For those concerned with the fate of the earth, the time has come to

face facts: not simply the dire reality of climate change but also the

pressing need for social-system change. The failure to arrive at a world

climate agreement in Copenhagen in December 2009 was not simply an

abdication of world leadership, as is often suggested, but had deeper

roots in the inability of the capitalist system to address the

accelerating threat to life on the planet. Knowledge of the nature and

limits of capitalism, and the means of transcending it, has therefore

become a matter of survival. In the words of Fidel Castro in December

2009: “Until very recently, the discussion [on the future of world

society] revolved around the kind of society we would have. Today, the

discussion centers on whether human society will survive.”1

I. The Planetary Ecological Crisis

There is abundant evidence that humans have caused environmental

damage for millennia. Problems with deforestation, soil erosion, and

salinization of irrigated soils go back to antiquity. Plato wrote in Critias:

What proof then can we offer that it [the land

in the vicinity of Athens] is…now a mere remnant of what it once

was?…You are left (as with little islands) with something rather like

the skeleton of a body wasted by disease; the rich, soft soil has all

run away leaving the land nothing but skin and bone. But in those days

the damage had not taken place, the hills had high crests, the rocky

plane of Phelleus was covered with rich soil, and the mountains were

covered by thick woods, of which there are some traces today. For some

mountains which today will only support bees produced not so long ago

trees which when cut provided roof beams for huge buildings whose roofs

are still standing. And there were a lot of tall cultivated trees which

bore unlimited quantities of fodder for beasts. The soil benefitted from

an annual rainfall which did not run to waste off the bare earth as it

does today, but was absorbed in large quantities and stored in retentive

layers of clay, so that what was drunk down by the higher regions

flowed downwards into the valleys and appeared everywhere in a multitude

of rivers and springs. And the shrines which still survive at these

former springs are proof of the truth of our present account of the

country.2

What is different in our current era is that there are many more of

us inhabiting more of the earth, we have technologies that can do much

greater damage and do it more quickly, and we have an economic system

that knows no bounds. The damage being done is so widespread that it not

only degrades local and regional ecologies, but also affects the

planetary environment.

There are many sound reasons that we, along with many other people,

are concerned about the current rapid degradation of the earth’s

environment. Global warming, brought about by human-induced increases in

greenhouse gases (CO2, methane, N2O, etc.), is in the process of

destabilizing the world’s climate—with horrendous effects for most

species on the planet and humanity itself now increasingly probable.

Each decade is warmer than the one before, with 2009 tying as the second

warmest year (2005 was the warmest) in the 130 years of global

instrumental temperature records.3 Climate

change does not occur in a gradual, linear way, but is non-linear, with

all sorts of amplifying feedbacks and tipping points. There are already

clear indications of accelerating problems that lie ahead. These

include:

- Melting of the Arctic Ocean ice during the

summer, which reduces the reflection of sunlight as white ice is

replaced by dark ocean, thereby enhancing global warming. Satellites

show that end-of-summer Arctic sea ice was 40 percent less in 2007 than

in the late 1970s when accurate measurements began.4

- Eventual disintegration of the Greenland

and Antarctic ice sheets, set in motion by global warming, resulting in a

rise in ocean levels. Even a sea level rise of 1-2 meters would be

disastrous for hundreds of millions of people in low-lying countries

such as Bangladesh and Vietnam and various island states. A sea level

rise at a rate of a few meters per century is not unusual in the

paleoclimatic record, and therefore has to be considered possible, given

existing global warming trends. At present, more than 400 million

people live within five meters above sea level, and more than one

billion within twenty-five meters.5

- The rapid decrease of the world’s mountain

glaciers, many of which—if business-as-usual greenhouse gas emissions

continue—could be largely gone (or gone altogether) during this century.

Studies have shown that 90 percent of mountain glaciers worldwide are

already visibly retreating as the planet warms. The Himalayan glaciers

provide dry season water to countries with billions of people in Asia.

Their shrinking will lead to floods and acute water scarcity. Already

the melting of the Andean glaciers is contributing to floods in that

region. But the most immediate, current, and long-term problem,

associated with disappearing glaciers—visible today in Bolivia and

Peru—is that of water shortages.6

- Devastating droughts, expanding possibly to

70 percent of the land area within several decades under business as

usual; already becoming evident in northern India, northeast Africa, and

Australia.7

- Higher levels of CO2 in the atmosphere may

increase the production of some types of crops, but they may then be

harmed in future years by a destabilized climate that brings either dry

or very wet conditions. Losses in rice yields have already been measured

in parts of Southeast Asia, attributed to higher night temperatures

that cause the plant to undergo enhanced nighttime respiration. This

means losing more of what it produced by photosynthesis during the day.8

- Extinction of species due to changes in

climate zones that are too rapid for species to move or adapt to,

leading to the collapse of whole ecosystems dependent on these species,

and the death of still more species. (See below for more details on

species extinctions.)9

- Related to global warming, ocean

acidification from increased carbon absorption is threatening the

collapse of marine ecosystems. Recent indications suggest that ocean

acidification may, in turn, reduce the carbon-absorption efficiency of

the ocean. This means a potentially faster build-up of carbon dioxide in

the atmosphere, accelerating global warming.10

While global climate change and its consequences, along with its

“evil twin” of ocean acidification (also brought on by carbon

emissions), present by far the greatest threats to the earth’s species,

including humans, there are also other severe environmental issues.

These include contamination of the air and surface waters with

industrial pollutants. Some of these pollutants (the metal mercury, for

example) go up smoke stacks to later fall and contaminate soil and

water, while others are leached into surface waters from waste storage

facilities. Many ocean and fresh water fish are contaminated with

mercury as well as numerous industrial organic chemicals. The oceans

contain large “islands” of trash—“Light bulbs, bottle caps,

toothbrushes, Popsicle sticks and tiny pieces of plastic, each the size

of a grain of rice, inhabit the Pacific garbage patch, an area of widely

dispersed trash that doubles in size every decade and is now believed

to be roughly twice the size of Texas.”11

In the United States, drinking water used by millions of people is

polluted with pesticides such as atrazine as well as nitrates and other

contaminants of industrial agriculture. Tropical forests, the areas of

the greatest terrestrial biodiversity, are being destroyed at a rapid

pace. Land is being converted into oil palm plantations in Southeast

Asia—with the oil to be exported as a feedstock for making biodiesel

fuel. In South America, rainforests are commonly first converted to

extensive pastures and later into use for export crops such as soybeans.

This deforestation is causing an estimated 25 percent of all

human-induced release of CO2.12 Soil

degradation by erosion, overgrazing, and lack of organic material return

threatens the productivity of large areas of the world’s agricultural

lands.

We are all contaminated by a variety of chemicals. A recent survey of

twenty physicians and nurses tested for sixty-two chemicals in blood

and urine—mostly organic chemicals such as flame retardants and

plasticizers—found that

each participant had at least 24 individual

chemicals in their body, and two participants had a high of 39 chemicals

detected.…All participants had bisphenol A [used to make rigid

polycarbonate plastics used in water cooler bottles, baby bottles,

linings of most metal food containers—and present in the foods inside

these containers, kitchen appliances etc.], and some form of phthalates

[found in many consumer products such as hair sprays, cosmetics, plastic

products, and wood finishers], PBDEs [Polybrominated diphenyl ethers

used as flame retardants in computers, furniture, mattresses, and

medical equipment] and PFCs [Perfluorinated compounds used in non-stick

pans, protective coatings for carpets, paper coatings, etc.].13

Although physicians and nurses are routinely exposed to larger

quantities of chemicals than the general public, we are all exposed to

these and other chemicals that don’t belong in our bodies, and that most

likely have negative effects on human health. Of the 84,000 chemicals

in commercial use in the United States, we don’t even have an idea about

the composition and potential harmfulness of 20 percent (close to

20,000)—their composition falls under the category of “trade secrets”

and is legally withheld.14

Species are disappearing at an accelerated rate as their habitats are

destroyed, due not only to global warming but also to direct human

impact on species habitats. A recent survey estimated that over 17,000

animals and plants are at risk of extinction. “More than one in five of

all known mammals, over a quarter of reptiles and 70 percent of plants

are under threat, according to the survey, which featured over 2,800 new

species compared with 2008. ‘These results are just the tip of the

iceberg,’ said Craig Hilton-Taylor, who manages the list. He said many

more species that have yet to be assessed could also be under serious

threat.”15 As species disappear, ecosystems

that depend on the multitude of species to function begin to degrade.

One of the many consequences of degraded ecosystems with fewer species

appears to be greater transmission of infectious diseases.16

It is beyond debate that the ecology of the earth—and the very life

support systems on which humans as well as other species depend—is under

sustained and severe attack by human activities. It is also clear that

the effects of continuing down the same path will be devastating. As

James Hansen, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies,

and the world’s most famous climatologist, has stated: “Planet Earth,

creation, the world in which civilization developed, the world with

climate patterns that we know and stable shorelines, is in imminent

peril….The startling conclusion is that continued exploitation of all

fossil fuels on Earth threatens not only the other millions of species

on the planet but also the survival of humanity itself—and the timetable

is shorter than we thought.”17 Moreover,

the problem does not begin and end with fossil fuels but extends to the

entire human-economic interaction with the environment.

One of the latest, most important, developments in ecological

science is the concept of “planetary boundaries,” in which nine critical

boundaries/thresholds of the earth system have been designated in

relation to: (1) climate change; (2) ocean acidification; (3)

stratospheric ozone depletion; (4) the biogeochemical flow boundary (the

nitrogen cycle and the phosphorus cycles); (5) global freshwater use;

(6) change in land use; (7) biodiversity loss; (8) atmospheric aerosol

loading; and (9) chemical pollution. Each of these is considered

essential to maintaining the relatively benign climate and environmental

conditions that have existed during the last twelve thousand years (the

Holocene epoch). The sustainable boundaries in three of these

systems—climate change, biodiversity, and human interference with the

nitrogen cycle—may have already been crossed.18

II. Common Ground: Transcending Business as Usual

We strongly agree with many environmentalists who have concluded that

continuing “business as usual” is the path to global disaster. Many

people have determined that, in order to limit the ecological footprint

of human beings on the earth, we need to have an economy—particularly in

the rich countries—that doesn’t grow, so as to be able to stop and

possibly reverse the increase in pollutants released, as well as to

conserve non-renewable resources and more rationally use renewable

resources. Some environmentalists are concerned that, if world output

keeps expanding and everyone in developing countries seeks to attain the

standard of living of the wealthy capitalist states, not only will

pollution continue to increase beyond what the earth system can absorb,

but we will also run out of the limited non-renewable resources on the

globe. The Limits to Growth by Donella Meadows, Jorgen Randers, Dennis Meadows, and William Behrens, published in 1972 and updated in 2004 as Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update, is an example of concern with this issue.19

It is clear that there are biospheric limits, and that the planet

cannot support the close to 7 billion people already alive (nor, of

course, the 9 billion projected for mid-century) at what is known as a

Western, “middle class” standard of living. The Worldwatch Institute has

recently estimated that a world which used biocapacity per capita at

the level of the contemporary United States could only support 1.4

billion people.20 The primary problem is an

ancient one and lies not with those who do not have enough for a decent

standard of living, but rather with those for whom enough does not

exist. As Epicurus said: “Nothing is enough to someone for whom enough

is little.”21 A global social system

organized on the basis of “enough is little” is bound eventually to

destroy all around it and itself as well.

Many people are aware of the need for social justice when solving

this problem, especially because so many of the poor are living under

dangerously precarious conditions, have been especially hard hit by

environmental disaster and degradation, and promise to be the main

victims if current trends are allowed to continue. It is clear that

approximately half of humanity—over three billion people, living in deep

poverty and subsisting on less than $2.50 a day—need to have access to

the requirements for a basic human existence such as decent housing, a

secure food supply, clean water, and medical care. We wholeheartedly

agree with all of these concerns.22

Some environmentalists feel that it is possible to solve most of our

problems by tinkering with our economic system, introducing greater

energy efficiency and substituting “green” energy sources for fossil

fuels—or coming up with technologies to ameliorate the problems (such as

using carbon capture from power plants and injecting it deep into the

earth). There is a movement toward “green” practices to use as marketing

tools or to keep up with other companies claiming to use such

practices. Nevertheless, within the environmental movement, there are

some for whom it is clear that mere technical adjustments in the current

productive system will not be enough to solve the dramatic and

potentially catastrophic problems we face.

Curtis White begins his 2009 article in Orion, entitled “The

Barbaric Heart: Capitalism and the Crisis of Nature,” with: “There is a

fundamental question that environmentalists are not very good at

asking, let alone answering: ‘Why is this, the destruction of the

natural world, happening?’”23 It is impossible to find real and lasting solutions until we are able satisfactorily to answer this seemingly simple question.

It is our contention that most of the critical environmental problems

we have are either caused, or made much worse, by the workings of our

economic system. Even such issues as population growth and technology

are best viewed in terms of their relation to the socioeconomic

organization of society. Environmental problems are not a result of

human ignorance or innate greed. They do not arise because managers of

individual large corporations or developers are morally deficient.

Instead, we must look to the fundamental workings of the economic (and

political/social) system for explanations. It is precisely the fact that

ecological destruction is built into the inner nature and logic of our

present system of production that makes it so difficult to solve.

In addition, we shall argue that “solutions” proposed for

environmental devastation, which would allow the current system of

production and distribution to proceed unabated, are not real solutions.

In fact, such “solutions” will make things worse because they give the

false impression that the problems are on their way to being overcome

when the reality is quite different. The overwhelming environmental

problems facing the world and its people will not be effectively dealt

with until we institute another way for humans to interact with

nature—altering the way we make decisions on what and how much to

produce. Our most necessary, most rational goals require that we take

into account fulfilling basic human needs, and creating just and

sustainable conditions on behalf of present and future generations

(which also means being concerned about the preservation of other

species).

III. Characteristics of Capitalism in Conflict with the Environment

The economic system that dominates nearly all corners of the world is

capitalism, which, for most humans, is as “invisible” as the air we

breathe. We are, in fact, largely oblivious to this worldwide system,

much as fish are oblivious to the water in which they swim. It is

capitalism’s ethic, outlook, and frame of mind that we assimilate and

acculturate to as we grow up. Unconsciously, we learn that greed,

exploitation of laborers, and competition (among people, businesses,

countries) are not only acceptable but are actually good for society

because they help to make our economy function “efficiently.”

Let’s consider some of the key aspects of capitalism’s conflict with environmental sustainability.

A. Capitalism Is a System that Must Continually Expand

No-growth capitalism is an oxymoron: when growth ceases, the system

is in a state of crisis with considerable suffering among the

unemployed. Capitalism’s basic driving force and its whole reason for

existence is the amassing of profits and wealth through the accumulation

(savings and investment) process. It recognizes no limits to its own

self-expansion—not in the economy as a whole; not in the profits desired

by the wealthy; and not in the increasing consumption that people are

cajoled into desiring in order to generate greater profits for

corporations. The environment exists, not as a place with inherent

boundaries within which human beings must live together with earth’s

other species, but as a realm to be exploited in a process of growing

economic expansion.

Indeed, businesses, according to the inner logic of capital, which is

enforced by competition, must either grow or die—as must the system

itself. There is little that can be done to increase profits from

production when there is slow or no growth. Under such circumstances,

there is little reason to invest in new capacity, thus closing off the

profits to be derived from new investment. There is also just so much

increased profit that can be easily squeezed out of workers in a

stagnant economy. Such measures as decreasing the number of workers and

asking those remaining to “do more with less,” shifting the costs of

pensions and health insurance to workers, and introducing automation

that reduces the number of needed workers can only go so far without

further destabilizing the system. If a corporation is large enough it

can, like Wal-Mart, force suppliers, afraid of losing the business, to

decrease their prices. But these means are not enough to satisfy what

is, in fact, an insatiable quest for more profits, so corporations are

continually engaged in struggle with their competitors (including

frequently buying them out) to increase market share and gross sales.

It is true that the system can continue to move forward, to some

extent, as a result of financial speculation leveraged by growing debt,

even in the face of a tendency to slow growth in the underlying economy.

But this means, as we have seen again and again, the growth of

financial bubbles that inevitably burst.24

There is no alternative under capitalism to the endless expansion of the

“real economy” (i.e., production), irrespective of actual human needs,

consumption, or the environment.

One might still imagine that it would be theoretically possible

for a capitalist economy to have zero growth, and still meet all of

humanity’s basic needs. Let’s suppose that all the profits that

corporations earn (after allowing for replacing worn out equipment or

buildings) are either spent by capitalists on their own consumption or

given to workers as wages and benefits, and consumed. As capitalists and

workers spend this money, they would purchase the goods and services

produced, and the economy could stay at a steady state, no-growth level

(what Marx called “simple reproduction” and has sometimes been called

the “stationary state”). Since there would be no investment in new

productive capacity, there would be no economic growth and accumulation,

no profits generated.

There is, however, one slight problem with this “capitalist no-growth

utopia”: it violates the basic motive force of capitalism. What capital

strives for and is the purpose of its existence is its own expansion.

Why would capitalists, who in every fiber of their beings believe that

they have a personal right to business profits, and who are driven to

accumulate wealth, simply spend the economic surplus at their disposal

on their own consumption or (less likely still) give it to workers to

spend on theirs—rather than seek to expand wealth? If profits are not

generated, how could economic crises be avoided under capitalism? To the

contrary, it is clear that owners of capital will, as long as such

ownership relations remain, do whatever they can within their power to

maximize the amount of profits they accrue. A stationary state, or

steady-state, economy as a stable solution is only conceivable if

separated from the social relations of capital itself.

Capitalism is a system that constantly generates a reserve army of

the unemployed; meaningful, full employment is a rarity that occurs only

at very high rates of growth (which are correspondingly dangerous to

ecological sustainability). Taking the U.S. economy as the example,

let’s take a look at what happens to the number of “officially”

unemployed when the economy grows at different rates during a period of

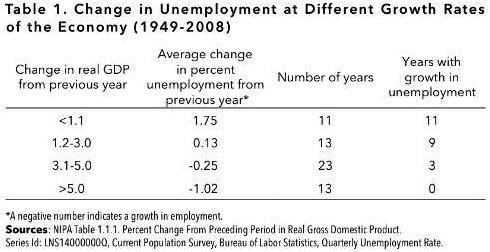

close to sixty years (Table 1).

For background, we should note that the U.S. population is

growing by a little less than 1 percent a year, as is the net number of

new entrants into the normal working age portion of the population. In

current U.S. unemployment measurements, those considered to be

officially unemployed must have looked for work within the last four

weeks and cannot be employed in part-time jobs. Individuals without

jobs, who have not looked for work during the previous four weeks (but

who have looked within the last year), either because they believe there

are no jobs available, or because they think there are none for which

they are qualified, are classified as “discouraged” and are not counted

as officially unemployed. Other “marginally attached workers,” who have

not recently looked for work (but have in the last year), not because

they were “discouraged,” but for other reasons, such as lack of

affordable day care, are also excluded from the official unemployment

count. In addition, those working part-time but wanting to work

full-time are not considered to be officially unemployed. The

unemployment rate for the more expanded definition of unemployment (U-6)

provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which also includes the

above categories (i.e., discouraged workers, other marginally attached

workers, and part-time workers desiring full-time employment) is

generally almost twice the official U.S. employment rate (U-3). In the

following analysis, we focus only on the official unemployment data.

What, then, do we see in the relationship between economic growth and unemployment over the last six decades?

- During the eleven years of very slow growth, less than 1.1 percent per year, unemployment increased in each of the years.

- In 70 percent (nine of thirteen) of the years when GDP grew between 1.2 and 3 percent per year, unemployment also grew.

- During the twenty-three years when the U.S.

economy grew fairly rapidly (from 3.1 to 5.0 percent a year),

unemployment still increased in three years and reduction in the percent

unemployed was anemic in most of the others.

- Only in the thirteen years when the GDP

grew at greater than 5.0 percent annually did unemployment not increase

in any of these years.

Although this table is based on calendar years and does not follow

business cycles, which, of course, do not correspond neatly to the

calendar, it is clear that, if the GDP growth rate isn’t substantially

greater than the increase in population, people lose jobs. While slow or

no growth is a problem for business owners trying to increase their

profits, it is a disaster for working people.

What this tells us is that the capitalist system is a very crude

instrument in terms of providing jobs in relation to growth—if growth is

to be justified by employment. It will take a rate of growth of around 4

percent or higher, far above the average growth rate, before the

unemployment problem is surmounted in U.S. capitalism today. Worth

noting is the fact that, since the 1940s, such high rates of growth in

the U.S. economy have hardly ever been reached except in times of wars.

B. Expansion Leads to Investing Abroad in Search of Secure Sources of Raw Materials, Cheaper Labor, and New Markets

As companies expand, they saturate, or come close to saturating, the

“home” market and look for new markets abroad to sell their goods. In

addition, they and their governments (working on behalf of corporate

interests) help to secure entry and control over key natural resources

such as oil and a variety of minerals. We are in the midst of a

“land-grab,” as private capital and government sovereign wealth funds

strive to gain control of vast acreage throughout the world to produce

food and biofuel feedstock crops for their “home” markets. It is

estimated that some thirty million hectares of land (roughly equal to

two-thirds of the arable land in Europe), much of them in Africa, have

been recently acquired or are in the process of being acquired by rich

countries and international corporations.25

This global land seizure (even if by “legal” means) can be regarded

as part of the larger history of imperialism. The story of centuries of

European plunder and expansion is well documented. The current U.S.-led

wars in Iraq and Afghanistan follow the same general historical pattern,

and are clearly related to U.S. attempts to control the main world

sources of oil and gas.26

Today multinational (or transnational) corporations scour the world

for resources and opportunities wherever they can find them, exploiting

cheap labor in poor countries and reinforcing, rather than reducing,

imperialist divisions. The result is a more rapacious global

exploitation of nature and increased differentials of wealth and power.

Such corporations have no loyalty to anything but their own bottom

lines.

C. A System that, by Its Very Nature, Must Grow and Expand Will

Eventually Come Up Against the Reality of Finite Natural Resources

The irreversible exhaustion of finite natural resources will leave

future generations without the possibility of having use of these

resources. Natural resources are used in the process of production—oil,

gas, and coal (fuel), water (in industry and agriculture), trees (for

lumber and paper), a variety of mineral deposits (such as iron ore,

copper, and bauxite), and so on. Some resources, such as forests and

fisheries, are of a finite size, but can be renewed by natural processes

if used in a planned system that is flexible enough to change as

conditions warrant. Future use of other resources—oil and gas, minerals,

aquifers in some desert or dryland areas (prehistorically deposited

water)—are limited forever to the supply that currently exists. The

water, air, and soil of the biosphere can continue to function well for

the living creatures on the planet only if pollution doesn’t exceed

their limited capacity to assimilate and render the pollutants harmless.

Business owners and managers generally consider the short term in

their operations—most take into account the coming three to five years,

or, in some rare instances, up to ten years. This is the way they must

function because of unpredictable business conditions (phases of the

business cycle, competition from other corporations, prices of needed

inputs, etc.) and demands from speculators looking for short-term

returns. They therefore act in ways that are largely oblivious of the

natural limits to their activities—as if there is an unlimited supply of

natural resources for exploitation. Even if the reality of limitation

enters their consciousness, it merely speeds up the exploitation of a

given resource, which is extracted as rapidly as possible, with capital

then moving on to new areas of resource exploitation. When each

individual capitalist pursues the goal of making a profit and

accumulating capital, decisions are made that collectively harm society

as a whole.

The length of time before nonrenewable deposits are exhausted depends

on the size of the deposit and the rate of extraction of the resource.

While depletion of some resources may be hundreds of years away

(assuming that the rate of growth of extraction remains the same),

limits for some important ones—oil and some minerals—are not that far

off. For example, while predictions regarding peak oil vary among energy

analysts—going by the conservative estimates of oil companies

themselves, at the rate at which oil is currently being used, known

reserves will be exhausted within the next fifty years. The prospect of

peak oil is projected in numerous corporate, government, and scientific

reports. The question today is not whether peak oil is likely to arrive

soon, but simply how soon.27

Even if usage doesn’t grow, the known deposits of the critical

fertilizer ingredient phosphorus that can be exploited on the basis of

current technology will be exhausted in this century.28

Faced with limited natural resources, there is no rational way to

prioritize under a modern capitalist system, in which the well-to-do

with their economic leverage decide via the market how commodities are

allocated. When extraction begins to decline, as is projected for oil

within the near future, price increases will put even more pressure on

what had been, until recently, the boast of world capitalism: the

supposedly prosperous “middle-class” workers of the countries of the

center.

The well-documented decline of many ocean fish species, almost to the

point of extinction, is an example of how renewable resources can be

exhausted. It is in the short-term individual interests of the owners of

fishing boats—some of which operate at factory scale, catching,

processing, and freezing fish—to maximize the take. Hence, the fish are

depleted. No one protects the common interest. In a system run generally

on private self-interest and accumulation, the state is normally

incapable of doing so. This is sometimes called the tragedy of the

commons. But it should be called the tragedy of the private exploitation

of the commons.

The situation would be very different if communities that have a

stake in the continued availability of a resource managed the resource

in place of the large-scale corporation. Corporations are subject to the

single-minded goal of maximizing short-term profits—after which they

move on, leaving devastation behind, in effect mining the earth.

Although there is no natural limit to human greed, there are limits, as

we are daily learning, to many resources, including “renewable” ones,

such as the productivity of the seas. (The depletion of fish off the

coast of Somalia because of overfishing by factory-scale fishing fleets

is believed to be one of the causes for the rise of piracy that now

plagues international shipping in the area. Interestingly, the

neighboring Kenyan fishing industry is currently rebounding because the

pirates also serve to keep large fishing fleets out of the area.)

The exploitation of renewable resources before they can be renewed is

referred to as “overshooting” the resource. This is occurring not only

with the major fisheries, but also with groundwater (for example, the

Oglala aquifer in the United States, large areas of northwestern India,

Northern China, and a number of locations in North Africa and the Middle

East), with tropical forests, and even with soils.

Duke University ecologist John Terborgh described a recent trip he

took to a small African nation where foreign economic exploitation is

combined with a ruthless depletion of resources.

Everywhere I went, foreign commercial

interests were exploiting resources after signing contracts with the

autocratic government. Prodigious logs, four and five feet in diameter,

were coming out of the virgin forest, oil and natural gas were being

exported from the coastal region, offshore fishing rights had been sold

to foreign interests, and exploration for oil and minerals was underway

in the interior. The exploitation of resources in North America during

the five-hundred-year post-discovery era followed a typical

sequence—fish, furs, game, timber, farming virgin soils—but because of

the hugely expanded scale of today’s economy and the availability of

myriad sophisticated technologies, exploitation of all the resources in

poor developing countries now goes on at the same time. In a few years,

the resources of this African country and others like it will be sucked

dry. And what then? The people there are currently enjoying an illusion

of prosperity, but it is only an illusion, for they are not preparing

themselves for anything else. And neither are we.29

D. A System Geared to Exponential Growth in the Search for Profits Will Inevitably Transgress Planetary Boundaries

The earth system can be seen as consisting of a number of critical

biogeochemical processes that, for hundreds of millions of years, have

served to reproduce life. In the last 12 thousand or so years the world

climate has taken the relatively benign form associated with the

geological epoch known as the Holocene, during which civilization arose.

Now, however, the socioeconomic system of capitalism has grown to such a

scale that it overshoots fundamental planetary boundaries—the carbon

cycle, the nitrogen cycle, the soil, the forests, the oceans. More and

more of the terrestrial (land-based) photosynthetic product, upwards of

40 percent, is now directly accounted for by human production. All

ecosystems on earth are in visible decline. With the increasing scale of

the world economy, the human-generated rifts in the earth’s metabolism

inevitably become more severe and more multifarious. Yet, the demand for

more and greater economic growth and accumulation, even in the

wealthier countries, is built into the capitalist system. As a result,

the world economy is one massive bubble.

There is nothing in the nature of the current system, moreover, that

will allow it to pull back before it is too late. To do that, other

forces from the bottom of society will be required.

E. Capitalism Is Not Just an Economic System—It Fashions a

Political, Judicial, and Social System to Support the System of Wealth

and Accumulation

Under capitalism people are at the service of the economy and are

viewed as needing to consume more and more to keep the economy

functioning. The massive and, in the words of Joseph Schumpeter,

“elaborate psychotechnics of advertising” are absolutely necessary to

keep people buying.30 Morally, the system

is based on the proposition that each, following his/her own interests

(greed), will promote the general interest and growth. Adam Smith

famously put it: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the

brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to

their own interest.”31 In other words,

individual greed (or quest for profits) drives the system and human

needs are satisfied as a mere by-product. Economist Duncan Foley has

called this proposition and the economic and social irrationalities it

generates “Adam’s Fallacy.”32

The attitudes and mores needed for the smooth functioning of such

a system, as well as for people to thrive as members of society—greed,

individualism, competitiveness, exploitation of others, and

“consumerism” (the drive to purchase more and more stuff, unrelated to

needs and even to happiness)—are inculcated into people by schools, the

media, and the workplace. The title of Benjamin Barber’s book—Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults, and Swallow Citizens Whole—says a lot.

The notion of responsibility to others and to community, which is the

foundation of ethics, erodes under such a system. In the words of

Gordon Gekko—the fictional corporate takeover artist in Oliver Stone’s

film Wall Street—“Greed is Good.” Today, in the face of

widespread public outrage, with financial capital walking off with big

bonuses derived from government bailouts, capitalists have turned to

preaching self-interest as the bedrock of society from the very pulpits.

On November 4, 2009, Barclay’s Plc Chief Executive Officer John Varley

declared from a wooden lectern in St. Martin-in-the-Fields at London’s

Trafalgar Square that “Profit is not Satanic.” Weeks earlier, on October

20, 2009, Goldman Sachs International adviser Brian Griffiths declared

before the congregation at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London that “The

injunction of Jesus to love others as ourselves is a recognition of

self-interest.”33

Wealthy people come to believe that they deserve their wealth because

of hard work (theirs or their forbearers) and possibly luck. The ways

in which their wealth and prosperity arose out of the social labor of

innumerable other people are downplayed. They see the poor—and the poor

frequently agree—as having something wrong with them, such as laziness

or not getting a sufficient education. The structural obstacles that

prevent most people from significantly bettering their conditions are

also downplayed. This view of each individual as a separate economic

entity concerned primarily with one’s (and one’s family’s) own

well-being, obscures our common humanity and needs. People are not

inherently selfish but are encouraged to become so in response to the

pressures and characteristics of the system. After all, if each person

doesn’t look out for “Number One” in a dog-eat-dog system, who will?

Traits fostered by capitalism are commonly viewed as being innate

“human nature,” thus making a society organized along other goals than

the profit motive unthinkable. But humans are clearly capable of a wide

range of characteristics, extending from great cruelty to great

sacrifice for a cause, to caring for non-related others, to true

altruism. The “killer instinct” that we supposedly inherited from

evolutionary ancestors—the “evidence” being chimpanzees’ killing the

babies of other chimps—is being questioned by reference to the peaceful

characteristics of other hominids such as gorillas and bonobos (as

closely related to humans as chimpanzees).34

Studies of human babies have also shown that, while selfishness is a

human trait, so are cooperation, empathy, altruism, and helpfulness.35

Regardless of what traits we may have inherited from our hominid

ancestors, research on pre-capitalist societies indicates that very

different norms from those in capitalist societies are encouraged and

expressed. As Karl Polanyi summarized the studies: “The outstanding

discovery of recent historical and anthropological research is that

man’s economy, as a rule, is submerged in his social relationships. He

does not act so as to safeguard his individual interest in the

possession of material goods; he acts so as to safeguard his social

standing, his social claims, his social assets.”36

In his 1937 article on “Human Nature” for the Encyclopedia of the

Social Sciences, John Dewey concluded—in terms that have been verified

by all subsequent social science—that:

The present controversies between those who

assert the essential fixity of human nature and those who believe in a

greater measure of modifiability center chiefly around the future of war

and the future of a competitive economic system motivated by private

profit. It is justifiable to say without dogmatism that both

anthropology and history give support to those who wish to change these

institutions. It is demonstrable that many of the obstacles to change

which have been attributed to human nature are in fact due to the

inertia of institutions and to the voluntary desire of powerful classes

to maintain the existing status.37

Capitalism is unique among social systems in its active, extreme

cultivation of individual self-interest or “possessive-individualism.”38

Yet the reality is that non-capitalist human societies have thrived

over a long period—for more than 99 percent of the time since the

emergence of anatomically modern humans—while encouraging other traits

such as sharing and responsibility to the group. There is no reason to

doubt that this can happen again.39

The incestuous connection that exists today between business

interests, politics, and law is reasonably apparent to most observers.40

These include outright bribery, to the more subtle sorts of buying

access, friendship, and influence through campaign contributions and

lobbying efforts. In addition, a culture develops among political

leaders based on the precept that what is good for capitalist business

is good for the country. Hence, political leaders increasingly see

themselves as political entrepreneurs, or the counterparts of economic

entrepreneurs, and regularly convince themselves that what they do for

corporations to obtain the funds that will help them get reelected is

actually in the public interest. Within the legal system, the interests

of capitalists and their businesses are given almost every benefit.

Given the power exercised by business interests over the economy,

state, and media, it is extremely difficult to effect fundamental

changes that they oppose. It therefore makes it next to impossible to

have a rational and ecologically sound energy policy, health care

system, agricultural and food system, industrial policy, trade policy,

education, etc.

IV. Characteristics of Capitalism in Conflict with Social Justice

The characteristics of capitalism discussed above—the necessity to

grow; the pushing of people to purchase more and more; expansion abroad;

use of resources without concern for future generations; the crossing

of planetary boundaries; and the predominant role often exercised by the

economic system over the moral, legal, political, cultural forms of

society—are probably the characteristics of capitalism that are most

harmful for the environment. But there are other characteristics of the system that greatly impact the issue of social justice. It is important to look more closely at these social contradictions imbedded in the system.

A. As the System Naturally Functions, a Great Disparity Arises in Both Wealth and Income

There is a logical connection between capitalism’s successes and its

failures. The poverty and misery of a large mass of the world’s people

is not an accident, some inadvertent byproduct of the system, one that

can be eliminated with a little tinkering here or there. The fabulous

accumulation of wealth—as a direct consequence of the way capitalism

works nationally and internationally—has simultaneously produced

persistent hunger, malnutrition, health problems, lack of water, lack of

sanitation, and general misery for a large portion of the people of the

world. The wealthy few resort to the mythology that the grand

disparities are actually necessary. For example, as Brian Griffiths, the

advisor to Goldman Sachs International, quoted above, put it: “We have

to tolerate the inequality as a way to achieving greater prosperity and

opportunity for all.”41 What’s good for the

rich also—according to them—coincidentally happens to be what’s good

for society as a whole, even though many remain mired in a perpetual

state of poverty.

Most people need to work in order to earn wages to purchase the

necessities of life. But, due to the way the system functions, there is a

large number of people precariously connected to jobs, existing on the

bottom rungs of the ladder. They are hired during times of growth and

fired as growth slows or as their labor is no longer needed for other

reasons—Marx referred to this group as the “reserve army of labor.”42

Given a system with booms and busts, and one in which profits are the

highest priority, it is not merely convenient to have a group of people

in the reserve army; it is absolutely essential to the smooth workings

of the system. It serves, above all, to hold down wages. The system,

without significant intervention by government (through large

inheritance taxes and substantial progressive income taxes), produces a

huge inequality of both income and wealth that passes from generation to

generation. The production of great wealth and, at the same time great

poverty, within and between countries is not coincidental—wealth and

poverty are likely two sides of the same coin.

In 2007, the top 1 percent of wealth holders in the United States

controlled 33.8 percent of the wealth of the country, while the bottom

50 percent of the population owned a mere 2.5 percent. Indeed, the

richest 400 individuals had a combined net worth of $1.54 trillion in 2007—approaching that of the bottom 150 million people

(with an aggregate net worth of $1.6 trillion). On a global scale, the

wealth of the world’s 793 billionaires is, at present, more than $3

trillion—equivalent to about 5 percent of total world income ($60.3

trillion in 2008). A mere 9 million people worldwide (around one-tenth

of 1 percent of world population) designated as “high net worth

individuals” currently hold a combined $35 trillion in wealth—equivalent

to more than 50 percent of world income.43

As wealth becomes more concentrated, the wealthy gain more political

power, and they will do what they can to hold on to all the money they

can—at the expense of those in lower economic strata. Most of the

productive forces of society, such as factories, machinery, raw

materials, and land, are controlled by a relatively small percentage of

the population. And, of course, most people see nothing wrong with this

seemingly natural order of things.

B. Goods and Services Are Rationed According to Ability to Pay

The poor do not have access to good homes or adequate food supplies

because they do not have “effective” demand—although they certainly have

biologically based demands. All goods are commodities. People without

sufficient effective demand (money) have no right in the capitalist

system to any particular type of commodity—whether it is a luxury such

as a diamond bracelet or a huge McMansion, or whether it is a necessity

of life such as a healthy physical environment, reliable food supplies,

or quality medical care. Access to all commodities is determined, not by

desire or need, but by having sufficient money or credit to purchase

them. Thus, a system that, by its very workings produces inequality and

holds back workers’ wages, ensures that many (in some societies, most)

will not have access to even the basic necessities or to what we might

consider a decent human existence.

It should be noted that, during periods when workers’ unions and

political parties were strong, some of the advanced capitalist countries

of Europe instituted a more generous safety net of programs, such as

universal health care, than those in the United States. This occurred as

a result of a struggle by people who demanded that the government

provide what the market cannot—equal access to some of life’s basic

needs.

C. Capitalism Is a System Marked by Recurrent Economic Downturns

In the ordinary business cycle, factories and whole industries

produce more and more during a boom—assuming it will never end and not

wanting to miss out on the “good times”—resulting in overproduction and

overcapacity, leading to a recession. In other words, the system is

prone to crises, during which the poor and near poor suffer the most.

Recessions occur with some regularity, while depressions are much less

frequent. Right now, we are in a deep recession or mini-depression (with

10 percent official unemployment), and many think we’ve averted a

full-scale depression by the skin of our teeth. All told, since the

mid-1850s there have been thirty-two recessions or depressions in the

United States (not including the current one)—with the average

contraction since 1945 lasting around ten months and the average

expansion between contractions lasting about six years.44

Ironically, from the ecological point of view, major

recessions—although causing great harm to many people—are actually a

benefit, as lower production leads to less pollution of the atmosphere,

water, and land.

V. Proposals for the Ecological Reformation of Capitalism

There are some people who fully understand the ecological and social

problems that capitalism brings, but think that capitalism can and

should be reformed. According to Benjamin Barber: “The struggle for the

soul of capitalism is…a struggle between the nation’s economic body and

its civic soul: a struggle to put capitalism in its proper place, where

it serves our nature and needs rather than manipulating and fabricating

whims and wants. Saving capitalism means bringing it into harmony with

spirit—with prudence, pluralism and those ‘things of the public’…that

define our civic souls. A revolution of the spirit.”45

William Greider has written a book titled The Soul of Capitalism:

Opening Paths to a Moral Economy. And there are books that tout the

potential of “green capitalism” and the “natural capitalism” of Paul

Hawken, Amory Lovins, and L. Hunter Lovins.46

Here, we are told that we can get rich, continue growing the economy,

and increase consumption without end—and save the planet, all at the

same time! How good can it get? There is a slight problem—a system that

has only one goal, the maximization of profits, has no soul, can never

have a soul, can never be green, and, by its very nature, it must

manipulate and fabricate whims and wants.

There are a number of important “out of the box” ecological and

environmental thinkers and doers. They are genuinely good and

well-meaning people who are concerned with the health of the planet, and

most are also concerned with issues of social justice. However, there

is one box from which they cannot escape—the capitalist economic system.

Even the increasing numbers of individuals who criticize the system and

its “market failures” frequently end up with “solutions” aimed at a

tightly controlled “humane” and non-corporate capitalism, instead of

actually getting outside the box of capitalism. They are unable even to

think about, let alone promote, an economic system that has different

goals and decision-making processes—one that places primary emphasis on

human and environmental needs, as opposed to profits.

Corporations are outdoing each other to portray themselves as

“green.” You can buy and wear your Gucci clothes with a clean conscience

because the company is helping to protect rainforests by using less

paper.47 Newsweek claims that corporate

giants such as Dell, Hewlett-Packard, Johnson & Johnson, Intel, and

IBM are the top five green companies of 2009 because of their use of

“renewable” sources of energy, reporting greenhouse gas emissions (or

lowering them), and implementing formal environmental policies and good

reputations.48 You can travel wherever you

want, guilt-free, by purchasing carbon “offsets” that supposedly cancel

out the environmental effects of your trip.

Let’s take a look at some of the proposed devices for dealing with the ecological havoc without disturbing capitalism.

A. Better Technologies that Are More Energy Efficient and Use Fewer Material Inputs

Some proposals to enhance energy efficiency—such as those to help

people tighten up their old homes so that less fuel is required to heat

in the winter—are just plain common sense. The efficiency of machinery,

including household appliances and automobiles, has been going up

continually, and is a normal part of the system. Although much more can

be accomplished in this area, increased efficiency usually leads to

lower costs and increased use (and often increased size as well, as in

automobiles), so that the energy used is actually increased. The

misguided push to “green” agrofuels has been enormously detrimental to

the environment. Not only has it put food and auto fuel in direct

competition, at the expense of the former, but it has also sometimes

actually decreased overall energy efficiency.49

B. Nuclear Power

Some scientists concerned with climate change, including James

Lovelock and James Hansen, see nuclear power as an energy alternative,

and as a partial technological answer to the use of fossil fuels; one

that is much preferable to the growing use of coal. However, although

the technology of nuclear energy has improved somewhat, with

third-generation nuclear plants, and with the possibility (still not a

reality) of fourth-generation nuclear energy, the dangers of nuclear

power are still enormous—given radioactive waste lasting hundreds and

thousands of years, the social management of complex systems, and the

sheer level of risk involved. Moreover, nuclear plants take about ten

years to build and are extremely costly and uneconomic. There are all

sorts of reasons, therefore (not least of all, future generations), to

be extremely wary of nuclear power as any kind of solution. To go in

that direction would almost certainly be a Faustian bargain.50

C. Large-Scale Engineering Solutions

A number of vast engineering schemes have been proposed either to

take CO2 out of the atmosphere or to increase the reflectance of

sunlight back into space, away from earth. These include: Carbon sequestration schemes

such as capturing CO2 from power plants and injecting it deep into the

earth, and fertilizing the oceans with iron so as to stimulate algal

growth to absorb carbon; and enhanced sunlight reflection schemes

such as deploying huge white islands in the oceans, creating large

satellites to reflect incoming sunlight, and contaminating the

stratosphere with particles that reflect light.

No one knows, of course, what detrimental side effects might occur

from such schemes. For example, more carbon absorption by the oceans

could increase acidification, while dumping sulphur dioxide into the

stratosphere to block sunlight could reduce photosynthesis.

Also proposed are a number of low-tech ways to sequester carbon such

as increasing reforestation and using ecological soil management to

increase soil organic matter (which is composed mainly of carbon). Most

of these should be done for their own sake (organic material helps to

improve soils in many ways). Some could help to reduce the carbon

concentration in the atmosphere. Thus reforestation, by pulling carbon

from the atmosphere, is sometimes thought of as constituting negative

emissions. But low-tech solutions cannot solve the problem given an

expanding system—especially considering that trees planted now can be

cut down later, and carbon stored as soil organic matter may later be

converted to CO2 if practices are changed.

D. Cap and Trade (Market Trading) Schemes

The favorite economic device of the system is what are called

“cap and trade” schemes for limiting carbon emissions. This involves

placing a cap on the allowable level of greenhouse gas emissions and

then distributing (either by fee or by auction) permits that allow

industries to emit carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Those

corporations that have more permits than they need may sell them to

other firms wanting additional permits to pollute. Such schemes

invariably include “offsets” that act like medieval indulgences,

allowing corporations to continue to pollute while buying good grace by

helping to curtail pollution somewhere else—say, in the third world.

In theory, cap and trade is supposed to stimulate technological

innovation to increase carbon efficiency. In practice, it has not led to

carbon dioxide emission reductions in those areas where it has been

introduced, such as in Europe. The main result of carbon trading has

been enormous profits for some corporations and individuals, and the

creation of a subprime carbon market.51

There are no meaningful checks of the effectiveness of the “offsets,”

nor prohibitions for changing conditions sometime later that will result

in carbon dioxide release to the atmosphere.

VI. What Can Be Done Now?

In the absence of systemic change, there certainly are things that

have been done and more can be done in the future to lessen capitalism’s

negative effects on the environment and people. There is no particular

reason why the United States can’t have a better social welfare system,

including universal health care, as is the case in many other advanced

capitalist countries. Governments can pass laws and implement

regulations to curb the worst environmental problems. The same goes for

the environment or for building affordable houses. A carbon tax of the

kind proposed by James Hansen, in which 100 percent of the dividends go

back to the public, thereby encouraging conservation while placing the

burden on those with the largest carbon footprints and the most wealth,

could be instituted. New coal-fired plants (without sequestration) could

be blocked and existing ones closed down.52

At the world level, contraction and convergence in carbon emissions

could be promoted, moving to uniform world per capita emissions, with

cutbacks far deeper in the rich countries with large per capita carbon

footprints.53 The problem is that very

powerful forces are strongly opposed to these measures. Hence, such

reforms remain at best limited, allowed a marginal existence only

insofar as they do not interfere with the basic accumulation drive of

the system.

Indeed, the problem with all these approaches is that they allow the

economy to continue on the same disastrous course it is currently

following. We can go on consuming all we want (or as much as our income

and wealth allow), using up resources, driving greater distances in our

more fuel-efficient cars, consuming all sorts of new products made by

“green” corporations, and so on. All we need to do is support the new

“green” technologies (some of which, such as using agricultural crops to

make fuels, are actually not green!) and be “good” about separating out

waste that can be composted or reused in some form, and we can go on

living pretty much as before—in an economy of perpetual growth and

profits.

The very seriousness of the climate change problem arising from

human-generated carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions has

led to notions that it is merely necessary to reduce carbon footprints

(a difficult problem in itself). The reality, though, is that there are

numerous, interrelated, and growing ecological problems arising from a

system geared to the infinitely expanding accumulation of capital. What

needs to be reduced is not just carbon footprints, but ecological footprints,

which means that economic expansion on the world level and especially

in the rich countries needs to be reduced, even cease. At the same time,

many poor countries need to expand their economies. The new principles

that we could promote, therefore, are ones of sustainable human

development. This means enough for everyone and no more. Human

development would certainly not be hindered, and could even be

considerably enhanced for the benefit of all, by an emphasis on

sustainable human, rather than unsustainable economic, development.

VII. Another Economic System Is Not Just Possible—It’s Essential

The foregoing analysis, if correct, points to the fact that the

ecological crisis cannot be solved within the logic of the present

system. The various suggestions for doing so have no hope of success.

The system of world capitalism is clearly unsustainable in: (1) its

quest for never ending accumulation of capital leading to production

that must continually expand to provide profits; (2) its agriculture and

food system that pollutes the environment and still does not allow

universal access to a sufficient quantity and quality of food; (3) its

rampant destruction of the environment; (4) its continually recreating

and enhancing of the stratification of wealth within and between

countries; and (5) its search for technological magic bullets as a way

of avoiding the growing social and ecological problems arising from its

own operations.

The transition to an ecological—which we believe must also be a

socialist—economy will be a steep ascent and will not occur overnight.

This is not a question of “storming the Winter Palace.” Rather, it is a

dynamic, multifaceted struggle for a new cultural compact and a new

productive system. The struggle is ultimately against the system of capital. It must begin, however, by opposing the logic of capital,

endeavoring in the here and now to create in the interstices of the

system a new social metabolism rooted in egalitarianism, community, and a

sustainable relation to the earth. The basis for the creation of

sustainable human development must arise from within the system dominated by capital, without being part of it, just as the bourgeoisie itself arose in the “pores” of feudal society.54 Eventually, these initiatives can become powerful enough to constitute the basis of a revolutionary new movement and society.

All over the world, such struggles in the interstices of capitalist

society are now taking place, and are too numerous and too complex to be

dealt with fully here. Indigenous peoples today, given a new basis as a

result of the ongoing revolutionary struggle in Bolivia, are

reinforcing a new ethic of responsibility to the earth. La Vía

Campesina, a global peasant-farmer organization, is promoting new forms

of ecological agriculture, as is Brazil’s MST (Movimento dos

Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra), as are Cuba and Venezuela. Recently,

Venezulean President Hugo Chávez stressed the social and environmental

reasons to work to get rid of the oil-rentier model in Venezuela, a

major oil exporter.55 The climate justice

movement is demanding egalitarian and anti-capitalist solutions to the

climate crisis. Everywhere radical, essentially anti-capitalist,

strategies are emerging, based on other ethics and forms of

organization, rather than the profit motive: ecovillages; the new urban

environment promoted in Curitiba in Brazil and elsewhere; experiments in

permaculture, and community-supported agriculture, farming and

industrial cooperatives in Venezuela, etc. The World Social Forum has

given voice to many of these aspirations. As leading U.S.

environmentalist James Gustave Speth has stated: “The international

social movement for change—which refers to itself as ‘the irresistible

rise of global anti-capitalism’—is stronger than many may imagine and

will grow stronger.”56

The reason that the opposition to the logic of capitalism—ultimately

seeking to displace the system altogether—will grow more imposing is

that there is no alternative, if the earth as we know it, and humanity

itself, are to survive. Here, the aims of ecology and socialism will

necessarily meet. It will become increasingly clear that the

distribution of land as well as food, health care, housing, etc. should

be based on fulfilling human needs and not market forces. This is, of

course, easier said than done. But it means making economic decisions

through democratic processes occurring at local, regional, and

multiregional levels. We must face such issues as: (1) How can we supply

everyone with basic human needs of food, water, shelter, clothing,

health care, educational and cultural opportunities? (2) How much of the

economic production should be consumed and how much invested? and (3)

How should the investments be directed? In the process, people must find

the best ways to carry on these activities with positive interactions

with nature—to improve the ecosystem. New forms of democracy will be

needed, with emphasis on our responsibilities to each other, to one’s

own community as well as to communities around the world. Accomplishing

this will, of course, require social planning at every level: local,

regional, national, and international—which can only be successful to

the extent that it is of and by, and not just ostensibly for, the people.57

An economic system that is democratic, reasonably egalitarian, and

able to set limits on consumption will undoubtedly mean that people will

live at a significantly lower level of consumption than what is

sometimes referred to in the wealthy countries as a “middle class”

lifestyle (which has never been universalized even in these societies). A

simpler way of life, though “poorer” in gadgets and ultra-large luxury

homes, can be richer culturally and in reconnecting with other people

and nature, with people working the shorter hours needed to provide

life’s essentials. A large number of jobs in the wealthy capitalist

countries are nonproductive and can be eliminated, indicating that the

workweek can be considerably shortened in a more rationally organized

economy. The slogan, sometimes seen on bumper stickers, “Live Simply so

that Others May Simply Live,” has little meaning in a capitalist

society. Living a simple life, such as Helen and Scott Nearing did,

demonstrating that it is possible to live a rewarding and interesting

life while living simply, doesn’t help the poor under present

circumstances.58 However, the slogan will

have real importance in a society under social (rather than private)

control, trying to satisfy the basic needs for all people.

Perhaps the Community Councils of Venezuela—where local people decide

the priorities for social investment in their communities and receive

the resources to implement them—are an example of planning for human

needs at the local level. This is the way that such important needs as

schools, clinics, roads, electricity, and running water can be met. In a

truly transformed society, community councils can interact with

regional and multiregional efforts. And the use of the surplus of

society, after accounting for peoples’ central needs, must be based on

their decisions.59

The very purpose of the new sustainable system, which is the

necessary outcome of these innumerable struggles (necessary in terms of

survival and the fulfillment of human potential), must be to satisfy the

basic material and non-material needs of all the people, while

protecting the global environment as well as local and regional

ecosystems. The environment is not something “external” to the human

economy, as our present ideology tells us; it constitutes the essential

life support systems for all living creatures. To heal the “metabolic

rift” between the economy and the environment means new ways of living,

manufacturing, growing food, transportation and so forth.60

Such a society must be sustainable; and sustainability requires

substantive equality, rooted in an egalitarian mode of production and

consumption.

Concretely, people need to live closer to where they work, in

ecologically designed housing built for energy efficiency as well as

comfort, and in communities designed for public engagement, with

sufficient places, such as parks and community centers, for coming

together and recreation opportunities. Better mass transit within and

between cities is needed to lessen the dependence on the use of the cars

and trucks. Rail is significantly more energy efficient than trucks in

moving freight (413 miles per gallon fuel per ton versus 155 miles for

trucks) and causes fewer fatalities, while emitting lower amounts of

greenhouse gases. One train can carry the freight of between 280 to 500

trucks. And it is estimated that one rail line can carry the same amount

of people as numerous highway lanes.61

Industrial production needs to be based on ecological design principles

of “cradle-to-cradle,” where products and buildings are designed for

lower energy input, relying to as great degree as possible on natural

lighting and heating/cooling, ease of construction as well as easy

reuse, and ensuring that the manufacturing process produces little to no

waste.62

Agriculture based on ecological principles and carried out by family

farmers working on their own, or in cooperatives and with animals,

reunited with the land that grows their food has been demonstrated to be

not only as productive or more so than large-scale industrial

production, but also to have less negative impact on local ecologies. In

fact, the mosaic created by small farms interspersed with native

vegetation is needed to preserve endangered species.63

A better existence for slum dwellers, approximately one-sixth of

humanity, must be found. For the start, a system that requires a “planet

of slums,” as Mike Davis has put it, has to be replaced by a system

that has room for food, water, homes, and employment for all.64 For many, this may mean returning to farming, with adequate land and housing and other support provided.

Smaller cities may be needed, with people living closer to where

their food is produced and industry more dispersed, and smaller scale.

Evo Morales, President of Bolivia, has captured the essence of the

situation in his comments about changing from capitalism to a system

that promotes “living well” instead of “living better.” As he put it at

the Copenhagen Climate Conference in December 2009: “Living better is to

exploit human beings. It’s plundering natural resources. It’s egoism

and individualism. Therefore, in those promises of capitalism, there is

no solidarity or complementarity. There’s no reciprocity. So that’s why

we’re trying to think about other ways of living lives and living well,

not living better. Living better is always at someone else’s expense.

Living better is at the expense of destroying the environment.”65

The earlier experiences of transition to non-capitalist systems,

especially in Soviet-type societies, indicate that this will not be

easy, and that we need new conceptions of what constitutes socialism,

sharply distinguished from those early abortive attempts.

Twentieth-century revolutions typically arose in relatively poor,

underdeveloped countries, which were quickly isolated and continually

threatened from abroad. Such post-revolutionary societies usually ended

up being heavily bureaucratic, with a minority in charge of the state

effectively ruling over the remainder of the society. Many of the same

hierarchical relations of production that characterize capitalism were

reproduced. Workers remained proletarianized, while production was

expanded for the sake of production itself. Real social improvements all

too often existed side by side with extreme forms of social repression.66

Today we must strive to construct a genuine socialist system; one in

which bureaucracy is kept in check, and power over production and

politics truly resides with the people. Just as new challenges that

confront us are changing in our time, so are the possibilities for the

development of freedom and sustainability.

When Reverend Jeremiah Wright spoke to Monthly Review’s

sixtieth anniversary gathering in September 2009, he kept coming back to

the refrain “What about the people?” If there is to be any hope of

significantly improving the conditions of the vast number of the world’s

inhabitants—many of whom are living hopelessly under the most severe

conditions—while also preserving the earth as a livable planet, we need a

system that constantly asks: “What about the people?” instead of “How

much money can I make?” This is necessary, not only for humans, but for

all the other species that share the planet with us and whose fortunes

are intimately tied to ours.

Notes