W Steffen, P Crutzen, J McNeill, photos by M Klum

|

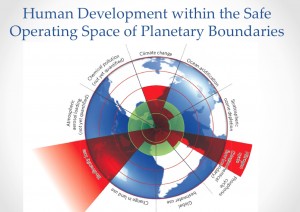

This is what we humans face as the huge challenge for our common future: If we keep Earth within the safe operating space of planetary boundaries, and we work with and integrate within the boundaries of its landscapes, humanity and the world can thrive. But if we transgress these scientifically drawn boundaries, we will put ourselves in a danger zone, where even minor actions can trigger catastrophic outcomes.

The scientists Will Steffen, Paul J Crutzen, and John R McNeill share the dimensions of this challenge of the Anthropocene, illustrating to us that we are now “in the physics of a 3-6-9 world.” Number 3 is because of climate change and the Earth is moving towards a global temperature of 3 degrees Celsius, a global warming that the planet never experienced over the last 25 million years. Number 6 is because we are in the midst of the 6th mass extinction of species in the world, recalling that one of the six former mass extinctions was when the dinosaurs disappeared from the planet 65 million years ago. And finally, Number 9 is because humanity is heading very fast towards a global population of 9 billion people by 2050. The real challenge appears as we are stepping from just around a billion people in fully industrialised economies towards four to six billion people with the purchasing power comparable to an average European.

During the UN climate change talks in Copenhagen, Denmark in 2009, prime ministers and presidents from every corner of the world were expected to deliver a global response to these great global challenges.

But the world had to experience a great failure. It showed the world the powerlessness of the powerful. And out of that has to come an important lesson: We all have to take part and share in the common human responsibility for the Earth, at our own level and in our own circumstances in life.

Image credit: Stockholm Resilience Centre

|

Humanity is the only species whose actions have consequences for the entire planet. At the same time, only humans have the capacity to manage ecosystems, and only we humans can ethically reflect on our actions. We must act in line with that insight.

We experience on a global level the “tragedy of the commons.” The term describes the dilemma that appears as herdsmen share a piece of common grazing land. At an individual level, they make the rational economic decision of increasing the number of cattle one herdsman keeps on the land. But the collective effect would deplete or destroy the commons.

The global tragedy of the commons happens as we, as nations, act as herdsmen: Nations benefit by using more common global resources, but everyone pays the long-term cost. In the long run, we will all lose.

Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to receive the prestigious Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2009, was recognized “for her analysis of economic governance, especially the commons” as her work demonstrated how local groups could successfully manage common property without central authority regulation or the need for privatization. A main conclusion of her research was that the “tragedy” of the commons could be avoided. The commons could be managed bottom-up for a shared prosperity, given the right institutions. If the herders were to cooperate with one another, monitoring each other’s use of the land, and enforcing rules for managing their land, they could avoid the tragedy. It is the principle of common stewardship.

On a global scale, it means forming the right institutions for managing global ecosystems within defined planetary boundaries. In her last article just before she died in 2012, Elinor Ostrom wrote: “We have never had to deal with problems of the scale facing today’s globally interconnected society. No one knows for sure what will work, so it is important to build a system that can evolve and adapt rapidly. The goal now must be to build sustainability into the DNA of our globally interconnected society.” And she concluded: “Decades of research demonstrate that a variety of overlapping policies at city, subnational, national, and international levels is more likely to succeed than are single, overarching binding agreements. Evolutionary policymaking provides essential safety nets should one or more policies fail.”

Andreas (left), talking with farmers in an upland village in Bukidnon about GMO maize, northern Mindanao, Philippines. Photo credit: JA Ignacio

|

Together with forming the appropriate global institutions, we also need a new and basic, universal ethical framework. The Jewish philosopher Hans Jonas formulated a categorical imperative for our time – a time patterned by an unprecedented technological development and ecological impacts of global scale. He stressed, “Modern technology has introduced actions to such novel scale, objects, and consequences that the framework of former ethics can no longer contain them.”

Environmentalists sometimes become so pessimistic due to the global environmental depletion being witnessed and that a planet without humans seems to be better. That is not a perspective supported by Hans Jonas. He comes to the contrary conclusion through the following line of argument: The ability to put him- or herself in the place of the Other (taking the other into account) defines human nature. That creates a basis for the human capacity to reflect ethically on one’s actions, and out of that comes our certain capacity for responsibility. Humanity is also defined by its faculty to picture things, to make images, which reveals the capacity to artificially reproduce resemblance and meaning.

Humans are the only beings that can appreciate value and take responsibility for what we find to have value. We have, in other words, the ability to recognize the good, the power both to protect and to destroy it, and the capacity to make it our business to protect it, and that is itself a good. Therefore, a world with humans is better than a world without.

This led Hans Jonas to suggest a new imperative that included the continued existence of the human species: Act so that the consequences of your actions are compatible with the permanence of genuine human life at the planet earth.

Out of these insights we should develop a worldview built on a planetary awareness or consciousness, a sense of solidarity – rather love – with all human beings and with all other living beings. It may seem a utopian challenge. But isn’t it a way to happiness at the same time? Anyhow it is unavoidable, as humanity is now the largest driver of global change.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Andreas Carlgren works at the Newman Institute, the first Jesuit University College in Uppsala, Sweden, developing an educational program in social science, with focus on environment and justice. He served as the Minister for the Environment of Sweden from 2006 to 2011. In May 2014, Andreas gave the keynote speech for the Conference on Transformative Land and Water Governance that was held in Malaybalay City, Bukidnon, in northern Mindanao, Philippines. Andreas also spent some time before and after the conference to discuss and develop strategies as he pursues, with others, a continuing dialogue with science and values. This article draws from his keynote speech and brief visit to Bukidnon.

|