Introduction

The purpose of this research has been to better understand how to address our biggest

social, environmental, and economic challenges. The specific area I have studied is how leaders and

change agents with a complex meaning-making system design and engage with sustainability

initiatives. By identifying how such leaders respond to sustainability challenges, future and existing

leaders can be taught to be more effective.

If humanity is going to achieve important global objectives like the United Nations’

Millennium Development Goals and mitigating our impact upon the climate, we will need to change.

Research and experience suggest that some of our change efforts toward this more sustainable world

will work, while many will not (Kotter, 1995). Amongst the myriad success drivers for a change

initiative, a key component is the design of the initiative itself (Doppelt, 2010; Kotter, 1996). In turn,

one of the most important influences on the design of change initiatives is the worldview of the

designer(s) (Doppelt, 2010; Sharma, 2000). It is this leverage point – the worldview or meaning-

making system of the designer of sustainability initiatives – that I have studied. Leaders with a more

complex meaning-making system have access to enhanced and new capacities that others do not.

This strengthens their ability to respond to sophisticated challenges (Kegan, 1994; Rooke & Torbert,

1998; Strang & Kuhnert, 2009; Torbert, et al., 2004). By better understanding how these individuals

respond to sustainability issues, we can foster the development of more of such leaders.

Little is known about the impact of a leader’s worldview on the architecture and development

of sustainability initiatives. While the adult development literature (Kegan, 1994; Torbert, et al.,

2004) offers some insights, there has been no empirical research in this area until this study. In

general, there is very little robust research on the intersection of sustainability and leadership (Cox,

2005; van Velsor, 2009). While there is a consistent call for strong and courageous leadership to

drive the sustainability agenda (A. P. Kakabadse & Kakabadse, 2007; Senge, 2008), few studies

describe what such leadership looks like in action. This study helps fill parts of that gap, specifically

those relating to the design and engagement of sustainability initiatives.

Methodology

I used a variation of the Washington University Sentence Completion Test

(Loevinger & Wessler, 1970) to assess the meaning-making capacity, or action logic, of 32 leaders

and change agents from business, government, and civil society who are engaged in sustainability

work. From this sample, I identified 13 who measured at the three latest stages assessed by this

instrument. I interviewed them about their experience and process regarding the design and

engagement of sustainability initiatives. Through thematic analysis of the interview data, and

building upon insights from my literature review, I then compiled a set of propositions and findings

about this topic.

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework that has guided my inquiry is composed

of two theoretical lenses: constructive-developmental theory and sustainability leadership theory.

Constructive-developmental theory (Cook-Greuter, 1999, 2004; Kegan, 1982, 1994; Loevinger,

1976; Torbert, 2003; Torbert, et al., 2004), a branch of psychology, is a stage theory of adult

development. Research indicates that there is a range of worldviews, meaning-making structures, or

action logics through which adults have the potential to grow. Roughly, each of the stages of

development involves the reorganization of meaning-making, perspective, self-identity, and the

overall way of knowing. I have used the lens of constructive-developmental theory to identify and

differentiate the meaning-making structures amongst the research participants. Additionally, this

theory informs my framing of how change agents design and engage with sustainability initiatives.

The findings of constructive-developmental theory ground my belief that holding a late-stage action

logic, all other factors being equal, may grant a significant advantage to change agents who design

sustainability initiatives. Later action logics offer a broader vision and deeper understanding of the

territory (Cook-Greuter, 2004; Torbert, et al., 2004). Similar to scaling a mountain, the higher one

climbs, the further one can see.

My second theoretical lens is sustainability leadership theory. This field goes by many

different names, depending on the perspective it addresses. These titles include corporate social

responsibility (CSR) leadership, environmental leadership, and ethical leadership. The most relevant

dimensions of this literature for my study are those that identify the values and worldviews (Boiral,

Cayer, & Baron, 2009; Shrivastava, 1994), competencies (Hind, Wilson, & Lenssen, 2009; N. K.

Kakabadse, Kakabadse, & Lee-Davies, 2009), and the behaviors (Doppelt, 2010; Quinn & Dalton,

2009) that sustainability leaders need. Most of this research is exploratory, and, until this study, none

of it has measured the influence of developmental maturity on sustainability leadership. Nonetheless,

some studies (Boiral, et al., 2009; Doppelt, 2010; Hames, 2007; Hardman, 2009) strongly support the

need for leaders that have a sophisticated worldview and have begun to document what such a

perspective looks like in practice. I have used this literature to gain insight into how leaders with a

late-stage action logic might design sustainability initiatives.

Summary of Findings

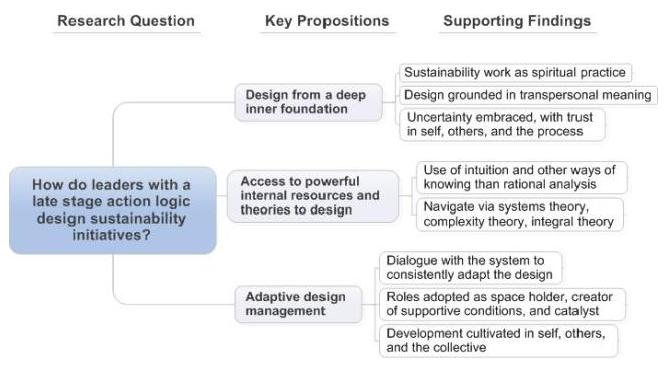

There are three major propositions I make based upon the findings of

this study. They are: (1) These leaders design from a deep inner foundation; (2) they access powerful

internal resources and theories to distill and evolve the design; and (3) they adaptively manage the

design. These propositions, respectively, relate to three different aspects of change agency: Being,

Reflecting, and Engaging. "Being" refers to fundamental or essential qualities of these individuals;

that is, it has to do with characteristics of who they are. "Reflecting" concerns how they think about

and gain insight into the design. "Engaging" addresses the actions they take to develop and manage

the design. Each of the three propositions are supported by two or three major findings, and all are

summarized in the figure below.

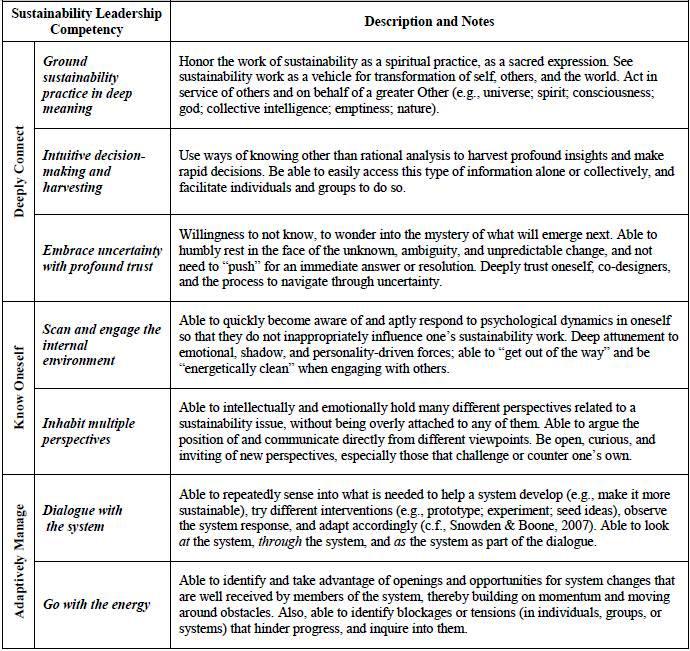

I have consolidated further details about these findings into two tables below. The first

concerns sustainability leadership competencies, and the second relates to the role and approach of

sustainability leaders with a late-stage action logic.

|

Note on the Concept of Action Logics

"The term action logic describes the developmental stage of meaning-making that informs and drives an individual’s reasoning and behavior. Torbert created this phrase to describe the stages of ego development in a way that was more aligned with the language of organizations and leadership. The action logics framework utilized by Torbert and Cook-Greuter (Cook-Greuter, 1999; Torbert, et al., 2004), based upon Loevinger’s original ego development framework (Loevinger, 1966), offers a nine-stage model. Table 2 provides a brief overview of the eight most prevalent action logics. (The complete model has an earlier action logic most reflective of a child’s center of gravity). As individuals advance through the stages, they organize their experiences according to an increasingly complex logic (e.g., needs, system effectiveness, most valuable principles)."

Barret C. Brown's Ph.D. Dissertation, page 34.

|

If more complex meaning-making systems are correlated with greater leadership

effectiveness (Eigel & Kuhnert, 2005; Fisher & Torbert, 1991; Harris & Kuhnert, 2006, 2008;

McCauley, Drath, Palus, O'Connor, & Baker, 2006; Rooke & Torbert, 1998; Strang & Kuhnert,

2009), then sustainability leadership development should focus on building the meaning-making

capacity (i.e., action logic) of leaders and change agents. An important implication of this study for

sustainability leadership theory is that the existing suite of leadership competencies identified in the

literature may be insufficient for addressing many sustainability challenges. New leadership

competencies are likely needed to help cultivate leaders who can handle complex global issues.

Based upon the results of this study, I propose 15 competencies (see Table 1). These are likely

appropriate for change agents and sustainability leaders who hold a late-stage action logic.

Development of these competencies may help facilitate their growth into the later action logics of the

Strategist and Alchemist, and therefore unlock the capacities offered by those ways of making

meaning. This should not be considered a definitive list, but rather a first step toward a competency

model for sustainability leaders with a late-stage action logic.

Table 1

15 competencies that may support development of sustainability leaders with a late action logic

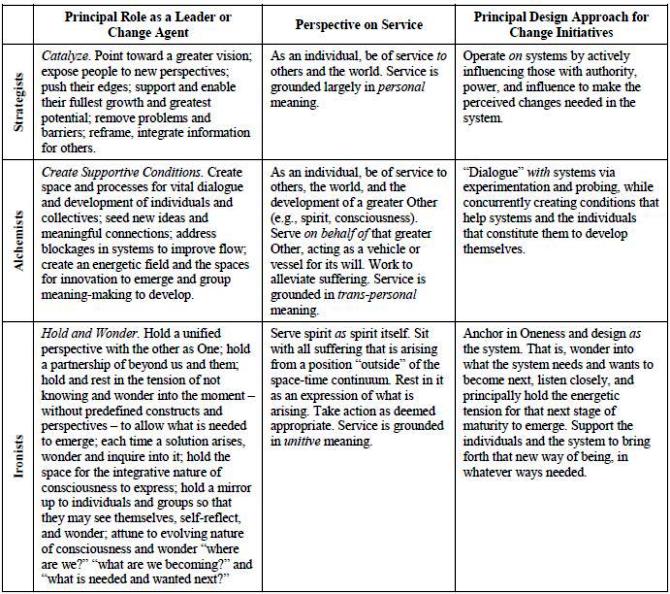

This study also revealed, for the first time, empirically identified variations in how

individuals with late action logics perceive and act in three important dimensions. These are: (1) the

principal role they take as a change agent; (2) their perspective on service; and (3) the general

approach they use when designing change initiatives. None of these dimensions have been

articulated in the constructive-developmental literature or sustainability leadership literature before.

These findings are synthesized in Table 2.

Table 2

Comparison of role, service, and design approach of research sample participants

Conclusion

In my opinion, the widespread development of leadership consciousness is

integral to global sustainability. This work is a vital piece of the puzzle, as postconventional

meaning-making offers significant advantages and abilities over earlier worldviews. With this

research, I have attempted to accomplish two things. First, I wanted to strengthen the linkage

between the fields of leadership development for sustainability and constructive-developmentalism.

Secondly, I wanted to empirically identify specific actions and capacities of leaders with a late-stage

action logic. These, in turn, can be used to help guide the development of leaders and change agents

into the postconventional realm, thereby aiding them to unlock greater potential. I believe that I have

made strong advances in both of these areas.

From a scholarly perspective, I recognize that the propositions, competencies, and practices

postulated in this study are hypothetical and subject to validation and refinement. I invite other

researchers to do this work and therefore drive our collective understanding of developmentally

mature leadership. However, from a practitioner standpoint, I believe that now is the time to act. We

have enough evidence to make bold strides forward regarding the design of leadership development

programs for change agents globally. I have looked closely at the existing research, studied peers

who are sustainability leaders, and personally served as a sustainability leader using many of the

competencies and practices discussed here. From this empirical and experiential research I can state

unequivocally that there are considerable leadership advantages to holding a late stage meaning-

making system. We should, therefore, shift our attention to embedding practices that foster

developmental maturity into leadership development programs whenever possible.

References

Beck, Don E., & Cowan, Christopher C. (1996). Spiral Dynamics: Mastering values, leadership and change.

Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Bertalanffy, Ludwig von (1968). General systems theory. New York: Braziller.

Boiral, Olivier, Cayer, Mario, & Baron, Charles M. (2009). The action logics of environmental leadership: A

developmental perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 479-499.

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (1999). Postautonomous ego development: A study of its nature and measurement.

Dissertation Abstracts International, 60 06B(UMI No. 993312),

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2004). Making the case for a developmental perspective. Industrial and Commercial

Training, 36(6/7), 275.

Cox, C. K. (2005). Organic leadership: The co-creation of good business, global prosperity, and a greener

future. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Benedictine University.

Doppelt, Bob (2010). Leading change toward sustainability: A change-management guide for business,

government and civil society (2nd ed.). Sheffield: Greenleaf.

Edwards, Mark G. (2009). Organizational transformation for sustainability: An integral metatheory. London:

Routledge.

Eigel, K. M., & Kuhnert, K. W. (2005). Authentic development: leadership development level and executive

effectiveness. In W. Gardner, B. Avolio & F. Walumba (Eds.), Authentic leadership theory and

practice: Origins, effects and development. Monographs in Leadership and Management (Vol. 3, pp.

357-385). Oxford: Elsevier.

Fisher, D., & Torbert, W. R. (1991). Transforming managerial practice: Beyond the achiever stage. In R.

Woodman & W. Pasmore (Eds.), Research in Organizational Change and Development (Vol. 5, pp.

143-173).

Hames, Richard David (2007). The five literacies of global leadership: What authentic leaders know and you

need to find out. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Hardman, G. (2009). Regenerative leadership: An integral theory for transforming people and organizations

for sustainability in business, education, and community. Unpublished Ph.D., Florida Atlantic

University, United States -- Florida.

Harris, L. S., & Kuhnert, K. W. (2006). An examination of executive leadership effectiveness using

constructive/developmental theory. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of

Management, Atlanta, GA.

Harris, L. S., & Kuhnert, K. W. (2008). Looking through the lens of leadership: A constructive developmental

approach. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29(1), 47-67.

Hind, P., Wilson, A., & Lenssen, G. (2009). Developing leaders for sustainable business. Corporate

Governance, 9(1), 7.

Johnson, Barry (1992). Polarity management: Identifying and managing unsolvable problems. Amherst, MA:

HRD Press.

Johnson, Barry (1993). Polarity management. Executive Development, 6(2), 28.

Kakabadse, A. P., & Kakabadse, N. K. (2007). CSR in practice: Delving deep. Basingstoke [England]; New

York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kakabadse, N. K., Kakabadse, A. P., & Lee-Davies, L. (2009). CSR leaders road-map. Corporate

Governance, 9(1), 50.

Kauffman, S. A. (1995). At home in the universe: The search for laws of self-organization and complexity.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Kegan, Robert (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Kegan, Robert (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Kotter, John P. (1995). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, 73(2), 59.

Kotter, John P. (1996). Leading change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Laszlo, Ervin (1972). Introduction to systems philosophy: Toward a new paradigm of contemporary thought.

New York: Gordon and Breach.

Loevinger, J. (1966). The meaning and measurement of ego-development. American Psychologist, 21, 195-

206.

Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego development: conceptions and theories. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Loevinger, J., & Wessler, R. (1970). Measuring ego development: Vol. 1. Construction and use of a sentence

completion test. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Marion, R., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2001). Leadership in complex organizations. The Leadership Quarterly, 12(4),

389.

McCauley, C. D., Drath, W. H., Palus, C. J., O'Connor, P. M. G., & Baker, B. A. (2006). The use of

constructive-developmental theory to advance the understanding of leadership. The Leadership

Quarterly, 17(6), 634.

Quinn, Laura, & Dalton, Maxine (2009). Leading for sustainability: Implementing the tasks of leadership.

Corporate Governance, 9(1), 21-38.

Rooke, D., & Torbert, W. R. (1998). Organizational transformation as a function of CEO's developmental

stage. Organization Development Journal, 16(1), 11-28.

Senge, Peter M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York:

Doubleday/Currency.

Senge, Peter M. (2008). The necessary revolution: How individuals and organizations are working together to

create a sustainable world. New York: Doubleday.

Sharma, Sanjay (2000). Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate

choice of environmental strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 681.

Shrivastava, Paul (1994). Ecocentric leadership in the 21st century. The Leadership Quarterly, 5(3), 223-226.

Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A leader's framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review

(November).

Stacey, R. D. (1996). Complexity and creativity in organizations. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Strang, S., & Kuhnert, K. W. (2009). Personality and Leadership Developmental Levels as predictors of

leader performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 421.

Torbert, W. R. (1987). Managing the corporate dream: Restructuring for long-term success. Homewood, IL:

Dow Jones-Irwin.

Torbert, W. R. (2000). A developmental approach to social science: Integrating first-, second-, and third-

person research/practice through single-, double-, and triple-loop feedback. Journal of Adult

Development, 7(4), 255-268.

Torbert, W. R. (2003). Personal and organizational transformations through action inquiry. London: The

Cromwell Press.

Torbert, W. R., Cook-Greuter, S. R., Fisher, D., Foldy, E., Gauthier, A., Keeley, J., et al. (2004). Action

inquiry: The secret of timely and transformational leadership. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Uhl-Bien, M., & Marion, R. (Eds.). (2008). Complexity leadership, Part 1: Conceptual foundations. Charlotte,

NC: Information Age Publishing.

van Velsor, E. (2009). Introduction: Leadership and corporate social responsibility. Corporate Governance,

9(1), 3-6.

Wilber, Ken (1995). Sex, ecology, spirituality: The spirit of evolution. Boston: Shambhala.

Wilber, Ken (2000). A theory of everything: An integral vision for business, politics, science, and spirituality.

Boston: Shambhala.

Wilber, Ken, Patten, Terry, Leonard, Adam, & Morelli, Marco (2008). Integral life practice: A 21st century

blueprint for physical health, emotional balance, mental clarity and spiritual awakening. Boston:

Integral Books.

About the Author: Since 1995, Barrett C. Brown has worked in nine countries as a consultant and entrepreneur in the areas of leadership, organization development, communications, and sustainability. He has helped launch a dozen organizations, led executive teams through strategic alignment, developed multi-year leadership development programs, delivered leadership initiatives for Fortune 500 executives, and briefed high-level officials at the United Nations Development Programme headquarters and the US State Department. He specializes in the intersection between organization development, leadership development, and global sustainability.

|