Sustainable Food Consumption: Where Do We Stand Today?

Food consumption is a major issue in the politics of sustainable consumption and production (SCP) because of its impact on the environment, individual and public health, social cohesion, and the economy. Several key concerns currently high on policy agendas worldwide clearly illustrate how far-reaching the problem is:

- Serious environmental problems related to food production and consumption include climate change, water pollution, water scarcity, soil degradation, eutrophication of water bodies, and loss of habitats and biodiversity. Food consumption is associated with the bulk of global water use and is responsible for the generation of approximately one-fifth of greenhouse-gas emissions (GHGs).

- Population growth and rising economic prosperity are expected to increase demand for energy, food, and water—the so-called energy-food-water nexus (Bazilian et al. 2011)—which will compromise the sustainable use of natural resources and could exacerbate social and geopolitical tensions.

- Approximately 800 million people globally suffer from hunger and underconsumption of food, and a lack of access to safe and sufficient drinking water remains a pressing issue (Coff et al. 2008; Millstone & Lang, 2008). At the same time, 1 to 1.5 billion people are overweight and 300 to 500 million of them obese, an increasing tendency in most regions due primarily to dietary shifts toward more sugar, animal protein, and trans fats.

- Diet- and lifestyle-related health problems such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes are appearing in young age groups (CEC, 2007), significantly increasing health costs (BCO, 2007), while social cohesion is increasingly in danger because health is so closely related to socioeconomic status.

Given demographic changes and the growing global population, these problems are only expected to worsen in the future. Yet, although the relevance of the food dimension for sustainability policies is now widely accepted, efforts are largely lacking toward an integrated policy of sustainable development that covers all actors in the food sector (Reisch, 2006). Except for the challenges of food security and agricultural production, political action plans and programs barely touch upon interdependencies along the food chain and the complexities of modern global food systems. This lack of attention to more systemic issues—and hence the lack of political will for changes—may be one reason why food-consumption patterns show barely any shift toward sustainability.

At the same time, despite considerable progress in the development of sustainability targets and indicators worldwide, there is as yet no commonly agreed upon definition of sustainable food consumption. Perhaps the most encompassing attempt is that introduced by the UK Sustainable Development Commission (2005; 2009), defining “sustainable food and drink” as that which is safe, healthy, and nutritious for consumers in shops, restaurants, schools, hospitals, and so forth; can meet the needs of the less well off at a global scale; provides a viable livelihood for farmers, processors, and retailers whose employees enjoy a safe and hygienic working environment; respects biophysical and environmental limits in its production and processing while reducing energy consumption and improving the wider environment; respects the highest standards of animal health and welfare compatible with the production of affordable food for all sectors of society; and supports rural economies and the diversity of rural culture, in particular by emphasizing local products that minimize food miles. Other researchers have also pointed out that sustainable food styles must fit into people’s everyday lifestyles (i.e., must be “feasible,” available, affordable, and accessible) and should allow for sociocultural diversity (Eberle et al. 2006). Policies for sustainable food consumption, therefore, should learn from and build on evidence from effective consumer policies (Reisch, 2004).

The breadth of this approach clearly illustrates the scope of the issues to be analyzed by researchers, discussed by societal stakeholders, and finally dealt with by policy makers. This article takes a step toward such an analysis by drawing on an extensive literature review to outline the major issues in the current system of food production and consumption and by discussing their impact on sustainable development. Specifically, using an integrative approach to sustainable food consumption and following the definitions provided above, the first part of this article lays out the ecological, social, ethical, health-related, and economic impacts—as well as their interlinkages. For each impact dimension, we provide an overview of the main policy and research issues, key theoretical approaches, major empirical studies, and key available data. To encompass all driving forces and barriers, the study examines the main challenges on both the production and consumption sides.

The second part of the article identifies priority areas and corresponding policy options for SCP strategies for the food sector and concludes with recommendations for the diverse actors in the overall system. The primary aim is to set the stage for the other contributions comprising this special issue that dig deeper into the respective issues.1 We thus undertake more an exercise in scoping and “sounding” than an attempt to fully cover, analyze, and reflect on the field’s many dimensions. Moreover, although the discussion aims to reflect global trends related to sustainable food, the main geographical focus of both the empirical data and the policies presented is the European Union (EU).2

The Food System: The Interlinkages Between Production and Consumption

Major Impacts and Trends on the Production Side

Contemporary food production is becoming ever more globalized and industrialized, and products are subject to increasing standardization. Seasonal varieties are now available nearly all year round and available food products come from all over the world (Oosterveer & Sonnenfeld, 2012). In industrialized countries, agriculture in particular is being intensified and yields per hectare have been steadily climbing over the last several decades. This growing productivity is a consequence not only of rationalization and specialization but also of improvements in plant breeding with and without the use of genetically modified (GM) seeds. Such developments, although expected to continue, also come with untoward side-effects that include further concentration of agricultural industries and decrease in the number (and growth in the average size) of small farms (the so-called “farm crisis”).

Instead of purveying their output in local markets, farmers today are more likely to sell to large, complex supply chains of which they are normally only a tiny part. As a result, only one fourth of the retail food price goes to the farmers, compared to approximately 50% a half century ago (Tischner & Kjaernes, 2007). The loss of the local market to an industrial food system also means increasing “food miles,” the transport distances between farmers, industry, and consumers and this trend carries both cultural and environmental costs (Blay-Palmer, 2008).

Within the EU, food and drink is the second largest industry, employing some 4.8 million people in more than 310,000 companies and achieving a 2011 manufacturing turnover of €917 billion (US$1.2 trillion).3 The food industry, however, is highly fragmented. Despite the small number of large global players selling a huge variety of products worldwide, 99% of all companies are SMEs.4 In fact, available data indicate that, in terms of overall numbers, the European food industry is dominated by enterprises employing fewer than twenty employees and these entities account for 86% of the industry (EC, 2011).

By contrast, food retailing is characterized by high levels of concentration with fewer and larger retail chains sharing the market and competing primarily on the basis of price. Accordingly, the food sector has witnessed the rise of giant corporations that control significant proportions of retail sales, as well as the emergence of internationally operated retail groups. The size of these retailers ranks them among the largest companies in their home countries (e.g., the UK’s Tesco, Germany’s Metro Group, the United States’ Wal Mart). In their role as “supply-chain bottlenecks,” these large retail chains and supermarkets wield enormous market power over both agricultural producers and processors (Oosterveer & Sonnenfeld, 2012). Currently, however, in both American and European food markets, a notable process of bifurcation is taking place between more healthful varieties at relatively more expensive price points and products geared for so-called “value” consumers (often processed foods with high fat and sugar content). Growth rates are higher at both the upper and lower ends of the market, which is prompting a discernible pattern of migration away from midmarket retailing (Oosterveer & Sonnenfeld, 2012).

In 2010, the size of the market for organic food in Europe was €19.6 billion (US$26.5 billion), with the largest single country being Germany, which had “a turnover of €6 billion [US$8.1 billion], followed by France (€3.4 billion [US$4.6 billion]) and the UK (€2 billion [US$2.7 billion])” (Willer & Kilcher, 2012). For European consumers, the most important reason for buying organic food is the belief that it is healthier (Willer & Kilcher, 2012) and there is apparently little difference among European countries in motivation for organic food consumption (Thøgersen, 2009; 2010). It is likely, therefore, that the barriers to purchasing organic produce stem more from the structural characteristics of the living environment, that is, the access, availability, and affordability of the supply.

Regarding the different process qualities of food items, two more trends—overwhelmingly perceived as risks by European consumers—have emerged during the last decade. The first is the application of nanotechnologies, particularly nanoparticles, to a number of consumer products. As a result, food products, and especially food packaging, are expected to become a growing market that will be second only to cosmetics and textiles. The same holds true for so-called nano-enhanced dietary supplements. One especially popular category for such supplements is intended to help people lose weight and is already being sold globally, mainly via the Internet. Nevertheless, the potential contribution of nanotechnologies to sustainable food consumption—mainly less food waste from smart nano-enhanced packaging—is estimated to be rather low (Möller et al. 2009). Consumers in Europe express concern about the application of nanotechnologies in and around food items, primarily because of possible health risks (Reisch et al. 2011).

The second trend is the use of GM products in agriculture, a practice that has been growing steadily on a global basis in recent decades. The area around the world planted with GM crops increased from 1.7 million hectares (ha) in 1996 to 148 million ha in 2010, with an increasing proportion grown by developing countries. In 2010, there were 29 so-called “biotechnology countries” comprising 19 developing countries and ten industrial countries, with 17 of the 29 growing crops on 50,000 ha or more (James, 2010). This development contravenes the expressed desires of the majority of consumers, at least within EU member states, who do not approve of GM products (Gaskell et al. 2010). In Europe, unlike the United States, Canada, or South America, public fear over safety has been widely voiced and has effectively halted the commercial production of GM crops (Millstone & Lang, 2008). The development of these products has also generated global debate, centered particularly on the risk of releasing modified genetic material into the environment, the environmental impacts of the growing use of pesticides, the control of technology by monopolistic multinational companies, and consumer fears of the unknown risks of eating GM products (Pechan & de Vries, 2005; Oosterveer & Sonnenfeld, 2012).

Nevertheless, in general, the EU allows modified seeds and leaves member countries to establish their own procedures for separating traditional and modified crops, and a small but growing number of European countries, including Spain, Portugal, and Germany, allow a few GM varieties. Nevertheless, except for Denmark, the Netherlands, and the Czech Republic, all EU member states have installed “GMO [genetically modified organism]-free zones” (Consmüller et al. 2012), and in the EU the labeling of GM food is mandatory for all products made from or containing GMOs, as well as all GM additives and GM flavorings. Foodstuffs produced from animals fed with GM fodder, however, do not fall under this legislation. Hence, Germany and Austria have introduced “free from GMO” labels that are applicable to foodstuffs to which neither GM additives nor GM feed have been introduced.

Major Impacts and Trends on the Consumption Side

In industrialized countries, the range of available food products is extensive and, because most are affordable all year round, the notion of seasonality has lost its meaning. In addition to an abundant choice of healthy fruits and vegetables all year, consumers in most EU countries benefit from the comparatively low prices and high convenience that have accompanied changes in food production and globalization. The downside of this process, however, is that consumers have become increasingly estranged from the production of their food and, despite the recent recurrence of regional food and new trends like slow food and organic produce, consumer knowledge of seasonality and regional supply has withered (e.g., Tischner & Kjaernes, 2007; Blay-Palmer, 2008).

On an individual level, food habits and preferences are shaped by cultural traditions, norms, fashion, and physiological needs, as well as by personal food experience and exposure to the consumption context (i.e., foodstuff availability and accessibility). Such preferences and tastes, together with finances, time, and other constraints (e.g., work patterns, household decision making) influence food consumption. Price, in particular, is a major decision criterion, but food preferences also differ significantly by household characteristics such as age, income, education, family type, and labor-force status. Food styles and demand additionally vary greatly among EU member states and this diversity has prompted researchers to cluster consumers into groups representing different “nutrition styles” or “food styles” so that they can be targeted by social marketing with “proper food” messages (Michaelis & Lorek, 2004; Friedl et al. 2007; Schultz & Stieß, 2008).

Despite individual, (sub)cultural, and national differences, it is still possible to identify some general food-consumption trends relevant to sustainable development and already evident in most EU countries (as well as in those nations that are part of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). Probably the most important development in terms of impact on climate and health (Shindell et al. 2012) is the increase in meat consumption (especially pork and poultry) and fresh dairy products that has taken place over the last few decades (EEA, 2005; OECD & FAO, 2011). Also on an upswing is demand for highly processed meals (fast and convenience food) (RTS Resource Ltd., 2006), a trend attributable to the fact that time spent on food purchasing and cooking, as well as on eating, has decreased significantly over the past few years (Hamermesh, 2007). Socially, home meals and their preparation are losing their significance as loci for communication and structuring of everyday lives, while convenience products, fast food, and restaurant meals are gaining in importance. Out-of-home consumption now accounts for a significant and growing proportion of European food intake. For example, 35% of the Belgian population consumes over 25% of its daily energy intake outside the home (Vandevijvere et al. 2009), and 27% of participants in a representative Spanish study reported eating out at least twice a week (Bes-Rastrollo et al. 2010). Such varying food habits (e.g., home-made versus ready-to-eat or school-provided lunches) have a clear impact on both climate and eutrophication (Saarinen et al. 2012).

At the same time, food consumption is increasingly furnished with symbolic meaning and hedonic experiences, and “social food” has become ever more significant in combatting the perils of an individualized society. Today, food marketing promises solutions not only to indulgence and prestige problems, but also to health and fitness concerns (Schröder, 2003). Indeed, with respect to both convenience food and food services, high-quality and health-oriented products and organic foodstuffs have become increasingly important (Tempelman, 2004). As a result, although the market share of organically grown and fairly traded food products remains small in absolute terms, both categories have grown steadily, and even remained quite stable during the financial crisis (Willer & Kilcher, 2012). Well-being and healthy lifestyles have even become a social and economic megatrend. Nevertheless, overweight conditions and obesity are spreading worldwide, and the rate of obese adults has more than doubled over the past twenty years in most EU countries (OECD, 2010b), a trend that is hardly surprising given that the food supply in the EU-15 countries is a third more than is required for a healthy diet.5 In many industrialized countries, this food wealth, combined with increasingly sedentary lifestyles and modern diets, is leading to rising obesity, particularly among children and teenagers, but also among lower socioeconomic groups with low access to fruits and vegetables (WHO, 2005).

Concerning food-market transparency, the complexity of food choice has increased and the more options and novelties the more troublesome the information search and the more complex decisions are for consumers. Although information brokers—from independent testing institutes to commercial food magazines to food activists and Web 2.0 slow food communities—may work to reduce complexity for a few people, many consumers report being overwhelmed and would rather adhere to their habitual choices (Mick et al. 2004). In fact, the success of food retailers such as Trader Joe’s, which offers a very narrow food assortment, results from the attractive mix of little choice (and hence, low search costs) and the high quality of the organic products that they sell at relatively low prices—something that full-line super- and hypermarkets cannot match. The growing consumer uncertainty in the food sector has been fueled by a decade of food scares, combined with differing expert evaluations of risk, contradictory and short-lived nutrition information in the media, pronounced variety of available food products, and globalization and distancing of food production (Bergmann, 2002). Hence, the multitude of coexisting food labels, rather than helping consumers navigate, has led to consumer confusion and information overload that prevents quick retrieval of relevant information. As a result, (re)building consumer trust in the food information provided by both the state and the market is a key challenge (Kjærnes et al. 2007).

Finally, one-third of food globally is wasted (Gustavsson et al. 2011), particularly during the retail process and by consumers. For instance, according to one recent study, British households discard 33% of the food that they buy, 61% of which could have been eaten if it had been better managed (Ventour, 2008). Likewise, in Germany, 61% of food waste originates from households, two-thirds of which could have been avoided or partly avoided (Kranert et al. 2012). The reasons for such wastage range from poor menu planning and a general lack of food competence (i.e., knowledge of food freshness and storability) to huge package sizes enabled by large home-storage capacities and the attractiveness of quantity discounts at points of purchase.

Unsustainability of the Current Food System: Dimensions and Factors

Given escalating rates of obesity and diet-related diseases, excessive food miles, food scares and food insecurity, the spread of fast food culture, and increasing food waste—all of which have consequences for global climate change—the western food system is clearly unsustainable (SDC, 2009). To achieve sustainable food consumption, the problems of both over- and under-consumption must be confronted, together with food-safety issues in affluent societies and food-security issues in poorer regions. This section therefore briefly reviews the environmental, health-related, ethical, and economic aspects of food consumption and the key challenges that constitute contemporary public debate.

Environmental Aspects

Food consumption is one of the private consumption areas that has the largest impact on the environment; among the EU-25 countries approximately one-third of households’ total environmental impact—including energy use, land use, water and soil pollution, and GHG emissions—is related to food and drink consumption (EEA, 2005).6 The overall impact and private household space for maneuvering, however, also depend on the decisions of other actors in the production chain, whose roles and responsibilities—particularly regarding environmental “hot spots”—are highlighted below.

Agriculture

The main environmental effects from food arise in the primary production stage. Agriculture is a major source of such impacts through land usage and soil degradation, water consumption, eutrophication and water pollution, monocultures that cause biodiversity loss, and introduction of hazardous chemicals through synthetic pesticides and mineral fertilizers. In terms of energy use, agricultural production is responsible for about 30% of the food sector’s total energy demands (Owen et al. 2007), 40% of which result from the production of chemical fertilizers and synthetic pesticides (Heller & Keoleian, 2003). Another more indirect cause is the production of cattle fodder (Tempelman, 2004), which in terms of primary production accounts for nearly half of the GHG emissions from food consumption (Tukker et al. 2006). Simultaneously, climate change is dramatically affecting agriculture and will do so increasingly (Schaffnit-Chatterjee, 2009). Yet research on the environmental impacts of organic production (e.g., FAO, 2003; Shepherd et al. 2003) shows that, depending on the products involved, organic farms use 50 to 70% less energy (direct and indirect) per unit of production than conventional farms, mainly as a result of different fertilizer use. Organic production also has clear benefits for biodiversity on agricultural land, although lower yields may mean that a larger land area is required than under conventional production methods. In milk production, however, the advantages are less clear, primarily because of the higher output of conventional dairy farming and the higher GHG emissions from grass-fed cattle. Nevertheless, animal treatment is typically better on organic farms, and cows are less likely to be lame or stressed or to carry disease (Owen et al. 2007).

Industry

Because the food industry encompasses all stages of the value chain beyond the farm gate and before food purchase and consumption, it includes manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and food-service providers. The activities of this industry can degrade the environment in numerous ways, including through the generation of air emissions from grinding grain, bulk-product transfers, and silo vents; the contamination of land from accidental oil spills and past site use; the creation of noise pollution from food-manufacturing equipment, grinding machinery, and packaging lines; the (over)use of resources such as water, energy, and food-packaging materials; the disposal of out-of-date products, peelings, animal byproducts, food packaging, food-manufacturing equipment, and effluent-plant sludge; and the discharge of water from effluent plants, accidental spills, and cooling towers.7 Within the UK, for instance, the food industry accounts for 14% of the energy consumption by all businesses, seven million tons of carbon emissions per year, about 10% of all industrial use of the public water supply, approximately 10% of the industrial and commercial waste stream, and 25% of all heavy goods vehicle kilometers (DEFRA, 2008).

Consumers

The environmental impacts of food consumption in households, restaurants, schools, and other institutionalized settings result mostly from the handling and preparation of food, that is, storage (primarily freezing), cooking, and dishwashing. The choice of diet and food types, however, is also relevant in that, for example, (red) meat and dairy products cause by far the highest GHG emissions. In fact, within the EU-25, meat and meat products contribute to between 9 and 14% of total releases, with the second most relevant food products being milk, cheese, and all types of dairy products (Tukker et al. 2006). Cereals, fruits, and vegetables, in contrast, contribute comparatively low levels of GHG emissions (Dabbert et al. 2004; Carlsson-Kanyama & Gonzalez, 2009). In terms of storage, cooking, and dishwashing, the environmental impacts depend in particular on the energy efficiency of the relevant household appliances (Quack & Rüdenauer, 2007). Another factor that effects the environment, one too easily neglected by consumers, is the means chosen for the “last mile of transport” (Reinhardt et al. 2009). That is, the tendency to travel by car to out-of-town supermarkets for food purchases counteracts consumers’ own interest in environmentally sound grocery shopping, a typical “tragedy of the commons” situation where individual and social interests stand in contradiction. Finally, at the very end of the food chain, the main issue, as previously discussed, is waste and discarding of food.

Environmental “Hot Spots”

Although the food-related factors affecting the environment are manifold, if policies and corporate strategies are to effectively and efficiently make a difference, they must necessarily concentrate on “hot spots.” The academic literature generally agrees upon a number of these primary environmental impact categories related to food consumption and production, including GHG emissions, water consumption and pollution, eutrophication, land use and soil degradation, and biodiversity loss.

One of today’s main environmental challenges is to contain climate change to a maximum of a 2°C global average (IPCC, 2007). The primary contributor to such global warming is GHG emissions, caused in particular by the use of synthetic pesticides and mineral fertilizers, livestock farming (especially methane and nitrous-oxide emissions), transportation, food packaging and processing, and cooling and cooking. In fact, 45% of all nutrition-related GHG emissions derive from food production (agriculture, processing, and transportation), while the remaining 55% are generated by storage, food preparation and consumption, and to a minor extent by the transportation of food purchases. Eating out also contributes substantially to GHG emissions (Eberle et al. 2006). The seriousness of this issue is clearly demonstrated by calculations for Germany that food accounts for about 16% of GHG emissions, the same share as mobility (Eberle et al. 2006), and by the fact that the UK’s food production and consumption is responsible for about 18% of its GHG emissions (BCO, 2008).

Agriculture also consumes most of the freshwater used in the world, accounting in some developing countries for up to 90% of usage. Changes in diet place even higher pressure on water resources (Schaffnit-Chatterjee, 2009). For example, one study by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (2009) reveals that agriculture accounts for about three-quarters of German water consumption, about 40% consumed in Germany itself but about 60% “imported” through agricultural products from outside the country. Overall, the study estimates per capita water consumption of nearly 4,000 liters per day just for food, which includes the so-called “virtual water” consumed during agricultural or manufacturing production.8 At the same time, agriculture is one of the main polluters of water bodies, due mainly to the appropriation of nitrates from the soil and the use of pesticides. In fact, experts expect not only a further increase in chemical applications but also increasing absolute contamination stemming from their long persistence in both soil and water (SRU, 2004). Most particularly, agriculture is one of the main sources of water eutrophication, primarily through the use of fertilizers and nitrous-oxide emissions from livestock breeding (SRU, 2002). Agriculture also demands land for crop cultivation and animal management, which requires especially high land usage, primarily for cattle-feed cultivation. This pattern of land-use activity is expected to multiply exponentially in coming decades to meet the growing demand for meat in developing countries (Tempelman, 2004). Even without such changing trends in diet, agricultural production will have to be increased in the future to feed a growing global population. For instance, the World Bank (2007) projects that cereal production will need to increase by 50% and meat production by 85% between 2000 and 2030. At the same time, however, experts estimate that since the 1950s, about 22% of all cropland, pasture, forest, and woodland worldwide has suffered soil degradation (Schaffnit-Chatterjee, 2009).

Finally, compared to other sources (e.g., households, industries, transport, energy), agriculture also has the highest negative impact on biodiversity, most especially due to biodiversity loss from the use of agrochemicals associated with intensive farming. In some places, the replacement of local varieties of domestic plants with high-yield or exotic alternatives has also broken down important gene pools (Schaffnit-Chatterjee, 2009). Yet, biological diversity is critical for food security and this awareness has prompted the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2010) to actively promote the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. In meeting this goal, organic agriculture has a substantially lower environmental impact than conventional agriculture (Foster et al. 2006).

Health Aspects

Over and Under Nutrition, Health, and Well-Being

Under-nutrition and malnutrition exist to a considerable degree in both industrialized countries and countries in transition. Even in Europe, about 5% of the overall population is at risk of malnutrition, and among vulnerable groups—the poor, the elderly, and the sick—this percentage is still higher. At the same time, people worldwide face an increase in such food-related health problems as cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes because of rich foods, modern diets, sedentary lifestyles, and overeating. Key diet-related factors are the high intake of saturated fat, salt, and sugar and the low consumption of fruits and vegetables. It has been estimated that 70,000 premature deaths in the UK could be avoided each year if diets matched national nutritional guidelines (BCO, 2008). In fact, according to the British Cabinet Office (2007), food-related ill-health costs amount to £6 billion (US$9.3 billion) per year (or 9% of National Health System costs), and malnutrition, mainly in the elderly, costs public services £7.3 billion (US$11.3 billion) annually. The BCO (2007) also expects obesity, a risk factor for many serious health conditions, to continue increasing and further undermine health and well-being, health-service costs, state benefits, and the economy. Hence, stemming obesity, particularly in children, is a major challenge for sustainable development (WHO, 2008).

In the affluent world, excess weight gain currently ranks as the third greatest risk factor after smoking and high blood pressure for all premature deaths and disabilities (IASO, 2009). Among children especially, obesity levels have risen in the EU during the last three decades to about one-third of the population (CEC, 2007). By 2050, half of the UK’s population is projected to be obese (DEFRA, 2008), leading to an increase in chronic conditions including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type-2 diabetes, stroke, certain cancers, musculoskeletal disorders, and even a range of mental health conditions. Obesity is most prevalent in lower socioeconomic (SES) groups, and particularly in women, which reduces their access to economic and social life chances (DEFRA, 2008). Women in lower SES groups also seem more vulnerable than men because of different environmental pressures in an “obesogenic environment” (Robertson et al. 2007). These women are also more likely to give birth to either under- or overweight babies (both risk factors for later obesity), and are less likely to follow recommended breastfeeding and infant-feeding practices (also linked to obesity risk). Hence, added to the public health and social care costs are personal costs like the impact on well-being of morbidity, mortality, discrimination, and social exclusion (DEFRA, 2008; Reisch & Gwozdz, 2010). Nor are such problems confined to the developed world: with the global spread of western high-fat, high-sugar diets, obesity has also become a problem in less affluent countries. Admittedly, at present, adiposity and overweight status in these countries remain primarily problems of the upper classes with access to modern diets (Witkowski, 2007; IASO, 2009). However, as such diets become more available, the consumption habits of the middle classes will follow.

Despite these findings, as Cohen (2005) rightly notes, scholarship on sustainable consumption, like policy making, has only very recently taken up nutritional excess, a fact that he attributes to the divide between environmental and nutritional policy. In fact, Lang & Heasman (2004) suggest that the development of a more integrated view is being hampered by an on-going “food war” between three schools of thought: the long-dominant “productionist” paradigm of food and health politics, a “life-science integrated paradigm” (i.e., with life sciences having the lead as regards topics and priorities), and an “ecologically integrated paradigm” that also includes the costs for the ecological system.

Food Safety

Health risks also result from the presence of unwanted substances in food products, including pathogenic organisms, toxic substances (e.g., pesticides and heavy metals), and contaminants. In Europe, the most serious food-safety issue is food-borne illness from food poisoning and poor hygiene. Despite this concern (or perhaps because of it), more food allergies have been reported over recent years, and the number of people with food allergies is still increasing (DEFRA, 2008). Because food risks are socially channeled and mediated, however, there is often a wide gap between perceived health risks and objective risks (Blay-Palmer, 2008). For instance, German consumers primarily fear health risks from food additives even though, objectively construed, the risks from active hormonal substances are much higher. Moreover, although the health risks from the use of (broadband) antibiotics in livestock breeding play only an ancillary role in public awareness, they are generating an increasing number of resistances in pathogenic organisms, which in turn present serious risks for human health (Dettenkofer et al. 2004).

Ethical Aspects

At the heart of sustainable consumption lies the idea of ethically responsible food production and consumption. This concept encompasses multiple aspects, ranging from food and water security to fair trading conditions to species-appropriate livestock breeding. The main areas of ethical concern regarding food are as follows (Coff et al. 2008). First, the supply of food and access to clean drinking water available to human beings should be just and fair (food security). Second, food should not endanger the health of consumers because of pathogens or pollution (food safety). Third, ethical issues need to be addressed in relation to new developments in nutritional research and technology, particularlyfunctional foods, nano-enhanced foods, and GM foods, as well as personalized nutrition. Fourth, observation of specific production practices in the food chain affecting animal welfare, the environment, and (un)fair working conditions has given rise to a demand for “ethical traceability” of key consumer concerns. These ethical considerations have very concrete consequences. For instance, meeting the needs of a growing global population and the increasing demand for meat in developing countries will require substantial growth in land usage at a time when most productive cereal areas in North America, India, and China will be approaching their biophysical limits (Tempelman, 2004).

One essential aspect of ethically responsible food consumption today is fair trade and working conditions. The European market for fairly traded products is growing, with bananas, coffee, orange juice, tea, and chocolate most often sold (FLO, 2006; 2010). All of these products have been marketed in several Western European countries since the 1980s and 1990s (Oosterveer & Sonnenfeld, 2012). At the same time, several non-European countries, including Australia, the United States, and Canada, have seen notable growth rates of these products, making fair trade a global phenomenon. As a result, market shares have been rising rapidly since the early 2000s, with Switzerland and the UK having relatively high penetration but Japan demonstrating slow uptake to date. Overall, the growth of fair trade sales has been impressive, reaching well beyond €3 billion (US$3.9 billion) in 2009—and this is in spite of the 2008/09 economic crisis (Oosterveer & Sonnenfeld, 2012). Interestingly, fairness in trade is not only an issue for developing nations. In European countries, farmers are also demanding fair payment for their produce. For example, in Germany, some farmers, retailers, and dairies have become organized into a cooperative to offer “fair milk,” whereby the income of farmers is secured through long-term contracts based on prices slightly above the fluctuating market price.

Another important aspect of consumer awareness is animal welfare, especially in European countries such as the Netherlands, Germany, and the UK. This concern has given rise to the development of different formats for food labels specifically evaluating animal welfare in the production process (SAB, 2011). For example, the production of eggs by cage-free hens and the participation of retailers in the Global Animal Partnership animal-welfare certification program have been notably visible developments.

Also a subject of increasing debate in industry, civil society, and the political arena is the contribution of corporate social responsibility (CSR) regimes, including those within the food sector (Hartmann, 2011). One means of managing ethical workplace conditions throughout global supply chains is to follow international standards, such as Social Accountability Standard 8000 (SA 8000) or the International Standards Organization standard for CSR (ISO 26000). According to a survey of 300 executives from retail and consumer-goods companies in 48 countries, ethical sourcing will also figure prominently as a food (retail) sector issue in the future (CIES–The Food Business Forum, 2007).

Economic Aspects

The share of total European household expenditure on food has declined steadily with rising incomes, ranging between 10 and 35% of total household consumption outlays in 2005, with the smallest shares in the EU-15 member states and the larger shares in new member states (EEA, 2005). Compared to previous years, international food prices are likely to remain, at higher levels, primarily because of the escalated cost of inputs. In the EU overall, the price index for food rose by almost 20% between 2005 and 2012 (Eurostat, 2012).9 Rising food prices create serious difficulties for vulnerable, low-income households that spend a substantial proportion of their income on food (Michaelis & Lorek, 2004).

Food from organic production is also more expensive than its conventional equivalents, on average around 17% more costly in Germany (GfK, 2007), and although the price of seasonal vegetables can be comparable, meat and meat products, particularly, are more costly. These price differences—which result from lower yields, more expensive materials, and more labor-intensive production methods—are even more pronounced in other countries around the world, ranging from 10–50% depending on product, season, and retailer. In Europe, a few innovative retailers are actively working to reduce the price difference. For example, the Dutch chain Albert Heijns maintains a permanent 5–35% price reduction on a selection of 25 organic food products while Auchan in France has set a limit of 25% on the its margins for fair trade products (UNEP, 2005). One of the leaders in the Danish market, Coop, decided as far back as 1993 to fully eliminate the sales-price difference between organic milk and conventional milk, thereby bringing about an early breakthrough of organic products in Denmark (Schmidt et al. 2009). The same chain in Sweden has a specific pricing policy on organic food: instead of the normal price percentage mark-up, the same amount is added for organic products as for the conventional alternative product. Likewise, Denmark’s SuperBrugsen regularly combines promotions of sustainable products with discounts, making it easier for customers to trial these options (Schmidt et al. 2009). SuperBrugsen and KIWI Denmark and Norway also have “organic weeks” or “organic months” in which all organic products are offered with a price reduction of the full value added tax (VAT), which amounts to 25%.

Policies for Sustainable Food Consumption

Overview

In terms of sustainability promotion, the food-policy domain is quite complex. In addition to the environmental, ethical, and economic aspects of food consumption that have regional, national, and global impacts, public health concerns are an integral factor. In general, policy makers trying to enhance food-system sustainability have three major types of instruments at their disposal: information-based, market-based, and regulatory (Lorek et al. 2008). Recently, however, this toolbox has been enlarged with “nudging” instruments, such as choice architecture, in which the person or organization “designing” the choice can harmonize the default outcome with the desired outcome (see Thaler & Sunstein, 2008; Sunstein & Reisch, 2013). Sometimes referred to as behaviorally informed social regulation (Sunstein, 2011), this policy approach has been integrated into various political applications, including consumer policy (OECD, 2010a). In the food and health area, particularly, nudging consumers toward more sustainable or healthier choices—for example, by moving the soda machines to more distant, less visited parts of a school or locating the salad bar in the middle of the cafeteria where everybody passes by—has been quite successful (Just & Wansinck, 2009; Reisch & Gwozdz, 2013).

Ideally, the goal is to build a coherent policy framework for appropriate action and to incentivize, enable, and empower the actors along the food chain to engage in more sustainable production and consumption. Governments can also influence markets and mindsets by stimulating and supporting businesses in voluntary self-commitment. Finally, governments and public bodies are themselves powerful role models and market makers that, by choosing sustainable alternatives by default, can help to create critical demand (public procurement). All these efforts should be coherent with other relevant policy initiatives, such as agricultural and consumer policies (Reisch, 2013). To give an overview of current practices, the next section summarizes the main policy instruments used today in relation to sustainable food consumption.

Policy Instruments: The Scope

On the production side, the European agricultural sector is a highly regulated market in which the regulatory and market-based instruments already in place are targeted primarily at production. They are, therefore, not the major focus of this discussion. Nevertheless, certain of these instruments—for example, the financial support provided to organic producers via subsidies under the reformed Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)—probably create a stronger push for increased availability and affordability of organic products than many other instruments discussed in relation to sustainable food consumption.

On the demand side, national governments generally play a relatively weak role in managing the adverse effects of (over)consumption. The main driver to date behind regulatory command and control instruments in the field of food consumption and production is the need to respond to acute threats to the life and health of citizens. Only recently has governmental attention about food intake extended to everyday diet and health issues. Nevertheless, these concerns, although they are slowly resulting in political measures (especially as they relate to obesity and its health impacts), are designed mostly for information provision and rarely take the form of overt regulation. Rather, “command and control” is usually applied only in cases that can be left neither to voluntary agreements (VAs) nor to the market because of the high risks involved or because of time pressure and doubts about VA effectiveness. Thus, regulation concentrates on food-safety issues and aims to protect consumer health, lives (e.g., through hygiene standards), and economic interests (e.g., through competition regulation).

With regard to food-sector sustainability, governments and their administrations come into play mostly as organizers of (public) certification, standardization, and inspection, as evidenced by the state-run labeling of organic and regional foods in about half of EU countries (Organic Europe, 2011). Such labels constitute an important tool for raising consumer awareness about the health and environmental aspects of food and for facilitating informed decision making (Eberle et al. 2011). Nevertheless, in terms of changing buying decisions, the effectiveness of labeling is limited (Larceneux et al. 2012). The main impact seems to be on the supply side since such labels have proven valuable marketing tools in saturated markets.

Another relatively recent approach to promoting sustainable food consumption is self-regulation in the form of sustainable public food procurement (or guidelines for procurement and catering) in such public bodies as kindergartens and schools, staff cafeterias in the public sector, prisons, and hospitals (Wahlen et al. 2012). However, examples from various member states, especially the UK and Sweden, demonstrate that such self-regulation, even though it requires much time and effort, effectively improves food quality only when government closely monitors the initiatives (Dalmeny & Jackson, 2010). In fact, one recent report concluded unambigiously that “the only way to achieve a radical improvement in public sector food—for example in our schools, hospitals, and care homes—is for government to introduce a new law which sets high, and rising, standards for the food served” (Dalmeny & Jackson, 2010).

In contrast, market-based instruments targeting households and individuals seem far less prevalent than regulations in the food domain, despite being applied upstream in the food-supply chain (e.g., subsidies to organic farmers). However, several national governments recently launched initiatives to tax certain food types (e.g., junk food) or food components (e.g., certain fats in Denmark) (Nicholls et al. 2011). Nevertheless, the dominant policy instruments in the food domain are information-based and education-oriented tools thatfocus on raising awareness and are often accompanied by voluntary strategies encouraging self-commitment, cooperation, and networking. These interventions contradict social trends insofar as increased out-of-home and ready-made food consumption, and the rise of other priorities in formal school curricula, tend to result in declining education in growing, processing, cooking, and storing food. In some places, however, efforts continue to develop “food literacy” among young consumers with regard to choosing and preparing healthy (e.g., more fruits and vegetables) and sustainable (e.g., organic, regional, fair trade) food. For instance, as one element of a national food strategy, France has recently started systematically training school children’s sensory and taste competences. Related initiatives include an explosion of interest in school-gardening initiatives and efforts to reform school-meal programs.

Achieving behavior change in favor of more sustainable food consumption, however, is a long-term goal that involves several stages and requires the constant efforts of all actors involved. Yet, barriers at the institutional, informational, infrastructural, and personal levels are pervasive. Nevertheless, with the recent rise of new, alternative agrofood networks, small farmers’ movements, and different forms of community-supported agriculture (CSA) (Oosterveer & Sonnenfeld, 2012), policy makers do have effective tools to ease the availability, affordability, and accessibility of sustainable food supply, helping to “make the sustainable choice the easy choice.”

Overall, agreeing on a positive definition of what constitutes sustainable food choices remains difficult, a challenge fuelled by inconclusiveness and sometimes even contradiction in the scientific evidence.10 Research and policy do seem to agree on the main drivers of nonsustainability in the current food domain. These include, first, the distance between food consumers and producers (in miles, as well as in minds). Second, is the significant loss of biomass between the field and the table (including the waste generated). Finally, the high consumption of animal products in the form of meat and dairy products is a priority. These three issues constitute the critical aspects of nonsustainability, which governments should address with some urgency.

The Need for Coherent Policy Frameworks

Despite growing attention to the food domain on the policy level, approaches that integrate the different sustainability issues into coherent policy frameworks or action plans—or, at least, into noncontradictory policy tools—are rare. The same is true for explicit strategies for sustainable consumption. Not only do nutrition and food policies, environmental policies, and health and social cohesion policies seldom link to one another, but explicit policies for sustainable consumption in general and for food consumption in particular are uncommon. Moreover, policy toolboxes tend to be designed one dimensionally for specific policy domains, and the policy tools adopted primarily target individual consumers. Hence, although it has become clear that systemic changes in the prevailing socio-technico-cultural-econo-political system are necessary for a move toward sustainable consumption, the role of societal innovations is often underestimated (Brown et al. 2012).

Most particularly, in the face of the dominant, highly concentrated, powerful retail industry that characterizes the European food domain, governments tend to restrict themselves to a marginal role and to noninvasive instruments, such as consumer information and education (Mont, 2008). They also seem reluctant to implement strict national food policies because of the risk that sustainability goals and policies might conflict with European law. For instance, the EU recently asked Sweden to withdraw its National Food Administration’s (NFA) proposed guidelines for climate-friendly food choices because they are in tension with European trade goals. Specifically, the EU Commission found that the recommendation to eat more locally produced food contravenes the EU’s principles for the free movement of goods.11

Governments also lack vision of the possible forms that sustainable food systems might take. An understanding of the difference between sustainable food and sustainable diet seems a crucial starting point. For instance, an individual can consume very healthy, sustainably produced food but still eat too much or too little of it. Alternatively, food could come from sustainable farming but still be highly processed and overly packaged. Hence, a priority for governmental activities is to develop integrative, cross-sectoral, population-wide food policies on such issues as agriculture and food supply, availability and access to food, physical activity, welfare and social benefits, fiscal policies, animal welfare, and information and social marketing (Robertson et al. 2007). On a global scale, such an integrative paradigm would be even more important. Yet, if the differences between Europe and the United States in how to approach sustainable development are indicative (Robertson et al. 2011), integrated policies will be exponentially more difficult to develop.

A review of current European sustainable development strategies (SDS) and action plans highlights the following major goals for sustainable food consumption (in order of priority): improving health and lowering obesity levels, increasing organic food consumption and production, decreasing GHG emissions, and reducing food waste. These goals have been the focus of several major reports in recent years (e.g., EC–SCAR, 2011; UK Parliament, 2012) and serve as the starting point for both our analysis of policy instruments and the search for synergies and coherence. Because SDSs are a result of social debate in the various countries, their explicit goals reflect mainstream thinking about the areas in which policy instruments are appropriate and necessary. At the same time, however, they neglect other relevant aspects of food and drink sustainability, including the social and socioeconomic dimensions on both global and local levels. As already pointed out, the UK’s Sustainable Development Commission (2005) has emphasized the need to move beyond reflections on “safe, healthy and nutritious food” to include consideration of “the needs of the less well off”; that is, policy must take into account decent economic, living, and working conditions for those along the food-production chain, including respect for animals and support for rural economies and cultural aspects.

Two other issues prominent in recent academic discussion have not yet received sufficient attention from policy makers: a nation’s self-sufficiency in terms of food supply and the uneven impacts of food production on soil. These rather complex issues are made all the more challenging by World Trade Organization (WTO) rules and EU policies promoting intercountry trade. Nevertheless, they need to be addressed in the near future, especially given the documented adverse effects of policies that increase food transportation from one country to another. As mentioned above, about 40% of food is wasted in the food chain (Mont, 2008). These issues have also been taken up by experts in water footprinting, a field that highlights the degree to which embodied water resources reflect inequitable trade flows (Hoekstra, 2013).

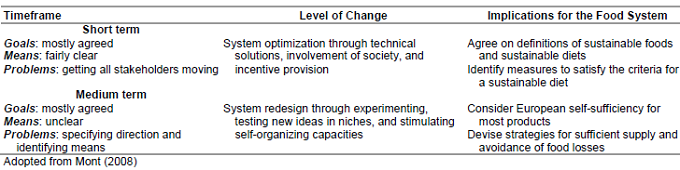

Given the goals already adopted as part of SDSs and the more extensive objectives that have recently entered the debate, two requirements appear relevant for building a framework for sustainable food consumption and production: short-term action on the agreed problems and medium-term specification of how to redesign the food system(s) (see Table 1). Also needed is a parallel debate on a “European food model” and its common values (e.g., as regards GMOs and nanotechnologies) that includes the possibility of a green economy strategy for the food sector.

Table 1: Short-term and medium-term requirements for a sustainable food-policy framework.

TO ENLARGE, CLICK HERE

To this end, we now review existing and desirable policy instruments and suggest a way to combine them to maximize synergies.

Analysis of Existing and Required Policy Instruments

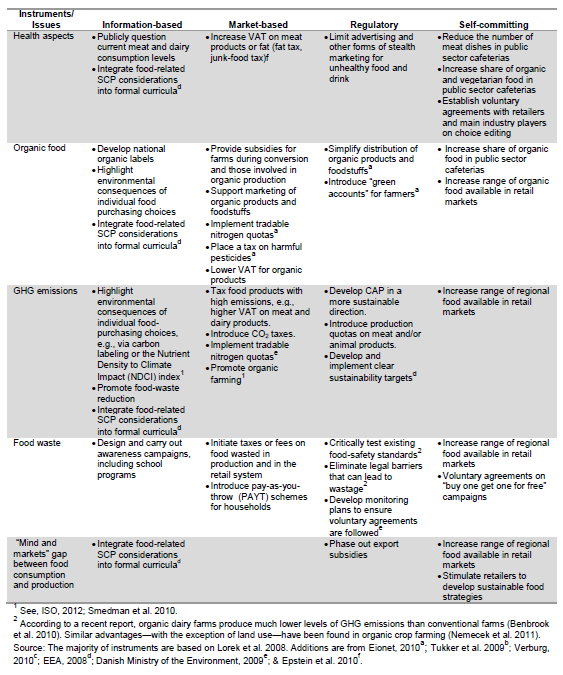

Table 2 summarizes the food-policy instruments currently in use in EU member states and delineates how different types of tools can work in concert toward a singlegoal (table rows) and how they can be used to support differentissues simultaneously (table columns).

Table 2: Framework of policy instruments to promote sustainable food systems.

TO ENLARGE, CLICK HERE

Information-based Instruments

On the European level, a significant amount of food-related information and disclosure is already regulated. Consumers have become accustomed to packaging that includes “best before” dates, ingredients, health claims, origins, organic content, environmental details, serving suggestions, and recipes. Nevertheless, although product-based consumer-information tools are important, they often lead to overload, an old but frequently ignored insight (Miller, 1956).

A number of practical barriers also exist, such as the readability and comprehensibility of the product information provided. As a rule, consumers tend to rely on front-of-the-package, easy-to-see, read, and understand signals, as well as shelf-display information like unit pricing (see Hersey et al. 2011). However, the secondary effects of such information tools are often at least as important as the primary effects of better individual choices. These include impacts on social norms (e.g., regarding packaging and food waste) and quality standards, which in turn steer the industry toward healthier product formulas and provoke public debate on relevant topics.

In politics, awareness campaigns and social marketing activities are promising methods of choice, particularly in combination with other policy tools such as limits on advertising. In industry and retail, labels are increasingly seen as a business opportunity because they allow companies to participate in growing organic and fair food markets. For many years, attempts have been made to reduce this complexity by developing metalabels, for instance, a combined socioecological “sustainability” labelto cover all relevant aspects (e.g., Teufel et al. 2009; Eberle et al. 2011). However, as yet no such instrument has emerged.

Market-based Instruments

In terms of market-based instruments, governments apply both “carrot” and “stick” approaches, including, respectively, subsidies for healthier foodstuffs (e.g., reduced VAT for fruits and vegetables) and taxes and fees on harmful or unsustainable food and drink. The goal of these latter interventions is to create financial incentives that steer market-actor behavior. Such financial instruments are potentially powerful tools because, in the food domain, price is a key decision criterion for consumption and hence a critical competitive advantage. Hence, taxes serve as a stronger incentive than subsidies for consumers to switch to another product alternative and/or to another form of need fulfillment. Taxes and fees also bring in revenue that the state can use to finance information- and education-based policies, for example, promoting organic food consumption by combining an organic label with reduced VAT for organic products (EEA, 2008).

Another widely used option is the introduction of subsidies for farmers who convert to organic practices and/or those currently involved in organic production. The policies introduced so far, however, have failed to adequately address the necessary reduction in animal-product consumption, despite ranging from taxation of food products with high GHG emissions or significant ecological footprints to a higher VAT on meat and animal productsand even an additional “fat tax” on saturated fats in Denmark (Ekstrand & Nilsson, 2011; Smeds, 2012). The latter, for instance, although its outcomes have yet to be formally evaluated, most clearly affects lower SESs that spend relatively more on basic foodstuffs and tend to buy fattier meat.

Regulatory Instruments

One critical step in the pursuit of a sustainable food policy is for governments to define and enforce clear national (and supranational) sustainability targets in the food domain, such as a general reduction of GHG emissions or land-usage goals (EEA, 2008). Proper implementation and promotion of these targets must be ensured through independent monitoring. However, although some EU member states (e.g., the UK and Denmark) are spearheading such initiatives and devising goals, plans, actions, and processes, others remain only in the early stages of development.

The major framework shaping food supply and demand in Europe is the CAP which, as a medium-term strategy for a sustainable food system, could adopt the phasing out of export subsidies for agricultural products and the shifting of those funds toward SME-scaled production for local and regional needs (BirdLife International et al. 2009). Such a strategy would strengthen rural economies by ensuring a viable livelihood for farmers, processors, retailers, and their employees. At the same time, the narrowing of the distance between production and consumption—both in minds and markets—would help to reduce not only food miles but also preferences for industrially prepared meals over fresh, local food. The most important contribution for lowering GHG emissions, however, would be reduced consumption of meat and dairy products, which would require consideration of (national) production quotas as an administrative instrument that could, according to preliminary estimates, lead to the fastest reduction in GHGs (Weidema et al. 2008).

One possible strategy for providing broader support and awareness for organic production among farmers, while retaining control and transparency for policy and civil society, would be to establish so-called “green accounts” for farmers (Eionet, 2010).12 Evaluations of such input-output accounting systems, developed to facilitate voluntary improvements in farm environmental performance in countries with intensive agricultural production, show that, in a broad spectrum of different agricultural operations and enterprises, they often lead to improvement in nutrient and energy efficiency with no extra cost to farmers (Halberg et al. 2005).

With respect to food waste, one policy option would be to eliminate legal barriers and disproportionate food-safety standards that lead to high waste rates. Hence, food-safety standards—many introduced in the context of the mad cow-disease crisis—should be thoroughly reviewed (Verburg, 2010). In particular, the actual meaning of “eat-by dates” should be better communicated to consumers to avoid wasting food, without, of course, compromising their lives and health.

In addition, given the research evidence on the effectiveness of food advertising for fatty, salty, and sugary snacks and drinks (especially among children and the poorly educated), regulation, particularly during children’s programs, should be considered as a means to limit exposure to such communications. Although voluntary agreements are one option here (Forum for Fødevarereklamer, 2008; 2009), national regulatory bodies should have monitoring and sanctioning tools in place to ensure that such agreements are maintained.

Self-Commitment Instruments, Public Procurement, and “Nudging”

Today, a growing number of food retailers and producers want to participate in this interesting high-margin market for sustainable products, and even highly price-oriented discount retail markets have begun active promotional programs for sustainable products (Tukker et al. 2009). Public procurement of organic food has also become an appealing instrument for increasing sales of organic products in many (western) European countries, one promoting the idea that the public sector can be a role model as well as an opportunity for achieving economies of scale (Mikkelsen et al. 2006). Such public procurement serves a triple function: it supports organic farming, it can increase the acceptability of and preferences for organic food among cafeteria users via frequent exposure and habit formation, and it can help improve public health. Nevertheless, this distribution channel remains far below its potential (Lorek et al. 2008). Most particularly, despite the recognized environmental and health impacts of animal products, public procurement policies aimed at reducing meat consumption in public dining facilities are rare. The most prominent approach is a weekly “veggie day” that promotes vegetarian dishes.13 However, such choice restriction can trigger backlash and might be ineffective in the longer run.

To induce a shift toward healthier diets and lifestyles, behavioral economics-informed consumer policy has suggested and applied a toolbox of “nudges” that softly and voluntarily shift consumers toward “better choices” (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008; OECD, 2010a). Examples include efforts to create a health-supportive infrastructure, sustainable choice defaults (e.g., in public dining facilities), and access to affordable, healthier alternatives for all income groups (Wahlen et al. 2012; Reisch & Gwozdz, 2013), such as requiring students to pay cash for sweets while presenting healthier options more attractively. Such solutions lead to higher participation than simply banning junk food or sugar-sweetened beverages from school cafeterias (Downs et al. 2009; Just & Wansink, 2009; Taber et al. 2012).

A Final Thought

The production of good policy requires both policy-minded researchers and research-minded policy makers (Bogenschneider & Corbett, 2010), which is all the more important in the food domain where drafting effective policies to foster sustainable food consumption requires an understanding of the entire food system and all its interactions and dependencies. Its opposite, the tendency to view single aspects of sustainability as unrelated—to dissociate food production from nutritional behavior, economic aspects from social aspects, health aspects from environmental aspects, and everyday meal planning from other life areas like employment, housework, and leisure—is responsible for the limited success of many approaches tried so far (Eberle et al. 2006). A first priority, therefore, is to develop integrative, cross-sectoral, population-wide policies that address such issues as agriculture and food supply, availability and access to food, physical activity, welfare and social benefits, fiscal policies, and information and marketing, all important elements discussed in this article.

Notes

1 This article builds on three discussion papers prepared for the “Policy Meets Research” workshops on sustainable food consumption within the CORPUS consortium (see http://www.scp-knowledge.eu) held at the Lebensministerium in Vienna in 2010/11. Also drafted for these workshops and available on the CORPUS website are the so-called “knowledge units,” highly condensed policy briefs offering succinct overviews on such topics as a definition of “sustainable food consumption,” “hot spots” of sustainable food consumption, sustainable food systems, food waste, food and GHG emissions, and obesity as sustainable consumption issues.

2 Unless otherwise noted, “European Union” and “EU” refers to the group of EU-27 member states.

3 See http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/sectors/food/eu-market/index _en.htm.

4 “Small and medium-sized enterprises” (SMEs) are defined by EU law (EU recommendation 2003/361) primarily in terms of number of employees (< 250) and either annual turnover (= €50 million [US$67.5 million]) or balance sheet total (= €43 million [US$58 million]).

5 The EU-15 encompasses Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

6 The EU-25 includes Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

7 See http://www.netregs.org.uk/business_sectors/food__drink_processing.aspx.

8 Virtual water is the same as a product’s water footprint (Hoekstra et al. 2011). It includes all water used, contaminated, or evaporated during the production process—the so called green, blue, and grey water (WWF, 2009; Hoekstra et al. 2011).

9 See http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui.

10 For instance, recent research has suggested that organic meat production may give rise to higher GHG emissions than conventional meat production (Kool et al. 2009), while the German Öko-Institut has claimed that apples grown in Germany may have a higher carbon footprint than apples imported from New Zealand (Grießhammer & Hochfeld, 2009).

11 For a summary of the original proposals, see http://www.euractiv.com/en/cap/sweden-promotes-climate-friendly-food-choices/article-183349.

12 In Denmark, “green accounts” are part of a mandatory environmental reporting system that accounts for the physical flows of pollutants and resource efficiency.

13 See, for instance, a recent Finnish campaign along these lines described at http://www.valitsevege.fi/node/2.

©2013 Reisch et al.

Note: The entire Summer 2013 issue of the SSPP Journal is focused on sustainable food consumption. To read the entire issue, click

here.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Lucia Reisch is with the Copenhagen Business School, Porcelaenshaven 18a , Frederiksberg, 2000 Denmark (email: lr.ikl@cbs.dk)

Ulrike Eberle is with CORSUS, Nernstweg 32-34, Hamburg, 22765 Germany (email: u.eberle@corsus.de)

Sylvia Lorek is with the Sustainable Europe Research Institute, Schwimmbadstr 2e, Overath, 51491 Germany (email: sylvia.lorek@t-online.de)

|