I know a scholar who makes a living valuing natural capital and ecosystem services, with trips the world over pointing out the value of standing forests, free-flowing watersheds, coastal wetlands, and all those other “funds” of ecosystem services. Foreign governments, think tanks, and universities pay handsomely for such talks. It’s a good gig for those who can settle for telling half a story.

Meanwhile the inconvenient truth languishes in obscurity. Our scholarly fellow (and numerous followers) won’t be seen uttering the phrase “steady state economy,” at least not in public. He knows that goes against the political tide, which is still coming in for economic growth. That’s why, after this fellow comes through your town or country, you’re left to figure out the macroeconomics on your own. By the time you realize that all the talk about ecosystem services and “green accounting” boils down to the need for a steady state economy, you’ll be left to do the heavy political lifting, too. Our traveling scholar will be long gone; probably on another flight to a hefty honorarium.

Let’s get one thing straight: ecological microeconomics — deriving the value of ecosystem services — does have an important role to play in the quest for sustainability. But performed out of its macroeconomic context, all the talk of ecosystem service values is like the din of drums without the melody of a guitar. You can’t really get the point of it (and you’re likely to get very bored).

For the sake of all sustainable, I’d like to pull a Bill Maher and propose a “new rule,” namely, that no talks on valuing ecosystem services be given (especially for big bucks) without a healthy dose of ecological macroeconomics. Without explicitly pointing out the limits to economic growth and the need for a steady state economy, the speaker leaves the audience with a dangerous ambiguity. Suckers and scholars alike are led to believe they can save the world as long as they get the prices right for ecosystem services. Of course, some of the audience will “get it” — it being the need for a steady state economy — but too much ambiguity remains to turn the tide toward steady statesmanship.

This is no hypothetical matter. We see examples abounding. Take the National Wildlife Federation (NWF), which recently adopted a resolution calling for reforming GDP, which is THE indicator of economic growth. NWF fully recognizes that GDP is a poor indicator of human wellbeing because it doesn’t account for many things — such as wildlife conservation — that are important to humans. They recognize that growing GDP has amounted to declining biodiversity, among other things. That’s why it is quite logical to surmise that NWF gets the need for a steady state economy.

But no, NWF clarified that they only call for reforming GDP and not for a steady state economy. Apparently they think that, by getting all the prices right for ecosystem services, GDP will be wildlife-friendly and we can have economic growth and wildlife conservation ever after. (Actually, at least one of the NWF delegates who advanced the NWF resolution was motivated by steady state economics. We know that because he’s a

CASSE chapter director! For NWF executive leadership, however, apparently it’s all drums and no guitar.)

NWF would do well to consider Herman Daly’s metaphor of the plimsoll line, the marking on a ship that tells captain and crew when to stop adding cargo. Loading beyond the plimsoll line is so dangerous that it was outlawed. To the NWFs of the world, ecological macroeconomics has a message: when you’re loaded to the plimsoll line, it doesn’t matter if you add a green puppy or a gray pig — you’re sunk!

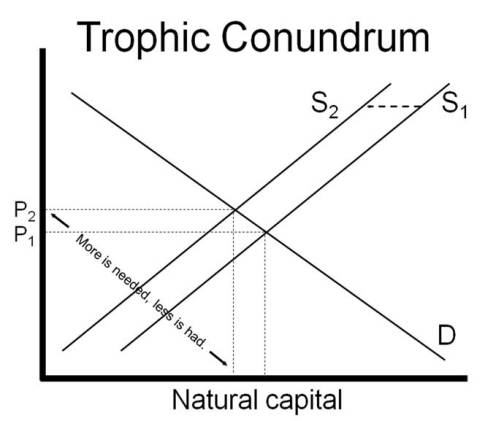

Failure to see the forest for the trees would be greatly alleviated if only our traveling salesmen of natural capital accounting were to couple the incomplete truth (micro) with the inconvenient truth (macro). I’ll make it easy for them by offering up the “trophic conundrum” model from my upcoming book, Supply Shock: Economic Growth at the Crossroads. The model illuminates the inconvenient truth that all the valuation exercises in the world won’t save us from the tradeoff between economic growth and environmental protection.

We see from the model that as the natural capital supply curve shifts inward (from S1 to S2), the price of natural capital and ecosystem services increases (from P1 to P2). That’s basic economics. What is not basic (conventional, neoclassical) economics, but rather ecological macroeconomics, is the trophic theory of money, which tells us that the supply curve shifts inward as an inevitable function of economic growth. That’s because economic growth entails the transformation of natural capital into more goods and services, plus manmade capital and waste.

We can do all the green accounting in the world, but the only way to stabilize prices of natural capital and ecosystem services — the only way to achieve sustainability — is to establish a steady state economy with stable population and per capita consumption. Meanwhile the only way to establish a steady state economy is with more, and clear, articulation of this inconvenient truth. Otherwise, with nothing but ecological microeconomics, we’re just pricing to peddle.

Brian Czech has a B.S. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, an M.S. from the University of Washington, and a Ph.D. from the University of Arizona. An active member of The Wildlife Society, he is a Certified Wildlife Biologist with 20 years of public service in federal, state, and tribal governments. Currently he is president of the Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy (CASSE). The mission of CASSE is to educate the public and policy makers on the fundamental conflict between economic growth and: 1) environmental protection; 2) economic sustainability; 3) national security, and; 4) international stability.