1. Introduction

By analogy of the remark of J. R. Seeley (1919), it can be emphasized that:

Humanity without humanization has no fruit;

Humanization without humanity has no root.

Just as “history without human and human without history are pointless” (Mshvenieradze, 1985), similarly “humanity without humanization and humanization without humanity are pointless” (Konar and Chakrabortty, 2011).

M. M. Prishvin, in The Road to a Friend: Diaries (1982), has differentiated the means of naturalization from the means of humanization as follows:

Arts and science – are doors, as it were, from the world of nature into the human world: Nature enters into the world of man through the door of science, and man enters nature through the door of art and then recognizes himself and call nature his mother.

In praise of human reason, science and technology, Maxim Gorky (1868-1936 A.D), wrote:

In nature there is nothing more miraculous than the human brain, more amazing than the process of thinking, more precious than the fruits of scientific research (See Borisov, 1986).

The intrinsic implication of Gorky’s remark is that humanization cannot be decoupled from humanity (Konar and Chakrabortty, 2011).

Both the concepts of humanization of nature and naturalization of human were disclosed by Karl Marx in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (Marx, 1975).

In The Humanization of the Cosmos – To What End?, Peter Dickens (2010) has argued that “Since the Renaissance period of the sixteenth century, the word ‘humanization’ has been used to connote something beneficial, especially to human beings. As we will now see, humanizing the cosmos is regarded in just these terms by some influential proponents of space travel and space colonization”. In Dickens’s (2010) article, humanization has been iteratively substituted with “colonization”, “globalization” and “commercialization”. He emphasizes that humanization has both positive (beneficial) and negative (harmful) effects. “Cosmists argued that a form of cosmic humanization was central to developing the next major stage of human evolution” (Dickens, 2010).

Socialization and humanization are interchangeably used (See Giddens, 1994; Mshvenieradze, 1985). In naïve sense, humanization means what human does to the nature or natural order of things irrespective of normative considerations or value judgments. In better words, the intrusion of human action or activity into the nature or natural order of things is called humanization irrespective of whether such intrusive human action or activity is ethically or morally good or bad. In sophisticated sense, humanization or socialization can be defined as the deliberate, conscious and purposive intrusion of human action or activity into the vast natural order of things, including earth, inner space and outer space in the infinite universe irrespective of value judgments.

The appearance and evolution of human marked the beginning of the process of socialization. Historically, world’s development, backed up by the scientific and technological revolution, has greatly intensified the process of socialization so that virtually all facets of the globe have felt human touch. The face of the earth has been radically transformed within the lifetime of a single generation owing to the unprecedented momentum of socialization.

Throughout the brief history of human, socialization has affected the nature in ways and to an extent not previously thought possible. There is probably no currently possible position of socialization, which could threaten the existence of life on this planet. Hence, we should start planning explicitly for “sustainability”, for perhaps the first time in history.

Sustainability (or unsustainability) means ecologically social sustainability (or unsustainability) or ecologically sustainable (or unsustainable) social stability (or instability), where the term "social" consists of multitude of "sub-socials" such as communicative, corrupt, criminal, cultural, economic, ethical, familial, gender, legal, marital, military, moral, philosophical, political, private, psychological, public, religious, ritual, scientific, sexual, spiritual, technological, terrorist, etc.

In short, under the ceteris paribus assumption, sustainability (or unsustainability) indicates the coexistence of ecological stability (or instability) and social stability (or instability). The ceteris paribus assumption implies that the natural instability indicated by natural catastrophes and natural stability indicated by persistent equilibrium of various natural life support systems are exogenously and spontaneously determined (Konar and Modak, 2010; Konar and Chakrabortty, 2011; Konar, 2012).

While the indicators of ecological instability can be encapsulated in the depletion, degradation and/or destruction of "ecological resources", the indicators of social instability can be reduced to the depletion, degradation and/or destruction of "social resources", which includes various "sub-social resources".

Thinking about a sustainable world is pointless, unless an adequate, appropriate or apposite “way” can be discovered to get there. The nature of sustainable world can be imagined easily, but whether and how human population can continue to survive indefinitely on this “tiny little islet of life amid the boundless ocean of lifelessness” (Rebrov, 1989) without threatening the survival of all other biological populations, may not be so easy.

Since the concept “social” consists of various “sub-socials”, so socialization implies “ization” of various “sub-socials” (e.g. politicization, economization, moralization, militarization, spiritualization, etc.).

Hence, on the basis of certain conceptions, diagrams, notations and their notions, this article discloses how socialization can generate sustainability, unsustainability and neither sustainability nor unsustainability. The latter may be renamed as meta-sustainability or meta-unsuatainability.

2. Features of Socialization

The humanization of nature is derived from the need to put an end to man’s perplexity and helplessness in the face of its dreaded forces, to get into a relation with them, and finally to influence them (Freud, 1927/1928).

Socialization has the following features:

(1) Socialization may be undertaken by (i) an individual human, (ii) a group/community of humans and/or (iii) the different groups/communities of humans independently, collaboratively, collectively, simultaneously and/or successively.

(2) The mode of socialization is determined by the nature of culture. Our social world is stuffed with innumerable cultures. But in our epoch, social world’s dominant culture is capitalist in nature. The effective life of our epoch started since the beginning of the industrial revolution in the 1760s. Hence, socialization is being induced/influenced by the capitalist principles and practices.

(3) Human community/society is composed of innumerable humans. In consequence, socialization is the sum-product of numberless human actions or activities undertaken/executed to the nature or natural order of things.

(4) We are conscious of two different worlds: natural world and social/human world. Social world is the eventual and inevitable outcome of socialization of the nature or natural world, past and present.

(5) Socialization is backed up by consciousness, not by blind instinct. Consciousness is the highest and purely human form of reflection. It arose with the emergence of humans and the human society, and cannot exist outside that society. Consciousness is awareness, which indicates knowledge of what is going on around the world (Krapivin, 1987). “Our consciousness has a form and content with certain historical character, and to the historical consciousness there consequently belongs a collective inheritance which we carry with us, whether or not we want to” (Olsen, 2010).

(6) Life is continuous and hence, the process of socialization follows suit. No single process of socialization stands by itself. Every process of socialization is the consequence of an endless chain of various processes of socialization extending into the past. In better words, every process of socialization is a point in the seamless continuity of space-time.

(7) The following seven elements are congealed in the process of socialization:

(i) The subject or actor of socialization

(ii) The object or end of socialization

(iii) The need for socialization

(iv) The motives for socialization

(v) The means of socialization

(vi) The product or result of socialization

(vii) The conditions of socialization

Both ends and means are predominantly influenced by the cultural complex. The value system governing a community/society determines the conception of the ends and prescribes the modes of socialization for reaching the ends.

(8) A frame of reference is necessary to conceptualize socialization. Such frame of reference includes (Pinney, 1940):

(i) The statistical description of the community/society of which the individual actor is a part resulting in a roughly ideal type.

(ii) The system of values to which the community/society adheres.

(iii) The derivative standards governing the “modes of socialization” used to achieve the ends.

(iv) The availability of technology for its usage.

But it is noteworthy that a frame of reference is subject to change.

(9) Socialization is a stage-oriented phenomenon in the sense that it passes/moves through the following successive stages:

(i) Socialization by primitive society

(ii) Socialization by agricultural society

(iii) Socialization by partially industrialized society

(iv) Socialization by advanced industrialized society

(v) Socialization by globalized/globalizing society

(vi) Socialization by instantaneously electronic communicative society

(vii) Socialization by cosmopolitan society

The foregoing stages of socialization can be substituted with another set/series of stages of socialization.

(10) Each stage of socialization is coupled with the corresponding stage of sustainability. Hence, we can have the following seven stages of sustainability:

(i) Sustainability of primitive society

(ii) Sustainability of agricultural society

(iii) Sustainability of partially industrialized society

(iv) Sustainability of advanced industrialized society

(v) Sustainability of globalized/globalizing society

(vi) Sustainability of instantaneously electronic communicative society

(vii) Sustainability of cosmopolitan society

(11) One of the crucial criteria, by which human ranks highest in the scale of species, is socialization.

(12) Socialization is both a “matter of degree” and a “matter of order”. Deforestation or reforestation, for example, can be brought about at any rate (e.g. 25%, 50%, 75%, etc.). The rate at which such deforestation or reforestation occurs, is called the “degree” of socialization. This is an example of the “matter of degree” of socialization. The phenomenon of the “matter of order” of socialization will be obvious from the following example: firstly, a certain part of wild forest is destroyed; secondly, that deforested land is used for agriculture; thirdly, agriculture is substituted with sericulture; fourthly, sericulture is substituted with floriculture; fifthly, floriculture is substituted with pisciculture. Thus the same part of the wild forest is transformed successively to satisfy the changing human purposes over time. Such successive transformations are called the “first order socialization”, “second order socialization”, “third order socialization”, and so on.

(13) Socialization is a fundamental criterion for ranking groups of people, called “races”. “A race is properly a biological group, not an accidental, political or linguistic assembling of individuals, a group possessing in common a certain hereditary type” (Closson, 1895-1896). While no such group of people can have remained without intermixture, it is possible to distinguish the principal human races and to classify existing individuals as representing more or less accurately the pure type of one or another race. The still persistent primitive peoples in the name of traditional or tribal peoples have never attained the “higher stage of socialization”, at which peoples become inclined to subjugate the wild nature. Hence, such peoples have themselves remained savage.

(14) Socialization/humanization means “human action” undertaken to the nature. But “action” is determined by “decision”, which is determined by “choice among the alternative values”, which is determined by “deliberation”, which is determined by “knowledge”. But knowledge determines the “status of our understanding”, which acts as the “beginning of our freedom”, which consists in being “masters of our own fates” (Lipson, 1973). We cannot undertake or execute action or activity without understanding. Though expansion of knowledge augments our understanding, yet it does not always enlarge our “capacity for action”. This holds true for the zone of nature or universe, which absolutely resists socialization (e.g. sun, the extremely outer space).

(15) On the basis of the degree of socialization, the nature or universe can be classified into three zones:

(i) Zone of perfect socialization

(ii) Zone of quasi-socialization

(iii) Zone of perfect non-socialization

There is an analogy between socialization and mathematization. On the basis of the degree of mathematization, all academic disciplines can be classified into three groups:

(i) Disciplinary group of perfect mathematization (e.g. physics, chemistry, astronomy)

(ii)Disciplinary group of semi or quasi mathematization (e.g. economics, commerce, management)

(iii) Disciplinary group of perfect non-mathematization (e.g. literature)

(16) Socialization creates result, which may be positive (or beneficial) or negative (or harmful). Thus depending upon the nature of the result realized from socialization, it can be divided into “positive socialization” (PS) and “negative socialization” (NS). Socialization is positive, if it yields benefit, or if its result is beneficial, and negative, if it inflicts cost, or if its result is harmful to The Great Chain of Being (1936) of A. O. Lovejoy (See Cuddon, 1998). Reforestation and deforestation, respectively, are the examples of positive socialization and negative socialization of the forest facet of the globe. The difference between the positive socialization and the negative socialization gives rise to the “balance of socialization” (BOS). Symbolically, BOS = [PS – NS].

(17) Earlier, we have pointed out that “human action” is determined by “decision”, that is why “action” is renamed as “decisionized action”. It means that action is undertaken/executed by the decision-making unit, decision-maker or actor.

But most of the decisionized actions are rational, as opposed to irrational. On the contrary, one study claims that “[M]ost decision-making is only partly rational, and is influenced at least as much by uncalculated emotional commitments and unexamined assumptions” (Clayton and Radcliffe, 1996).

In ordinary sense, rational decision is based on reason rather than on emotion. But in the present context, we assume that rational decision-making unit seeks to “optimize” self-interest, which means to maximize benefit (or gain) and/or to minimize cost (or loss) subject to some “constraints”. That is why a “rational decision-maker” is treated as “constrained self-interest optimizer”.

It is worthy to note that self-interest precludes neither selfishness nor altruism. In other words, self-interest may be selfish or altruistic. Further, self-interest may be of two types: “enlightened self-interest” and “destructive self-interest”. Alex Des Tocqueville in his classic book Democracy in America of the early 1800s referred to it as “self-interest rightly understood” in the sense that “caring for others is as important for those who care as for those who are cared for” (See Ikerd, 2011).

(18) During the process of socialization, decision-makers can create external advantage and external disadvantage for the nature and human society. While the “external advantage or better-off” is called “positive externality”, the “external disadvantage or worse-off” is called “negative externality”. As optimization implies maximization and/or minimization, similarly externality refers to positive externality and/or negative externality.

When the action of a decision-maker creates benefit for the nature and human society, for which the decision-maker is not paid, or given any return or reward, there occurs a positive externality for the nature and human society. On the contrary, when the action of a decision-maker creates cost for the nature and human society, for which the decision-maker does not pay, or give any compensation, there occurs a negative externality for the nature and human society.

If a honey producer expands its beehives, the production of oranges of the owners of near-by orange groves increases, since bees help pollinates oranges. This is an example of positive externality created by the honey producer for the orange producers. On the contrary, pollution of a lake by an insecticide-manufacturing firm reduces the fish population in the lake owned by a fish-producing firm. This is an example of negative externality created by the insecticide-manufacturing firm for the fish-producing firm. Noteworthy that externalities occur in both production and consumption of goods and services.

Rob Dietz (2012) has argued that “Here’s is crazy but true fact: negative externalities are the norm – not the exception – in our current economic setup. Failure to recognize this fact has created a wild divergence between theory and practice when it comes to managing harm caused by economic activity”(Dietz, 2012).

(19) The most important type of socialization, which can lead to the origin of sustainability, unsustainablity and meta-(un)sustainability, is “autonomous socialization”.

Socialization based on, or backed up by the “principle of self-interest optimization” of a decision-making unit, is defined as “autonomous socialization”, whose index is denoted by ATS. It is of two types such as “positive autonomous socialization” and “negative autonomous socialization”. The essential distinction between them is that while the former creates positive externality, the latter creates negative externality. Let us suppose that PATS is the index of “positive autonomous socialization”, while NATS is the index of “negative autonomous socialization”.

The difference between PATS and NATS gives rise to the “balance of autonomous socialization”, whose index is denoted by BOATS. Symbolically, BOATS = [PATS – NATS], which will be positive, negative, or equal to zero depending upon whether PATS is greater than, less than, or equal to NATS.

There are as many BOATSs as there are individual decision-makers in the society/community. The summation of all the BOATSs gives rise to the “aggregate balance of autonomous socialization”, whose index is denoted by ABOATS.

Similarly, the index of “aggregate positive autonomous socialization” and the index of “aggregate negative autonomous socialization” are respectively denoted by APATS and ANATS.

In the context of autonomous socialization, it may be relevant to recall the remarks of Fyodor M. Dostoyevsky (1956) and Georgi Plekhanov (1976):

“Man needs but one independent desire no matter how much that independence costs or where it leads” (Dostoyevsky, 1956).

“Interest is the source, the prime mover of any social creativity” (Plekhanov, 1976).

(20) “Negative autonomous socialization” is synonymous with “tyrannical small decision” (See Kahn, 1966; Odum, 1982), while the “positive autonomous socialization” is synonymous with the “benevolent small decision”. The following two examples of the tyrannical small decision or negative autonomous socialization may be relevant (Odum and Barrett, 2006):

“Increasing the height of smokestacks – a quick fix for local smoke pollution – is one example in which many such ‘small decisions’ lead to the larger problem of increased regional air pollution” (Kahn, 1966).

No one purposefully planned to destroy 50 per cent of the wetlands along the northeastern coast of the United States between 1950 and 1970, but it happened as a result of hundreds of small decisions to develop small tracts of marshland. Finally, the state legislatures woke up to the fact that valuable life-support environment was being destroyed, and one by one, each legislature passed wetlands protection acts in an effort to save the remaining wetlands. It is human nature to avoid long-term or large-scale actions until there is a threat that is perceived by a majority of the population (Odum, 1982).

3. Further Classifications of Autonomous Socialization

Autonomous socialization can be classified into (i) cultural autonomous socialization, (ii) myopic autonomous socialization, (iii) demonstrative autonomous socialization, (iv) imitative autonomous socialization, and (v) market induced autonomous socialization, which can be discussed successively as follows:

3.1. Cultural Autonomous Socialization

The ways of socialization of the nature shape the ways of understanding it. But this is just one side of a dual process. The ways, in which people understand their nature, also shape how they socialize the nature. Cultural perspectives thus provide the knowledge, assumptions, values, goals and rationales, which guide the mode/nature of socialization. This socialization, in turn, yields experiences and perceptions, which shape people’s understanding of the natural world. The process is not unidirectional, but dialectical (Milton, 1997). Cultural autonomous socialization may be positive and negative.

3.2. Myopic Autonomous Socialization

By the principle of structuralism, the opposite polarity of “myopia” or “myopic” is “hyperopia” or “hyperopic”.

On the basis of the relative weighting of the present and the future, Dresch (1990) has differentiated “myopia” (the preference of the present relative to the future) from “emmetropia” (the correct relative weighting of the present and the future) and “hypermetropia” (the preference of the future relative to the present).

Myopia is the inability to see things properly, when they are far away, because there is something wrong with one’s eyes. If we describe the behavior, activity or action of an individual as myopic, we are critical of it, because the individual is unable to realize that his/her behavior, activity or action can create “negative consequences” for nature and human society. Thus in almost all cases, myopic autonomous socialization is “negative in nature” in the sense that it creates “negative externality” for the nature and human society.

Myopic autonomous socialization is based on the “conjecture” that if a decision-maker undertakes a particular type of action or activity, other decision-makers will not follow suit. It means that myopic autonomous socialization ignores the reactions of other decision-makers in the society/community. There are two reasons behind such conjecture:

(i) The decision-maker thinks/assumes that if he/she undertakes a particular type of action, his/her own benefit will increase. But since he/she is only one of the many decision-makers in the society/community, so if he/she undertakes such type of action, the increase in his/her benefit will produce loss of benefit, which will be distributed more or less equally over all other decision-makers, so that each one of them will suffer a negligible loss, which will not be sufficient to induce them to change their own previous actions.

(ii) The decision-maker thinks/assumes that if he/she undertakes a particular type of action, the impact of his/her own action on the vast natural order of things will be too little to measure/perceive. That is why Wagner (2011) has argued that: “You are one of seven billion people on Earth. Whatever you or I do personally….the planet doesn’t notice”.

But the paradox is that if all the decision-makers undertake the same/similar action simultaneously and independently of others, though individual decision-maker’s share in such action (i.e. micro-level socialization) decreases, the aggregate volume of action (i.e. macro-level socialization) increases.

The most important feature of myopic behavior or action is that the individual decision-makers do not learn from past experiences (that is, past miscalculations of the reactions of other decision-makers) in the sense that they do not realize that other decision-makers may act identically, independently and simultaneously. When, for example, Mr. A casts the plastic bags/packets/sachets into here and there, he does not realize that Mr. B, Mrs. C……..Mrs. Z may do the same activity, and in consequence, their simultaneous impact on the environmental status. Though the expected reaction of other decision-makers does not in fact materialize, the decision-makers continue to conjecture that the initial conjecture holds, that is, each expects the others to remain at a given position of action. Thus the behavior or action of myopic decision-makers is treated as at least naïve (if not stupid), as opposed to sophisticated.

3.3. Demonstrative Autonomous Socialization

It is undertaken by the decision-makers only to demonstrate/exhibit their uniqueness, non-comparability and conspicuousness about socialization in the society/community. It may also be positive or negative.

3.4. Imitative Autonomous Socialization

This type of socialization, which may be positive or negative, occurs when one’s action is copied by other decision-makers.

3.5. Market Induced Autonomous Socialization

The excess demand for or excess supply of goods and/or services in the markets can induce the decision-makers (e.g. producers and/or consumers) to undertake action to adjust the volume of production and consumption of those goods and services, irrespective of their social and/or ecological desirability. In consequence, market induced macro-level autonomous socialization, which may be positive or negative, increases or decreases.

4. Role of Autonomous Socialization in the Origin of Sustainability, Unsustainability and Meta-(Un)Sustainability

The equality and inequality between APATS and ANATS lead to the following results:

(i) If APATS = ANATS, then ABOATS = 0, which brings about meta-(un)sustainability or neither sustainability nor unsustainability.

(ii) If APATS > ANATS, then ABOATS > 0, which creates sustainability.

(iii) If APATS < ANATS, then ABOATS < 0, which generates unsustainability.

5. Secular Correlation between APATS and ANATS

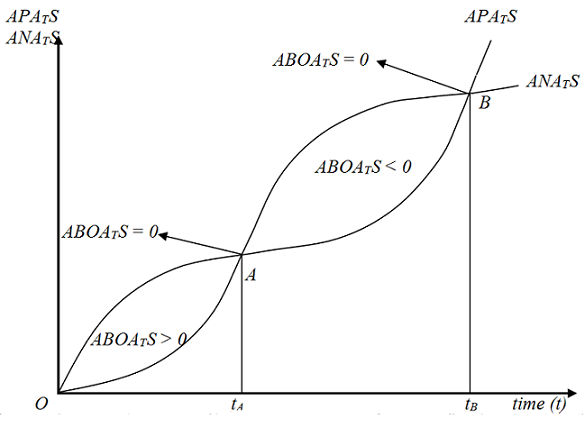

The secular interrelationship between APATS and ANATS can be represented in terms of Figure 1. The ANATS curve assumes the elongated–S shaped, while the APATS curve assumes its inverse shape. In Figure 1, APATS and ANATS are measured along the vertical axis, while time (t) is measured along the horizontal axis.

The following results can be obtained from Figure 1.

(i) The first three stages of socialization by primitive society, agricultural society and partially industrialized society can be put successively within the time span OtA. All these societies enjoy sustainability within such time span, since APATS > ANATS, or ABOATS > 0.

(ii) At the points A and B, APATS = ANATS and hence ABOATS = 0, which indicates meta-(un)sustainability or neither sustainability nor unsustainability.

(iii) Within the time span tAtB, the next three societies such as advanced industrialized society, globalized/globalizing society and instantaneously

electronic communicative society can be put successively. They go through unsustainability, since APATS < ANATS, or ABOATS < 0 within the time span tAtB.

(iv) While the point A shows low level of aggregate autonomous socialization, the point B indicates higher level of aggregate autonomous socialization (AATS), though they both are meta-(un)sustainable.

(v) The instantaneously electronic communicative society, which is still unsustainable, can cross the meta-(un)sustainability point B, if such society can acquire “accommodating socialization” (ACS)[See Section 7].

(vi) Since at present, the instantaneously electronic communicative society is still surviving at an unsustainable point within the time span tAtB, so the necessity of ACS [See Section 7] is inevitable to lead the society to move forward crossing the meta-(un)sustainable point B to realize/restore sustainability. This is only possible, if the cosmopolitan society is substituted for the instantaneously electronic communicative society beyond the meta-(un)sustainable point B.

(vii) Since we can neither return to any of the earlier societies from the instantaneously electronic communicative society, whose position can be indicated by any point nearer to the point B within the time span tAtB, nor live unsustainably at the same point, so the only alternative path open to us is to induce/inspire the society to adopt such adequate policies, principles, precautions, and/or practices so that APATS becomes stronger than ANATS, which is only possible beyond the meta-(un)sustainable point B.

Figure 1

6. (Un)Sustainability by Cost-Benefit of Socialization

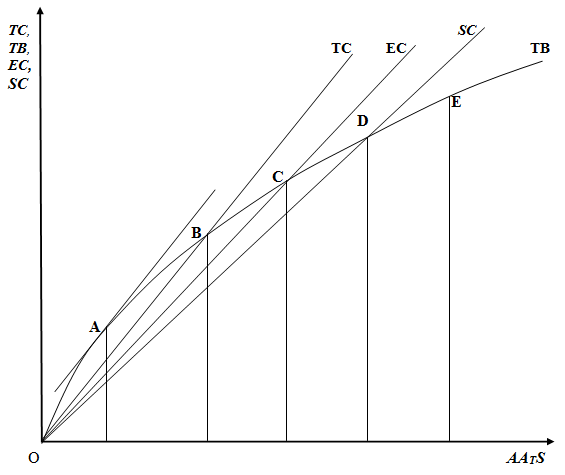

The “aggregate autonomous socialization” (AATS) includes both APATS and ANATS. While the APATS creates benefit, the ANATS inflicts cost to the human society. The following composition of the cost and benefit derived from the AATS is as follows:

(a) Total benefit (TB) = [ecological benefit (EB) + social benefit (SB)]

(b) Total cost (TC) = [ecological cost (EC) + social cost (SC)].

(c) All costs are assumed to be the linear function of the AATS.

(d) The TB is assumed to obey the “diminishing marginal benefit principle”, which implies that as AATS increases, TB also increases, but at the diminishing rate.

(e) The EC is assumed to be greater than the SC that is why, EC line lies above the SC line. But the main inference remains unaffected, even if SC is greater than EC.

Now on basis of the foregoing five assumptions and Figure 2, we can realize the following multiple notions of sustainability and unsustainability. In Figure 2, TB, TC, EC and SC are measured along the vertical axis, while AATS is measured along the horizontal axis.

(i) Point A implies supernormal sustainability (that is, ecological sustainability is coupled with social sustainability), where TB >TC and net benefit [TB – TC] is maximum.

(ii) Point B implies meta-(un)sustainability or neither sustainability nor unsustainability, where TB = TC and net benefit = 0.

(iii) Point C implies normal unsustainability (that is, ecological sustainability is coupled with social unsustainability), where TC >TB and net cost [TC-TB] = SC > 0.

(iv) Point D implies supernormal unsustainability (that is, social unsustainability coupled with ecological unsustainability is below the critical point), where TC >TB and net cost = [SC + some portion of EC].

(v) Point E implies critical unsustainability (that is, the social and ecological unsustainability exceeds the critical point), where TC >TB and net cost = [SC + larger portion of EC].

Thus Figure 2 indicates that point A is the optimal point of AATS, while the points B, C, D and E are sub-optimal points of AATS and their degree of sub-optimality increases as we move from the point B to the point E in the rightward direction along the TB curve.

Figure 2

7. Cures of Unsustainability or Restoration of Sustainability

How unsustainability can be reduced/ruled out, or how sustainability can be restored/realized through the adjustment of ABOATS or APATS and ANATS – is the most vital question. This can be done only by means of accommodating socialization, whose index is denoted by ACS. Accommodating socialization is needed only to rule out the inequality: APATS < ANATS, or ABOATS < 0.This means that the sole objective of ACS is to bring about (i) APATS = ANATS, or ABOATS = 0 or (ii) APATS > ANATS, or ABOATS > 0. Hence, accommodating socialization is positive or beneficial in nature.

Sustainability is a macro or global phenomenon. So accommodating socialization should be influenced/introduced by macro actors (e.g. national governments, international organizations, NGOs, etc.).

The ABOATS may be applicable to local, national or global community/society. It is also applicable to a given period of time, which may be renamed as planning period.

The outcome of the ABOATS depends on many atomistic decisions about the autonomous socialization undertaken by many decision-makers in the society/community. That is why there is little reason to expect that the result of these decisions will lead to ABOATS = 0 or ABOATS > 0. If this is not the case, ACS will appear at the end of planning period.

Further, accommodating socialization is also known as realized socialization. For one can realize at the end of the planning period whether or what type of socializations have occurred during that period. In this sense, accommodating socialization is treated as unplanned, as it occurs to rule out the inequality: APATS < ANATS, or ABOATS < 0, which have occurred during the planning period.

8. Concluding Comments

In antiquity, people felt uneasy about natural forces, believing or thinking that nature was filled with gods, giants and heroes (Zeus, Ares, Prometheus, Poseidon, Chronos). In middle ages, there was a fear of perdition, Hell and Purgatory. But in modern times, from the 18th and 19th century to our own century, the things produced by ourselves are more feared than anything else (Olsen, 2010). This has occurred only due to excessive negative autonomous socialization over positive autonomous socialization.

Since the inception of the industrial revolution in the 1760s, the processes of socialization bite more deeply than ever before, affecting the overdeveloped countries of the Northern hemisphere in the globe in particular, but making themselves felt everywhere. In consequence, we find that: “Civilized man had declared war against his own environment, and the battle was raging on all continents, gradually spreading to these distant islands. In fighting nature, man can win every battle except the last. If he should win that too, he will perish , like an embryo cutting its own umbilical cord” (Heyerdahl, 1976).

Owing to unprecedented momentum of socialization, the “natural nature” has been and is still being substituted with the “socialized nature”. Following Anthony Giddens (1994), it can be reiterated that tradition should/can be defended, but not in the traditional way. For “tradition” defended in the “traditional way” becomes fundamentalism. By analogy, “nature” defended in the “natural way” implies natural fundamentalism. Hence, socialization of nature or universe is inevitable, but socialization should be directed in such a way so that the APATS becomes stronger than the ANATS for the realization/restoration of sustainability.

McKibben (1989) offers a lament that nature, as we have come to understand it, is no longer available to us. He emphasizes that there is nowhere that is pristine nature any more. There is nowhere on earth that has not been affected by environmental changes that we have brought. There is going to be literally nowhere on the earth that will remain untouched by human activity. Soon or may be already, there will be no way you can go and say, “Look, the habitat here is undisturbed”, because everywhere has been disturbed by global climate change. In this context, the following remark of McKibben (1989) about the nature of nature is worthy to recall:

An idea, a relationship, can go extinct just like an animal or a plant. The idea in this case is “nature”, the separate and wild province, the world apart from man to which he adapted…In the past we have spoiled and polluted parts of that nature, inflicted environmental “damage”. But that was like stabbing a man with toothpicks: though hurt, annoyed, and degraded, it did not touch vital organs or block the path of the lymph or blood. We never thought that we had wrecked nature. Deep down, we never really thought we could: it was too big and too old………[But now we find we] have produced the carbon dioxide – we have ended nature (McKibben, 1989).

On the contrary, let us see what Giddens (1994) said about the nature:

The paradox is that nature has been embraced only at the point of its disappearance. We live today in a remoulded nature devoid of nature…….. Nature cannot any longer be defended in the natural way……… Socialized nature is by definition no longer natural. The longing for a return to nature is a healthy nostalgia…… Nature has come to an end in a parallel way to tradition……..Instead of being concerned above all with what nature could do to us, we have now to worry about what we have done to nature.

John Muir argues that “The world, we are told, was made for man. A presumption that is totally unsupported by the facts………. Nature’s object in making animals and plants might possibly be the first of all the happiness of each one of them…….. Why ought man to value himself as more than an infinitely small unit of the one great unit of creation” (See Cunningham and Cunningham, 2009).

The remark of Baba Dioum has much value in the present context: “In the end, we conserve only what we love. We will love only what we understand. We will understand only what we are taught” (See Cunningham and Cunningham, 2009).

“The universal law is that others do not exist for us but we for others” (Katscher, 1900-1901).

Though humans are natural and social, yet they are not ecological. But the still persistent primitive humans in the name of tribal or traditional humans are not only natural and social, but also ecological, because no “ecological organism” by its own activities or actions can vitiate the “ecological system”, which maintains its sustainability. The acquisition of ecological colonialism, dominance, hegemony, imperialism, monopoly, and/or supremacy by humans over sublunary species does not designate the humans as “ecological”. The organisms, which vitiate the stability of ecological system, cannot be designated as ecological. Hence, the ecological designation should be dismantled from the humans.

Some authors have described human species as a kind of planetary disease and even comparing it to cancer (McHarg, 1969; Gordon and Suzuki, 1991; Gregg, 1955). Hern (1990) has described the human species as a “malignant epiecopathological process”, which is destroying the global ecosystem.

Mastery over nature means destroying it in the sense that socialized nature is by definition no longer natural. The socializing of nature may render it benign and thus actually permit a harmony with it unavailable before. Mastery can quite often mean caring for nature as much as treating it in a purely instrumental or indifferent fashion (Giddens, 1994).

On the basis of the foregoing remark of Anthony Giddens (1994), it can be reiterated that sustainability can be realized/restored only through encouraging/enhancing the positive autonomous socialization and/or accommodating socialization by the prudent principles and policies of the appropriate national and international authorities/organizations.

All processes of socialization are being undertaken/executed in the framework of capitalism. But some authors have questioned: Is capitalism sustainable? (Martin O’ Connor, 1994), Is sustainable capitalism possible? (James O’ Connor, 1994; Ikerd, 2006).

In his Sustainable Capitalism: A Matter of Common Sense, John Ikerd (2005) has developed an alternative vision for capitalism. Rather than calling for the overthrow of capitalism, he has suggested how capitalism can become a vehicle for fostering a “new economics of sustainability”.

In capitalist and/or democratic societies, it is very difficult to induce, encourage or persuade the atomistic decision-makers to bring about the inequality: APATS > ANATS, or ABOATS > 0 so that sustainability can be realized/restored. But the national governments and international organizations can be entrusted with the task of introducing accommodating socialization for the realization/restoration of sustainability.

“Cosmopolitan society” (Konar and Chakrabortty, 2011) may enjoy sustainability by the excessive positive autonomous socialization and accommodating socialization.

References

Borisov, V. (1986). Militarism and science. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Clayton, A. M. H. and Radcliffe, N. J. (1996). Sustainability. London: Earthscan.

Closson, C. C. (1895-1896). Social selection. Journal of Political Economy, 4, 449-466.

Cuddon, J. A. (1998). The penguin dictionary of literary terms and literary theory. London: Penguin.

Cunningham, W. P. and Cunningham, M. A. (2009). Principles of environmental science. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill.

Dickens, P. (2010). The humanization of the cosmos – To what end? Monthly Review, Volume 62, Issue 6 (November).

Dietz, R. (2012). Negative externalities are the norm. Mother Pelican: A Journal of Sustainable Human Development, Volume 8, Number 7 (July).

Dostoyevsky, F. M. (1956). Notes from the underground. Collected Works in 10 Volumes, Vol. 4, Moscow: Khudozhestvennaya.

Dresch, S. P. (1990). Myopia, emmetropia or hypermetropia? Competitive markets and intertemporal efficiency in the utilization of exhaustible resources. Resources Policy, 16(2), 82-94.

Freud, S. (1927/1928). The future of an illusion. London: Hogarth Press (Translated by W. D. Robson-Scott and J. Strachey).

Giddens, A. (1994). Beyond left and right. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gordon, A. and Suzuki, D. (1991), It is a matter of survival. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gregg, A. (1955). A medical aspect of the population problem. Science, 121, 681-682.

Hern, W. M. (1990). Why are there so many of us? Description and diagnosis of a planetary ecopathological process. Population Environment, 12, 9-39.

Heyerdahl, T. (1976). Fatu-Hiva: Back to nature. England: Penguin.

Ikerd, J. (2005). Sustainable capitalism: A matter of common sense. Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press (http://www.kpbooks.com).

Ikerd, J. (2006). Is sustainable capitalism possible?. Also available here.

Ikerd, J. (2011). Authentic sustainability: Beyond going green. Also available here.

Kahn, A. E.(1966). The tyranny of small decisions: Market failures, imperfections, and the limits of economics”. Kyklos, 19, 23-47.

Katscher, L. (1900-1901). A bibliographical discovery in political economy. Journal of Political Economy, 9, 423-436.

Konar, A. K. (2012), Defamiliarizing the demographic doomsday diagram. Mother Pelican: A Journal of Sustainable Human Development, Vol. 8, No. 2 (February).

Konar, A. K. and Chakrabortty, J. (2011). Substantive signification of sustainability. Mother Pelican: A Journal of Sustainable Human Development, Vol. 7, No. 8 (August).

Konar, A. K., and Modak, B. K. (2010). Socializing snake society: An Indian instance. Social Change, 40(2), 157-174.

Krapivin, V. (1987). What is dialectical materialism? Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Lipson, L. (1973). The great issues of politics. Bombay: Jaico Publishing House.

Marx, K. (1975). Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844, in Marx, K. and Engels, F. Collected Works, Volume 3. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

McHarg, I. (1969), Design with nature. Garden City, New York: Doubleday/Natural History Press.

McKibben, B. (1989). The end of nature. New York: Random House.

Milton, K. (1997). Ecologies: Anthropology, culture and the environment. International Social Science Journal, 49(4), 477-495.

Mshvenieradze, V.(1985). Political reality and political consciousness. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

O’ Connor, J.(1994). Is sustainable capitalism possible?, in O’ Connor, M. (Ed.), Is capitalism sustainable?. New York: Guilford Press.

O’ Connor, M. (Ed.)(1994). Is capitalism sustainable? New York: Guilford Press.

Odum, W. E. (1982). Environmental degradation and the tyranny of small decisions. Bio Science, 32, 728-729.

Odum, E. P., and Barrett, G. W. (2006). Fundamentals of ecology. Bangalore: Thomson Brooks / Cole.

Olsen, T. O. (2010). On humanization of life. Cultura: International Journal of Philosophy of Culture and Axiology, 8(2), 148-163.

Pinney, H. (1940). The institutional man. Journal of Political Economy, 48(1), 543-562.

Plekhanov, G. (1976). The materialist understanding of history. Selected Philosophical Works in 5 Volumes, Vol. 2, Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Rebrov, M. (1989). Save our earth (Translated by Anatoli Rosenzweig). Moscow: Mir Publishers.

Seeley, J. R. (1919). Introduction to Political Science. London: Macmillan.

Wagner, G. (2011). But will the planet notice?: How smart economics can save the world. New York: Hill and Wang.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Arup Kanti Konar is Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, Achhruram Memorial College, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Jhalda, Purulia, West Bengal, India-723 202. E-mail: akkonar@gmail.com