|

Abstract: With the help of planes and solids, this paper presents an enlargement of the field of observation of economic theory. Through this transformation, the distribution of ownership rights to money and wealth assumes a central position in economic analysis. Thus social relevance is returned to economics. The validity of this operation is confirmed by the return of the millenarian field of economic justice to its traditional function as guidance to economic policy. The paper then presents four sets of economic rights and responsibilities that offer the potential of translating principles of economic justice into the complexities of the modern world.

Keywords: economic theory, economic policy, economic practice, economic justice, economic rights and economic responsibilities, social relevance.

Note: Arrows have been added to figures at the suggestion of Dr. Peter J. Bearse.

|

As problems of human and natural ecology mount up, there is growing in mainstream economics the conception of economics for economics sake. The tendency is to see economics as an autonomous discipline isolated from other sciences, and yet dominating all other social sciences. No matter what concerned people within and without the economics profession maintain, the tendency is to neglect those concerns because mainstream economics has an unstoppable inner force of its own that makes it impossible to change course. This paper assumes that this tendency is due not to the will of any individual economist but to the sheer power of their tools of economic analysis. The action is involuntary. The process is mechanical (cf PAER).

The process is not without consequences. Economic theory has lost control of itself. Perhaps no one has made the case stronger than Alan Blinder (1999), who has said: "...too much of what young scholars write these days is 'theoretical drivel, mathematically elegant but not about anything real.'" As a direct consequence, economic theory has become splintered into various schools, which vie for their own preferred policies. Because of the current disarray, monetary policy has largely been left to the bankers; fiscal policy to the politicians; and hardly anyone speaks of labor or land or industrial policy any longer. In a word, by becoming detached from reality, both economic theory and policy risk becoming socially ineffective—which does not mean that economic practices are not causing social consequences of their own.

This paper offers a set of new tools that is capable of changing this course of action. Through these tools social relevance reveals itself as an integral part of the constitution of economic theory, policy, and practice. To be specified at the outset, the new tools do not reject but incorporate the old tools of analysis. Using planes and solids in space, in addition to points and lines, economic theory automatically encompasses a larger social reality and returns to the fold of socially relevant sciences with authority to suggest desirable policies and practices.

While the proposed tools in economic theory are the result of forty years of analysis published in Gorga (1982, 2002), desirable policies and practices are distilled from a program of action presented in Gorga (1959, 1964, 1987, 1991a, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, and 2007). More extensive treatments can be found in the writings of Benjamin Franklin, Henry George, Louis D. Brandeis, and Louis O. Kelso—with their works, necessarily all their works, read in rapid succession and not any of them as a stand-alone effort. Standing alone, these works are open to debilitating objections. Together, they become an impregnable fortress.

TOOLS TO CONTROL ECONOMIC THEORY

Mainstream economic theory is an impressive intellectual construction with its own internal logic. Its structure is a bastion impervious to any external influence; it has become a mathematical science, and as such it is autonomous of any influence that does not enter into its logical structure. The intellectual apparatus of mainstream economic theory, once deconstructed, revolves around the following tool kit, which we propose to preserve and to build upon.

Existing Tool Kit

As everyone knows, economics is built on the theory of supply and demand. The demand of most everything increases as its price decreases; and the supply of everything increases as its price increases. This is the bare structure of most theories in economics, from the theory of growth to the theory of money. To appreciate the full force of this method of analysis one needs to realize that the lines of supply and demand represent sets of numbers—in turn derived from functions of two variables, prices and costs—and then one must see those schedules in movement. As they move up or down, right or left, they meet each other at different points on the Cartesian grid and determine a specific equilibrium of prices and quantities offered and accepted of any item of wealth in the market, from bread to gold.

The basic characteristics of this framework of analysis become evident upon reflection. The focus of attention is on the market exchange; all that goes on before or after the exchange lies outside the purview of the analyst. The mainstream economist qua economist can only analyze, forecast, and report on present or likely future tendencies toward equilibrium of items of wealth that are offered in the market in exchange for other items of wealth, be they currency or pet rocks. The consequences that follow from market exchanges lie mostly outside the purview this framework of analysis. Is the production of items being exchanged in the market causing physical damage, or moral depravation? Is the distribution of ownership rights over items being exchanged causing a concentration of wealth into too few hands? Is the consumption of items being exchanged causing ecological disaster? These are all familiar questions that are at the heart of the economist’s concern. Yet, they can at best be acknowledged by the economist, but they will unavoidably be dismissed as belonging to other fields of analysis such as politics, ecology, morality, and the law, fields that lie outside the expertise and control of the economist.

The analysis becomes more complex daily by the sheer weight of accumulated data; hence equations multiply, econometric applications become more sophisticated, and theorems concerning the characteristics of economic relationships become more and more subtle; indeed, there now seems to be a model for every economic activity—and, lately, for many non-economic activities as well; and if the information is missing or it does not quite fit the case, there is the stand-by option of “as if” assumptions. Impressive as these techniques are, beyond all refinements in the state of the art of mainstream economic analysis, most economists admit to its basic limitations; not only that, they also admit that economic theory has been in a state of crisis at least since the publication of Keynes’ General Theory in 1936. (What did Keynes say is a question that has plagued the profession ever since.) Three of the most recent recognitions of the crisis span the arc from acknowledgment of the limits of mainstream economics (Mankiw 2006) to criticism about the relevance of mainstream economic theory (Manicas 2007) to the belief that economic theory has improved and that it is expected to improve over time (Warsh 2006).

As the history of minor and major theoretical revolutions and counterrevolutions proves, economists are ready to try nearly any stop-gap measure to resolve the crisis—provided the proposed measure does not affect the structure of the theory. This position is non-negotiable; and it is not the purpose of this paper to negotiate it. What is presented for discussion is a far simpler proposition: if we want more comprehensive and more accurate results, we need different tools of analysis. In addition to points and lines, we shall be using planes and solids in space: at first, only rectangles and spheres.

The consequences of this transformation are far-reaching. Rather than attempting to create an improved mainstream theory, we shall incorporate its vital and functioning core into a new framework of analysis which, for a number of consilient reasons, this writer likes to call Concordian economics: as we will see below, the structure makes room for the perspective of each one of the various schools dominating today’s economic analysis; it opens its doors to inputs from various other intellectual disciplines; and it extends itself in a seamless web to cover economic policies and economic practices.

New Tools in Economic Theory

Through laborious logico-mathematical steps (Gorga 2002: 41-158), one obtains a restructure of mainstream economic theory (Gorga 1982) and its gradual transformation into Concordian economics. While the book presents a description of that transformation with its resultant new mathematical models (Gorga 2002: 25, 38, 71, 74-6, 121-25, 129-37, 153-58, 168-70, 264, 303-20), the present paper reproduces the core of that ground with primary assistance from geometry; thereafter, it extends the analysis to cover economic policy as well as economic practices for implementation of selected economic policies.

The key results of Concordian economic analysis are these. In order to eliminate a set of innate logical contradictions at the very foundation of economic analysis, the nexus between saving and investment is broken and it is replaced by the complementary relation between Investment defined as all productive wealth and Saving defined as all nonproductive wealth—a term that is better replaced with Hoarding.1 The analysis starts anew on the basis of the proposition that Investment is Income minus Hoarding. Furthermore, since money and financial instruments are not wealth, but only represent wealth, in macro, as distinguished from microeconomics, one cannot add money to real wealth.2 The two entities have to be kept separate. And then the question arises: What is the relationship between the two?

From Aristotle to the Doctors of the Church there was no doubt as to the answer to this question. During this long stretch of time, much economic analysis was built on the equivalence of money and goods in the exchange. It was the distinction between the two and their linkage in the relation of equivalence that provided the objective base for the determination of conditions of justice in the exchange of wealth. If we accept this answer, to satisfy well-known requirements of the principle of equivalence, we search for a third element to link monetary and real wealth together and we find it in the set of rules and regulations that in every society governs the distribution of ownership rights over real and monetary wealth—and we do not stray away from pure economic theory, because we are presented with the monetary value of those rights. The following diagram (Gorga 2002: 36, 163, 314) incorporates these results; it represents the integration of these values on one plane, in this fashion:

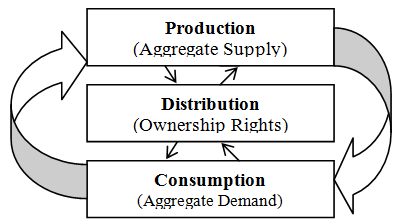

Figure 1. The Economic Process

In this figure, the values of “production”, namely the values of all real wealth produced over a specified unit of time are assembled into one category of thought that is recognized as aggregate supply. (It is to be noticed that this unit is “pure” because it contains only stocks of real wealth and no monetary wealth. It is also to be noted that in a more complete treatment this value ought to be observed from the point of view of demand as well as supply: thus we ought to have an analysis of the demand and supply of the production of all real wealth.) We follow the same procedure for the values of monetary wealth, thus firmly separating real wealth from monetary wealth, and we call the result “consumption” or aggregate demand. (Ditto for the treatment of all monetary values, which here are not observed from the point of view of supply: The question of the quantity of monetary values created lies outside the scope of this presentation.) We finally repeat the procedure for the aggregate values of ownership rights over real and monetary wealth, and we call the result “distribution” of ownership rights. (At this juncture we assume that the values of ownership rights over real wealth are identical to the values over monetary wealth). In sum, we have enlarged our field of observation from points and lines to planes and interactions among planes; and, rather than leaving the question of the interaction between demand and supply open (cf. Klein 1970: 143), we have continuously specified—and distinguished one from the other—the demand and supply of (a) real goods, (b) monetary instruments, and (c) values of ownership rights over real and monetary wealth.

Figure 1 reads as follows. When real goods and services pass from producers to consumers, monetary instruments of a corresponding value pass from consumers to producers. Then one cycle of the economic process is completed—and it is accompanied by the silent exchange of values of ownership rights over monetary and real wealth. Both money and goods change hands. The unit of account can be the economy of one person, one nation, or the world. In macroeconomics, the exchange occurs neither between two insignificant commodities (cf. Schumpeter 1936) as in microeconomics nor between any two forms of financial instruments as in the economics of Wall Street. In macroeconomics, fully respecting the laws of supply and demand the total production of real wealth is exchanged for the total availability of financial resources—as in Keynes’ principle of effective demand (see Brady 1996). Finally, in this figure the exchange visibly occurs under a regimen of social and legal relationships: ownership is apportioned at the moment of creation of wealth; and only owners can legally exchange wealth.

An effective way to analyze the instantaneous relationships captured by Figure 1 is to reduce it all to the economics of only one person. A person who snaps the apple from a tree, vs. gathering seeds, for instance, while respecting as always the rules of supply and demand commits an act of production. This person automatically apportions the ownership of the apple to the self, which means that this person is legally empowered, as it were, to sell the apple to the self. Thereafter, this person is free to eat the apple—or sell it to others. One of the merits of Figure 1 is that it describes the economic process as a whole. Everything is instantaneously related to everything else. Thus we run away from the shattered world of the schools and go back to the world of Classical economists who knew that economics is composed of the integration of Production, Distribution, and Consumption of wealth. This integration can be made more specific by a more extensive and updated reading of the terms, along these lines: The Theory of Production—namely a pure and robust production function—is concerned with the production of real goods and services (as might be studied by Supply-Side economists); the Theory of Distribution is concerned with the distribution of the value of ownership rights over real and monetary wealth (as might be studied by Institutionalists); and the Theory of Consumption is concerned with the consumption—or expenditure—of monetary, i.e., financial instruments (as might be studied by Demand-Side economists). More importantly, by recognizing that Figure 1 is the flat image of a sphere we bring the mathematics and geometry of economics up to the standards that prevail among modern engineers and scientists (see, e.g., Thompson 1986: 36), namely:

Synthetic Model of the Economic System as a Whole

(from Gorga 1991b)

p* = fp(p,d,c)

d* = fd(p,d,c)

c* = fc(p,d,c)

where

p* stands for rate of change in total production

d* for rate of change in the values of distribution of ownership rights

c* for rate of change in total expenditure.

And, most important for our immediate purposes, we can see that the theory of distribution of income and wealth now occupies a very central position in economics. All that relates to the distribution of ownership of income and wealth becomes an immediate and integral concern of economic theory—no longer an afterthought or an issue placed at the margins of economic science. Related issues of social relevance of economics can no longer be shunned aside by the economist on the assumption that they are external to economic theory. These are indeed issues that lie at the very core of economic theory; and one does not stray away from mathematical and quantifiable theory either. What is to be measured and evaluated is the economic value of ownership rights over income and wealth—and the different economic effects of different patterns of distribution of income and wealth. Decisions relative to these issues are taken during the very process of production and exchange of wealth; they are not something to be concerned with only after the more impellent problems of production and exchange are resolved, as assumed in Keynesian economics and, mutatis mutandis, in mainstream economics, see, e.g., Klein ([1947] 1968: 187). The concern about the social relevance of economics—as all Institutionalists have devoutly wished—is now brought within the purview of the economist.

Issues of distribution of economic values of income and wealth are not givens; they lie at the very core of the economic process and are determined by the inner workings of this process. On Mars the situation might be different; on earth, people create not only real or physical wealth—they also assign values to this wealth. Indeed, it is economists (and accountants) who, assisted by the laws of supply and demand, assign these values as best they can. Lawyers only validate these statements by transforming them in negotiable legal instruments that are called ownership rights. These rights might belong to an individual person, to a corporation, or to the state; but they legally belong to someone. And an exchange of real wealth for monetary wealth involves at the same time an exchange of the value of ownership rights over real and monetary wealth. It is thus that, no matter the disclaimer by many economists, economic values are created and are created at the very core of the economic process.

TOOLS TO CONTROL ECONOMIC POLICY

Having discovered that the distribution of ownership rights over income and wealth is an integral part of economic theory, the question becomes: What are the tools to obtain the desired pattern of distribution of income and wealth? This is the eminent question of economic policy. Economic theory tells us that, once this pattern is set, most other questions of economic policy are automatically settled. The answer to the question is well known.

Existing Tool Kit

Even though the historic roots of economics lie in moral philosophy, economists have lately assumed that they have nothing to contribute to the discussion concerning the selection of patterns of distribution of income and wealth. They have left the field to lawyers, ethicists, philosophers, sociologists, and political scientists. Mainstream economists believe that they do not have—and, what is more important, they ought not to have—any tools to control the pattern of distribution of income and wealth. Mainstream economists assume that this is a given, namely a determination that is and ought to be left to society as a whole. Economics, as pure science, as an autonomous mathematical science, is supposed to analyze the effects of various societal decisions, but not to intervene in those decisions. It is a direct consequence of this assumption that economic theory is fast becoming socially irrelevant.

Under these conditions, the discussion on economic policy falls into a trap. The discussion becomes the property of various schools of economics, each purporting the benefits of its own dictates and none being able to convince the other schools of the validity of its positions.

We do not need to put a step on this slippery slope. Once it is established that the pattern of distribution of income and wealth is an integral part of economic theory, the analysis is restricted to this question: How can we translate economic theory into economic policy? In the paragraphs below we will offer a set of new/old tools for consideration. This set calls for the construction of the theory of economic justice, and therefore economists will discover that they have much to contribute to it. This is the high road to re-establish social relevance to economics.

Proposed Tools to Control Economic Policy

A mere glance at the history of economic thought makes us glean this proposition: The transmission belt that for millennia carried economic theory into economic policy is the doctrine of economic justice. While remaining astonishingly constant from Aristotle to the Doctors of the Church (see, e.g., Wood 2002: 83), this understanding allowed for continuous adaptations to the circumstances of the moment. The doctrine of economic justice was divided into two planks: distributive and commutative justice. Distributive justice guided rules and regulations that govern the division of wealth as it is created; commutative justice guided rules and regulations that govern the transferal of wealth between buyers and sellers at the moment of the exchange. While the Doctors of the Church left much room for discretion in the determination of distributive justice to the parties involved in the economic process, they reached a firm and revolutionary conclusion about the dictates of commutative justice. The commutation of wealth, namely the exchange, occurs in accordance with principles of justice, they discovered, only if it reflects a free market price: a price determined in a market that is not dominated by either governmental or private monopolistic forces (see, e.g., Schumpeter 1954: 98-99).

While this formula appears simple, it envelops great complexities. With it, the Doctors of the Church unified the social requirements of freedom with those of morality in economics; and it was the exercise of morality that yielded freedom. The application of this formula created the essential conditions for the enterprise system to be as free as it could be at the time.

Over time, this ordered set of priorities was twisted around and its power dissolved. Through insistence on unfettered economic freedom, the unity of freedom and morality—with its inherent social relevance—was shattered and the doctrine of economic justice was lost in the fog of time.

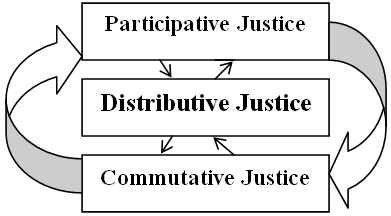

Truth to tell, the dissolution of the doctrine of economic justice was facilitated by the fact that it was never presented with a visible head. People with direct or indirect access to land and natural resources participated in the economic process as a matter of fact through well-established privileges and as a consequence of unspoken sets of rights (indirectly, access to land and natural resources was secured through the commons: for millennia the safety valve to preserve the dignity of the poor). Hence, it never occurred to Aristotle or any of the Doctors of the Church to make explicit the requirements of a third plank that might be called participative justice (Gorga 1999, 2007). For a great variety of reasons, those conditions are no longer in existence. Today, one has to beg in order to participate in the economic process. And if one does not take part in it, one is marginalized; one is shunted to the margins of society. Hence the plank of participative justice, as it is increasingly recognized from many quarters, must be explicitly formulated. When participative justice is added to the other two planks, the doctrine is completed and transformed into the theory of economic justice. Once that is done, one is presented with a framework of analysis that can be represented in this fashion:

Figure 2. Economic Justice

Figure 2 reads as follows. Participation in the economic process is a matter of justice, because only men and women who participate in the production of wealth are entitled to the distribution of ownership of a share of the wealth created through their participation.3 A just commutation of wealth, a just exchange, is implicit in the very distribution of wealth in accordance with one’s participation; but, of course, the principle of commutative justice extends itself to cover the exchange of wealth just created for other wealth existing on the market. It is in accordance with these objective principles that the pattern of distribution of current income and wealth is and ought to be determined. Economists can render these calculations very precise.

But economists have much broader tasks than these. Figure 2 is a mirror image of Figure 1. If the distribution of ownership rights is an inherent part of the economic process, as we have seen in the previous section, economic justice becomes a natural extension of economic theory. Indeed, one can just as soon separate economic theory from economic justice as one can separate a person from her shadow. (The forced separation of these two entities has ineluctable consequences of its own that ought to be of great interest to the investigative powers of the economist.) Given this condition, a minimum set of questions to be asked by economists in the formulation and evaluation of any economic policy might be: Does the proposed policy favor participation in the creation of wealth? Does it allow for a fair distribution of the wealth thus created? Does it allow for a fair transfer of wealth from one person or group to another? Much could be said on these issues, but since much is already well known, we shall shun away from broad and elaborate discussions of these issues.

The wisdom of staying away from broad and elaborate discussions, however, does not necessarily require staying away from the specifics of the case. The specific question is: How can we transfer the principles of economic justice into the complexities of the modern economy?

Needless to say, this is a question that is not formally and comprehensively raised in mainstream theory. This is a question that arises naturally and forcefully within the context of the structure of Concordian economics.

TOOLS TO CONTROL ECONOMIC PRACTICES

In the section on economic theory we have seen how does the economic system create wealth, how its value is determined by economists and accountants, and how its value is then transformed in ownership rights by lawyers. In the section on economic policy we have observed how economic justice determines the apportionment of those ownership rights. In this section we shall observe how the economic system operates in practice.

Lack of an Existing Tool Kit

“High” mainstream theory is silent on the practices of economics. This neglect is not due to chance; rather, it is due to the assumption that, since economic practices are determined by society at large and are supposedly controlled by allied social disciplines, they lie outside the economist’s field of expertise. Indeed, having abandoned the field to lawyers, and ethicists, and philosophers, and sociologists, and political scientists, mainstream economists have become passive takers of a proposition that lies at the very core of the issue. This is the proposition that present ownership rights provide practical rules for the distribution of future ownership rights. The proposition has long legs, because it determines the pattern of future distribution of income and wealth. Economists observe every day the manifold negative consequences of this belief, but feel powerless to even address the issues. This is another juncture at which, by taking themselves out of the discussion, economists are threatening to make economics a socially irrelevant discipline.

To regain their power, economists have only to look at it as an economic, rather than a legal, political, or moral issue. If they do that, they discover that their assumptions are faulty. The error is elementary. The reasoning is circular. In order to enter and to break this circular form of argumentation, namely that present property rights determine future property rights, economists need to remember that property rights are pieces of paper: a piece of paper does not—and cannot—create real wealth. It is not even the exercise of property rights that creates real wealth. Property rights are a bundle of rights that link human beings to things. Their current owners may wish as hard as they can, it is not in the nature of property rights to create wealth.

It is not the use of property rights, but the use of property—namely, the use of real goods and services—that creates new wealth. The distinction is fundamental. The discussion is shifted away from the abstract legal field on to a concrete field. The discussion is focused on the observation of the economic reality. The use of real goods and services to create new wealth is infused, not by property rights, but by the exercise of economic power. To an economic power corresponds an economic right. As specified below, temporally, logically, economically, and legally, economic rights precede property rights. Economic rights are the generators, the fathers and the mothers, of property rights. The nature of economic rights becomes clear when the two rights, economic rights and property rights, are observed as separate and distinct entities, and then both rights are placed in contraposition with entitlements. The three terms are often used as synonyms. They are not. As specified in Gorga (1999),

First, the content of these three entities is different. The object of property rights are marketable things, tangible or intangible things such as material goods and services. The object of entitlements are human needs, from food to shelter to health. The object of economic rights are economic needs. Second, the legal form of these three entities is different. Property rights are concrete legal titles over existing wealth; economic rights are abstract legal claims over future wealth; and entitlements are moral claims on wealth that legally belong to others. Finally, the quantity that they measure is variable. While both property rights and entitlements relate to existing wealth, and therefore a necessarily finite quantity, economic rights relate to future wealth, an unknown and elastic—if not a potentially infinite—quantity.

|

Economically, and consequently legally, real wealth is created by the exercise of economic rights—indeed, economic rights and economic responsibilities, as we shall see. Hence economists are fully entitled to extend their competence to the field of economic rights and economic responsibilities. Economists will discover that the field is wholly within their range of expertise and responsibility. At the end of this journey, economists shall be able to offer to lawyers, ethicists, and philosophers, as well as political scientists and politicians, this proposition: Future ownership rights are determined, not by property rights, but by economic rights—indeed, they are determined by economic rights and economic responsibilities. Thus the closed circuit that at present imprisons economic theory, the proposition that property rights beget property rights, is broken. Economists are in charge of economic issues.

New Tools to Control Economic Practices

The transmission belt that carries principles of economic justice into the complexity of modern economic life, and shapes objective guidelines for the formulation and evaluation of just economic policies is the presence of economic rights and economic responsibilities (ERs&ERs), both lodged in the same person at the same time. These two conditions need to be clarified. Economic rights and responsibilities need to be lodged into the same person, otherwise one does not follow an economic discourse in which everything is strictly related to everything else; rather, one follows escapism: if my father, my uncle, or the state is responsible for my welfare, we are lost, as Keynes used to say, “in a haze where nothing is clear and everything is possible” (Keynes 1936: 292). The second condition is equally important. Economic rights are rooted, not in abstract morality, but in our own concrete economic responsibilities (cf. Gorga 1999).

ERs&ERs come forward in response to the well-known requirements of the factors of production identified by Classical economists as land, capital, and labor—with the addition of a modern distinction between financial and physical capital. Guided by these economic needs, our focus of attention is on the satisfaction of the plank of participative justice; successive iterations that are mostly skipped in this presentation would reveal that the same rights and responsibilities satisfy also the requirements of the planks of distributive justice and commutative justice. A minimal set of economic rights and corresponding responsibilities is as follows:

1. We all have the right of access to land and natural resources. This is a natural right. It belongs to us just in virtue of our humanness. Land and natural resources are our original commons. They belong to us all. This is an essential right, because without the possibility of exercising it, we are deprived of the possibility of participating in the economic process. And without this participation, we are marginalized; we are made dependent on the good will of others. The most direct way of securing this right in the complexity of the modern world is neither through squatting nor through expropriation; rather, it is through the exercise of the responsibility to pay taxes for the exclusive use of those resources that are under our command—with a corresponding reduction of taxes on buildings and man-made improvements on the land. The exercise of the responsibility to pay taxes on land has a double function: It secures our right to the use of the resources that are under our command and it also makes room for others to access land and natural resources that they need. Land taxation is the economic bridge between hoarding, namely the accumulation of idle land, and the right of access to that land with its natural resources. Paying taxes on the value of land and natural resources gradually encourages dis-hoarding, hence it lowers the price of the land, and correspondingly opens up the resources of that land to all those who need them and can make use of them. Worrisome hoarding is especially that which occurs both downtown and in the belt surrounding major cities and towns. It is to leapfrog over this belt that people go to the suburbs in search for affordable land, thus creating overstretched lines of communication and protection and overlong commuting lines—with consequent waste of fuel that overtaxes nonrenewable resources, the ozone layer, the pocketbook, and the nervous system. Paying taxes on land value is a most fair form of taxation, because it implies returning to the community part of the value that is created, not by the individual owner, but by the community. Land that sits idle does not produce income, true; yet, it produces capital appreciation over time: Rare is the case of capital loss; and even when that occurs, the relative loss tends to be smaller than the loss on other assets. (To see how this pair of ERs&ERs meets also the requirements of distributive and commutative justice, let us simply consider that, if one avoids taxes, the total tax load is not going to be distributed fairly among the population. And if one avoids taxes, one obtains something—i.e., private control over a quantity of resources—for which one does not offer proportionate compensation to the rest of the community.)

2. We all have the right of access to national credit. Since national credit is the power of a nation to create money, and since the value of money is given by the value of wealth left over by past generations and the creativity of every person in a nation, national credit is the last frontier, the last commons. Without access to credit today one is made economically impotent. Worse, since this advantage is granted to the privileged few, it is automatically denied to the majority of the population who are henceforth condemned to pay a higher rate of interest, if they obtain credit at all. Of course, such a loan should be extended only on the basis of the responsibility to repay the loan. And these loans will have a high chance of being repaid because they ought to be issued at cost and issued exclusively to individually owned enterprises, Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs), and cooperatives, as well as states and municipalities, and issued exclusively for capital formation, namely for the creation of new wealth—not to buy financial paper, consumer goods or goods to be hoarded or to cover administrative expenses of states and municipalities. Capital credit liberates people, while consumer credit enslaves them.

3. We all have the right to the fruits of our labor. This right should not be limited to the right to obtain only a wage. It should be extended to cover the other major fruit of economic growth over time: capital appreciation—as well as being subject to capital loss, of course. The only justification for reserving capital appreciation for stockholders, the owners of a corporation, and excluding workers from it, can be found in the fact that loans are given only to owners of past wealth (the Catch-22 of today’s economic reasoning: “save and invest and you too can become rich”—as if this proposition were either economically feasible or ecologically sustainable.) But from now on this right can be extended to people who do not have prior wealth through the right of access to national credit—especially by legally transforming workers into owners through individually owned enterprises, Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs), and cooperatives. Of course, this full right should be extended only in correspondence with the responsibility to offer services of value equivalent to projected compensation. And there will be an outpouring of such services because, while in a command and control economy workers are requested to check their brain at the factory gates, in a socially responsible economy—an economy in which rights are exercised on the basis of responsibilities—workers/owners are legally, socially, and psychologically empowered to exercise their brain fully at their work post.

4. We all have the right to protect our wealth. This right seems to be universally accepted, except in one case that matters most: in the case of the trustification process, the process used especially after the Civil War in the United States to create corporate trusts and repeated in a hundred subtle variations ever since. (People feel free, not only to acquire shares of the stock of one corporation, but free to use that stock to acquire another whole corporation by all forms of trusts, mergers, and acquisition. The very idea of the corporation, forever a public entity, has thus been privatized and monetized.) There are two ways in which corporations grow: One is through internal growth, and this approach ought to be protected in no uncertain terms; the other is through external purchase and, with limits, this manifestation ought to be prohibited in no uncertain terms. Why? Because this prohibition is the only certain way to protect the wealth of present owners. And if it is assumed that most stockholders of the modern corporation are happy to have their shares bought and sold on the market, it must be granted that growth-by-purchase takes wealth away from workers who have contributed to create that value—and many times, in the trustification process, lose their work site as well. All in the name of efficiency—a misnomer that stands for private financial gain generated at the expense of shifting costs onto the shoulders of the community at large. Of course, this right ought to be purchased only at the cost of the responsibility to respect the wealth of others. These are two-way streets. We cannot even attempt to restrain the Pac-Man economy, while we use Pac-Man instruments.

These economic rights and responsibilities can be exercised by anyone who does not only want to receive economic justice, but also wants to grant economic justice to others. Indeed, these are the essential conditions for the establishment of economic justice, as well as the establishment of a free enterprise system, in the modern world. As a consequence of the dynamics of the implementation of these four marginal changes in our current practices, economic freedom will be expanded to embrace all who want to subject themselves to the rigors of the economic process—and then the few remaining hard cases can be easily taken care of by charity. No. There is no compulsion in any of the above suggestions. The landowner can pay more taxes and control more land or can escape the tax levy altogether by reducing land ownership to zero; the applicant for a national loan can escape the constraints suggested for access to national credit by tapping into private capital markets; the worker can escape the responsibilities of ownership by vying for a job rather than an equity position; and the owner of physical capital can escape the constraints implicit in the proposed anti-trust policy by remaining below the trigger of an agreed-upon threshold for growth-by-purchase prohibition. This prohibition should apply to the largest corporations first and be gradually expanded to include eventually all except, let us say, corporations engaged in intrastate or regional commerce.

Intellectually, the proposed economic rights and economic responsibilities perform functions outlined in the conception of “general abstract rules” by Hayek (1960: 153), the “original position” by Rawls (1971: 12, 72, 136, 538), the “reverse theory” by Nozick (1974: 238), and the “Principle of Generic Consistency” by Gewirth (1985: 19); practically, they will function as Gladwell’s (2000) “tipping points”. Ultimately, it was a poet, Vincent Ferrini (2002), who caught the essence of economic rights and economic responsibilities by identifying their ability to provide “the answers to universal poverty and the anxieties of the affluent.”

Operating as tipping points in our modus vivendi, ERs&ERs will set in motion a process of interdependence that respects the reality of economic affairs, and the reality of human relationships. Recognizing that most people and most businesses always act morally, the increasing number of “bad apples” that at times seem to receive all the attention (and envious support) of a superficial intellectual world will be recognized as dangerous exceptions, perhaps ostracized, but certainly no longer applauded. Once the tendencies of these people are kept in check, all wealth will be distributed, not equally—that is meaningless utopianism—but fairly. The assurance for this result resides in the transformation of the current social contract into a legal contract: when landowners pay their share of land taxes, they will sell their hoards and access to land and natural resources will automatically be opened up for most people; when people will get access to national credit, many will become independent entrepreneurs; when workers are transformed into owners, they will have the legal tools to demand a fair distribution of income; when growth-by-purchase will mostly become a forbidden activity, most corporations and most employee/owners will preserve their independence. These measures, by consistently curbing the excesses of the few for a period of at least ten years, will cumulatively lead to a fair distribution of income and wealth. To reassure ourselves of this outcome, let us comprehensively look at the issues from another point of view. If land owners were to use their possessions of land and natural resources efficiently (with efficiency measured through lower private capitalization and higher effective demand), would there be such wanting in the world? If national credit were made available to all entrepreneurs at cost, would we not translate the immanent reservoir of creative powers into economically profitable ventures? If workers were transformed into worker/owners, would we not increase our extant productive capacity incommensurably? If corporate growth-by-purchase—with accompanying translation of that economic power into corruption of our political system—were curbed, would we not obtain less concentration of economic power into a few hands?

All four ERs&ERs naturally lead to a fairer distribution of income than prevails today. Eventually, with a fair distribution of income and wealth, there will no longer be any need for redistributive programs, which are an expression of double utopianism (first, people as if living in la-la land are allowed to accumulate much, no matter how; and then they are expected to peacefully discharge their ill-gotten wealth). Preserving their current wealth, the rich will grow richer at a steady but slower pace; and the poor will no longer be poor, because they will have all they need. Lacking fuel at both ends, violent oscillations in the business cycle will be abated.

We will thus recover the essential truth of economics. This is the truth that there are two conditions of growth: economic freedom and economic justice, as concrete expressions of freedom and morality. Both are essential. The relationship between the two is quite clear: While freedom does not necessarily bring justice with it, justice unavoidably brings freedom. One can abuse freedom by denying freedom to others, one can never abuse justice. Hence, the initial condition of freedom for all is proof positive of the existence of economic justice in the land. This is economics that is socially relevant. And the relevance is not an afterthought. The relevance is implicit. The social import of economic theory is realized when the distribution of ownership rights is seen as an integral part of its constitution; and the social import of economic justice and economic rights and responsibilities is simply stated: We must prevent all foreseeable injustices from occurring. Once an injustice has occurred, there is nothing that can be done to undo the dastard deed. This is the bosom of realism.

One last question: Is the proposed program of action the latest expression of utopianism? The curt answer is: No. Utopianism has consistently been based on the wishful thinking of a single person. The proposed program of action results from filling in the gaps of a millenarian train of thought that, in a seamless web, extends itself at least from morality to economic theory and from there—through economic justice—to economic policy and practice. Utopianism promises immediate results, as if by magic. This proposed program of action asks for concerted, protracted effort. Whatever life Utopianism has, it is based on the fanatical following of a small group of people who try to force it upon the will of the multitudes. The proposed program of action is expected to be readily understood and spontaneously implemented by the multitudes.

CONCLUSION

The lament that economics lacks social relevance assumes many forms, but these are mostly centered on the treatment of issues of distribution of income and wealth. We have found that these issues are not even investigated by economists today because they assume that they lie beyond the field of economics. Hence, by placing this issue at the very core of economics, we have given back social relevance first to economic theory, then to economic policy, and finally to economic practices. Without ever abandoning the field of economics, we have established a continuity of discourse between three stepping stones in economic analysis. We have followed this line of reasoning. Since money and financial instruments are not wealth, but only represent wealth, in macroeconomics one cannot add money to real wealth. The two have to be kept separate. This condition raises the question about the relation between money and real wealth. As in the economics tradition from Aristotle to the Doctors of the Church, we have recognized that money and real wealth must be equivalent in value. But equivalence is a formal relation among three terms. What is the third term? The third term that links money to real wealth is the economic value of ownership rights; hence, we have presented a restructure of economic theory that reflects the need to study not only the monetary economy but also the real and the legal economy at the same time. From this new framework of analysis, novel answers are given to the question: How is the distribution of ownership rights achieved today, and how “should” it be achieved? An investigation of the economic, rather than the legal, moral, or philosophical aspects of this question leads to the transformation of an age-old doctrine into the theory of economic justice and to the discovery that the creation of wealth is achieved, not through the exercise of property rights, which are static, but through the exercise of well-defined economic rights and economic responsibilities, which take care of the dynamic needs of the economic world.

FOOTNOTES

1. Every step of the way in Concordian economics, decisions are taken following relentlessly the dictates of fundamental rules of logic. For instance, analysis reveals that since current definitions of saving and investment contain items that are productive (farmed land) and items that are nonproductive (fallow land) of further wealth, both saving and investment respect neither the principle of identity nor the principle of non-contradiction and therefore they cannot be equivalent to each other, as they ought to be for their relation of equality to be formally valid (see, e.g., Allen 1970: 748).

2. The separation of real wealth from monetary wealth is an integral part of the transformation of Keynes’ model into the series of mathematical models that provide structure to Concordian economics. This is a procedure that, outlined with the help of geometry (Gorga 2002: 32-37), starts with the enlargement of the definition of consumption from expenditure on consumer goods to spending in all its manifestations (ibid., 139-50), passes through the definition of money (ibid., 222) and the monetary formulation of the Flows Model (ibid., 309-12), and ends with the establishment of the equivalence of the processes of production, distribution, and consumption (ibid., 312-19). The description of these three processes and the economic process as a whole form the substance of Concordian economic theory (ibid., 159-234).

3. What to do with the widow, the orphan, and the handicapped is a moral issue. Economics does not do anything for them. Indeed, as proved by the history of the world, even in the richest of the communities at the height of the business cycle, economics cannot do anything for them. Their number can become so overwhelming, their needs so vast, that even charity becomes powerless. Economics cannot do anything for the widow, the orphan, and the handicapped—unless, of course, they own stocks and bonds. But then they are not poor; they do not need any assistance through morality. They are capitalists and by the virtue of being capitalists, by the virtue of owning the machines, they participate—through remote control of the machines—by right in the economic process.

Acknowledgments: This paper is uniquely due to several maieutic interventions, truly beyond the call of duty, by Dr. Wilfred Dolfsma. I also would like to acknowledge a clarification brought to this paper by Godfrey Dunkley. If this paper has become a cogent presentation less exposed to potential debilitating criticism of single points, it is due to innumerable constructive suggestions by two referees of Forum. A more detailed background for this paper is contained in “The Economics of Jubilation”, an unpublished monograph that has been well received by such a diverse audience as Dr. Michael E. Brady, Dr. John C. Rao, Professor William J. Baumol, and Professor Roger H. Gordon. That work, in turn, is based on a framework of analysis which was greatly assisted for 27 years by Professor Franco Modigliani and 21 years by Professor Meyer L. Burstein, among others.

REFERENCES

Allen, R. G. D. (1970) Mathematical Economics, 2nd ed., London and New York: Macmillan, St. Martin’s.

Blinder, A. (1999) Quoted in "Students Seek Some Reality Amid the Math Of Economics," by Michael M. Weinstein, The New York Times, September 18, 1999, pp. A17, A19.

Brady, M.E. (1996) “A Comparison—Contrast of J.M. Keynes’ Mathematical Modeling Approach in The General Theory with some of his General Theory interpreters, especially J.E. Meade”, History of Economics Review (25): 129-158.

Fanfani, A. (2003) Catholicism, Protestantism, and Capitalism, Norfolk, VA: IHS Press.

Ferrini, V. (2002) “Gorga worthy of note”, Gloucester Daily Times. December 11, A6.

Gewirth, A. (1985) "Economic Justice: Concepts and Criteria," in K. Kipnis and D. T. Meyers, (eds.) Economic Justice: Private Rights and Public Responsibilities, Totowa, N.J.: Rowman & Allanheld.

Gladwell, M. (2000) The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, NY: Little, Brown & Company.

Gorga, C. (1959) A Synthesis of the Political Thought of Louis D. Brandeis. Graduation Dissertation University of Naples.

Gorga, C. (1964) "Not Simply a National Fund, but a Stabilization and Development Fund”, Mondo Economico 19(14): 14-16.

Gorga, C. (1982) “The Revised Keynes' Model” (an Abstract), Atlantic Economic Journal 10(3): 52.

Gorga, C. and Kurland, N. G. (1987) “The Productivity Standard: A True Golden Standard,” in Every Worker An Owner: A Revolutionary Free Enterprise Challenge to Marxism, D. M. Kurland (ed.) Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Social Justice.

Gorga, C. (1991a) “The Dynamics of the Economic System,” unpub. man.

Gorga, C. (1991b) "Bold New Directions in Politics and Economics," The Human Economy Newsletter, 12(1): 3-6, 12.

Gorga, C. 1994. "Four Economic Rights: Social Renewal Through Economic Justice for All,” Social Justice Rev. 85(1-2): 3-6.

Gorga, C. and Weeks, S. B. (1997) “Fisheries Renewal: A Renewal of the Soul of Business,” Catholic Social Science Rev. 2: 145-161.

Gorga, C. (1999) "Toward the Definition of Economic Rights,” Journal of Markets and Morality, 2(1): 88-101.

Gorga, C. (2002) The Economic Process: An Instantaneous Non-Newtonian Picture, Lanham, MD. and Oxford: University Press of America.

Gorga, C. (2007) “Economic Justice,” in Catholic Social Thought, Social Science, and Social Policy: An Encyclopedia, Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1960) The Constitution of Liberty, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Keynes, J. M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, NY: Harcourt.

Klein, L. R. (1968 [1947]) The Keynesian Revolution, 2nd ed. New York: Macmillan 1968.

Klein, L. R. (1970) “The Use of Econometric Models as a Guide to Economic Policy,” in Selected Readings in Econometrics. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

Manicas, P. T. (2007) “Endogenous Growth Theory: The Most Recent ‘Revolution’ in Economics,” Post-autistic Economics Review 41:39-53.

Mankiw, N. G. (2006) “The Macroeconomist as Scientist and Engineer,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20:29-46.

Nozick, R. (1974) Anarchy, State, and Utopia, NY: Basic Books.

Rawls, J. (1971) A Theory of Justice, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1936) "The general theory of employment, interest and money," Journal of American Statistical Association (31): 791-95.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1954) History of Economic Analysis, NY: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, J. M. T. (1986) Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos, Geometric Methods for Engineers and Scientists, New York: Wiley.

Warsh, D. (2006) Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery, New York: Norton.

Wood, D. (2002) Medieval Economic Thought, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

POSTCRIPT

It might be appropriate to devote a few ending paragraphs to list some of the effects that can expected to flow from Concordian economics. Concordian economics allows us to

- see what happens inside the box, at the very core of the economic process

- reduce immeasurably the level of abstraction in economics

- unify economic theory by not recognizing the distinction between micro and macro economics

- see everything related to everything else—internally as well as externally

- money as an entity in itself separate from real wealth

- money as an integral part of the economic system

- place justice at the very heart of the economic process

- reconnect with the millenarian tradition of economic justice

- and thus provides a rudder to the difficult decisions of economic policy

- determine whether a suggested policy increases participation in the economic process; favors an equitable distribution of economic rewards; and whether the exchanges are fair and equitable

- see hoarding, such an important element of economic life

- and to incorporate hoarding in the full structure of economic theory

- create a concerted set of economic rights and responsibilities

- as a safe guidance to practical decisions of daily life

And if the right of access to national credit (see, www.thepetitionsite.com/325/007/323/a-patriotic-reform-of-the-fed/) is exercised by the people at a noticeable degree, these other benefits can also be expected to be achieved in due course:

- The monetary system is placed on a stable and just base

- The market will be allowed to function as it is intended to do

- Too-big-to-fail ventures will be allowed to fail—if they fail

- The taxpayer will no longer be pressed to bear the cost of market failures

- From at best 5% Capitalism, we will gradually be able to create 100% Capitalism.

Since Concordian economic rights are rooted in responsibilities, they are indeed rights—not privileges. They are unalienable universal rights available to one and all in society. They are essential to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Only civilized people, people truly integrated within themselves and within society can give and receive economic justice. Justice is a virtue. To give and receive economic justice requires love, the highest of theological virtues.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Carmine Gorga is a former Fulbright scholar and the recipient of a Council of Europe Scholarship for his dissertation on “The Political Thought of Louis D. Brandeis.” Dr. Gorga has transformed the linear world of economic theory into a relational discipline in which everything is related to everything else—internally as well as externally. He was assisted in this endeavor by many people, notably for twenty-seven years by Professor Franco Modigliani, a Nobel laureate in economics from MIT. The resulting work, The Economic Process: An Instantaneous Non-Newtonian Picture, was published in 2002. During the last few years, Mr. Gorga has concentrated his attention on the requirements for the unification of economic theory and policy. For details, see www.carmine-gorga.us.

|