Introduction

During recent work to design easy measurement tools for development organizations seeking to meet international treaty commitments to "sustainable development," we were surprised by the size of the gap that these tools revealed between the agreed international standards and their policies and practices. We were further dismayed by the many kinds of rhetoric that organizations currently use to redefine "sustainable development." Despite what seems to be a relatively clear and scientific standard supported by international political agreement, organizations substituted a variety of other agendas (Lempert & Nguyen, 2008).

While some authors suggest that this gap is due to a lack of awareness or information (or to what some even call "slippage"), we start with the assumption used in contemporary economic and political science theory that international actors are perfectly rational. Given this assumption, the apparent behavioral contradictions logically suggest that sustainable development advocates and policy makers have been reluctant to acknowledge and address their actual motivations. We offer a theory as to the real motivations of different actors using participant observation field data from our work as an applied anthropologist and environmental policy practitioner, based on what some officials have confided to us regarding their personal fears, and we carry these assumptions to their logical conclusions. We do not seek to test the validity of the evidence or describe our methods in acquiring it in this conceptual article, but rather offer a logical test of the hypothesis itself within existing social science theory frameworks as a basis for future work and as a comparison with existing explanations. In future articles, we look forward to laying out a methodological agenda describing how various social science fields can use different types of data to challenge or confirm our hypothesis about fears and behaviors of government officials (information that is difficult to collect and verify, but that is informed by our fieldwork and scientific intuition from our respective fields) and for seeking proof to test the theory that follows from it.

We suggest that past experiences and fears of government leaders and officials in "developing" countries that have suffered international invasions and violence from more powerful countries largely influence their approaches to "sustainable development." We draw on the statements that we have heard from officials in countries that were invaded by foreign powers and from officials in neighboring countries as to their anxieties about future incursions and for their personal safety. We believe that these fears--which may be entirely rational--have led them to decisions that endanger their own cultures, undermine their countries' sustainable development, and put their minority cultures at continuing risk of extinction as they, themselves, were subject to exploitation under colonialism before their international recognition as leaders of nation states. At the same time, we suggest that the behaviors of actors in developing countries continue to play on or avoid addressing these fears.

We note that most development organizations currently focus on strategies of "raising awareness" on issues of sustainability, much as health campaigns centered on poor diet, smoking, and other risks focused on awareness. Yet, awareness may not really be the issue. There may be deeper psychological (cultural and cognitive) explanations for why both developed and developing countries appear unable to apply the standards they have agreed to, an explanation that is based either on self-interest or some distortion of self-protection and self-interest. If so, efforts would need to be redirected to the real source of the problem for change to occur.

In thinking through the issue, we apply the rational actor and game theoretic frameworks that economists and political choice theorists currently use. While these methods do not generate empirical results and are based on a set of logical assumptions of human behavior rather than on empirical confirmation, they offer a form of testing our hypothesis through modeling or thought experiment. They also generate additional hypotheses that other scholars and practitioners might further test. What makes our approach slightly different is that we link the rational actor approach with a psychological and anthropological framework. Rather than look at countries as similar actors pursuing merely economic self-interest, we suggest that countries and their leaders also make decisions based on their historical experiences, socialization, and fears. We draw from approaches like those of Graham Allison (1971) in seeking to explain national decisions using various frameworks, including the psychology of leaders as well as the socialization of individuals within different institutions. In examining the parallels between the colonial policies of European governments and the newly independent leaders with regard to their own "dependent" minorities (subject to hegemonic control), we also note how the training of current leaders under colonial rule often led to internal cultural continuities in many institutions after transference of authority to local leaders. These include policies of "internal colonization" and exploitation of the resources of minority communities, rather than support for independence, local sovereignty, and sustainable development (Wallerstein, 1974).

Though we take a bit of a tour of sustainable development approaches before coming back to our hypothesis, our goal is to look at the context and to try to eliminate some of the explanations that currently pass for common wisdom. We start by thinking through the different explanations that development actors have given for why they use different standards for sustainable development than the scientific consensus that was the basis for international agreement in the Rio Declaration in 1992. At a later point in the article, we offer explanations that individuals have given about their personal fears and motivations in governmental decisions. This qualitative methodological approach, which is the first step in generating hypotheses of social-cultural behaviors and a prelude to later quantitative work, is what anthropologists call the "emic," the internal perspective of actors on their own behavior.

At the same time, we look at the structural patterns of behaviors of cultures and countries that carry forward from the colonial period and how different countries may be "locked in" to certain patterns of interaction based on how they view their interests. We show how this logic or system of behaviors may be overriding their legal commitments and long-term interests in sustainable development. This is what anthropologists call the "ethic" or "deep structure," an outside perspective on interests and logic, a second step in qualitative observations and hypothesis formation of social-cultural behaviors.

We follow this discussion with a hypothesis for how the belief system and the logic of interests might fit together, based on our experiences in Southeast Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere with government officials who are aid recipients. We seek to understand how they try to fit the ideas of "sustainable development" into the real world pressures exerted on them, and within their own psychology of their needs (and fears) and how this patterns their actions. Using game theory, we put the different logics of the donor countries (and cultures) and the recipient countries (and cultures) into the structure of a model, to see what the different choices, beliefs, and outcomes are of the "two" sides and how they relate to each other in ways that undermine sustainable development policy.

This thinking leads us to the following: It may be that international approaches to sustainable development are, ironically, failing to address one of the key motivations preventing sustainable development: the insecurity that leaders and their publics (at the level of individual cultural/ethnic groups and of countries/ nation states) feel as a result of real or imagined threats from more powerful groups. These insecurities create an incentive to more quickly exploit their resource base to save it from others, either to give it away as a "gift" (for instance through trade deals or even overt bribes) to prevent invasions or to use the profits for military might, economic power or prestige, or to expand population and consumption to generate larger, better resourced armies. Ironically, it appears that the "security" brought by globalism is hiding continued underlying fears regarding cultural and country resources. For the majority of the 6,000 cultures on the planet that were (by definition) sustainable within their resource bases and were not "dependent" on outside trade or imperialism to meet their consumption needs,1 it actually preys on these insecurities in ways that promote sale and exploitation of resources rather than sustainable protections in each country or cultural ecosystem. The free flow of resources through globalism creates a downward spiral that makes resources more vulnerable and makes cultures and countries even less sustainable, thus undoing the "security" globalism is believed to be creating.

The Science of Sustainable Development and the Discrepancy between International Agreements and Actions

Governments of developing countries, international development organizations, international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and even scholars and scholarly journals that teach modern approaches to environmental protection, all use the word "sustainable development" today, but with widely varying (often directly contradictory) applications.

Our analyses of the agendas of several categories of international organizations, using an indicator we developed based on international standards, demonstrates that few of these actors actually apply the agreed principles of sustainable development in their country programs (Lempert & Nguyen, 2008). Indeed, we developed this sustainable development indicator for international development agencies--as well as several other accountability indicators that are now under review or in press--as ways of holding the international community accountable to its own agreements and standards. Our assumption was that a few organizations lacked awareness or knowledge. What we found was that lack of compliance was rampant and indicated widespread system failures (or undermining of the international system and standards on the basis of some other logic). In the area of sustainable development, this failure seems to be more out of an ideological blindness than a lack of understanding, because it extends to environmental organizations and to scholars teaching environmental policy that should have clear goals and targets. Even in the industrial world, others have noted that investment policies in new technologies have yet to be tied to sustainability goals and have had to call for approaches to education, research and development, and energy savings that should be obvious (Shellenberger & Nordhaus, 2004).

The principles that underlie the work of environmentalists and development experts, and that have long been rooted in international agreements, are easy to state and we briefly cite them again here for clarity.

The concept of sustainable development is a simple one. According to Principle 8 of the Rio Declaration, sustainability is a balance of consumption (the number of people and the amount of consumption per person) with resources (a fixed amount of resources and an amount of productivity per resource that ensures the resources are replenished and not used up for future generations) (United Nations, 1999). This equation is taught in the basic text of environmental science as the "IPAT" equation and is among its most fundamental precepts. We restate it in one of its simple forms (Ehrlich & Holdren, 1971; Commoner, 1972).

Population x Consumption = Resources x Productivity / Resource

The idea of a multigenerational balance is not only recognized in the Rio Treaty and in the scientific concept, but also in treaties on the rights of the child to resources and culture, along with other basic human rights accords and declarations (United Nations, 1989).

At the same time, international laws recognize that there is no one kind of system or cultural approach that best meets this balance. The concept of "culture" is a protected right to choose the level of consumption and technology that achieves this balance consistently with a resource base. Some of the world's 6,000 cultures have chosen to keep their productivity and consumption low. By international law, they are supposed to have the protected right to do that along with several other "guarantees" (United Nations, 1948; 1966; 2007; Lempert, 2010). Some cultures choose to maintain their technology without innovation and have a protected right to do so. At the same time, a few of the world's cultures--those that are urban and the most powerful on the planet--choose to try to keep improving productivity, so that productivity and consumption both grow. By international agreement, the rights of all cultures are equal, with neither type of approach to infringe on the rights of the others and with none qualitatively "better" than the others. This culturally pluralistic approach to sustainability and equity is a basic bedrock principle of the international legal system, not to be overridden by any other political or legal or ideological determination. Any other definition or understanding of the agreement would be contradictory to the principles and rights intrinsic to this framework.

It is also important to note that this definition of sustainability is not specific to any faction of the environmental movement or linked with a particular environmental ideology. This is not the viewpoint of the "dark" or "light" or "bright greens" or a part of the "deep ecology" movement or any other classification of actors in the environmental movement. The sustainability principle does not offer a blueprint for individual cultures on how to achieve sustainability and what kind of environmental quality each culture needs to protect. It simply sets the goal of balance and establishes the factors to be measured. It is a universal definition from the science of ecology and social science that is also recognized internationally as a common standard.

How Development Organizations and Others Interpret (Redefine) the Principles of Sustainable Development

Despite the simple and clear scientific definition of these concepts, they are largely abandoned in application by development organizations, international donors, and wealthy countries. In many cases, the very words "sustainable" and "development" have been distorted well beyond the actual meaning as established by the international community in the Rio Declaration of 1992. Indeed, there may not be a single developing country in the world where an international organization (e.g., global development bank, development agency, donor, or NGO) actually offers a sustainable development plan for the country or for its cultures, following the guidelines of the Rio Treaty. In fields outside of the natural sciences, such as economics and political science, scholars have also offered arguments to justify the disregard for the scientific standards and the international agreements that support them based on cultural logics of imperialism and hegemony, psychological theories of leadership behavior, and other frameworks.

Many readers may already agree that the standards of sustainable development have been abandoned or twisted by nation states, international donors, implementing agencies (including those who claim to be doing sustainable development and environmental protection), and scholars. Ingolfur Blühdorn (2007) and his colleagues have recently commented on this phenomenon as a pervasive attempt to create almost a religious belief in a technological "magic" that will lead to sustainability, with no scientific basis or actual plan based on empirical fact. They refer to it as the "politics of unsustainability" or "simulation." Before considering why we think this has occurred, we offer this section to help readers to consider the extent of these gyrations. The efforts to distort approaches to sustainability seem so widespread (and so perverse) that they suggest an underlying psychological motivation at work, rather than simply a misunderstanding or lack of knowledge.

In international organizations like the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), for example, where sustainable development is still defined as the target goal in current program statements and where the legal mandate to uphold international treaties resides, the standards behind the definition have largely been abandoned and replaced in recent years (UNDP & UNFPA, 2007; Lempert & Nguyen, 2008). Previous UNDP administrator James Gustave Speth, an environmentalist and lawyer, directed the agency during his tenure (1993–1999, immediately after the signing of the Rio Declaration) to follow treaty obligations to protect cultural choices and diversity to achieve sustainability at their culturally and environmentally appropriate levels of consumption and population. There were no requirements that cultures copy the approach of urbanization or international trade, since these would violate international rights laws (United Nations, 2000a). Yet these directives now appear to have been abandoned by UNDP leadership and by the United Nations (UN) system and replaced by a checklist of development goals that almost entirely focus on only one of four factors in the equation; productivity (and largely in short-term sales, measured by gross domestic product (GDP), rather than in actual productive efficiency in the use of resource wealth), using a common set of technologies. It appears that most other development organizations today reflect the same distorted understanding and reduce the equation to the same single factor.

The distortions among development organizations include the following three types of reinterpretations of what sustainability means in the context of development assistance.

First, many international NGOs now substitute a focus on short-term "poverty reduction" through high productivity for sustainability. They measure their target as relieving current symptoms of poverty or achieving equality by overcoming differences in relative consumption between different cultural groups. Or, they define the goal as employing foreign technology for more efficient use of resources. The NGOs' view of equality is one of homogenization, which, they suggest, is superior to upholding internationally protected cultural or environmental rights to promote long-term sustainability of cultures within their resource bases and their own technologies. The basis of the pluralistic principle of sustainability, and the reason it was originally chosen as the key goal by the international community and reiterated by UNDP under Speth, was that this priority approach actually eliminates long-term poverty within each cultural context through creating a balance of population, technology, and resources, but now even the UN abandons it. At best, organizations now include sustainability as just one of eight factors on a checklist of the UN system's new international Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that are no longer linked in an equation. The priority is short-term poverty relief that may be funded through exploiting resources, making long-term poverty reduction and sustainability impossible. On the UN system's website for the MDGs, sustainable development is now listed as the seventh of eight goals and is redefined as "environmental sustainability" (United Nations, 2000b). There are no factors for reducing consumption or population or protecting cultural choice and rights anywhere on this list, though they were and are the guiding factors in achieving the other goals (United Nations, 2000b). Some of the most recognized NGOs, like Oxfam, also have abandoned the sustainability equation. They substitute the same single factor--short-term productivity growth through transferring foreign technologies into different cultural contexts--for sustainable development. Moreover, they do it at the expense of resources and cultural rights to choose levels of consumption and technology that fit resources. Oxfam's website for one of its major new initiatives, as but one example, even defines "[e]fficient uses of resources" as an economic productivity measure "per project dollar spent," no different from the terms a bank would use (Prosperity Initiative, 2008).

Second, international donor organizations have not only sought to focus on increased productivity of recipients rather than on sustainability or protection of rights, they have redefined the term "sustainability" such that it avoids the Rio Declaration and other treaties entirely. In most international development project documents of organizations such as those comprising the UN system, the European Commission, or country donor agencies such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), sustainability is redefined as a measure of whether the "results of a project are sustainable" and continue in subsequent years for an indefinite period. This perverse logic is now at the basis of their approach even where that includes increasing productivity that causes natural resource depletion, and even where projects undermine sustainable development in accordance with international law.

Finally, country governments mistakenly redefine "sustainable development" in a third way. They refashion the term as "sustainable growth," meaning the continuation of profits for merely a few years, without any measure of long-term balance and protection or continuity of people and communities in their environments over generations. This is also in direct contradiction to the principles that they agreed to in the Rio Declaration.2

Academics in fields such as economics also now ignore and redefine the foundational scientific principle of sustainable development in ways that reinforce the justifications offered by international donors and development agents. Rather than recognize the international treaty obligations that respect the rights of all cultures to choose their own levels of technology and consumption that fit their individual environments and to achieve sustainability in ways that promote and protect human cultural diversity, they argue that there is really only one type of viable path toward sustainability. As other critiques have noted, many economists distort the concept of ecological modernization offered by sociologists to describe one possible sustainability solution for industrial societies (Huber, 1982; Mol, 1995). They make a single choice--industrialization, urbanization, and globalization in a common world system monoculture--the objective of sustainability (Mol, 1995). Mainstream economists and political scientists continue to contend, in contradiction to the fundamentals of Darwinist evolutionary biology, human biology, and anthropology (Steward, 1955; Sahlins, 1960) that there is a single evolutionary path of development and of human systems.

This denial of the established principle of cultural adaptation (adaptive radiation) and evolution reasserts the nineteenth century view of a "linear" evolution of cultures in their relations with the environment. This rewriting of evolutionary biology and human cultural evolution mandates urbanization and industrialization as the only possible choice for all peoples. Development becomes a slogan justifying the role of technologically advanced and powerful actors to use their knowledge to push all other societies onto this single path. One might argue that this is a new form of the attack on evolutionary theory by the church that helped to sustain the spread of European imperialism and its ideology of a "civilizing mission" over "primitive" natives, despite the rise of disciplines like ecology and anthropology that offer scientific explanations of how adaptation and survival are best promoted (Lempert, 2010).

A related argument offered mostly by economists is that there is only one acceptable choice for all the globe's cultures of how to balance the sustainability equation, through an approach called "weak" sustainability (Solow, 1993). In their view, balancing the equation requires a set of fixed choices for continuing growth of technology and consumption. It accepts human ability to mechanize and control the natural environment and all of its processes and implies the ability to measure all of them in monetary values. According to proponents of "weak" sustainability, "destroying" or "controlling" and monetizing nature is a political choice that is preferable to protecting nature itself; the goal of "strong" sustainability. They object to the "strong sustainability" approach that takes into account human qualitative valuations of nature, different methods of measuring value, and interaction with the natural environment as outside of their single measurement system predicated on monetization as the standard of value. In fact, monetization is also a political and ideological choice that empowers those who hold the money. These scholars consider the human construct of money and the way it defines value to be a more universal measure than the scientific equations from other fields that they say should be discarded as political (Ayres et al. 1998).

Generally, economists and political scientists frame these arguments using a theoretical basis rather than an empirical test of historical sustainability and collapse. They do not subject their theories to the evidence of multiple cultural and environmental contexts through human history demonstrating how population, consumption, and technology pattern the sustainability and the collapse of cultures and civilizations in their resource bases (Tainter, 1990; Wilson, 1998). Among the theories economists use to support their belief in sustainability without directly applying the IPAT equation is a posited relationship between economic growth and inequality applied to the environment as "the environmental Kuznets curve" (Kuznets, 1955; Stern, 2003). This curve suggests that initial increments of economic growth damage the environment, but ultimately in its intermediary and advanced phases leads to environmental improvement. In fact, Kuznets never wrote about the environment or about sustainability at all. Yet, economists have used his optimism about equality to apply this simple curve to defend against other criticisms of their monocultural model of economic growth, including concerns about sustainability and economic collapse (see, e.g., Grossman & Krueger, 1991; World Bank, 1992). Economists who support globalization use the curve to suggest that all forms of economic growth that currently damage the environment and appear unsustainable will ultimately result in a return to equilibrium with the environment as economic growth and exploitation continue.

There have now been twenty years of argument over the environmental Kuznets curve with almost every empirical environmentalist and anthropologist demonstrating that it does not stand up to data. Recent studies by social scientists show that improvements in ecoefficiency (the ability of production technologies to exploit lower amounts of resources per unit of production) have so far proven insufficient to compensate for the overall increase in consumption that follows with higher levels of affluence (York et al. 2005). There also seems to be a fallacy in the thinking that higher consumption creates incentives for higher investment in research that then leads to efficiency improvements. The current incentive system in industrial societies appears to lead only to increased competition for the planet's resources under the cloak of spurring a future fantasy technological breakthrough that will lead to sustainability (Nguyen, 2008). These criticisms are also bolstered by a line of historical studies demonstrating how civilizations with a similar single minded focus on productivity follow patterns of collapse rather than long-term sustainability (see, e.g., Tainter, 1990). While the principles of biology and physics suggest multiple levels of stability and sustainability that are context specific and suggest that single, homogeneous complex systems are the least sustainable, those supporting globalization along a single path use Kuznets to assert that their approach is the most robust and sustainable (Stern, 2003). It appears that continued support for Kuznets is based on wishes more akin to religious belief than scientific argument, since it is not grounded in empirical reality, as at least one group of leading economists has argued (Arrow et al. 1995).

We do not claim that the strong sustainability or the weak sustainability approach for an already industrialized culture is the correct one. Some types of economic growth are obviously sustainable since all human cultures represent some use of technology and there are still humans on the planet. We are simply noting that weak sustainability proponents are largely advancing arguments inconsistent with empirical science and the international legal agreements that uphold the rights of cultures to proceed in ways that promote human cultural diversity, competition, and adaptation. Most supporters of the strong sustainability approach whom we meet in our work at least respect the international treaty obligations and recognize the scientific standard that the agreements protect as the one to follow. Meanwhile, most economists and political scientists who support the weak sustainability approach have chosen to substitute their own definition of sustainability in a single, uniform vision for the planet that discards the four factors in the sustainability equation and reduces the idea of balance to an ideological faith in productivity alone. Most civilizations and human cultures that have existed in human history are now extinct, a phenomenon often attributable to their inability to exist sustainably with their environments. Thus, we wonder what logic would lead both practitioners and many academics to unite in evading the Rio Treaty standard that reflects the scientific and technological view of progress that they claim to believe in and that is supported by the international legal system that they created to protect their own interests.

In our view, the distortion of the language of sustainability by many contemporary actors is Orwellian. We search deeper for explanations for what appears to be contradictory behavior.

A Logical Hypothesis for Why Development Actors Seem to Abandon the Agreed Standard of "Sustainability"

Generally, when there is a conflict between a written law and its applications, the contradiction is attributable to discrepancies in the interests of different groups. In the case of sustainable development, however, almost all actors seem united in both supporting the scientific and political standards and in finding creative ways to evade them. Achieving sustainable development and dealing with international environmental crises seems, by its very definition, to be in the long-term interests of every actor, from the developed/urbanized countries and cultures to the nonurban, and including development organizations. How is it--with global warming and environmental pollution invading bodies with chemicals and radiation, flooding homes, and destroying the planet's natural systems--that the very organizations responsible for sustainability would turn their backs on their agreements and twist the concepts that they well understand into meanings never intended? The logical explanation is that a hidden or unexpressed set of beliefs is creating a contradiction. It may be a simple truth that is too difficult to openly express, perhaps even a taboo. In this case, the contradiction appears to be between an ideology of sustainability that requires a balance and one of productivity that undermines this balance. Can this contradiction be resolved?

Before offering our hypothesis of the actual motivations, it is important to examine what the different international actors are doing in place of sustainable development. Since the actual behaviors that international organizations and countries are following are not random, they must presumably be following some kind of logic and pattern that can be modeled. If we can expose this "deep structure" of behaviors and listen to what actors say directly, in private conversations, about their actions, we can offer a hypothesis about this alternate logic.

Each of the three development actors (international NGOs, international donor organizations, and country governments) that have distorted the scientific definition of sustainable development appears to have a different motive, but their behaviors may also reflect a deeper reality. What they have in common today, as in the past, is their unwillingness to recognize the free choice of cultures/countries to their own development approaches and their internationally protected right to these choices. What appears to be underlying is an unwillingness to recognize a related right: that of protecting the full range of assets of each country/cultural unit (e.g., resources, people, cultural heritage, and social and political organization) that are the basis of sustainable human development.

"Development" organizations (international NGOs) have transformed the interrelated goals of equality and sustainability and have substituted another definition that distorts the objectives of sustainability. Their definition of equality is to bring everyone up to the same standards of consumption by replacing cultural differences with imported technologies that will increase productivity, keep population rising, and promote international trade and urbanization across the planet. In their view, the way to achieve equality is not to protect diversity or even to seek to reduce consumption while promoting economic distribution (sharing) from the wealthy. The aim is to raise everyone up to the same level. This is not very different from the historical goals of "Marxists" and the Soviet Union, or of China today, or of the western missionaries who spread throughout the Third World in the colonial era. It is a common ideological approach shared by global powers. For example, Gus Speth (2008), one of the original champions of the sustainable development standard, also falls into this contradiction. He links equality (through growth), democracy, and environmentalism as the three essential pillars of development, though he recognizes that they may actually be impossible through growth.

International donor organizations and governments everywhere appear to be following a different logic from the one of long-term economic benefit and cooperation that political scientists have long modeled. In the 1960s and 1970s, development scholars created "dependency theory" to explain that "development" was really a new form of colonialism and external reliance, driven by the desire of major powers for markets for their goods, cheap labor, and ability to exploit resources (Gunder, 1967; Wallerstein, 1974). Contemporary proponents of this view contend that this pattern is still occurring today, and that this ideology continues to trump the dialogue on sustainability (Korten, 2007). These critics add that many experts who claim to promote sustainable development will never address consumption because the underlying goal of development is to promote interests antithetical to sustainability, to benefit business and increase aggregate consumption. They also contend that consumption is not addressed because higher population promotes greater consumption and keeps wages low for foreign investors seeking reduced product costs. They argue further that environmental standards will never really be enforced because the underlying logic of development is to shift production to poor countries that are too weak to impose environmental protections so that the result is to export pollution and environmental damage.

Those social scientists who accept the view of dependency theory recognize the motives of corporate interests and of empires whose very basis for survival undermines the concept of sustainability. These imperial cultures and interest groups within them exploit nonlocal resources rather than live sustainably within their own resource bases. Empires overuse their resources and dominate other cultures, until their empires ultimately collapse and are replaced (Tainter, 1990). What makes this model of the world difficult for sustainable development theorists to confront is that it does not fully explain the behaviors of developing countries or the global trade system that has emerged.

If the struggle is really between wealthy countries that are exploiting "developing" countries, what is hardest to explain is why the countries and cultures who fought against colonialism to protect their own cultural prerogatives and developmental priorities would also abandon the sustainable development standards and international laws that would protect them. Why would countries and cultures that fought against colonialism and which sought to eliminate colonial institutions and ideologies, now embrace a monolithic view of development? Why would they embrace the very institutions and ideologies that they fought in the past? Why would they avoid incorporating the simple sustainability planning mechanisms--the kinds of measures of assets and consumption needed to assure sustainable development as the very essence of what government planning is supposed to do at the local and national levels? Why do their agendas continue to be investment portfolios as they were in the colonial era, and that are brought to them by international banks and organizations in the form of loans and policies that they should be free to refuse and to replace with more sustainable alternatives? Why do they still base success on sales and income measures (what they export) and on productivity, rather than assets, protection, wealth, or quality of life?

While we subscribe to dependency and world systems theories (Lempert, 1995), we think a corollary may be needed to explain the fundamental internal contradiction between the growth and dependency model of the global system and the standards that it has simultaneously promoted for sustainable development but refused to follow.

One aspect we have considered is how power balances among different groups influence their motivations. Our previous research provided a clue to understanding contradictory national behaviors (Lempert, 1995; 1998; 2000; Lempert & Nguyen, 2009) and we draw from it as well as our field experiences in applied development work with governmental leaders over the past three decades. In looking at how international actors have redefined sustainability in terms of equality that homogenizes every culture to the same level of consumption and technology, in violation of international rights protections and sustainability principles, we noted how this distorted view of equality has been common to both capitalist and communist societies that have industrialized.3

An Hypothesis: The Missing Link between International Security and Sustainable Development Policy

Before even addressing the motivations that might be at work in causing almost every country in the world to choose approaches that evade what is arguably in their long-term self-interest (sustainable development), what struck us immediately is how well it could fit one existing social science framework of looking at seemingly contradictory behaviors that is applied to international actors as well as individuals in competition. That tool, coming out of game theory, explains what is described as the "Prisoners' Dilemma" and it seems to apply perfectly here. Moreover, what game theory does is show how seemingly illogical behaviors are actually perfectly rational when one understands that the motivation of international actors is actually fear of each other. Indeed, the missing link in understanding evasion of commitments to sustainable development seems to be the underlying but real fears that countries and cultures have of each other and that are only being addressed in the international system in an effort to make everyone "the same."

This may be the classic case for using a "Prisoners' Dilemma" framework. Two opposing logics of behavior appear to be at work and the contradiction is between long-term interests (environmental sustainability) and short-term interests (productivity, growth, and poverty reduction through short-term treatment of symptoms). The choice could work against the self-interest of some actors (i.e., less developed countries and cultures) and the logic seems driven not by positive choice but by an avoidance or fear driven response. Political scientists have long modeled contradictory behaviors using a game theory model in which actors make short-term choices that contradict their long-term goals because of their fears of what other actors might do (Morganstern & von Neumann, 1947).

This model seems to fit what is happening in the international system today with respect to sustainable development. Furthermore, we have heard statements, both in private conversations in our work and in closely reading the media and speeches from government leaders that suggest their approach to sustainable development is actually driven by their short-term fears of actions by major international actors. In their view, short-term decisions to pursue unsustainable growth actually stem from concerns about what they must do to protect their short-term security. From the perspective of government leaders, and from citizens who may also fear more powerful countries, this behavior may actually be quite rational, though it may make sustainable development impossible.

Perhaps the best statement of what is happening comes from leaders of governments whose rhetoric has radically changed during the period prior to and after independence. We have worked for years with Southeast Asian, Latin American, and Eastern European governments and with NGOs. Their statements about their choices help to make the problem clear. They suggest the security threats that countries still face in the global order really drive their choices on sustainability and that environmentalists and environmental policies are not addressing this concern.

For example, the Vietnamese government claimed to have fought a revolution to protect the rural way of life and the country's culture or spirituality and simplicity. Now, by contrast, the government stresses how urbanization, globalization, and trade will promote wealth and power and how these are its central goals. Public statements define economic growth as closely linked to higher military spending and security, with sustainable development not even mentioned (Communist Party of Vietnam Central Committee, 2006). If this is the goal of the leaders of the country whose majority nationality represents the thirteenth largest population group on the planet, and its priority is to keep expanding population and consumption, even at the risk of destroying its resources and traditional culture, they must have some other very important overriding motive. They make it clear that that motive is security. Undoubtedly, Vietnam's recent historical experience of being bombed by the French and the Americans and invaded by the Chinese is at work here.

Government documents, conversations, and press releases reiterate the fear of being invaded and having the country's resources taken or destroyed by more powerful outsiders. The opening sentences of national economic reports directly link economic policies with the need for security and the lack of international stability (see, e.g., Communist Party of Vietnam Central Committee, 2006). Though it might be easy to dismiss that motive as paranoia, Vietnamese leaders see a world where superpowers target foreign leaders and resources. Countries like Iraq that are similar in size to Vietnam, or Afghanistan that are even smaller and weaker, are not a direct military threat to the superpowers but are a source of resources and sites for the transit of resources for those countries to exploit. Those smaller countries are a threat only to the goals of the larger countries for consumption and resource exploitation (Sampson, 1975). Vietnamese leaders see a world where neighboring China continues to invest in weaponry, keeps its hold over Tibet, calls for control of Taiwan, and uses its military and economic power in Myanmar as well as in Africa where it seeks resources. In the view of Vietnamese leaders, their development choice is constrained to one of trade relations and the need to purchase weaponry in response to perceived threats, rather than sustainability. At the same time, these leaders today, as in the past, view population growth, particularly of males, as their greatest asset in long military conflicts and in ability to protect land (see, e.g., Hendershot, 1973) despite the consumption of resources and competition that it also creates.

Meanwhile, in neighboring Laos and in small countries of Eastern Europe that have been bombed and overrun by larger powers in recent history, the incentive to join the World Trade Organization and to agree to the exploitation of their domestic resources has been described to us in private meetings as a way to appease foreign interests. Leaders constantly call for trade as part of their strategy of peace and friendship, stressing their fear of future attacks. The deals they make for mining, hydropower, and land sales for production of export crops like tobacco and coffee force their own minority peoples out of their ecosystems (agricultural land, waterways, and forests), sell their resources, and decimate their own industries as they open the door to foreign imports. They recognize that these are not strategies for sustainable development, or even for protection of their own cultures. At the same time, these leaders constantly note how much better off they are living in peace and without the fear of outside attack. This is not a return to trade systems of the past where local cultures maintained their resources and systems of production and traded in local products. Moreover, the leaders we meet with in our work advising on and in researching the history of policies and practices are very much aware of the difference. They see themselves accepting the return of foreign powers (and often seek to play off those powers against each other) as a forced choice in which their countries, and sometimes they themselves, are under risk if they do not agree. In many cases, they also recognize that they are in power in their own countries because larger powers want them there as intermediaries to extract resources or to serve foreign investment and they serve that role under pressure. They are giving away in sales and trade what they are unable to protect militarily, while turning their countries into production zones for rubber, coffee, and the very same exports demanded during the colonial era.

In this article, we focus on presenting our hypothesis and theory, rather than on recounting the numerous conversations we have had with government officials, many of whom suffered directly from foreign invasion of their countries.4 Nor do we wish to belabor the parallels between the statements of the countries that colonized them and their own statements with regard to exploitation of their minorities and resources now that they have taken over the former colonial systems. Among these meetings, however, perhaps the most poignant was one held with former Philippine President Diosdado Macapagal (and father of recent President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo) in private in his home. In describing decisions he made as President, he referred almost in tears to what the United States "could do" and did do, including assassinating leaders in neighboring countries and bombing millions of people from Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

When looked at overall, across the globe, the irony of globalization is that it is presented as a way of reducing tensions and promoting security and choice (Deudney, 1990). Rather than decreased military spending, globalizing processes are correlated with the increase and continuation (if not exacerbation) of national (and cultural group) insecurities. For instance, global military spending is up 45% during the past decade and represents 2.5% of global GDP, while resources decline (Agence France Presse, 2008). Although exploitation of another country's oil or minerals or labor or markets is not the only motive for war, classic studies of war have recognized that resource exploitation is a motivating factor (Hobbes, 1902; Prebisch, 1950) and that even in countries that promote ideologies of technological growth, any kind of imbalance between consumption levels and resources, or between productive needs and resources, can be a cause of war even between trade partners (Kelly, 2000).

While the current dogma of those supporting globalization is that trade makes countries less likely to go to war and that it renders formerly unsustainable countries that were dependent on resources less militaristic, the debate reverses cause and effect. Countries may choose trade as a way of being protected against direct attack and of leaders maintaining their positions as intermediaries. It is not that they are freely and equally choosing trade to resolve the underlying conflicts. If this were the case, one would expect globalization to reduce pressures on cultural extinctions by promoting more rights and freedoms that should come with trade, rather than accelerating internal colonialism and destruction of cultures.

While environmentalists and peace activists have linked the issues of environment and peace, they have not paid enough attention to the concerns of resource security as a basis for sustainable development.5

It is true that many "environmental" and "peace" activists have developed linkages with each other in their policies and ideologies, largely from the consumption side, and partly from the institutional side in looking at growth (Global Greens, 2001). They have called for moving toward renewable energy as a way to shift government policies away from the exploitation and capture of oil and other resources on which dependencies are linked with pressures for war. They have also called for lowering consumption as a way to limit demands and pressures on resources.6 Some also link corporate behavior and motives for profit or control to environmental damage and seek to change the global ethic and behavior of corporations (Korten, 2007). The environmentalist ethic of peace, consumption, and fairness, linked to a love of nature, has also partly been presented to developing countries in seeking to change environmental consciousness. But the apparent rejection of this approach in developing countries suggests that other forces or psychological mindsets (cultural and cognitive factors) may be at work that environmentalists are not addressing, notably the need for security. Overall, environmentalists have not explicitly linked the idea of resource security with concepts of environmental justice, peace, or equity.

Implications for Development Policy of the Delinking of Security and Sustainability Policies

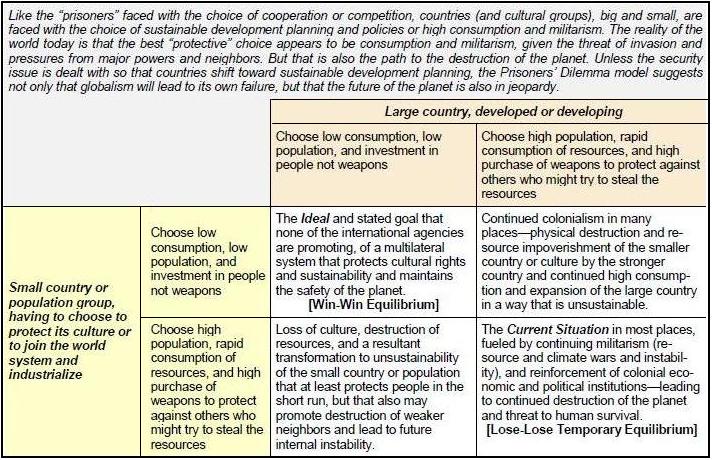

The contradiction between the long-term goal of sustainable development, through cultural pluralism that allows cultures to choose ways to coexist with their environments, and the short-term goal of groups to protect themselves, through high productivity to fund militarism in ways that require abuse of their resources, seems aptly described and modeled within the framework of the classic Prisoners' Dilemma, shown in the matrix (Box 1). Like other prisoners' dilemmas, there may not be a way to change the choices of international actors to support long-term systems and standards for sustainable development, because it is in their short-term interest to make the very choices that promote unsustainability. The implications of this are severe and ironic. The global system that proclaims a path to harmony, pluralism, and sustainability may actually be destabilizing itself.

Countries would choose sustainable development policies if they believed that they lived in a safe world. However, despite all of the rhetoric about how much safer the world is today because of globalization, the contemporary global trade regime seems to be a symptom of international threats as much as of a faith in the ability of countries and cultures to choose independent paths (Korten, 2007). The legacy of the twentieth century continues in global conquest by the major powers in Iraq, Chechnya and the Caucuses, Sudan, Papua, and elsewhere, and it maintains the reinforcing spiral of insecurity that leads to more militarism both to protect and to appropriate resources.

If this theory is true, the preferred solution to the Prisoners' Dilemma seems unlikely to be implemented. According to game theorists, cooperation results from repeated interactions by different parties in a way that recognizes and reinforces mutually shared interests (Axelrod, 1984). At the international level, there seems to be little precedent or movement toward this kind of cooperation or bargaining. The current global distribution of power is skewed and the international system has been unable to restrain the major global powers from using military force to expand their private interests. In fact, the most destructive and negative outcome can be described as a Nash equilibrium, a stable solution that no nation sees a benefit in trying to change, even though it ultimately leads to the worst possible outcome (Nash, 1951).

In our experience with governments in developing countries, their inability (or unwillingness) to protect the environment is not so much due to a lack of ecological consciousness, but an institutional framework of national security fears that remains linked to colonial institutions of resource exploitation and high consumption to fuel the military and police apparatus. Given the reality and/or the psychological depth of these security fears, as a legacy of colonialism and a continuation of global competition for resources, the appeal of environmentalism and sustainability may not only be weak motivators, but may actually be irrelevant.

The elephant in the room that is driving the dilemma appears to be the failure of the international system to provide any real security that natural and cultural resources will not be destroyed by invading armies, destabilization, or political systems of control. The only real resistance continues to be attempts at counter power through the kind of destructive growth that can buy weaponry or decelerate the pace of destruction by giving away resources or accommodating foreign voracity as a form of slow appeasement.

In our view, the real problem that sustainable development experts have is not about convincing people to love the environment or to care about their children, which is the way that environmental awareness campaigns are now structured. All human beings have a natural inclination to revere nature. According to evolutionary biologists, not only have we coevolved with nature, but we are biophilic and naturally seek to protect our own genes (our children) and our environments unless we are taught or conditioned by some other motive (Fromm, 1964; Wilson, 1984). There is not much sense in trying to tell people what they already know in the same way that many health campaigns seeking to make people aware of the harms of smoking or poor diets are ineffective. The problem may not be awareness. It instead may be a Prisoners' Dilemma in which choices are the most "rational," but nonetheless lead to the most destructive outcome.

Box 1. "Prisoners' Dilemma" of Nation States

|

Theoretical Framework for Future Testing

If dependency and world systems are extended to include the concept of resources, it appears that the current approach to globalization is a classic prisoners' dilemma that not only cannot lead to the long-term equilibrium of sustainability, but that may potentially worsen the planet's current environmental problems, thus leading, ironically, to the disintegration of the global system. If this is correct, can environmentalists or developed countries do anything to change this fate, or does it have to transpire in accordance with its own inevitable logic? This is the question that we pose. We restate our findings and some of the possible--and frightening--implications below.

Sustainable development by definition requires an approach that looks at the ability of cultural groups to subsist within a given resource (asset) base and that protects this right. It is these standards that have been established in international law. At the same time, the linkage between security and those asset bases has been blurred by ideologies of free mobility of resources (capital and labor) and specialization (comparative advantage), as well as ideologies of the current world order of globalism and trade that is seen as the way to overcome past nationalist conflicts and colonialism.

The global system is apparently locked into a set of choices that is leading to the outcome that no one would choose, a downward and irreversible spiral toward a perverse Nash equilibrium. Empirical evidence suggests a vicious cycle between military insecurity (fear over resource theft and the need to protect these assets) and environmental unsustainability. Militarism and appeasement feed environmental destruction by those seeking to take resources and those having to sacrifice part of those resources as the price of defense, while environmental (resource) crisis feeds war.

Rather than considering the destruction of the environment as a cause of war over dwindling resources, there may actually be a more complex relationship--a vicious cycle--in which the need to secure resources may actually be driving their overexploitation as a means to increase economic and military strength. This iterative process further drives competition over dwindling and disappearing resources. Moreover, this positive feedback loop, supported by ideologies and institutional structures that are the legacy of colonialism throughout the world, may itself be a Nash equilibrium that is now impossible to change because it is self-reinforcing through "rational" choices by governments and cultural groups. This outcome may also explain the "rational choice" of countries to begin to prepare for climate wars and further resource competition rather than to agree to the very frameworks for sustainability of the planet that are, ironically, also the key to maintaining globalization. In other words, the current approach to globalism does appear to be promoting its own breakdown because of a built-in contradiction in the approach to sustainable development.

While there is an emerging view among certain parts of the green political movement that sustainable environmental policies must be linked to movements for international peace, and a recognition that the endangerment of resources (productive resources and human populations) may provoke future climate and resource wars (Kaplan, 2001; Homer-Dixon, 2006), it does not go far enough. The important conceptual connection may not only be to peace, but to overall security for small countries and cultures so that they may psychologically perceive (both actually and in terms of overcoming any "irrational" fears) that their resource base is secure.

In development policies, the unaddressed root causes of unsustainability appear to be the institutions and the psychology of colonialism that remain in former colonial and former colonized countries. This legacy may be the real source (or symbol) of failure on the part of international development organizations to promote policies that can truly be called sustainable development, that could protect cultural diversity and ensure long-term balance between each cultural group's population and consumption with its environment and technological capacity. If our theory is correct, not only is the sustainable development policy approach wrong (or irrelevant), but there is considerable doubt whether these fundamental causes can be changed. It may be more likely that global environmental crises will only augment fears and insecurity in a vicious cycle that reinforces the problem rather than fosters a solution. Moreover, given this system, it may be "rational" behavior for nations and ethnic groups to exploit their resources as part of preparations for future resource and climate wars that the global system has made inevitable.

Unless sustainable development planners are willing to confront the elephant that remains in the room, and link global security issues and rights protections for small cultures and developing countries with sustainable development planning, there is little hope that approaches consistent with scientific standards will be adopted and few prospects for a sustainable human future. At the same time, there is a question as to whether those of us working in this field have the political acumen, skills, or courage (with donors and developing country governments) to add these approaches to our repertoire. Several recent studies of the United States and the former Soviet Union for example, suggest that militarism is so embedded in the culture of economic superpowers that they cannot transform themselves until the empire itself collapses (Lempert, 1995; Johnson, 2004: Bacevich, 2005).

The implications of these circumstances for the planet and for sustainable development approaches could be staggering.

Notes

1 These 6,000 cultures are as measured twenty years ago using language as a proxy for culture, with possibly hundreds already disappeared since then according to measures and projections (Krauss, 1992).

2 In its current formulation of international development policy, for example, even Sweden makes the claim that "poverty" is the result of lack of economic growth rather than lack of sustainability. The country establishes "sustainable growth" as the basis of its development policy without even mentioning the term "sustainable development" (see Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs, 2010).

3 An earlier article (Lempert 1998), explaining why Karl Marx sought an equality that was not simply economic but that destroyed cultural differences (and political choices) in mass society, offered a cultural explanation. This work suggested that Marx's personal experiences as a German Jew, fearing ethnic violence (and genocide), largely motivated him and other Jews in Europe to promote ideologies that would eliminate ethnic differences and thus the violence (and fear) that came with it. The article describes how similar fears by minority scholars and practitioners today have distorted their scholarship and motivated international agendas for "equality," including suppression (and destruction) of cultural differences, even of one's own culture. Indeed, it is when describing the fears of leaders of developing countries of foreign invasion, and even assassination, if they do not agree to certain policies of globalization, that we hear direct echoes of the motivations of minorities advocating for "modernization" more than a century ago.

4 As a leading expert in legal development and governance, Dr. Lempert has worked as an advisor to government leaders including presidents, prime ministers, governors, parliamentarians, and judges in more than 25 countries over more than 30 years, both independently and for major international organizations and public and private donors. Prior to beginning professional work, he ran a number of university speaker series hosting active and retired international leaders and presidential candidates and also worked as a journalist interviewing national and international leaders on their personal histories and motivations. His professional work dates back to 1978, when he was on the staff of United States Senator William Proxmire promoting passage of the UN convention on genocide and analyzed the different concerns of leaders to support and enforce such protections. He has had private meetings with international leaders dating back to 1980 when he advised the Prime Minister of Mauritius on the country's politics and ethnic balances. His first meeting in the Kremlin was in 1990 during the Soviet era.

Ms. Nguyen has worked professionally for a decade as a legal analyst within the Vietnamese government as well as with government leaders of several countries in the Mekong region on environmental policies. She did research on sustainable development issues in northern and central Europe and interviewed local government and business leaders.

5 While the rights of farmers to land and the urban poor to credit have been considered fundamental to their economic security, and this is indeed part of a new global donor initiative (for "Legal Empowerment of the Poor"), even this kind of effort fails to address the larger issue of security of ecosystems and national resource asset bases (UNDP, 2008).

6 The ideology of the green movement has also linked food practices and peace by suggesting that vegetarian diets can promote more peaceful coexistence if not peaceful behaviors, drawing on the religious appeals of Hinduism and Buddhism (for animal rights and peace) as well as Judaism (Joseph Albo's Book of Principles from the fifteenth century).

References

Agence France Presse. 2008. Global Military Spending Soars 45% in 10 Years. June 9, 2008.

Allison, G. 1971. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. Boston: Little Brown.

Arrow, K., Bolin, B., Costanza, R., Dasgupta, P., Folke, C., Holling, C., Jansson, B., Levin, S., Maler, K., Perrings, C., & Pimental, D. 1995, Economic growth, carrying capacity, and the environment. Science 268(5210):520–521.

Ayres, R., van den Bergh, J., & Gowdy, J. 1998. Viewpoint: Weak Versus Strong Sustainability. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Papers No. 98–03/3. Rotterdam: Tinbergen Institute.

Axelrod, R. 1984. The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

Bacevich, A. 2005. The New American Militarism: How Americans are Seduced by War. New York: Oxford University Press.

Blühdorn, I. 2007. Sustaining the unsustainable: symbolic politics and the politics of simulation. Environmental Politics 16(2): 251–275.

Commoner, B. 1972. The environmental cost of economic growth. In R. Ridker (Ed.), Population, Resources and the Environment. pp. 339–363. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Communist Party of Vietnam Central Committee. 2006.

Report of the Executive Committee of the IXth Party Central Committee on April 10, 2006 on the Orientation and Tasks of Economic Development–5 Years from 2006 to 2010. March 30, 2011 (in Vietnamese).

Deudney, D. 1990. The case against linking environmental degradation and national security. Millennium 19(3):461–76.

Ehrlich, P. & Holdren, J. 1971. Impact of population growth. Science 171(977):1212–1217.

Fromm, E. 1964. The Heart of Man. New York: Harper & Row.

Global Greens. 2001. Global Greens Charter. June 7, 2011.

Grossman, G. & Krueger, A. 1991. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement. NBER Working Paper, No. 3914. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gunder, F. 1967. Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Hendershot, G. 1973. Population size, military power, and anti-natal policy. Demography 10(4):517–524.

Hobbes, J. 1902. Imperialism: A Study. London: Cosmo Press.

Homer-Dixon, T. 2006. The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity and the Renewal of Civilization. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Huber, J. 1982. Die verlorene Unschuld der Ökologie: neue Technologien und superindustrielle Entwicklung (The Lost Innocence of Ecology: New Technologies and Great Industrial Development). Frankfurt: S. Fischer (in German).

Johnson, C. 2004. The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy and the End of the Republic. New York: Owl Books.

Kaplan, R. 2001. The Coming Anarchy: Shattering the Dreams of the Post Cold War. New York: Vintage Books.

Kelly, R. 2000. Warless Societies: The Origin of War. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Korten, D. 2007. The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community. San Francisco, CA: Berret-Koehler.

Krauss, M. 1992. The world's languages in crisis. Language 68 (1):4–10.

Kuznets, S. 1955. Economic growth and income inequality. American Economic Review 45(1):1–28.

Lempert, D. 1995. Daily Life in a Crumbling Empire: The Absorption of Russia into the World Economy. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lempert, D. 1998. The Jewish question in Russia and the rewriting of history. Legal Studies Forum 22(3):457–472.

Lempert, D. 2000. Interpreting Vietnam: ideology and "newspeak." Legal Studies Forum 24(1):175.

Lempert, D. 2010. Why we need a cultural red book for endangered cultures, NOW. International Journal of Minority and Group Rights 17(4):511–550.

Lempert, D. & Nguyen, H. 2008. A sustainable development indicator for NGOs and international organizations. International Journal of Sustainable Society 1(1):44–54. Reprinted in Mother Pelican,

August 2011.

Lempert, D. & Nguyen, H. 2009. A convenient truth about global warming: why most of the major powers really want global warming. The Ecologist 39(1):86. Reprinted in Mother Pelican,

September 2011.

Mol, A. 1995. The Refinement of Production: Ecological Modernization Theory and the Chemical Industry. Utrecht: Jan van Arkel/International Books.

Morgenstern, O. & von Neumann, J. 1947. The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Nash, J. 1951. Non-cooperative games. The Annals of Mathematics 54(2):286–295.

Nguyen, H. 2008. Toxic Omissions and Cancerous Growths: Addressing the Unexamined Assumption of Sustainable Consumption in Technologically Innovative Societies. Unpublished Masters Thesis. The International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics. Lund University, Sweden.

Prosperity Initiative. 2008. History: Oxfam Prosperity Initiative. January 14, 2008.

Prebisch, R. 1950. Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems. New York: United Nations Department of Economic Affairs.

Sahlins, M. 1960. Evolution and Culture. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Sampson, A. 1975. The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Shaped. New York: Vintage Press.

Shellenberger, M. & Nordhaus, T. 2004. The Death of Environmentalism: Global Warming Politics in a Post-Environmental World. Oakland, CA: The Breakthrough Institute.

Solow, R. 1993. Sustainability: an economist's perspective. In R. Dorfman & N. Dorfman (Eds.), Economics of the Environment: Selected Readings, pp. 179–187. New York: W.W. Norton.

Speth, J. 2008. The Bridge at the Edge of the World: Capitalism, the Environment, and Crossing from Crisis to Sustainability. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Stern, D. 2003. The environmental Kuznets curve. Online Encyclopedia of Ecological Economics.

Steward, J. 1955. Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. 2010. Policy for Economic Growth in Swedish Development Cooperation, 2010–2014. Appendix to Government Decision UF/2010/6949/UP. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet.

Tainter, J. 1990. The Collapse of Complex Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

United Nations. 1948. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, January 12, 1951. 78 United Nations Treaty Series 277.

United Nations. 1966. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and Optional Protocol, March 23, 1976. 999 United Nations Treaty Series 171.

United Nations. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child, September 2, 1990. 1577 United Nations Treaty Series 3.

United Nations. 1999. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, 3-14 June 1992. March 30, 2011.

United Nations. 2000a. Statement by James Gustave Speth, Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme, World Summit for Social Development, Copenhagen, Denmark. 6 March 1995. March 30, 2011.

United Nations. 2000b. United Nations Millennium Declaration. GA 55/2, September 8. March 30, 2011.

United Nations. 2007. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. GA Resolution 61/295, September 13. March 30, 2011.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2008. Initiative on Legal Empowerment of the Poor. March 30, 2011.

United Nations Development Programme & United Nations Population Fund (UNDP & UNFP). 2007. UNDP Strategic Plan, 2008–2011: Accelerating Global Progress on Human Development, DP/2007/43. New York: United Nations.

Wallerstein, I. 1974. The Modern World System, Volume. I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic Press.

Wilson, E. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, E. 1998. Concilience. New York: Alfred Knopf.

World Bank. 1992. World Development Report. New York: Oxford University Press.

York, R., Rosa, E., & Dietz, T. 2005. The ecological footprint intensity of national economies. Journal of Industrial Ecology 8(4):139–154.