors in 1-year global climate model hindcasts (±0.105°C and ±0.106°C from Smith et al. [2007] and Laepple et al. [2008], respectively). So knowing only the slope of Figure 1a and the global annual CO2, we could predict the global temperature for the next year to this accuracy (L3). Clearly, this residue must be close to the true natural variability.

Disproving Natural Causes

The range of the straight line in Figure 1a is an estimate of the total anthropogenic warming since 1880—about 1°C. What is the probability that the denialists are right and that this is simply a giant natural fluctuation? This would be a rare event but how rare?

To check that comparisons of the current period against the historical record are valid, L1 reconstructed records of volcanic and solar activity. That study concluded that the statistics of the industrial epoch variations are no different from the preindustrial ones. Volcanic activity was highly intermittent but no more so than usual; solar activity, which denialists often blame for the observed warming, has, if anything, diminished over the last 50 years [Foukal et al., 2006].

Then, L1 used preindustrial temperature series drawing on several sources to estimate the likelihood of a given amount of natural temperature change. Applying the usual statistical approach—the bell curve—to these data leads to the conclusion that the chance of a 1°C fluctuation over 125 years being natural is in the range of 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 3,000,000. This is a rough estimation: for long periods, the standard deviation of temperature differences is twice the 0.1°C value. Hence a 1°C fluctuation is about five standard deviations, or a 1 in 3,000,000 chance.

However, nonlinear geophysics tells us that the extremes should be far stronger than the usual bell curve allows. L1 shows that 1°C, century-long global-scale fluctuations are more than 100 times more likely than the bell curve would predict. This gives a probability of at most 1 in 1000, which is still small enough to confidently reject this possibility.

A Necessary “Pause”

One can apply the same type of analysis to the hiatus in the warming (the relatively flat part of the fluctuating line in Figure 1a after 1998), also referred to as the pause. Figure 1b shows that it is actually a natural cooling event sufficiently large (˜0.3°C) that it has masked the more or less equal anthropogenic warming over the period.

Although this cooling is somewhat unusual, it is not rare: similar 15-year coolings have a natural return period of 20–50 years.

|

Although this cooling is somewhat unusual, it is not rare: statistical analysis shows that similar 15-year coolings have a natural return period of 20–50 years (L2). Additionally, in this case, the cooling immediately follows the even larger prepause warming event (1992–1998; Figure 1b). That is, the pause is no more than a return to the mean; it can be accurately hindcast (L3).

Alternatively, Karl et al. [2015] has recently produced a temperature series with new ocean and other bias corrections. In this warmer series, the amplitude of the corresponding natural cooling is 0.09°C less than that shown in Figure 1b. Since the return period for this smaller natural cooling is only about 10 years (L2, Figure 2), decadal trends cannot (and did not) detect any statistically significant pause at all.

In any case, far from supporting denialist claims that the warming is over, this return is a necessary consequence of the theory of anthropogenic warming that predicts that the natural variability will cause fluctuations to stay near the long-term anthropogenic trend in Figure 1: without it, the warming would have soon become unrealistically strong.

Quod Erat Demonstrandum

The scientific method is much more effective at rejecting false hypotheses than in proving true ones. By estimating the probabilities of centennial-scale preindustrial temperature changes, with 99.9% confidence we are able to reject the denialist hypothesis that the industrial age warming was from solar, volcanic, or other natural causes, leaving anthropogenic origin as the only alternative.

The scientific debate is now over; the moment of closure has arrived. Although climate scientists must move on to pressing scientific questions such as regional climate projections and the space–time variability, our species must tackle the urgent issue of reducing emissions and mitigating the consequences of the warming.

References

Foukal, P., C. Frohlich, H. Spruit, and T. Wigley (2006), Variations in solar luminosity and their effect on the Earth’s climate, Nature, 443, 161–166, doi: doi:10.1038/nature05072408.

Gillis, J. (2015), Verbal warming: Labels in the climate debate, New York Times, 12 Feb.

Karl, T. R., A. Arguez, B. Huang, J. H. Lawrimore, J. R. McMahon, M. J. Menne, T. C. Peterson, R. S. Vose, and H.-M. Zhang (2015), Possible artifacts of data biases in the recent global surface warming hiatus, Science, 348, 1469–1472, doi:10.1126/science.aaa5632.

Laepple, T., S. Jewson, and K. Coughlin (2008), Interannual temperature predictions using the CMIP3 multi-model ensemble mean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, L10701, doi:10.1029/2008GL033576.

Lemos, M. C., and R. B. Rood (2010), Climate projections and their impact on policy and practice, WIREs Clim Change, 1, 670–682.

Lovejoy, S. (2014a), Scaling fluctuation analysis and statistical hypothesis testing of anthropogenic warming, Clim. Dyn., 42, 2339–2351, doi:10.1007/s00382-014-2128-2.

Lovejoy, S. (2014b), Return periods of global climate fluctuations and the pause, Geophys. Res. Lett., 41, 4704–4710, doi:10.1002/2014GL060478.

Lovejoy, S. (2015), Using scaling for macroweather forecasting including the pause, Geophys. Res. Lett., doi:10.1002/2015GL065665, in press.

Norton, S. D., and F. Suppe (2001), Why atmospheric modelling is good science, in Changing the Atmosphere: Expert Knowledge and Environmental Governance, edited by P. N. Edwards and C. A. Miller, 385 pp., MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Smith, D. M., S. Cusack, A. W. Colman, C. K. Folland, G. R. Harris, and J. M. Murphy (2007), Improved surface temperature prediction for the coming decade from a global climate model, Science, 317, 796–799.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shaun Lovejoy is Professor of Physics, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; email:

lovejoy@physics.mcgill.ca

|

After 70 Years: The UN Falls Short, and Yet...

Richard Falk

This article was originally published in

MWC News, 8 October 2015

under a Creative Commons License

When the UN was established in the aftermath of the Second World War hopes were high that this new world organization would be a major force in world politics, and fulfill its Preamble pledge to prevent future wars. Seventy years later the UN disappoints many, and bores even more, appearing to be nothing more that a gathering place for the politically powerful.

I think such a negative image has taken hold because the UN these days seems more than ever like a spectator than a political actor in the several crises that dominate the current agenda of global politics. This impression of paralysis and impotence has risen to new heights in recent years.

When we consider the waves of migrants fleeing war torn countries in the Middle East and Africa or four years of devastating civil war in Syria or 68 years of failure to find a solution for the Israel/Palestine conflict or the inability to shape a treaty to rid the world of nuclear weapons, and on and on, it becomes clear that the UN is not living up to the expectations created by its own Charter and the fervent hopes of people around the world yearning for peace and justice.

The UN itself seems unreformable, unable to adapt its structures and operations to changes in the global setting. The Security Council’s five permanent members are still the five winners in World War II, taking no account of the rise of India, Brazil, Indonesia, Nigeria or even the European Union. Despite globalization and the transnational rise of civil society, states and only states are eligible for UN membership and meaningful participation in the multifold operations of the Organization.

How can we explain this disappointment? We must at the outset acknowledge that the high hopes attached to the UN early on were never realistic. After all, the Charter itself acknowledged the geopolitical major premise, which is the radical inequality of sovereign states when it comes to power and wealth. Five permanent seats in the Security Council were set aside for these actors that seemed dominant in 1945. More importantly, they were given an unrestricted right to veto any decision that went against their interests or values, or those of its allies and friends. In effect, the constitution of the Organization endowed the potentially most dangerous states in the world, at least as measured by war making capabilities, with the option of being exempt from UN authority and international law.

Such an architectural feature of the UN was not a quixotic oversight of the founders. It was a deliberate step taken to overcome what perceived to be a weakness of the League of Nations established after World War I, which did look upon the equality of sovereign states as the unchallengeable constitutional foundation of an organization dedicated to preserving international peace. The experience of the League was interpreted as discouraging the most powerful states from meaningful participation (and in the case of the United States, from any participation at all) precisely because their geopolitical role was not taken into account.

In practice over the life of the UN, the veto has had a crippling political effect as it has meant that the UN cannot make any strong response unless the permanent five (P5) agree, which as we have learned during the Cold War and even since, is not very often. There is little doubt that without the veto possessed by Russia the UN would have been far more assertive in relation to the Syrian catastrophe, and not found itself confined to offering its good offices to a regime in Damascus that never seemed sincere about ending the violence or finding a political solution except on its own harsh terms of all out defeat of its adversaries.

Of course, the General Assembly, which brings all 194 member states together, supposedly has the authority to make recommendations, and act when the Security Council is blocked. It has not worked out that way. After the General Assembly flexed its muscles in the early 1970s emboldened by the outcome of the main colonial wars geopolitics took over. The GA became a venue controlled by the non-aligned movement, and in 1974 when it found backing for the Declaration of a New International Economic Order the writing was on the wall.

The larger capitalist states fought back, and were able to pull enough strings to ensure that almost all authority to take action became concentrated in the Security Council. The Soviet Union went along, worried about political majorities against its interests, and comfortable with the availability of the veto as needed. The General Assembly has been since mainly relegated to serving the world as a talk shop, and is hardly noticed when it comes to crisis management or lawmaking. Despite this development the GA is still relevant to the formation of world public opinion. Its Autumn session provides the leaders of the world with the most influential lectern at which to express their worldview and recommendations for the future. Even Pope Francis took advantage of such an influential platform on which to articulate his concerns, hopes, and prescriptions.

There is an additional fundamental explanation of why the UN cannot do more in response to the global crises that are bringing such widespread human suffering to many peoples in the world. The UN was constructed on the basis of mutual and legally unconditional respect for the territorial sovereignty of its members. The Charter itself in Article 2(7) prohibits the UN from intervening in matters that are essentially internal to a state, such as strife, insurgency, abridgement of human rights, and even civil war. Such an insulation of domestic strife runs counter to the practice of intervention by geopolitical actors, and in this respect gives the UN framework a legalistic character that is not descriptive of the manner in which world politics operates.

True, when the political winds blow strongly in certain threatening directions as was the case in relation to Serbian behavior in Kosovo that seemed to be on the verge of repeating the Srebrenica massacre of 1995, NATO effectively intervened but without the blessings of the UN, and hence in violation of international law.

Then again in Libya the Security Council actually gave its approval for a limited intervention in the form of a no-fly-zone to avoid a humanitarian catastrophe befalling the besieged inhabitants of Benghazi. In that setting, the SC relying on the new norm of ‘responsibility-to-protect’ or R2P to justify its use of force. When NATO immediately converted this limited UN mandate into a regime-changing intervention that led to the execution of Qaddafi and the replacement of the Libyan government it was clear that the R2P argument acted as little more than a pretext to pursue a more ambitious, yet legally dubious and politically unacceptable, Western agenda in the country. R2P diplomacy has been further discredited by the failure to offer UN protection in the extreme circumstances of Palestine, Syria, and now Yemen.

Not surprisingly, Russia and China that had been persuaded by Western powers in 2011 to go along with the establishment of a no-fly-zone to protect Benghazi felt deceived and manipulated. These governments lost their trust in the capacity of the Security Council to set limits that would be respected once a decision was reached. This is part of the story of why the UN has been gridlocked when it came to Syria, and why R2P has been kept on the diplomatic shelf.

It is helpful to appreciate that disappointment with the role of the UN is usually less the fault of the Organization than of the behavior of the geopolitical heavyweights. If we want a stronger UN then it will be necessary to constrain geopolitics, and make all states, including the P5 subject to the restraints of international law and sensitive to moral imperatives.

|

The Security Council to be able to overcome the veto depends upon trust among the P5 sufficient to achieve a consensus, which was badly betrayed by what NATO did in Libya. Human rights advocates have long put forward the idea that the P5 agree informally or by formal resolution to forego the use of the veto in devising responses to mass atrocities, but so far, there has been little resonance. Similarly, sensible proposals to establish an UN Peace Force that could respond quickly to natural and humanitarian catastrophes on the originating initiative of the UN Secretary General have also not found much political resonance over the years. It would seem that the P5 are unwilling to relax their grip on the geopolitical reins on UN authority established in the very different world situation that existed in 1945.

Kosovo showed that, at times, humanitarian pressures (when reinforcing dominant geopolitical interests) induce states to act outside the UN framework, while Libya illustrates the long term weakening of UN capacity and legitimacy by manipulating the debate to gain support of skeptical states for intervention in an immediate war/peace and human rights situation. The hypocrisy of the R2P diplomacy by the failure to make a protective response of any kind to the acute vulnerability of such abused minorities as the Uighurs in Xinjiang Province of China, the Rohingya in Rankhine State of Myanmar, and of course the Palestinians of Palestine. There are, of course, many other victimized groups whose rights are trampled upon by the state apparatus of control that for UN purposes is treated as their sole and unreviewable legal protector.

In the end, what this pattern adds up to is a clear demonstration of the persisting primacy of geopolitics within the UN. When the P5 agree, the UN can generally do whatever the consensus mandates, although it technically requires additional support from non-permanent members of the SC. If there is no agreement, then the UN is paralyzed when it comes to action, and geopolitical actors have a political option of acting unlawfully, that is, without obtaining prior authority from the Security Council and in contravention of international law. This happened in 2003 when the U.S. Government failed to gain support from the SC for its proposed military attack upon Iraq, and went ahead anyway, with disastrous results for itself, and even more so for the Iraqi people.

It is helpful to appreciate that disappointment with the role of the UN is usually less the fault of the Organization than of the behavior of the geopolitical heavyweights. If we want a stronger UN then it will be necessary to constrain geopolitics, and make all states, including the P5 subject to the restraints of international law and sensitive to moral imperatives.

Another kind of UN reform that should have been achieved decades ago is to make the P5 into the P8 or P9 by enlarging permanent membership to include a member from Asia (additional to China), Africa, and Latin America. This would give the Security Council and the UN more legitimacy in a post-colonial world where shifts in the global balance are still suppressed.

Along with the above explanation of public disappointment, there are also many reasons to be grateful for the existence of the UN and to be thankful that despite the many conflicts in the world during its lifetime every state in the world has wanted to become a member, and none have exhibited their displeasure with UN policies to leave the Organization. Given the intensity of conflict in the world, sustaining this universality is itself a remarkable achievement. It perhaps expresses the unanticipated significance of the UN as the most influential and versatile hub for global communications.

There are other major UN contributions to human wellbeing. The UN has been principally responsible for the rise of human rights and environmental protection, and has done much to improve global health, preserve cultural heritage, protect children, and inform us about the hazards of ignoring climate change.

We could live better with a stronger UN, but we would be far worse off if the UN didn’t exist or collapsed. The only constructive approach is to do our best in the years ahead to make the UN more effective, less victimized by geopolitical maneuvering, and more attuned to achieving humane global governance.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Falk is Albert G. Milbank Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University and Visiting Distinguished Professor in Global and International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has authored and edited numerous publications spanning a period of five decades, most recently editing the volume International Law and the Third World: Reshaping Justice (Routledge, 2008). He is currently serving his third year of a six year term as a United Nations Special Rapporteur on Palestinian human rights.

|

Living in the Anthropocene – A Frame for New Activism

Mark Garavan

This article was originally published in

Feasta, 26 October 2015

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

We are living in a new time. A new world has emerged. Like many things that are new on such a scale it is at once frightening, disturbing, uncomfortable. We have emerged from the geological epoch of the Holocene into a new epoch designated as the Anthropocene.[1] This notion of the Anthropocene refers to a profound realisation that human aggregate activity is now the single most decisive force shaping the planet. We have become the most significant geological agent acting on the Earth. For better or worse we have broken through a certain limit and possess now the power to determine the biosphere of the planet.

In the Anthropocene the old simplicities are gone. We are no longer human subjects acting upon an objective nature ‘outside’ us. Nature and human are now bound together. Free nature is over. Free humanity is over. They are relics of the Holocene. In our new age, Earth and Human are entangled irrevocably together. Welcome to the era of Earth-bound responsibility! The assumptions, the myths, the illusions of the Holocene no longer apply.

This recognition of a new epoch is not the result of argument or claim or campaign. It is not a question of belief, unless one thinks one must believe in reality itself. The new age is grounded in a measurable and observable set of facts, facts on such a scale as to be beyond questions of faith. The difficulty in recognising the new epoch is therefore not one of evidence. Rather, the challenge before us is that the vast panoply of institutions, practices, ideologies and cultures which structure human meaning and behaviour are the product of the Holocene. Our dominant and still prevailing worldview is rooted in the epoch of climate stability and security where humans were a discrete species inhabiting the objective Earth as free subjects.

This no longer applies. The Holocene gave rise to all the great civilisations of human culture, the philosophies, the great religions. How can we possibly re-think all of this in the little time that epochal change offers us to adjust and adapt? Because what is at stake could not be clearer. Either we adapt to the reality of the Anthropocene or we collapse into the perils of extinction as yet another mal-adaptive life-form.

In this brief paper, which serves only as an introduction to a more comprehensive treatment, I will sketch in summary terms the implications of living in the Anthropocene. Knowing where we are is one of the most basic life-skills for dwelling on planet Earth. The challenge is to re-think and re-inhabit our planet. This challenge is for everyone even for those who consider themselves ’right’ on the environmental question. Environmentalism too must now radically change. The Anthropocene will sweep all of the Holocene before it including our notions of environmentalism and that old chestnut of comfort ‘sustainability’.

From Holocene to Anthropocene – a series of sketches

Before proceeding with my potted sketches (literally) it might be wise to outline some basic definitions. Relying, as one tends to do today, on Wikipedia the Holocene can be defined as:

“… the geological epoch that began after the Pleistocene at approximately 11,700 years BP and continues to the present. The Holocene is part of the Quaternary period. Its name comes from the Greek words ???? (holos, whole or entire) and ?a???? (kainos, new), meaning “entirely recent”. It has been identified with the current warm period, known as MIS 1, and can be considered an interglacial in the current ice age based on that evidence. The Holocene also encompasses the growth and impacts of the human species worldwide, including all its written history, development of major civilizations, and overall significant transition toward urban living in the present. ”

The Anthropocene is defined as:

“… a proposed epoch that begins when human activities started to have a significant global impact on Earth’s ecosystems. The term – which appears to have been used by Russian scientists as early as the 1960s to refer to the Quaternary, the most recent geological Period – was coined with a different sense in the 1980s by ecologist Eugene F. Stoermer and has been widely popularized by atmospheric chemist, Paul Crutzen, who regards the influence of human behaviour on the Earth’s atmosphere in recent centuries as so significant as to constitute a new geological epoch for its lithosphere. As of April 2015, the term has not been adopted formally as part of the official nomenclature of the geological field of study.”

Less detached definitions of the Anthropocene include the following:

“A period marked by a regime change in the activity of industrial societies which began at the turn of the nineteenth century and which has caused global disruptions in the Earth System on a scale unprecedented in human history: climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution of the sea, land and air, resources depredation, land cover denudation, radical transformation of the ecumene, among others. These changes command a major realignment of our consciousness and worldviews, and call for different ways to inhabit the Earth.” [2]

Crucial to the identification of the Anthropocene is determining whether there is an objective, measurable impact on the planet, especially on its life-forms, which may be discoverable by scientists many centuries, indeed, millennia from today. Many scholars of this topic suggest that the detonation of test nuclear devices beginning in 1945 is precisely that – a clear marker of a new order of impact on the Earth’s very structure of life which will be forever present as an observable impact on the geological and biological record.

As noted in the definition above, the official, academic geological approval of this terminology is not yet achieved. That may occur in 2016 or not. Nonetheless, the heuristic and rhetorical potency of the Anthropocene has already had a significant impact on a raft of social sciences where it has become central concepts for theorists in history, sociology, anthropology, geography and philosophy.[3] It is not I hope too reckless a claim to suggest that the intellectual and conceptual space opened up by the identification of the Anthropocene is having a major innovative impact on the social sciences generally permitting theory to finally step beyond the modern and ‘post-modern’ epistemes of the 20th century. This new frame may also offer a decisive shift in our understanding of the ‘environment’ as merely something ‘out there which surrounds us’ and of environmentalism as a social and political movement.

The justification (at least within social science terms) for the Anthropocene may be best glimpsed in terms of whether something truly new has happened. If one may present cultural history in very crude and linear terms then a number of key human-nature movements can be discerned, at least within the Western historical trajectory. This after all is the trajectory that gave rise to modernity and has brought us to the impasse we presently find ourselves in.

The first movement within Indo-European culture was likely to have been that of animism – the notion of the Earth and ‘nature’ as teeming with multiple points of consciousness. The sensibility that arose seems to be one of either communing with, or placating, these nodes of spirit manifested within animate and inanimate forms of life.

The Judeo-Christian movement represented a significant change. Here was emphasised the notion of the human as ‘created’ by a supernatural being who is external to nature and Earth. The human stands apart from the rest of creation – present but absent, image of God but condemned to struggle within the brutal requirements of life on Earth.

Figure One: Human and Earth as separate

The image here is of the human separate and alienated from the Earth – a being destined ultimately for an unworldly heaven rather than an Earthling.

It is little wonder that this sensibility led inevitably to anthropocentrism – the Universe and the Earth seen in terms of their value to the human, the human as superior to, and above, brute, inanimate creation. The Cartesian revolution of the early 17th Century further augmented this view of human consciousness trumping mindless matter – cogitans above extensa.

Figure Two: Human superior to Earth

The license this gave to the human permitted the emergence of industrialism and capitalism. The Earth was now mere resource, mere empty space to be shaped and conquered and utilised for human development and progress. The empty formlessness of nature required human agency and expansion to give it meaning and value.

Figure Three: Human as exploiter/developer of an unlimited Earth

By the second half of the 20th Century it became clear to many that nature had in fact limits. Resources were in fact finite. Pollution could only go so far in terms of the planet’s carrying capacity. Human activity had to be at least tempered, rendered in the new jargon ‘sustainable’. Environmentalism as a modern sensibility was born.

Figure Four: Human reaches limit of Earth’s resources and carrying capacity

For many, indeed most, this remains the sensibility of today. We are caught in a world of exploitative limits. These limits are imposing stresses on us. We are told we merely need new policies and approaches. This sensibility still sees the human as subject and agent, confronting a nature external to us but affected by us. We exist in a relationship with nature. Our task is merely to learn to relate better.

But now, alas, we have indeed come to the end of this world. The new world begins with the recognition that nature as object, as free, as autonomous, is over. The line was crossed. There is no nature outside the human.[4] There is no human outside nature. Our impact is such that nature is us, is being fashioned by us. Rather than being inert recipients of our action, the Earth (Gaia) has stirred and is also now active, an agent in its own right, giving us feedback, responses, messages that we must receive. We are tied together now. There is no gap between us. The old human sensibility of the Holocene is no longer adequate. A new mode of being human is required, one that is profoundly responsible for all it does, but must be profoundly attentive to the new agent stirring and moving all around us – the Earth itself. We have entered the inter-subjective, multi-agential Anthropocene world. Shall we be terrified or exhilarated?

Birth of the Anthropocene

The Anthropocene began in a clear moment when human impact started to shape the planet’s very life-forms in a manner greater than any other discernible force or in a manner quicker and sharper than other agents. For our purposes now we can leave the argument to one side as to when this can be dated. Three key facts determine that unwittingly, unintentionally, we have fallen into a new world.

1. The planet, especially its bio-diversity, has been / is profoundly shaped by human behaviour – it is the single biggest force presently at play;

2. Climate change is occurring;

3. There is an absolute limit to economic growth.

The data on human global impact is simply staggering[5]. Bio-diversity, land use, water use, resource use, urbanisation, and so on, have been utterly altered by human behaviour. Almost nowhere lies outside the realm of human impact. Barely any life-form exists without the chemical markers of human activity. We are not one species among many. We are of a different order altogether.

Though the loss of bio-diversity is the largest single impact, our greatest recognition of the effect of human behaviour is possibly in climate change. Once this was a theory. Then a distinct possibility. Now it is our reality. It is underway. There is no credible scientific doubt. The only issue is how far it proceeds and how quickly. Will our climate alter in a continuous progression or tip suddenly into a new climatic steady-state? We do not know. Our models tell us one thing. The paleo-climate record tells us something else.

The point though is that climate (all our accumulated weather events over space and time) is no longer ‘natural’. It is us. We have made it like this. But altering climate is not simply changing weather patterns. Climate is nature, nature is culture. When the rains fall, where the rains fall, if the rains fall, determine the entire movements of civilisation.

The apparently safely inanimate background of climate and nature has stirred, has become animate. It addresses us, demands response. It is no longer reliable, predictable, secure. We have entered a world of inter-agency between the human and the non-human Earth. This is the Anthropocene. From once believing ourselves humans free upon a stable nature to do as we wish we find ourselves newly earth-bound, tied into the Earth itself, as part of it.

What is clear is that we cannot go on as before. The old mode of living, the mode developed in the Holocene, is no longer possible. Business as usual is not an option. At its most simple level our adherence to the goal of perpetual economic growth is rendered dysfunctional and literally impossible. Growth simply cannot be the paradigm for development in the Anthropocene. If U.S. standards of consumption were globalised then five separate Earths would be required to support it. But there is only one Earth. It just cannot be. We have hit the limit of the possible within the economic growth model. Capitalism has no place now other than as destroyer of a world.

Implications of the Anthropocene

Epochal shifts are extraordinary times. They are full of possibility. They are full of danger. Everything is possible. Nothing is guaranteed. The objectivity underlying the emergence of the Anthropocene does not nevertheless deliver us automatically into new modes of presence on the Earth, new forms of inter-species and human justice. Politics endures. Arguments continue. Options remain. Choices tantalise. In short, the Anthropocene could lead us to deliverance or doom.

The objective realisation of human-Earth entanglement and the limits that necessarily follow from that do not in themselves resolve matters. We remain beings who choose. Our choices are set by our perceptions of self-interest, by the immense inequalities and environmental injustices that exist among us and by the spontaneous framings of meaning and reality configured by our ideological perspectives. We cannot escape all of this. We cannot avoid the messiness of politics and argument. Human responsibility for our precipitation into the Anthropocene is not evenly distributed. The Western capitalist world is largely where responsibility lies and even there the fingers of judgement must point to those in the socio-economic upper tiers.

But what are we to do? How shall we fashion a civilisation fit for the Anthropocene when all of our Western cultural references and our institutions and practices are products of the Holocene. Even our dissenting discourses of Marxism, Feminism and Environmentalism are rooted in a Holocene conceptual framework whereby we perceive a human subjectivity significantly cut off from nature’s inert objectivity.

Everything is possible. Authoritarian Fascism all the way to new modes of intra-human and human- Earth solidarity and co-living lie open. But some things are clear. Some things must happen if extinction of the human project on Earth is to be avoided. Three immediate implications at least seem apparent.

1. We need to think!

2. We need to take the responsibility of being in the Anthropocene

3. We need to recognise that unlimited economic growth (i.e. Capitalism) is no longer possible as a sensible model for development

The notion that we need to think may seem banal. We live in a culture which values feeling, emotion, expression. Fast thought is all about us in soundbites, power-point slides, net-based summaries. It seems to me that we must return to thought, recover our innate human capacity to think our way out of challenge. Deep thinking is needed in a world where our sense of deep history is to be recovered or discovered. Human history begins in the depths of evolutionary time when the first eye emerged, the first ear, the first mammal limb, the first of each thing that makes us what we are. Our thinking is what enables us to inhabit reality – the world as it really is – and see past the murky atmosphere of symbolic and ideological interpellation. Here is the real task for a renewed education in the Anthropocene, one which prepares us to be positive participants in the cosmogenesis of Human-Earth reality rather than the outdated late-Holocene agitation of being fit for capitalist market engagement.

If the Anthropocene serves as a new frame within which to view and construct social modes of presence then we must accept our collective responsibility for our human status as geological drivers of our planet. It is as it is. This is our fate, our lot, what modernity with its striving for rationality, progress, development, wealth, anthropocentrism has bequeathed to us. Most of humanity derived limited benefit from the great turmoils of modernity. The injustice is clear. But we must fashion together a way of inhabiting the Earth as it is. The challenge of changing our energy systems, our food systems, our consumption systems, our transportation systems, and so on are immense. We do so while the vast majority of humanity believe themselves inhabitants of the Holocene. The vast majority of humans act, behave and believe as if the Holocene stability was still holding sway.

We occupy different worlds. The inhabitants of the Ptolemaic cosmos stood eyeball to eyeball with those of the Copernican. Though one held absolute power and dominated symbolic space the other inhabitants were standing on the actual world of orbit and motion. The truth of the Earth is not to be denied. It lies beyond the reach of human symbolisation and ideology.

The great political fault-line is not as the late politics of the Holocene imagine, that is between the economics of austerity versus the economics of Keynesian expansion. Rather it is between the adherents of economic growth (which include both right and left) and those who realise we must move beyond growth, beyond capitalism and its strange alter of State communism. Neither will serve in the Anthopocene. Living in the Anthropocene is living within planetary limits. We are finally recognisably Earthbound. The new human subject is no longer in nature – they are nature. Nature is no longer nature – it is indelibly become humanised. Anthropos is the new agent of geostory. As argued above this does not mean no politics – it just means that politics starts from here.

Final Comments

New thoughts, new perceptions are often strange at first. They seem peculiar, unclear. They don’t fit in with our expectations, our assumptions. The old certainties which formed the background stability of human political and economic life are faltering. Something new is taking place. Our culture, our ideologies, our practices remain centred in a Holocene world that has given way to a new epoch. While there is but one world of course two human modes of inhabiting that world now confront each other. As social theorist Bruno Latour has said: ‘There is indeed a war for the definition and control of the Earth: a war that pits – to be a little dramatic – Humans living in the Holocene against Earthbound living in the Anthropocene’.[6] In one we thought we were above the world, superior to it. In the other, we have stumbled to the recognition that there are necessary limits, that we must inhabit the world within constraints required by the Earth itself.

For those Earthbound in the Anthropocene our fellow humans of the Holocene appear to be inhabitants of a strange, mythical, unreal place. A bizarre parallel world where fossil fuels are developed, where consumption bewitches, where species die. Language itself in the Holocene seems devoid of content. ‘Development’, ‘progress’, ‘sustainability’, the ‘environment’ sound hollow and disconnected, spoken by confused subjects seeking safe purchase in a diminishing fantasia version of the planet. We need a new language, a new way of speaking, a new way of articulating our human-Earth inter-subjectivity. We cannot go back to pre-modern sensibilities for this. That too is a false turn. We are inescapably the beings of modernity. But our sciences, natural and social, need to fashion Anthropocentric resonance. We need deep history, deep sociology, deep economy – that is, frameworks of meaning that situate the human within far wider processes of evolution and life.

Endnotes

[1] The official confirmation of this awaits the 2016 meeting of the Geological Society of London.

[2] See more at: http://globaia.org/portfolio/cartography-of-the-anthropocene

[3] See for example Chakrabarty, R. (2009), The climate of history: four theses. Critical Enquiry 35 (2): 197-222.

[4] McKibben, B. (1989), The End of Nature. New York: Random House.

[5] See, for example, Steffen W. et al (2004), Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet Under Pressure. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag.

[6] Latour, B. (2015), Telling Friends from Foes in the Time of the Anthropocene (pp. 145-155), in Clive Hamiliton et al (eds) The Anthropocene and the Global Environment Crisis – Rethinking Modernity in a New Epoch. London: Routledge.

Featured image: https://theoldspeakjournal.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/0fbee-geologicaltime-scale-bmp.jpg?w=604

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Garavan lectures in social care in the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology. He is the author of Compassionate Activism: An Exploration of Integral Social Care. He is currently chairperson of Feasta's trustees.

|

|Back to Title|

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Supplement 1

Supplement 2

Supplement 3

Supplement 4

Supplement 5

Supplement 6

PelicanWeb Home Page

|