Introduction

1) Economic growth zones

a) What are they?

It can be said that economic growth zones are special areas or regions or places dedicated to the promotion of economic growth only; and that traditional sweatshops are the extreme version of the economic growth zones established as places where economic growth can be maximized as the social and environmental limits to growth are made minimal or non-existent for the model to work best. They can be export oriented or import-export oriented or import oriented; they are treated in terms of laws/regulations/taxes different than other areas of the same country/region/ community (ILO 2003; Milberg and Amengual 2008); they exist with the goal of encouraging economic growth and of attracting big investors especially foreign investors willing to locate there (WB 2008b); and they are associated with the economic miracle taking place in places such as China (Zeng 2011).

As a consequence of this special economic only purpose, economic growth zones and traditional sweatshops have been associated with the creation of races to the social bottom (extreme poverty/deep social degradation) and environmental bottom (extreme pollution/environmental degradation) within and between countries everywhere in the world where they are at work. Given a choice, sweatshops will be located in the community within a country or in the country with the lowest social and environmental cost. To compete, other communities in the country and other countries will see an incentive in offering lowest social and environmental costs to be able to attract investment and jobs, and this process is the one called social and environmental race to the bottom.

The process in which stakeholders see an incentive in lowering social, economic, and environmental standards to attract market activities, locally and/or internationally, in the case of sweatshops, economic activity, is called a race to the bottom. Hence, special economic zones/traditional sweatshops have two types of negative impacts: a) an internal impact or direct impact on social and environmental and economic conditions within its boundaries; and b) an external or indirect impact when inducing the migration or relocation of production, labour, and pollution, and affecting regulatory standards outside its boundaries. Races to the bottom are so

real that a global regulatory standard containing 12 regulatory and policing items aimed specifically at avoiding races to the bottom in social and economic standards in international business (OECD 2009) or to correct current market flaws (Dinmore and Atkins 2009) is being proposed right now. David Cameron, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, recently pointed out that global standards for the governance of growth should be designed to be effective in ways that avoid creating races to the bottom or environments where the lowest common denominator is the rule (Cameron 2011).

b) Supporters and critics

The supporters or proponents of economic growth zones and traditional sweatshops are pure economic agents/capitalist and traditional academics and individuals under the notion that these zones and sweatshops are the best way to attract foreign investment and kick-start local economic development or speed up the rate of economic growth that will sooner or later trickle down and benefit all, locals and foreigners. And therefore, they are a blessing to the countries in which they are located. For example, it is said that sweatshop conditions are fair because they meet the economic rule of voluntary contracts between workers and employer (Powell and Skarbek 2004); and they are good because corporations actually pay more than local rates (ACIT 2000); that even their subcontractors pay more than local rates (Powell and Skarbek 2004); and therefore, they create needed jobs (Henderson 1997). Their argument is that sweatshops are good in social terms (basic wages and jobs); nothing is said about how good they are to locals in environmental terms (pollution/environmental degradation).

Hence, some people believe that social races to the bottom are good for the poor and see the lowering of wages even more that those in other poor regions of the world as a healthy way of attracting or keeping foreign investors. For example, Kristof (2006) states that the sweatshop model, especially if wages could be even lower than those in Asia or China could be a good poverty reduction model for Africa as then foreign investment would flow in and stay. And sometimes, sweatshops are sold as the solution to local poverty, but local populations may not be the beneficiaries of them. For example, U.S. Senator Dorgan (2006) when critiquing the position of Kristof (2006) points out that in the case of Jordan, foreigners were the beneficiaries of the sweatshop model there, not locals.

Critics of economic growth zones and traditional sweatshops are social and environmental agents and anti-sweatshop academics and individuals who believe that the social degradation and environmental degradation associated with them is unfair or immoral. Therefore, they are the source of bad social and environmental news in the places they are located as they do not provide even living wages and basic environmental benefits. For example, the organization Scholars Against Sweatshop Labour (SASL 2001) supports the aims of anti-sweatshops activists calling for the need to monitor sweatshops to ensure that corporations running them provide living wages and good working conditions to local workers; and if they do not comply, anti-sweatshop activists call for actions to be taken to press them to comply. It is expected that social threats aimed at market losses or shut downs would make corporations sustaining the sweatshops take social responsibilities seriously. Yet, it has been reported in the N.Y. Times that environmental issues are more likely to lead to sweatshop closures than social issues (Kristof and WuDunn 2000).

It is known that if an incentive based market model (e.g. economic model) is implemented without regulation (e.g. social and environmental) or with ineffective regulation (e.g. social and environmental), it will lead sooner or later to abuse/market failure. For example, inappropriate regulation is believed to be one of the major factors leading to the 2008 collapse of the global financial system, an economic incentive model, leading to a call for more effective regulatory and monitoring systems (IMF 2009). It has been pointed out that when creating markets we should make sure that there is self-interest-regulation consistency to ensure that human rights friendly development takes place as we then can have responsible self-interest (Muñoz 2005, P. 600).

And since the sweatshop model is an economic only incentive model implemented with little or no effective regulation by design it is ruled by irresponsible self-interest, and therefore, it should be expected that sooner or later it would lead to abuse/market failure and be subjected to ongoing social and environmental unsustainability. It has been stressed recently that a dominant-dominated system where maximization, partial regulation, and system dominance are the drivers is not sustainable; and this unsustainability will work through time against the dominated counterpart (Muñoz 2002). And in the case of especial economic zones and traditional sweatshops where there is minimal or no regulation, then the forces of maximization and system dominance should be expected to work at their best against the dominated counterpart.

Concerns have been pointed out about the unfair local and global nature of sweatshops. For example, it has been indicated that you do not need to go to developing countries to find extreme sweatshop conditions, they exist in the USA too (Reich 2001); there has been reports of attempts to cover up sweatshops conditions in Chinese factories (Fuller 2006) and of sweatshop probes into their working conditions (Espiner 2009); recent surveys in factories in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka showed that sweatshop’s conditions are getting worse, not better, despite of supposedly being a main issue to the high end corporations they supply (Gould 2006); difficult sweatshop conditions have been described in Latin America (BBC 2011; USLEAP 2011), Central America (Wirpsa 1995), and in North America (Ching Louie 1998).

Therefore, If we view sweatshops as socially and environmentally unresponsive models, then it should be expected that the so called voluntary economic contracts would work against local social and environmental stakeholders over time; and that given that global actors are in better position than local actors to bring sweatshops activities within social and environmental sustainability rules, then anti sweatshop activists have a point in advocating externally driven monitoring and pressure programs on corporations running sweatshops.

The view above appears to be consistent with the view of Miller (2003) who points out that sweatshops would work well under the economist’s voluntary contract rule if implemented under effective and enforceable local regulation. Because effective local regulation is absent anti sweatshop activists advocate the external action and monitoring of better living and working conditions in sweatshop environments. And Friends of the Earth (FE 2004) pointed out with respect to the working of the pure economic system and its social and environmental externalities that a) the poor get less economic benefits and more pollution; b) regulation is often designed to work against the poor; c) that governments are under pressure to minimize or eliminate protections on the poor; and d) that placing profit first is the main cause of environmental degradation and social inequalities.

Moreover, it has been strongly indicated that sweatshop conditions would not exist if there was political courage to act in ways that reshape traditional economic thinking to ensure that this is so (Hickel 2011); and currently there is a campaign in the UK using the Olympics to encourage its suppliers to ensure good working conditions are provided to the workers producing goods for the 2012 Olympics (WOW 2012).

c) The grounds for paradigm shift

Since the publication of “Our Common Future” in 1987 (WCED 1987), it became increasingly more difficult to down play/ignore environmental and social issues as the report called for making development consistent with social and environmental concerns. In other words, the report called for making traditional economic development models consistent with sustainability rules. However, instead of a move towards sustainability, a move towards the eco-economic model or the model of eco-economic partnerships usually under the name of sustainable development has taken place. In other words, the dominant development model today is the eco-economic model, and current development issues and solutions should be addressed using eco-economic thinking and acting. It has been pointed out that there is a tendency to treat sustainability issues as sustainable development issues or vis a vis, and that this is wrong as then we are violating the theory-practice consistency principle when doing so (Muñoz 2009, P.3).

2) Eco-economic growth zones

a) What are they?

As eco-economic growth zones are being planned within the same line of thinking and structure as economic growth zones, albeit with the added condition that they be environmentally friendly this time, then the following can be said a) that eco-economic growth zones are or will be special areas or regions or places dedicated to the promotion of eco-economic growth only; b) that low carbon growth zones are or will be eco-economic growth zones dedicated only to eco-economic activity that is low carbon; and c) that green sweatshops are or will be the extreme versions of eco-economic/low carbon growth zones where eco-economic goals can be maximized as the social limits to eco-economic growth are or will be kept minimal or non-existent for the model to work best.

Eco-economic growth zones can be or will be export oriented or import-export oriented or import oriented. Just as economic growth zones were and still are treated different in terms of laws/regulations/taxes than other areas of the same country/region/ community to make them appealing to big investors especially foreign investors, eco-economic growth zones too will be treated different than other areas in those terms, but this time the goal is or will be to attract big environmentally friendly investors. Notice here that as environmental concerns become binding traditional sweatshops will become green sweatshops; and new sweatshops will be from the beginning green sweatshops.

As a result of this special eco-economic only purpose, eco-economic growth zones/low carbon growth zones and green sweatshops should be expected to be associated with races to the social bottom within and between countries every where in the world where they are or will be located just as the pure economic model has done. Social races to the bottom induced by eco-economic forces should be expected to be similar or worse than those generated by the pure eco-economic model as this time pressures on society will come not just from capitalist but from environmentalist too. Given a choice, green sweatshops will be located in the community within a country or in the country with the lowest social cost.

To compete, other communities in the country and other countries will see an incentive in offering a lowering of social costs to be able to attract environmentally friendly investment and green jobs, and this process is the one called social race to the bottom. And therefore, eco-economic zones/green sweatshops have or will have two types of negative impacts: a) an internal impact or direct impact on social conditions within its boundaries; and b) an external or indirect impact when inducing the migration or relocation of green production, labour, and pollution, and affecting regulatory standards outside its boundaries.

b) Supporters and critics

The supporters or proponents or promoters of eco-economic growth zones/low carbon growth zones and green sweatshops are eco-economic agents/eco-capitalist, academics and individuals concerned with environmental degradation under the simplistic notion that these eco-economic zones and green sweatshops are the best way to attract eco-friendly foreign investment and kick-start local eco-economic development or speed up the rate of eco-economic growth that in theory, seldom in practice, will sooner or later trickle down and benefit all, locals and foreigners. The need to bring the economy within ecological limits and ensure economic growth that is environmentally friendly was pointed out by Brown (2002); Soon after in Texas, Motloch et al (2008) started to encourage the business community to abandon the old economic paradigm and move towards the new eco-economic wave and adapt to remain competitive; and now promoting green growth development has become a true priority in developed countries and globally (OECD 2011).

Interest in reconciling economic development and environmental problems such as climate change is leading even financial institutions such as the World Bank to advocate the move towards a financial economic system that prefers low carbon development (WB 2008a) so we can move from a model of climate dumb development to one based on climate smart development (WB 2010), a strategy that local governments in developed countries are finding interesting. For example, Cernetig (2009) highlights that low carbon growth zones are being planned to be implemented and tested in Vancouver, BC, Canada and in San Francisco, California, USA, at the same time and in the same line of thinking as special economic zones with the goal of attracting environmentally friendly businesses. Creating this way carbon constrained industrial zones seeking to operate too at the lowest social cost possible. Hence, eco-economic growth zones/green sweatshops will share the same characteristics of special economic zones/traditional sweatshops in terms of laws/regulation/taxes, but they are expected to be environmentally responsible.

There seem not to be many direct critics of eco-economic development/eco-economic growth zones/low carbon growth zones/green sweatshops despite their social sustainability gap as academics and individuals appear to still be taking eco-economic issues as pure economic issues or believing that today’s market is still a pure economic market when it is not as it is an eco-economic market. It has been pointed out that the eco-economic model and market is different from the pure economic development model and market, yet eco-economic issues are apparently being addressed with the views of the old pure economic paradigm ((Muñoz 2000), a clear theory-practice inconsistency similar to that of addressing sustainability issues with sustainable development tools (Muñoz 2009).

The implementation of eco-economic models, especially in developing countries, is leading to land crises and food crises, yet these crises are presented as if they were pure economic dilemmas, not eco-economic crises. For example, food crises associated with diverting agricultural land to environmental uses (conservation/protection/global warming), are eco-economic issues, yet they are reported apparently as a pure economy only issues (Holmes 2008 ; Chakrabortty 2008); and land use crises resulting from diverting agricultural production to the biofuel/bioenergy industry are also eco-economic problems, yet they are being approached as a pure economic issues (IEA-B 2009).

Global research and financial institutions appear to be approaching the impact, mitigation, and adaptation to development under global warming (IPCC 2007) or the financing of low carbon development (WB 2008a) or the promotion of low carbon as climate smart (WB 2010) as improvements of the pure economic model, without clearly calling it an eco-economic approach to development issues. World leaders are meeting to discuss the weaknesses of the economic system while currently living within an eco-economic system (WS 2009a; WS 2009b). The United States is the only country that has not ratified the Kyoto Protocol (EE 2009) and Canada is exiting it (BBC 2011) to continue to promote officially economic growth only, not eco-economic growth.

c) The moral dilemma facing environmentalism today

As mentioned above, environmentalists have openly criticised the social injustice associated with the pure economic model, but now they are part of the dominant paradigm of eco-economic development; and therefore, they are partially responsible now for current and future social inequalities and races to the bottom. The question that highlights the moral dilemma facing environmentalism today is the following: Is social exploitation or social inequality or a race to the social bottom no longer a moral issue if it is done in the name of the environment and eco-economic development?

d) The grounds for future paradigm shift

In the near future, it will be increasingly more difficult to down play/ignore social concerns as lack of regulation/social justice and the dynamics of maximization and system dominance will lead to the lowest social bottom possible; and this will create the conditions for a rapid shift of paradigm from the eco-economic model to the sustainability model or the model of socio-eco-economic partnerships to avoid a global social collapse. There are social limits to eco-economic development (Muñoz 2003), and as we push those social limits towards the breaking point, paradigm shift or system collapse will take place. UN (2009) warns world leaders that now is the time to make the structural adjustments required to move towards sustainability as to avoid leading humanity towards disaster.

It is known that the social dissatisfaction with economic systems failing to champion the wellbeing of the majority has been one of main factors leading to social movements such as the Arab Spring, movements that are now even reshaping or changing the way aid is provided to developing countries, especially those with authoritarian regimes (TAP 2011). And it is becoming clear now that social dissatisfaction with the working the economic system in the USA in favour of only 1% percent of its population is behind the recent social movement called “Occupy Wall Street” in New York, which is reported, supported by surveys, to be more popular than one think (Montopoli 2011).

Therefore, it is known or accepted now that without meeting even basic social needs, we cannot expect people to be pro-economic development or pro-eco-economic development. As pointed out by Geddes (2003), there can no be social interest in preservation or environmental quality goals unless first people have the per capita income needed to meet their basic needs. Pressures to truly meet those basic social needs will sooner or later lead to first concrete steps towards paradigm shift in the direction of sustainability. For example, organizations within the United Nations in charge of development and environmental issues are taking direct steps into helping development planners and practitioners with the integration of poverty and environmental issues by releasing a handbook on how to do that, clearly recognizing that sustainability can not take place unless we incorporate poverty issues (UNDP and UNEP 2009)

3) The need to understand the sustainability implications of green sweatshops

The discussion above raises very relevant moral questions: Are green sweatshops better in social term than the previous pure economy sweatshops? Should we instead be focusing our attention on planning and implementing sustainability growth zones? An insight into these questions is gained when expressing these issues in simple qualitative comparative ways aimed at uncovering the sustainability implications of green sweatshops.

Objectives

To express using simple qualitative comparative terminology and techniques the structure of the pure economic system/traditional sweatshop and highlight their main characteristics and sustainability gaps;

To extend the framework above to point out the structure of the eco-economic system/green sweatshop and present their main characteristics and sustainability gaps;

To use these frameworks and analysis to show that without effective social regulation eco-economic growth zones/green sweatshops may lead to similar or worse social races to the bottom that the ones generated by the previous pure economic model or traditional sweatshops.

Methodology

First, the qualitative comparative terminology used to present the ideas in this paper is introduced.

Second, relevant operational concepts are listed.

Third, the structure of the pure economic model and its associated sustainability gaps is presented.

Fourth, it is pointed out that as the pure economic sweatshop is an extreme version of the pure economic model it has the same paradigm structure.

Fifth, all the possible evolutionary paths towards sustainability available to the pure economic system/pure economic sweatshop are shown and discussed.

Sixth, it is said that some possible evolutionary paths are illogical and that only one is logical for the pure economic model/ sweatshop to follow to maintain its dominance and to avoid socialization.

Seventh, the structure of the eco-economic model and its associated sustainability gaps is stressed.

Eight, it is indicated that as the green sweatshop is an extreme version of the eco-economic model or eco-economic growth it has the same paradigm structure.

Ninth, it is mentioned that without social regulation green sweatshops will lead to races to the social bottom driven this time by eco-economic programs.

Tenth, it is indicated that one way of making green sweatshops consistent with sustainability rules is by adding social friendliness into the paradigm mix.

And finally, some relevant conclusions are provided.

Terminology

A = Social goals matter

B = Economic goals matter

C = Environmental goals matter

PE = Pure Economic system

EE = Eco-Economic system

S = Sustainability

SG = Sustainability Gap

SGZ = Sustainability growth zones

|

a = Social goals do not matter

b = Economic goals do not matter

c = Environmental goals do not matter

PES = Pure Economic Sweatshop

GSS = Green Sweatshops

ESG = Environmental Sustainability Gap

SSG = Social Sustainability Gap

EESSG = Eco-economy social sustainability gap

|

Operational rules

1) Merging rules

If “A” and “B” are dominant characteristics and “a” and “b” are their dominated counter parts, the following is expected when system mergers take place:

a) Merging under dominant-dominated interactions

Under these conditions, the dominant system prevails as shown below:

(Aa) → A

(bB) → B

(Aa) (bB) → AB

b) Merging under dominant-dominant interactions

Under these conditions, dominance prevails as indicated:

(AA) → A

(BB) → B

(AA) (BB) → AB

c) Merging under dominated-dominated interactions

Under these conditions, the dominated form prevails as shown:

(aa) → a

(bb) → b

(aa) (bb) → ab

2) Sustainability gaps (SG)

a) When there are dominant-dominated system interactions and there are no win-win situations or merging solutions there are sustainability gaps.

For example, if system M1 = Ab and system M2 = AB, and A = social goals dominant and B = economic goals dominant, then their merger can be expressed as follows:

M = M1.M2 = (Ab) (AB) = (AA) (bB) = A (bB).

Hence model M has one sustainability gap (SG = bB) in the economy side. As long as this sustainability gap (bB) in the economy exists, there will be economic unsustainability and the model M would remain as stated below as no full merging can take place.

M = A (bB)

Hence, the sustainability gap affecting the economy would make this model very unsustainable.

b) When there are dominant-dominated system interactions and there are win-win situations or merging solutions there are no sustainability gaps.

Now if the sustainability gap (SG = bB) in model M above is closed due to the existence of win-win economic situations[ (bB → B)], then sustainability can take place, and now that the economy is in dominant form (B) full merging would take place and then model M would be:

M = AB

See that under sustainability there are no sustainability gaps as model M above shows.

The pure economy model

a) The structure

The model where only the economy matters is called here the pure economic system (PE), which can be expressed in conjunctural terms as follows:

PE = aBc

Hence the pure economic model (PE) is the one where society and environment exist only to support economic goals and programs.

b) The sustainability gaps (SG)

To point out the sustainability gaps associated with the pure economic model (PE) we can restate the formula above as follows:

PE = aBc = (aB) (Bc)

Notice that in the model above there are two types of sustainability gaps, the social sustainability gap (SSG = aB) and the environmental sustainability gap (ESG = Bc). Hence since in this model only economic factors matter when producing goods and services, then economic growth zones should be expected to lead to social races and environmental races to the bottom at the same time. Therefore, production will take place or will be relocated to those areas within a country or to specific countries where the social and environmental limits to economic growth are minimal or nonexistent. This is because the places or countries with the lowest social and environmental cost will be more attractive to rational investors/capitalists.

The structure of the pure economy sweatshop

Since traditional or pure economic sweatshops (PES) are the extreme version of economic growth zones, they have the same model structure as the pure economic system so it can be stated as follows:

PES = aBc

And since they usually have the status of special/law-regulation exempt zones, then traditional sweatshops are the places where races to the social and environmental bottom are to be maximized. Hence it can be seen that pure economic sweatshops work better when there are no social and environmental regulations or where they face the lowest social and environmental cost; and in those places, these pure economic sweatshops will flourish. Notice that here social and environmental races to the bottom are driven by economic issues only.

Implications:

If only economic factors will determine what will be produced, then pure economic growth zones will lead to pure economic sweatshops being located in the areas, places, countries with the lowest social and environmental cost or with the lowest social-environment justice standards or regulation, leading to increasingly deeper and deeper social and environmental races to the bottom. And the failure to address the social and environmental races to the bottom underlying the pure economic model (PE)/sweatshop (PES) is creating the conditions for paradigm evolution towards sustainability (S) with expected first stop in the eco-economic model (EE).

Possible evolutionary paths towards sustainability for the pure economic system/pure economic sweatshops.

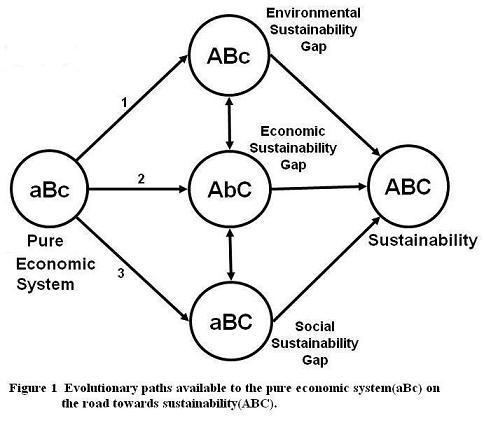

Figure 1 below shows the different evolutionary possibilities that the pure economic system/sweatshop (aBc) can follow in search a sustainability position (ABC).

a) The socio economy path

Point 1 in Figure 1 shows that the pure economic system (aBc) can move towards the socio-economic model (ABc) first by closing the social sustainability gap (aB) and adding social concerns in dominant form (A) and keeping the environmental sustainability gap (Bc) and from there find its way towards sustainability (ABC).

Notice that under the socio-economic model (ABc) there is only one race to the bottom and it is in environmental terms.

b) The inverse model path

Point 2 in Figure 1 indicates that that the pure economic system (aBc) can move towards the inverse model or the socio-environmental model (AbC) first by losing its dominance and closing the social sustainability gap (aB) and closing the environmental sustainability gap (Bc) and adding social concerns in dominant form (A) and environmental concerns in dominant form (C) and from there find its way towards sustainability (ABC).

Notice that under the socio-environmental model (AbC) there is only one race to the bottom and it is in economic terms.

c) The Eco-economy path

Point 3 in Figure 1 demonstrates that the pure economic system (aBc) can move towards the eco-economic model (aBC) first by closing the environmental sustainability gap (Bc) and adding environmental concerns in dominant form (C) and keeping the social sustainability gap (aB) and from there find its way towards sustainability (ABC).

Notice that under the eco-economic model (aBC) there is only one race to the bottom and it is in social terms.

Logical evolutionary paths towards sustainability available to the pure economic model/sweatshop

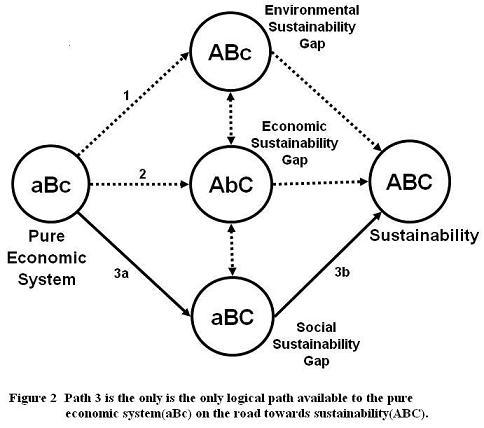

Figure 2 below indicates that some of the evolutionary paths available to the pure economic/sweatshop model are illogical paths and that only one path is logical towards sustainability. See that a broken line indicates illogical path and continuous line means logical path.

a) The Illogical paths

As shown in Figure 2 above both the socio-economic path (Point 1) and the inverse model or socio-environmental path (Pont 2) are illogical paths from the point of view of the pure economy model. A move from a pure economy (aBc) to the socio-economy (ABc) is illogical simply because the economy has been always allergic to socialization and it will avoid it. The socialization of the market runs against traditional pure market philosophy and therefore it should not be expected to happen. A move from the pure economic model (aBc) to the socio-environmental model (AbC) is illogical because economic agents should not be expected to give up their dominant position anytime soon.

b) The only logical path

As indicated in Figure 2 by the continuous line there is only one logical evolutionary path available to the pure economic system (aBc) and it involves a move first towards an eco-economy form (aBC) as indicated by the continuous line 3a and then a move towards sustainability (ABC) as represented by the continuous line 3b. By first moving towards the eco-economy (EE), the pure economic model (PE) avoids socialization and it keeps its dominant position. In other words, the eco-economic model (EE) provides the only evolutionary alternative available to the pure economic system to avoid socialization and to continue keeping its dominance. And this may explain why the eco-economic model is the dominant paradigm today.

The eco-economy model (EE)

a) The structure

Hence the structure of the eco-economy (EE) replacing the pure economic system (PE) can be indicated in conjunctural form as follows:

EE = aBC

Notice that in this eco-economic model (EE) society is there only to support eco-economic development as it is assumed to be a passive player.

b) The sustainability gaps (SG)

The model above also shows that in this eco-economic model (EE) there is only one sustainability gap and only one race to the bottom, and it is a social one. In other words, the only sustainability gap (SG) within the eco-economic model (EE) is the eco-economy social sustainability gap (EESSG); and this can be indicated as follows:

EE = (a) (BC)

Therefore, it can be said that in this EE model society is out there only to meet eco-economic goals and its issues and externalities are exogenous to the system. And as long as social concerns are passive or exogenous or outside the model the eco-economy social sustainability gap (EESSG) will persist and be a source of ongoing unsustainability. And any low carbon growth zone will reflect the eco-economic structure and therefore eco-economic growth within them will lead to races to the social bottom, but this time it will not be only economic issues driving the race, but eco-economic issues. And hence, production will take place or will be relocated to those areas within a country or to specific countries where the social limits to eco-economic growth are minimal or nonexistent. This is because the places or countries with the lowest social cost will be more attractive to rational environment friendly investors/eco-capitalists.

Notice that the following is also true:

EE = (PE)C = (aBc)C = (aB) (cC) = aBC

The model above says that we can extract the eco-economic model (EE) by adding environmental concerns in dominant form (C ) to the pure economic model (PE = aBc) following expected merging rules. In other words, the model above indicates that if we make environmental concerns binding (C), the pure economic model (PE) becomes an eco-economic model (EE). And the eco-economy social sustainability gap (EESSG) still remains[ (a) (BC)].

The structure of the green sweatshops

Since green sweatshops can be viewed as the extreme version of eco-economic growth zones or low carbon growth zones, then they have the same model structure as the eco-economic system:

GSS = aBC

Notice that here too there is only one race to the bottom and it is a social one. And since these sweatshops have or will have the status of special/law-regulation exempt zones, green sweatshops are or will be the places where races to the social bottom are or will be maximized. Therefore, it can be seen that green sweatshops will, just as the pure economic sweatshops do, work better when there are no social regulations, and in those places, these green sweatshops will flourish. Notice that here social races to the bottom are driven by both economic and environmental issues at the same time as the eco-economy social sustainability gap (EESSG) is still active within green sweatshops.

See that the following is also true:

GSS = (PES)C = (aBc)C = (aB) (cC) = aBC

The model above says that we can extract the green sweatshops (GSS) by adding environmental concerns in dominant form (C ) to the pure economic sweatshop (PES = aBc) following expected merging rules. In other words, the model above indicates that if we make environmental concerns binding (C), the pure economic sweatshop (PES) becomes a green sweatshop (GSS).

Notice too that the green sweatshops (GSS) have a social sustainability gap (EESSG) just as the pure economic sweatshops (PES) had a social sustainability gap (SSG) so both models, without regulation, should be expected to be socially unfriendly.

Implications:

If only eco-economic factors will determine what will be produced, then eco-economic growth zones will lead to green sweatshops being located in the areas, places, countries with the lowest social cost or with the lowest social justice standards or regulation, leading to similar or worse social races to the bottom than those of the pure economic sweatshops as now they will be facing double pressure at the same time, economic and environmental. In others words, the eco-economic driven race to the social bottom should be expected to be socially unfriendly too.

And the failure to address the social races to the bottom underlying the eco-economic model/green sweatshop will lead in the long-term and without social regulation to paradigm evolution towards sustainability if a global social collapse is to be avoided or lead to wide spread social collapse and strife.

How to make green sweatshops consistent with sustainability rules

If sustainability was the goal, then instead of planning and implementing green sweatshops, we should be planning and implementing sustainability growth zones (SGZ); and that way we would be ensuring that growth meets social, economic, and environmental goals at the same time. Below is a suggestion of how to ensure that green sweatshops (GSS)/eco-economic model (EE) meet sustainability rules, creating in the process sustainability growth zones (SGZ):

a) The approach analytically

Sustainability (S) can be achieved by adding social responsibility (A) to green sweatshops (GSS) as indicated below:

S = A (GSS) = A (aBC) = (Aa) (BC) = ABC Since Aa → A

S = ABC

As shown above, sustainability (S) comes from eliminating the social sustainability gap (Aa) affecting the green sweatshop (GSS) by incorporating social concerns (A). And by doing this we are creating a sustainability growth zone (SGZ). In other words, the model above indicates that if we make social concerns binding (A), the green sweatshop model (GSS) becomes a sustainability model (S); and therefore, a sustainability growth zone (SGZ).

b) The approach graphically:

Figure 2 above shows by the continuous line 3b that the next step of the eco-economic system (EE = aBC) towards sustainability (S = ABC) is to eliminate the social sustainability gap (Aa), which can be presented as follows:

S.EE = (ABC) (aBC) = (AaBBCC) = (Aa) (BC)

Hence, contrasting sustainability (S) with the eco-economic model (EE) leads to the social sustainability gap (Aa) that needs to be eliminated so this model fulfils sustainability rules; and therefore the rules of sustainability growth zones (SGZ).

When closing the social sustainability gap (Aa), then EE → S, and therefore the following is true:

S.S = S , where EE = S

In other words, the model above indicates that if we close the social sustainability gap (Aa), the eco-economic model (EE) becomes a sustainability model (S); and therefore, a sustainability growth zone (SGZ).

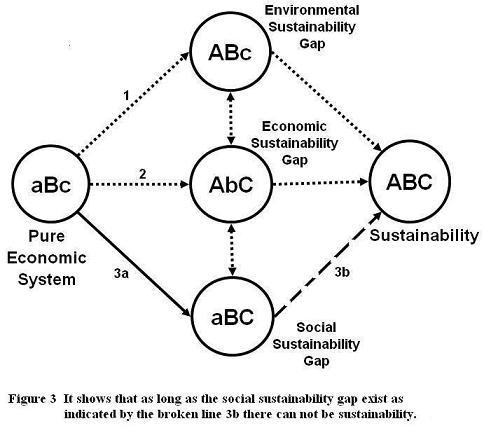

c) Green sweatshops under persistent social unsustainability

Figure 3 below shows that as long as green sweatshops (GSS) do not address the social sustainability gap (SSG) as indicated by the broken line 3b they will be subjected to persistent social unsustainability.

In other words, Figure 3 above indicates that as long as green sweatshops (GSS) persist, the social sustainability gap (SSG) will persist; and therefore, sustainability (S) can not be achieved.

d) Implications:

There is a need to add social controls, internal and external, to eco-economic development models or eco-economic growth zones or green sweatshops to minimize or eliminate races to the social bottom in existing zones and to avoid them in newly established zones. It should be expected that without social regulation the eco-economic induced social race to the bottom may be as bad as or worse than the social race to the bottom created by the pure economic model as now pressures on society will come from both economic agents and environmental agents at the same time, not just economic agents as before. The sooner social issues are addressed; the sooner sustainability will take hold. Notice that under sustainability growth zones (SGZ); and sustainability (S), there are no races to the bottom.

Conclusions

The structures of both the traditional sweatshops and the green sweatshops and their associated sustainability gaps and races to the bottom were pointed out. It was stressed that just as the pure economy sweatshops were socially unfriendly green sweatshops are too as they share the social sustainability gap. In other words, it was pointed out that the eco-economic model and green sweatshops can be as bad as or even worse than in the pure economic model and the pure economic sweatshops in social terms as now we have both economic and environmental agents driving the social race to the bottom.

And therefore, to make the green sweatshop a better model than the pure economy sweatshop we have to subject it to effective social regulation from the beginning so that besides meeting eco-economic goals we can meet our social responsibilities. Notice that when doing so we are creating the conditions needed for the existence of sustainability growth zones. If we fail to do so, in the long-term and without social regulation a global social breakdown will slowly take place and lead either to a forced paradigm shift towards sustainability or lead to widespread global social action against the eco-economic model and green sweatshops.

References

Academic Consortium on International Trade (ACIT), 2000. Letter to Presidents of American Universities and Colleges Regarding Anti-Sweatshop Campaigns, ACIT Steering Committee, July 29, University of Michigan, MI, USA.

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), 2011. Canada Under Fire Over Kyoto Protocol Exit, News USA and Canada, December 13, London, UK.

Brown, Lester, 2002. The eco-economic revolution: Getting the market in Sync with nature, The Futurist, World Future Society, March, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Cameron, David (2011). Governance for Growth: Building Consensus for the Future, Report Produced at the Request of the President of France and G20 Presidency Chair, Nicolas Sarkosy, for the 2011 G20 Summit in Cannes, Prime Minister’s Office, P. 33, London, UK.

Cernetig, Miro, 2009. Robertson Eyes ‘Low-Carbon’ Growth Zones, The Vancouver Sun, Section A, Opinion, October 02, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Ching Louie, Miriam (1998). Life on the line, New Internationalist Magazine, Issue 302, June 05, Northamptonshire, UK.

Dinmore, Guy and Ralph Atkins, 2009. G8 set to Push for a Return to 'Ethics', Financial Times, June 29, London, UK.

Dorgan, Byron L. (2006). Sweatshops in Africa? Consider the Case of Jordan, U.S. Senator from North Dakota’s Letter to the Editor, June 07, The New York Times, New York, NY, USA.

Espiner, Tom (2009). Tech Coalition Launches Sweatshop Probe, ZDNet UK, February 16, London, UK.

Ethical Energy (EE), 2009. Strategy for Post 2012 Kyoto Protocol Agreement, July, Ahmedabad, India.

Friends of the Earth (FE), 2004. Poverty, Justice and the Environment, Booklet, London, UK.

Fuller, Thomas (2006). 'Sweatshop snoops' take on China factories - Asia - Pacific - International Herald Tribune, September 15, Asian Pacific Section, The New York Times, New York, NY, USA.

Geddes, Pete, 2003. Trade and the Environment: A Race to the Bottom?, Bozeman Daily Chronicle, November 26, Bozeman, MT, USA.

Gould, Dan (2011). Sweatshops Are Still Supplying Major Brands, April 29, The Guardian, London, UK.

Henderson, David, 1997. The Case for Sweatshops, The Weekly Standard, February 7, The Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA.

Hickel, Jason (2011). Rethinking Sweatshop Economics, Foreign Policy in Focus, July 01, Washington DC, USA.

International Labour Office (ILO), 2003. Employment and Social Policy in Respect of Export Processing Zones (EPZs), Committee on Employment and Social Policy, March, Geneva, Switzerland.

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2009. Lessons of the Financial Crisis for Future Regulation of Financial Institutions and Markets and for Liquidity Management, February 04, Monetary and Capital Markets Department, Washington, D.C. , USA.

Kristof, Nicholas D. (2006). In Praise of the Maligned Sweatshop, The Opinion Pages, New York Times, June 06, New York, NY, USA.

Kristof, Nicholas D. and Sheryl WuDunn, 2000. Two Cheers for Sweatshops, New York Times, September 24, New York, NY, USA.

Milberg, William and Matthew Amengual, 2008. Economic Development and Working Conditions in Export Processing Zones: A Survey of Trends, Working Paper No. 3, International Labour Office, Geneva, Switzerland.

Miller, John, 2003. Why Economists Are Wrong About Sweatshops and the Ant sweatshop Movement, Challenge, Vol. 46, No. 1, January-February, pp. 93-122, M E Sharpe Inc, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Montopoli, Brian, 2011. Occupy Wall Street: More popular than you think, October 13, CBS News, New York, NY, USA.

Motloch, John, J. David Armistead, and Jon Lebkowsky, 2008. Eco-Economics in Texas: Competitive Adaptation for the Next Industry Revolution, Texas Business Review, October, Austin, Texas, USA.

Muñoz, Lucio, 2000. An Overview of Some of the Policy Implications of the Eco-Economic Development Market, Environmental Management and Health, Vol. 11, Issue 2, Pp. 157-174, MCB University Press, Bingley, U.K.

Muñoz, Lucio, 2002. Maximization, Partial Regulation, and System Dominance: Can They Be Drivers of True Sustainability?, Environmental Management and Health, Vol. 13, No. 5, Pp. 545-552, MCB University Press, Bingley, U.K.

Muñoz, Lucio, 2003. Eco-Economic Development Under Social Constraints: How to Redirect it Towards Sustainability?, THEOMAI, Issue 8, October, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Muñoz, Lucio, 2005. Private and Public Sector Interfaces: Prerequisites for Sustainable Development, Sustainable Development Policy & Administration, Chapter 26, Pp. 590-609, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, Fl, USA.

Muñoz, Lucio, 2009. Beyond Traditional Sustainable Development: Sustainability Theory and Sustainability Indices Under Ideal Present-Absent Qualitative Comparative Conditions, Mineria Sustentable, REDESMA, Vol.3 (1), March, La Paz, Bolivia.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2009. G8 Summit to discuss principles and standards for global business dealings, Paris, France.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2011. Towards Green Growth, Paris, France.

Powell, Benjamin and David Skarbek, 2004. Sweatshops and Third World Living

Standards: Are the Jobs Worth the Sweat?, Independent Institute, Working Paper Number 53, Oakland, CA, USA.

Reich, Robert (2001). American Sweatshops, The American Prospect, December 19, Washington, D.C., USA.

Scholars Against Sweatshop Labour (SASL), 2001. Response from Scholars Against Sweatshop Labor to ACIT’s Letter to Presidents of American Universities and Colleges of July 29, 2000, SASL Steering Committee, October 22, Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA.

The Associated Press (TAP), 2011. EU: Arab Spring sparks change in bloc's aid plans,

October 13, New York, NY, USA.

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) (2011). Fashion Chain Zara Acts on Brazil Sweatshop Conditions, News Latin America and Caribbean, August 18, London, UK.

United Nations (UN), 2009, The Millennium Development Goals: Report 2009, New York, USA.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2009. Mainstreaming Poverty-Environment Linkages into Development Planning: a Handbook for Practitioners, UNDP-UNEP Poverty-Environment Initiative, New York, USA.

U.S. Labor Education in the Americas Project (USLEAP) (2011). Winter 2011 Newsletter, Issue 4, Chicago, IL, USA.

War On Want (WOW) (2012). Playfair 2012 Campaign – Take Action for Workers Supplying the Olympics, London, UK.

Wirpsa, Leslie (1995). Women Risk Jobs to Denounce Maquilas: U.S. Consumers Can Improve Conditions in Guatemala, El Salvador, National Catholic Reporter, April 14, Kansas City, MO, USA.

World Bank (WB), 2008a. Development and Climate Change: A Strategic Framework for the World Bank Group, Technical Report, Washington, DC, USA.

World Bank (WB), 2008b. Special Economic Zones: Performance, Lessons learned, and Implications for Zone Development, FIAS, April, Washington, DC, USA.

World Bank (WB), 2010. World Development Report 2010: Development and Climate Change, Washington, DC, USA.

World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), 1987. Our Common Future, Oxford University Press, London, U.K.

World Summit (WS), 2009a. Chair’s Summary, July 10, L’Aquila, Italy.

World Summit (WS), 2009b. G5 Political Declaration, July 8, L’Aquila, Italy.

Zeng, Douglas Zhihua, 2011. How Do Special Economic Zones and Industrial Clusters Drive China’s Rapid Development?, PRWP 5583, March, The World Bank, Africa Region, Finance & Private Sectors Development, Washington, DC, USA.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lucio Muñoz is a Qualitative Comparative Researcher/Consultant, Vancouver, BC, Canadá. He can be contacted at munoz@interchange.ubc.ca.