|

Determining the Role of Adult Education

in the Process for Building

the Culture of Sustainable Development

Pauline A. McLean, Ph.D.

Department of Educational Leadership,

Florida Atlantic University,

Boca Raton, Florida, USA

This paper is based on the author's Ph.D. dissertation,

An assessment of the effect of adult education on sustainable development in Jamaica

30 April 2009

Abstract

An effect size of 4% was observed for this study that assessed the effect of adult education on sustainable development in Jamaica. The surveys had high internal reliability of 0.973 as measured by Cronbach’s alpha statistic. The inquiry was framed around social, economic and environmental interdependencies. The assessment was informed by correlation analysis and structured comparative descriptions of data representing six metrics, the knowledge and the behaviors related to environmental sustainability, economic sustainability and social responsibility. Facilitators and trainees concurred that the training programs did not motivate sustainable behaviors. Based on the results, implications for leadership commitment and accountability, good governance, and continuous learning were emphasized as critical elements of sustainability.

Introduction

Over the years, education has operated as a social and economic indicator, building human capacity to improve living standards and quality lifestyles. Education has given people the ability to make informed choices and has encouraged the questioning of prevailing governance systems and developmental patterns. In most cases, people who increase their knowledge and skills also improve their performances to contribute more to the development of stable societies. Several researchers (Center for Urban and Environmental Studies, 2007; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2000; Ekins & Medhurst, 2006; Fowler, 2004; Seelos & Mair, 2005; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 2002, 2007) have documented evidence of direct improvements between an educated workforce and the economic prosperity and stability of nations. Consequently, a key role exists for educators who can explore with learners their social responsibility for determining what sustainable development might be.

Since the launching of the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD) 2005-2014, the theme, think globally, act locally has become popular among educators (UNESCO, 2007). DESD has challenged people everywhere to make conscious efforts to reform and reconfigure ideas that match domestic needs and concerns. In addition, the effects of climate change are creating a sense of urgency for citizens of a nation to begin translating thoughts and ideas into local actions. As citizens and countries become concerned about greening jobs and economies, sustainable development (SD) is perceived as an unending process that has both global and local relevance. However, ministries of education across the globe have been in a quandary over how to begin creating and implementing programs that integrate elements of sustainability in curricula, because education for sustainable development (ESD) should “always be implemented in a locally relevant and culturally appropriate fashion” (Hopkins, 2003, p.1). According to the governments of the United Kingdom (UK), SD is about five shared principles: a) living within environmental limits; b) achieving a sustainable economy; c) ensuring a strong, healthy and just society; d) promoting good governance; and e) using sound science responsibly (UK Guiding Strategies, as cited in UK Government Sustainable Development, 2006). Given the conundrum that SD has created for educators, the United Nations Environmental Programme (2003, 2006) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2002, 2007) have made resources available for forging relationships among developed and developing nations. Consequently, nations will be able to work out concrete policy implications that are relevant to differing ecological conditions, and not overwhelm people with generic information that is not relevant to their context.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this paper is to present and discuss the findings of an assessment of adult education programs in Jamaica with the international community so that educators may be able to integrate the goals of sustainability across disciplines. The effect of the programs on economic sustainability, social responsibility and environmental sustainability was determined from two perspectives, content delivery and behavioral outcomes or application of the knowledge. The research was conducted primarily, to provide curriculum planners and instructional leadership with results that can influence the redesign, the development and the implementation of effective sustainability training courses. A secondary albeit esoteric purpose for this research is that it may become useful in shaping policies for fostering the mindset of citizens into building sustainable futures.

Limitations of the Study

The investigation is limited to a single developing nation, and one adult education facility. The Human Employment and Resource Training /National Training Agency (HEART/NTA) is the premier adult and continuing education agency in Jamaica. HEART/NTA provides vocational training for economic viability, or more specifically, for raising the standard of living of the Jamaican worker. The sample was randomly selected from four of several program offerings: a) agriculture, b) automotive trade services, c) construction and building services, and d) hospitality services. These programs were perceived to involve major SD concerns with their concomitant trade-offs between the society, the economy and the environment. Concerns for land use, energy and transport dependence, the safety and efficiency of buildings, and the travel and the tourism trade can be readily associated with these program deliverables.

The investigation was also limited by the availability of resources. The survey research method was selected instead of the case study method because it would have taken the single investigator/researcher several months or years to collect the same amount of data. The survey method offered a quick and efficient way to collect large volumes of data from widely dispersed groups within a few days. In addition, secondary sources were utilized to augment the identification of global concerns for the conduct of the investigation. Another unobtrusive limitation of the study is the overarching assumption that adult educators adopt transformational learning approaches. The evidence did support the discourse for the single line of inquiry, perspective transformation that was adopted by the researcher.

Theoretical Perspectives

The SD concept challenges conventional thinking and practices, and all core issues of decision-making. Gibson, Hassan, Holtz, Tansey and Whitelaw (2007) contended that sustainable development is not a state to be achieved, but rather a set of principles to apply and processes to follow. This contention is consistent with Mog’s (2004) argument that SD must “be seen as an unending process--defined not by fixed goals or the specific means of achieving them, but by an approach to creating change through continuous learning and adaptation” (p. 2139). Other proponents of SD consider that the principles and processes for achieving SD depend on new partnerships among governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), health and justice systems, educators and academia, businesses, telecommunications, scientific and local communities and the media. SD requires greater cooperation among stakeholder groups for reducing mitigation costs and for improving the effectiveness of implementation plans. The cooperation of everyone is needed for birthing the culture of sustainability that will allow poorer nations to benefit from the provision of clean and renewable energy sources as well as fresh, potable water (UNESCO, 2002).

History and Structure of Sustainable Development

Before 1987, awareness of the SD objective was low in both the developed and developing worlds. To define the linkage between the environment and development, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, first used the term sustainable development in a 1980 publication of the World Conservation Strategy. Seven years later, The Brundtland Commission adopted the terminology or concept to describe development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. (http://www.worldaware.org.uk/education/sustain.html, para.1) Nevertheless, the SD concept gained acceptance across regions following the dissemination of strategies that helped humans developed respect for five shared principles. The principles delineated by the UK Government (Welsh Assembly Government, 2006) are as follows:

- Living within environmental limits

- Achieving a sustainable economy

- Ensuring a strong, healthy and just society

- Promoting good governance

- Using sound science responsibly

Subsequently, other governments showed their commitment for the SD movement by greening budgets to allow development of policies and frameworks for balancing the economic, the environmental and the social landscapes. Operating under the umbrella of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), the United Nations (UN) made funds available for programs to support the integration of policies for achieving SD. The UN efforts were advanced by six developed nations, namely, Canada, Germany, France, the United States of America and the United Kingdom.

Developed and developing nations alike are now endorsing the objectives of SD for protecting and preserving the environment because they are convinced that economic and human development objectives are equally important to sustainability. Evidence of low levels of economic development influencing national integrity has been reported by several agencies and researchers (OECD, 2002; UNDP, 1997; UNESCO, 2002, 2007). These endorsements are consistent with the development needs and concerns outlined by the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement.

Notwithstanding, the WTO agreement present two major challenges for developing nations:

- A recognition that the different economic conditions of developing countries require special and differential (S&D) treatment, inclusive of sufficient policy space and flexibility with respect to WTO rules and obligations.

- Support in the achievement of their sustainable development objectives through the expansion of market access opportunities for their exports; the provision of adequate technical and financial assistance so that their trade-related economic development policies and activities reflect environmental sustainability considerations, including transfers of environmental goods and technologies (Yu and Fonseca-Marti, 2005).

The case for special and differential treatment is made on the basis that poor nations and regions of the world with limited financial resources experience much difficulty trying to maintain innovative treatment plants and sustainable technology with extremely high maintenance costs (ECLAC, 2000; Gafta & Ackeroyd, 2006; UNEP, 2002, 2003; UNESCO, 2002, 2007; Yu & Fonseca-Marti, 2005). Given their limitations, developing nations may be compelled to improve their economic conditions in the absence of environmental sustainability unless they can obtain exceptional technical and financial assistance from developed nations. Clearly, it will not be feasible to copy environmental standards from industrialized countries to developing countries because of the level of technical expertise required to ensure adequate performance of the technology. Unless financial aid or foreign loans are made available for paying the salaries of experts, it will not be possible to employ technical expertise from developed nations at the low wages paid by many developing nations. Subsequently, designs that work well in developed nations may not function well in developing nations.

Financial constraints and poor economic conditions open a window for proponents of SD to argue for cultural diversity or cultural sustainability as a critical element environmental sustainability. The presumption is that local communities may have to modify environmental standards set by the industrialized world to enable them to address the concerns of SD. Gafta and Ackeroyd (2006) suggested that a discontinued, environmentally friendly plant is considerably less sustainable than one that is less effective environmentally, but affordable and maintainable by the indigenous community.

In addition to the provision of adequate technical and financial assistance, it is necessary for poor nations to have inclusion and access to markets. Attaining world-class levels of sustainability is going to require more than minor adjustments to existing practices. Although education contributes to quality continuous improvement, lifelong learning or continuous education to help nations swell economies, quality education must be combined with good governance and leadership commitment for the reallocation of resources. Shifts in the capacity of individuals, corporations and countries for the use of resources with respect to current legal, environmental and economic arrangements are of import to building sustainable communities (Roseland, 2000; Welsh Assembly Government, 2006). Policy makers of underdeveloped and developing economies are of the opinion that they can construct the required facilities for operating more sustainable programs only if they have adequate funding and receive special and differential treatment.

Education for Sustainable Development

Over the years, civilized societies have skillfully utilized education to bring about changes in attitudes, behaviors and values. Education has encouraged full participation in community, national and global development and promoted voluntary efforts toward the conservation, the protection and the preservation of the environment. By increasing the knowledge and the skills of the populace, nations have progressively improved social and economic performances at both the individual and collective levels (CUES, 2004; ECLAC, 2002; ENACT, 2001; Fowler, 2004; UNDP, 1997; UNESCO, 2002). Subsequently, education for sustainable development (ESD) is providing a holistic approach to SD.

Since the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, ESD became the major driving force for SD. At this summit, it was agreed to promote ESD based upon four thrusts that were supposed to be implemented within three major policy areas, the environment, the society and the economy. The thrusts are as follows:

- Improving basic education

- Reorienting existing education to address sustainable development

- Developing public understanding, awareness

- Specialized training.

However, ministries of education across the globe have been in a quandary over how to begin creating and implementing programs (Hopkins, 2003; UNESCO, 2002, 2007) since ESD should “always be implemented in a locally relevant and culturally appropriate fashion” (Hopkins, p. 1). People everywhere need to be making conscious efforts to reform and to reconfigure ideas that match domestic needs and shape sustainable communities. Calder (2005) argued for people to start thinking: a) What are the key issues of ESD? b) How do they relate to me (or my organization) and c) What is my role in relation to them? These questions are important to the process because it is not necessary to overwhelm people with generic information that is not relevant to their context.

It is also important to observe the critical role that ESD plays in other ministries, such as, health, environment, energy and mining, planning, agriculture and commerce. UNESCO (2002) emphasized eight critical areas for educating people are: a) gender equality; b) health care; c) environmental stewardship; d) rural development; e) cultural diversity; f) peace and security; sustainable urbanization; and sustainable consumption. Adequate information needs to be combined with appropriate policy mechanisms to allow people to develop resource-limiting behaviors and build capacities for acting responsibly, as is evidenced by the unacceptability of smoking in public places.

Notwithstanding, ESD is presenting numerous challenges for policymakers and educators alike because it continues to be a complex, interdisciplinary theme that exists as environmental education, development education and education for citizenship. Retraining teachers to address ESD is a formidable task, even though teacher education institutions have the potential to bring about tremendous change (Hopkins, 2003; Zandvleit & Fisher, 2007). Nevertheless, before changes in curricula can occur, change must first occur among educators (Malhadas, 2003). As individuals, educators need to recognize the challenges that the SD concept poses. As a group, they need to collectively assume responsibility for capacity building and for fostering attitudinal changes among citizens. The challenge that modern educators face is: How can teachers teach about the notion of sustainability when educational theories and practices continually counter the objective of SD?

Adult Education Theories

Merriam and Caffarella (1999) contend that adult education is a large and amorphous field of practice with myriad content areas, delivery systems, goals and clienteles. Adult education is the glue that holds together a widely disparate field, ranging from adult basic education (ABE) to human resource development (HRD) and from educational gerontology to continuing professional education, argued Merriam (2004). These views explicitly build on the perspective transformation line of inquiry posited by Mezirow (as cited in Merriam & Caffarella, 1999). According to Merriam and Caffarella, Mezirow viewed transformative learning as a dramatic, fundamental change in the way adults see themselves and the world in which they live. Transformative learning focuses on the mental construction of experience, inner meaning, reframing and reflection for shaping people. As a consequence, adult education promotes transformative learning as a way to build capacity for thinking and for taking responsibility for one’s actions in the knowledge process. Thinking and acting responsibly foster the development of dispositions, such as self-determination and the recognition of challenges. These skills and attitudes, which are honed during the adult learning processes are critical to the concept of SD because they are likely to motivate useful action for changing behaviors.

While the role of education in capacity building and economic development cannot be ignored, adult education, unlike other types of educational development and learning, focuses on personal processes, application of knowledge or transfer of learning. Solutions discussed in class may be applied to a family or workplace situation the next day. Caffarella (2002) referred to such applications as transfer of learning. Merriam and Caffarella (1999) asserted that “the context of adult life and the societal context shape what an adult needs and wants to learn and, to a somewhat lesser extent when and where learning takes place.” (p. 1) Life experiences, experiential learning or deep knowledge that focus on immediate concerns are integral to adult learning. Deep knowledge fosters critical thinking and reflection. When learners are challenged to think about and reflect on issues that concern them, application of the knowledge usually follows the learning activity. But even though some good practices and individual ‘beacon’ projects exist in a piecemeal manner in the adult and continuing education (ACL) sector, no policies for directing progress on SD exist in ACL (Welsh Assembly Government, 2006).

Despite the launching of DESD 2005-2014, few adult learning programs exist for linking the health of people to the health and sustainability of ecosystems. Still, too few adult learners and community members are asked to reflect upon the impacts of their activities and those of their families and the wider society on the functioning of ecosystems (UNESCO, 2002). If governments and communities are going to find a way out of the conundrum, it will be necessary to define the role that adult education plays to help people understand the contextual implications of ESD.

Adult education, unlike other primary and secondary education, usually creates opportunities for transfer of learning. In the text, Planning Programs for Adult Learners, Caffarella (2002, p. 165) outlined eight distinct characteristics of adult learning:

- A clear relationship between the objectives and problems, ideas or needs.

- Focus on a critical skill sets, dispositions or content.

- Practical and doable objectives.

- Specific time-frame.

- Clear communication of proposed outcomes or accomplishments.

- Meaningful, tangible engagement that can be understood by all interested participants.

- Measurable objectives.

- Inclusion of prior knowledge, experiences and cababilities into learning activities.

Given the success that adult educators have had for changing behaviors and attitudes, it should not be difficult to redesign curricula and programs so that people are reoriented to act in ways that promote sustainability. Assuming that future generations will be able to benefit from such change, the following insights were gained from Chapter 36 of the UNESCO (2002) report on Education, Awareness and Learning, commonly called Agenda 21:36:

"Education, including formal education, public awareness and training should be recognized as a process by which human beings and societies can reach their fullest potential. Education is critical for achieving environmental and ethical awareness, values and attitudes, skills and behaviour consistent with sustainable development and for effective public participation in decision-making. Both formal and non-formal education are indispensable to changing people's attitudes so that they have the capacity to assess and address their sustainable development concerns." (pp. 6-7)

Adult Education in Jamaica

Jamaica has had a history of slavery and colonialism. Before emancipation in 1834, education was reserved for the white minority. During the post-emancipation era and the period leading to adult suffrage in 1938, adult education was reserved for the privileged and gifted. Tremendous increase in government services during the period 1939 to 1941 created opportunities for community educators to assist citizens in the utilization of the services provided by government to improve their economic conditions and personal circumstances (Manley, as cited in Riley, 2002). From the time that the Jamaica Welfare, a dominant community service provider, declared illiteracy as a social blindness and began to champion the case for increasing the literacy rate of the adult population, the adult education system in Jamaica has continually and consistently filled the gaps created by elementary, secondary, and tertiary education systems.

When welfare workers discovered that illiteracy hindered their mission for improving social conditions in the country, their focus shifted to the building of community through adult literacy. By the end of the 1940s, it became clear that the Jamaican education system was primarily responsible for the lack of achievement among the populace. In 1951, UNESCO responded to a request for assistance and provided personnel to develop reading materials while in 1954, The Jamaican Government provided funding to augment the literacy project (Riley, 2002). Initial radio experiments promoting literacy were so successful that when the country gained its independence from Britain in 1962, the masses embraced education for gaining social mobility and economic prosperity.

After almost two decades of informal educational programs for adult learning, The Jamaica Movement for the Advancement of Literacy (JAMAL) was established in November 1974. The launching of JAMAL represented a government initiative for reducing illiteracy among the adult population in the shortest time possible. When a 1970 UNESCO-sponsored survey assessed the illiteracy rate among Jamaican adults to be 40% to 50%, the national literacy campaign for the eradication of illiteracy gained momentum and much support from public officials. The government of 1972 was motivated to eradicate illiteracy in four years in its attempt to build a more equitable society. JAMAL reduced the illiteracy rate in the country considerably. Between 1972 and 1989, 248,000 adults became functionally literate. Marked reductions were noted for varying periods. In 1975, the rate was 32%. In 1981, illiteracy was reduced by 24.3%; in 1987, it was reduced by 18%; by 24.6% in 1994 and by 20.1% in 1999 (Riley, 2002).

Recently, an evaluation of educational outcomes identified a need for a new type of adult learning campaign. The target group was to be young adults or dropouts of the secondary education system. Remarkably, while the literacy rate among adults had consistently increased, the Jamaican secondary education system had been unable to produce sufficient numbers of graduates with the requisite competencies; creativity and flexibility for meeting the nation’s changing labor market needs (Riley, 2002; Jamaica. Task Force on Education Reform, 2004). Having surpassed expectations, JAMAL was renamed The Jamaica Foundation for Lifelong Learners (JFLL). Since its restructuring, JAMLL has partnered with other adult and continuing learning (ACL) facilities to provide enrichment programs for high school dropouts.

In January 2001, The Minister of Education, Youth and Culture (MOEYC) initiated a new relationship between JFLL and HEART/NTA for educating the secondary education system underachievers (Jamaica. Task Force on Education Reform, 2004). HEART/NTA was asked to develop the curriculum while JFLL was directed to plan, to pilot, to evaluate and to implement a delivery system for a High School Equivalency Program. This framework builds on an earlier plan to infuse the values related to sustainability in schools at both the elementary and secondary levels of the education system.

The National Environmental Education Action Plan

The National Environmental Education Action Plan for Sustainable Development (NEEAPSD) is a national framework for incorporating Environmental Education for Sustainable Development (EESD) into all aspects of Jamaican life. NEEAPSD communicated a vision of a sustainable future for Jamaica and presented specific goals and outcomes for achieving the vision. The vision embraced a framework for action, identifying specific activities and potential partners for moving forward. In November 2003, after five years of implementation, the NEEAPSD was reviewed by a national consultative team. This initiative was timely in preparing Jamaica for the launch of the UNDESD, 2005-2015.

Emerging from the NEEAPSD vision, the National Environmental Education Committee (NEEC) was founded in 1999 to address environmental education in elementary and secondary schools. NEEC functions like the local arm of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). Since 2002, NEEC has conducted assessments of students’ responsibility for SD and chances of getting students to influence the change and sustainability movement. As one of the few plans of its kind, the NEEC’s initiative can become a model for other countries as they seek to create a framework for their own environmental education activities.

Research Design

Sampling Plan

Based on the assumption that an educated citizenry can fully participate in community, national and global development, a critical examination of program deliverables related to SD was done with 182 adult educators and learners of HEART/NTA. The research design involved a pre-test of an investigator-designed instrument, two pilot studies, a quantitative survey, which was followed by structured open-ended interviews with 10 survey takers.

Representatives were selected by stratified random sampling from the administrator/facilitator and trainee corps in agriculture, automotive trade, building and construction services, and hospitality programs. Initially, 14 subjects participated in a pretest and a pilot study to assist with the development of the survey instrument. An additional 168 subjects took the survey, and from this group, 10 indicated a willingness to follow through with the open-ended questions.

Method

Three subsidiary questions and three hypotheses evolved from the major research question, how do adult education programs in Jamaica address sustainable development?

To what degree do adult education programs address the knowledge and behaviors associated with environmental sustainability?

To what degree do adult education programs address the knowledge and behaviors associated with economic sustainability?

To what degree do adult education programs address the knowledge and behaviors associated with social responsibility?

Hypotheses

There is no significant relationship between sustainable development and the knowledge and behaviors associated with environmental sustainability, economic sustainability and social responsibility.

There are no significant differences in the ways that instructors and trainees perceive the deliverables and the outcomes of programs associated with sustainable development.

There are no significant differences in the ways that different programs address sustainability.

Instrumentation

Quantitative surveys were administered to current trainees and facilitators within the target programs at four locations across the country. The surveys were designed to discover how much attention was paid to related SD concerns. The 214-item instrument contained three sections:

Seven questions for capturing the demographic profiles of adult educators and learners.

Part I covered knowledge associated with SD. It examined the coverage of content and the importance or relevance of the content to the program. The responders were required to rate 34 items on a Likert-type scale but because nine questions overlapped, scoring was done for 43 items.

Part II emphasized 45 imperatives on behaviors associated with SD. The responders were required to provide dichotomous responses on each imperative from four distinct perspectives, namely: (a) program coverage; (b) program plan for transfer of learning; (c) personal applications; and (d) collective applications.

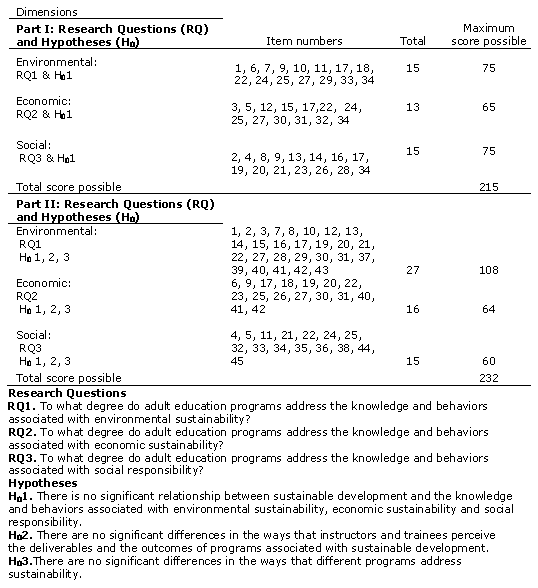

Scoring and achievement rates were done within dimensions as displayed in Table 1 below. Scores were accumulated based on how responders rated the items, from 1 to 5 on Part I and from 0-4 on Part II. Responders were required to obtain minimum scores equivalent to 40% of the total score in each category to be addressing SD in a significant manner.

Table 1. Item Category

Findings

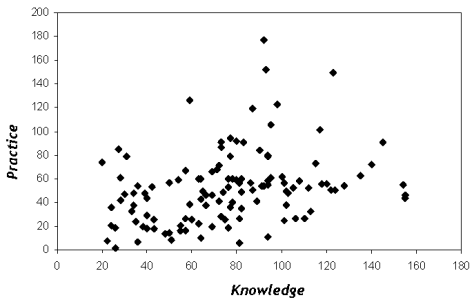

On average, respondents performed poorly on both sections of the survey. The performance of facilitators and trainees were similar and while there appeared to be few outliers, it was interesting and disappointing to observe that only four respondents attained the minimum required scores equivalent to 40% in all six metrics. These results are displayed on the scatter plot in Figure 1 below.

Figure1. Scatter Plot depicting relationship between content delivery (Knowledge)

and behavioral outcomes (Practice).

The scores on Part I of the survey, content delivery ranged from 20 to 155 out of 215. The scores on Part II of the survey, behavioral outcomes ranged from 7 to 177 out of 232. While 30 respondents or 25% claimed that the programs addressed the content significantly, 20 respondents or 17% indicated that they applied the knowledge or were involved in sustainable behaviors. It was evident from the ratings that the programs paid slightly more attention to content delivery than to behavioral outcomes. Clearly, knowledge about SD was not motivating sustainable practices since wide discrepancies were observed between knowledge and behaviors.

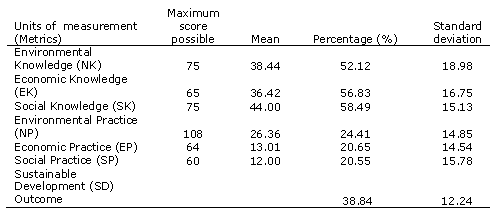

The means and standard deviations are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics

Research Question One

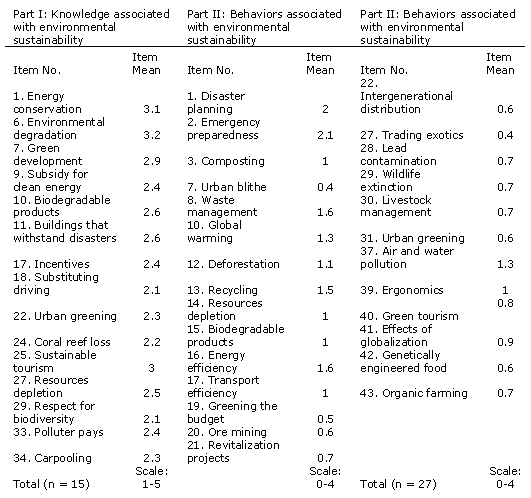

To what degree do adult education programs address the knowledge and behaviors associated with environmental sustainability? Content delivery or knowledge was measured using 15 items while behavioral outcomes or practices were measured using 27 items. The data for the first research question are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Data for Environmental Sustainability

On average, performance on all items fell below 4 on the knowledge scale, indicating that no environmental concern was addressed frequently. The highest means were associated with three items, energy conservation, environmental degradation, and sustainable tourism, which were covered sometimes. On average, other concerns on green development, biodegradable products, flood-resistant buildings, and on resources depletion were also more likely to be addressed sometimes, since they had means above the 2.5 midpoint on the Likert-type scale. Concerns for subsidy for clean energy, substitutes for driving, urban greening, coral reef loss, respect for biodiversity, debt burden, and on carpooling were rarely addressed. All concerns were noticeably addressed, since, on average, no item had a mean of 1 for never. In summary, the programs addressed the content on environmental sustainability either sometimes or rarely.

Alternatively, the performance on behavioral outcomes was considerably worse than on the content delivery. The expected standard of 3 was not obtained on any item. Two environmental imperatives, disaster planning and emergency preparedness had means in the range of 2, while 11 environmental imperatives had means, which ranged from 1 to 1.6 on the behavioral scale. It became evident that on 14 out of 27 environmental imperatives, these respondents did not apply the principles leading to environmental sustainability.

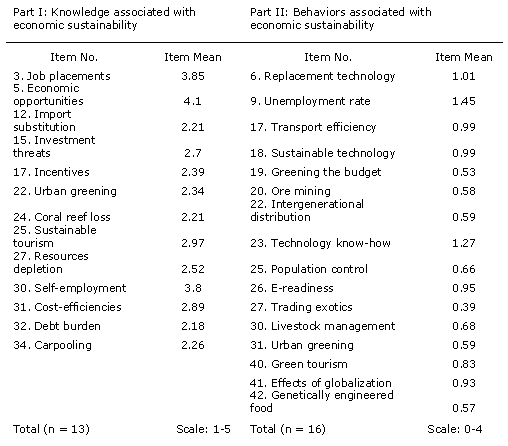

Research Question Two

To what degree do adult education programs address the knowledge and behaviors associated with economic sustainability? Content delivery or knowledge was measured using 13 items while behavioral outcomes or practices were measured using 16 items. The data for the second research question are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4. Data for Economic Sustainability

A single item, opportunities for economic success, met the acceptable standard. On average, it was addressed frequently. It was followed closely by job placements, and by self-employment or job creation opportunities. While 77% of the content on economic sustainability is covered rarely or sometimes, practices leading to economic sustainability are probably never pursued, as indicated by the means associated with the behavioral outcomes in this dimension. Within the economic dimension, performance on behavioral outcomes fell below 1.5 on every item, much lower than the 3 that is required for significant coverage. Remarkably, only 3 economic outcomes had means above 1. They were technology know-how, unemployment rate, and replacement technology. The evidence that 81% of the economic imperatives had means below 1, is an indication that these respondents were not achieving economic sustainability. Based on these performances, it is evident that more relevance is placed on knowledge associated with economic sustainability than on practices or behaviors. Neither trainees nor instructors expected the knowledge to change their thinking and their behavior.

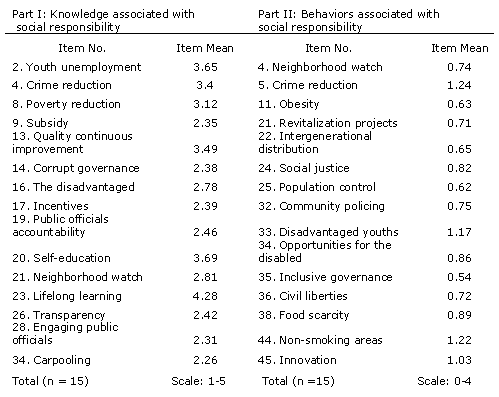

Research Question Three

To what degree do adult education programs address the knowledge and behaviors associated with social responsibility? Measures on content delivery and on behavioral outcomes associated with social responsibility were obtained for 15 items from each perspective. The data for the third research question are displayed in Table 5.

Table 5. Data for Social Responsibility

Once again, a single item was addressed at an acceptable standard. On average, the content on lifelong learning had the highest overall mean of 4.28, which translated to frequently on the 5-point Likert scale. It was followed by self-education and youth unemployment. Five social concerns were addressed sometimes while seven concerns were addressed rarely. In summary, the content on social responsibility were addressed, frequently, sometimes, and rarely. This is the only dimension where more than three concerns had means above 3. However, of the 15 items on behaviors associated with social responsibility, only 4 imperatives had means above 1. These were crime reduction; smoking in public places; disadvantaged youth and human innovation. Since 73% of the social imperatives had means below 0, respondents have not transferred the knowledge to sustainable practices for assuming their social responsibility.

While it was apparent that the content associated with social responsibility was addressed with more frequency than the content within the other two dimensions, the behaviors leading to environmental sustainability were adopted in more cases than in either the economic or the social dimension. Further analysis of the data showed that, overall, the percentage of respondents pursuing environmental sustainability was 15%; pursuing economic sustainability was 16%; and assuming their social responsibility was 13% ; while a mere 7% of the sample achieved sustainable development. From these results, it became evident that the programs had addressed some concerns in all dimensions but that transfer-of-learning was left to chance. Few respondents displayed any recognition for the interdependencies.

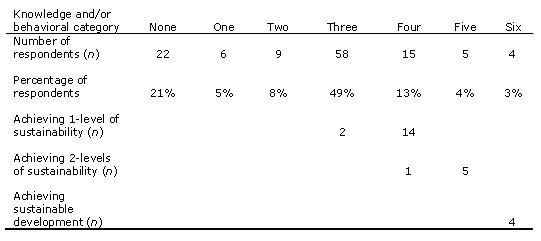

A summary of the results showing the combined performance on knowledge and behaviors within distinct dimensions is delineated in Table 6.

Table 6. Achieving Sustainable Development

Based on the standard outlined in the rubric that achievers should obtain scores equivalent to 40% of the total score within each area of assessment, it is evident that only a mere 3% of these respondents claimed that they pursued the processes for achieving SD and as a consequence, are likely to transfer the learning. The percentage of respondents who have not achieved sustainability at any level is 75%. Twenty-six respondents or 25% of the sample appeared to achieve at least one level of sustainability. These results have implications for instructional leadership.

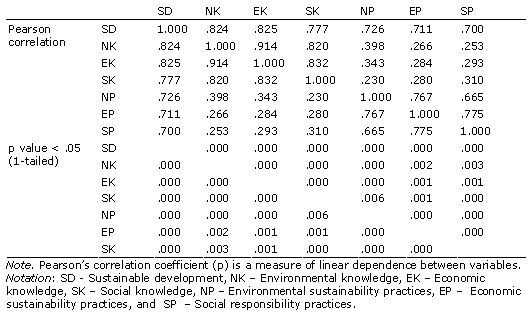

Hypothesis One

The null hypothesis, H01, there is no significant relationship between sustainable development and the knowledge and behaviors associated with environmental sustainability, economic sustainability and social responsibility was tested by correlation analysis. The correlations and p values are presented in Table 7.

Table 7. Correlation Analysis

All six measures correlated highly with the SD outcome. The weakest correlations existed between the social (S) and environmental (N) variables. However, the degree to which the associations covary were so close that it was impossible to detect how much variance a particular variable contributed to the dependent SD variable. For example, knowledge associated with environmental sustainability (NK) and economic sustainability (EK) differed by one-thousandth. The correlations were 82.4% and 82.5% respectively. Correlations for the other four associations ranged from 70-77%. All correlations were significant, hence, the hypothesis that no significant relationship exist between sustainable development and the knowledge and behaviors associated with environmental sustainability, economic sustainability and social responsibility was rejected.

Hypothesis Two

Mean differences were utilized in the analysis of the second null hypothesis, H02, there are no significant differences in the ways that instructors and trainees perceive the deliverables and the outcomes of programs associated with sustainable development. The hypothesis was accepted because in all three dimensions trainees and facilitators usually agreed. Similarities were observed for 10 of the 15 concerns on content delivery associated with environmental sustainability; 11 of 13 concerns on the content associated with economic sustainability; and on 10 of 15 concerns on the content related to social responsibility. Wider disparities were observed among the behaviors. Differences were observed for the 17 of the 27 applications related to environmental sustainability. However, the data exhibited some interesting highlights on economic sustainability. Trainees were observed to be applying about 2% to 26% of the principles while the facilitators were applying about 6% to 39% of the principles. For example, because technology transfer is an important indicator of sustainable development, careful attention was paid to these results. The principles of technology were applied by 22% of trainees and 39% of instructors, but while 26% of the instructors claimed that e-readiness was covered, no trainee (0%) recognized that it was covered. E-readiness applications were pursued by 33% of the facilitators but only 2% of the trainees. Further investigation of these results are required since the literature identified Jamaica as one of two developing nations in the region with a high e-readiness index. Regarding the concerns for assuming social responsibility, trainees were mostly concerned about food scarcity and human innovation, while facilitators paid more attention to disadvantaged youths and crime reduction.

Hypothesis Three

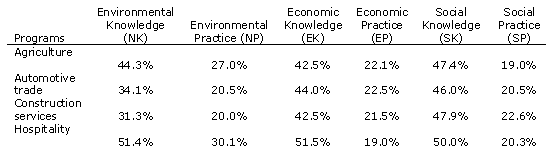

The third null hypothesis, H03, there are no significant differences in the ways that different programs address sustainability was also tested by mean differences. This hypothesis was also accepted based on the results displayed in Table 8.

Table 8. Determining Program Effectiveness

Overall, respondents within the different programs performed similarly on behavioral outcomes within the economic (EP) and social dimensions (SP). Hospitality programs were more effective than agriculture, automotive trade and construction services programs in addressing the knowledge associated with sustainable development. However, while agriculture, construction and automotive programs had more similarities on both content and behaviors, all four programs performed poorly on the behaviors. Hospitality programs differ from agriculture programs on content delivery in environmental (NK) and economic sustainability (EK) by 7 and 9 percentage points, respectively; from automotive by 17 and 7 percentage points respectively; and from construction programs by 10 and 9 percentage points, respectively. On behavioral outcomes associated with environmental sustainability (NP), the difference between agriculture was 3%, while the difference was 10% for both automotive and constructive programs. Evidently, hospitality programs make the greatest contribution toward environmental sustainability.

From the above results, it was apparent that attempts were made to attend to the environmental, the economic, and the social dimensions. Some content was covered but little transfer of learning occurred. To these respondents, knowledge about SD was not applicable to real-life situations and had almost no effect on their thinking and their behaviors. The effect size was computed as 0.04 or 4%, an indication that these adult education programs had no significant effect on SD.

Discussion

In this developing nation, sustainability is pursued by individuals or by stakeholder groups who have investments in certain industries. Despite the claim made by policy makers that the country is achieving SD, the study found that adult educators assumed responsibility for covering relevant content but were least concerned about the transfer of learning. Concerns for educational opportunities, high incidences of natural disasters, and crime were emphasized but no evidence existed that respondents made the connections between environmental degradation and mining activities, air pollution, clean water and waste disposal or management. Good governance was not envisioned as a training objective. Until good governance is seen as a key factor in the process, facilitators will be unable to help learners pursue their social responsibility through leadership accountability and commitment.

Leadership commitment and political accountability were investigated within the social dimension as governance concerns. Clearly, accountability for the war against crime is a leadership imperative but the programs rarely addressed the concerns on governance. In fact the poor performance on the behavioral outcomes within the social dimension was a consequence of the poorer performance on concerns related to governance. Interviewees who justified their outcomes on the survey did not think that the government was treating SD seriously. Although the Government of Jamaica initiated dialogues with key decision makers about the importance of SD and the responsibility it imposes on the public and private sectors since 2003, five years later, these dialogues are not supported with tangible incentives or tax credits to encourage the implementation of sustainable technology. We all need to work towards good governance in the movement to create and maintain a culture of sustainability. Hall and Denis (2000) recommend that the process has to be accompanied by conscious policy investments in the productive sectors. Regulatory agencies should be required to define standards and specifications for green buildings, energy-efficient vehicles and household appliances.

In many developed nations, a range of monetary and non-monetary incentives such as tax credits, rebates, technical and administrative assistance are offered to corporations, developers and individuals who adopt sustainable practices. For example, in the United States, there is a National Renewable Energy Laboratory project whereby “some homeowners can recoup up to $20,000 in solar costs” (Walsh, 2008, p. 52) from loans and subsidies. Nations such as Germany, France and Japan that are serious about achieving sustainable development give preferential treatment to citizens and review business plans and permits expeditiously for proponents of green development projects. Incentives are an invitation for people to get on board. In addition, incentives demonstrate government’s commitment to the process. Even China has made progress by levying significant penalties on polluters. Companies that have violated environmental laws are banned from the Canton Fair, the most important channel for Chinese importers to expand overseas. In addition, polluters are denied loans under the Chinese banking regulatory Commission (Hanson, 2008).

The respondents who identified corporate greed and crime as barriers to SD in the open-ended questions, also included the political leadership in the call for cooperation from everyone. Political leaders, in particular, need to enforce anti-corruption legislation to have equity and justice for people from all socioeconomic background and political affiliations. The enforcement must be followed closely by public education in the media and by other formal systems for reaffirmation of the effectiveness of the justice system. When confidence is restored in the justice system, it will be possible to build institutional capacity for achieving SD.

Implications for Instructional Leadership

Having a mindset for sustainability should bring about new behaviors and practices eventually. A culture is built by getting people to continually think and act in habit-forming ways, until the thinking becomes a mindset. In some countries, individuals are ready to take personal action and responsibility for reducing carbon emissions and measure their ecological footprint. Citizens have indicated their willingness to make constructive and adaptive changes to behaviors and lifestyles to address the issues of global warming. Corporations and governments are no longer perceived as the dominant problem solvers, even though partnerships with them are essential for making progress. Since, over the years, instructional leadership has been responsible for shaping policies and behaviors, it can become a major player in the sustainable development movement.

Over the years, instructional leadership has driven behaviors with standards to reinforce practices and to build a culture of success and high achievement among students. The notion underlying standards is that the central responsibility of leadership is to improve teaching and learning. Standards set the stage for facilitators to devise strategies that allow learners to think about the ways in which they can modify their behaviors so that future generations can have the same or more resources than the present generation.

The process begins with clear communication of the concept or the articulation of a vision of sustainability. The vision of a sustainable future should encourage learners to explore processes and concerns leading to sustainable development. Exploring in-depth what sustainable development might be fosters critical thinking and reflection for motivating useful action. Learners should recognize that there are no quick fixes. They should understand that even though technology is here to stay, the careful examination of the impacts or effects of the innovation should precede the release of a new product, a new technology. Apparently, careful examination and reflection were not taking place among the respondents in the study. The evidence that the select adult programs address the knowledge but not the behaviors associated with sustainable development is consistent with reports that few adult learners and community members are asked to reflect upon the impacts of their activities and those of their families and the wider society on the functioning of ecosystems (ECLAC, 2000; UNESCO, 2002, 2007).

Projects and debates present two types of learning strategies that instructors and learners may share responsibility for thinking about and reflecting on the sustainable development concept. The execution or presentation of the project offers opportunity for learners to take action. These strategies may be incorporated in learning process. However, instructional leadership has to commit to professional development and the allocation of resources for facilitators to plan for transfer of learning. A project on sustainability should enable learners to explore mitigation costs and affordability of environmentally friendly products; and also examine the social and economic impacts on the environment. The following examples illustrate how three students assist corporations to build the culture of sustainability:

Example 1: MBA student, JJ roamed the hallways of a California software firm upgrading the air-conditioning and heating systems, installing controls to turn off bathroom lights and vending machines when not in use. He identified more than $500,000 a year in potential savings to the company by conserving energy.

Example 2: MBA/MS student, ER found out that Cisco could save $24 million over five years by installing “smart power distribution units (PDUs) in their laboratories because most equipment ran all the time, regardless of whether it was in use. The PDUs sensed when a piece of equipment was inactive and turned it off until it was needed. Installation of PDUs will reduce Cisco’s carbon footprint by 300 million pounds, over a five-year period.

Example 3: MBA student, ML worked with NVIDIA’ Green team to remove 10,000 unnecessary fluorescent bulbs in over lit areas of the office space. The removal will save NVIDIA $83,000 annually. An estimated reduction of 825,000 kwh/year is expected to accrue from the removal, which will reduce global warming emissions by 829,000 pounds annually.

These examples emphasize the importance of partnerships in the process. Instructional leadership will need to explore their social responsibility with learners for building the culture of sustainability through leadership commitment and political accountability. The process starts with the election of representatives with a mindset for the pursuance of good governance. Citizens vote and then ensure that the principles of good governance are upheld. Subsequently, educators and learners have to understand that the purchasing power of a nation, a community or a citizen is critical to maintaining a culture of sustainability. Achievements and progress depend on what nations or individuals are able to afford. For example, a nation whose gross domestic product (GDP) depends on mining activities to support social systems and raise the standard of living for citizens, cannot suddenly cease mining operations unless it is possible to replace this unsustainable activity with a more lucrative economic activity. Similarly, clean air and clean water are important health concerns. Healthy people are more productive than persons plagued by ill health and diseases. Educators and learners will have to find a strategic starting point and attend to the concern that affects them most. Consequently, our social and economic dependence on the natural resources and our trading patterns are going affect our capacities for reducing carbon-dioxide emissions or for becoming more energy efficient.

Conclusion

As schools and educational institutions help students achieve carbon neutrality; consider the greening of buildings, budgets and operations; or create a culture of sustainability; insights may be gained from this study for devising roadmaps to integrate sustainability across disciplines. A culture of sustainability calls for inclusive, comprehensive, institution-wide effort and the establishment of partnerships.

References

Caffarella, R. S. (2002). Planning programs for adult learners: A practical guide for educators, trainers, and staff developers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Calder, W. (2005). The UN decade of education for sustainable development: A progress report. The Declaration, 7(2), 1-5. Retrieved August 7, 2007, from http://www.unesco.urg/iau/sd/declarations.html

Center for Urban and Environmental Solutions, The. (2004). Regional shift: South Florida in transition: A report by the Anthony J. Catanese Center for Urban and Environmental Solutions. Unpublished manuscript, Florida Atlantic University.

Center for Urban and Environmental Solutions, The. (2007). Living on the edge: Coastal storm vulnerability of the Treasure Coast barrier islands [CD-ROM]. Fort Lauderdale: Florida Atlantic University.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2008). Jamaica economy 2007: Overview. Retrieved July 1, 2008 from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/jm.html

Collinder, A. (2008, August). Gambling with the soil. The Jamaica News. Retrieved August 10, 2008 from http://www.jamaicagleaner.com/gleaner/20080810/ lead/lead4.html

Economic Commission for Latin American and the Caribbean. (2000). Sustainable development: Latin American and Caribbean perspectives. Based on the Regional Consultative Meeting on Sustainable Development, 19-21 January, 2000, Santiago, Chile. Retrieved August 17, 2007 from http://www.unep.org/esa/ sustdev/publications/sdlac_perspective_book.pdf

Ekins, P., & Medhurst, J. (2006). The European structural funds and sustainable development: A methodology and indicator framework for evaluation. Retrieved October 10, 2007, from http://evi.sagepub.com/

Fowler, F.C. (2004). Policy studies for educational leaders: An introduction. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Gafta, D., & Ackeroyd, J. R. (2006, May). Standards, technology and sustainability. The Environmentalist, 26(2), 93-98. Retrieved September 12, 2007, from http://www.springerlink.com/content/

Gibson, R.B., Hassan, S., Holtz, S., Tansey, J., & Whitelaw, G. (2007). Sustainability assessment: Criteria and processes. London: Earthscan.

Hall, K., & Denis, B. (2000). Contending with destiny: The Caribbean in the 21st century. Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle.

Hanson, T. (2008). The biggest economic opportunity for the Twenty-first Century. International Investing. Retrieved August 30, 2008, from http://www.ghg protocol.org/standards/corporate-standard

Hopkins, C. (2003). Education for a sustainable future: Shaping the practical role of higher education for sustainable development: A background paper. IAU Prague Conference, September 10-11.2003.

Jamaica Social Policy Evaluation. Technical Working Group. (2004). An annual progress report on national social policy goals 2003. Retrieved August 3, 2007 from http://www.jaspev.org

Jamaica. Task Force on Education Reform. (2004). Jamaica: A transformed education system: Final report. Retrieved August 11, 2006, from http://www.moec.gov.jm/ EducationTaskForce.pdf

Malhadas, Z.Z. (2003.) Contributing to education for a sustainable future through the curriculum, by innovative methods of education and other means. International Conference on Education for a Sustainable Future: Shaping the Practical Role of Higher Education for Sustainable Development [held at] Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 10-11 September 2003.

Martin, S., & Jucker, R. (2003). Educating earth-literate leaders. International Conference on education for a sustainable future: Shaping the Practical Role of Higher Education for a Sustainable Development, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic, 10-11 September, 2003. Retrieved August 3, 2003 from http://www.unep.ch/etb/Jucker_Martins.pdf

Merriam, S. B. (2004). The changing landscape of adult learning theory. In J. Comings, B. Garner, & C. Smith (Eds.), Review of adult learning and literacy: Connecting research, policy and practice (pp. 199-236). Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Merriam, S. B., & Caffarella, R. S. (1999). Learning in adulthood: A comprehensive guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B., Courtenay, B. C., & Cervero, R. M. (Eds.). (2006). Global issues and adult education: Perspectives from Latin America, Southern Africa, and the United States. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mog, J. M. (2004). Struggling with sustainability: A comparative framework for evaluating sustainable development programs. World Development Report, 32(12), 2139-2160.

National Environmental Education Committee. (2002). Environmental education for sustainable development school-based project. Retrieved September 6, 2008, from http://www.moec.gov.jm/projects/nepa/School_based%20Project.htm

Planning Institute of Jamaica. (2004). Millennium goals: Jamaica. Retrieved June 15, 2007, from http://www.pioj.gov.jm/NDP_info.aspx

Riley, S. (2002, September). A high school; equivalence programmes: JAMAL Foundation. Paper presented at the regional meeting for the Review of Strategies and Programmes for Young People and Adult learning in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Roseland, M. (2000). Sustainable community development: Integrating environmental, economic and social objectives. Progress in Planning, 54, 73-132.

Seelos, C., & Mair, J. (2005, October). Sustainable development: how social entrepreneurs make it happen: Working Paper 611. Barcelona, Spain: IESE Business School, University of Navarra.

UK Government Sustainable Development (2006). Shared UK principles of sustainable development. Retrieved May 26, 2007 from http://www.sustainable-development.gov.gov.uk/what/principles.htm

United Nations. (2006). The millennium development goals report 2006. Retrieved April 16, 2007 from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/

United Nations Development Program. (1997). Governance for sustainable human development: A UNDP policy document. Retrieved August 10, 2007 from http://www.pogar.org/publications/other/undp/governance/

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2002). Education for sustainability: From Rio to Johannesburg: lessons learnt from a decade of commitment. Retrieved September 14, 2007 from https://portal.unesco.org/ es/file_download.php/

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2007). Education: Quality education. Retrieved May 31, 2007 from http://portal.unesco.org/ education/en/ev.php-URL_ID=27542

United Nations Environment Program. (2002). The sustainability of development in Latin America and the Caribbean: Challenges and opportunities. Chile: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

United Nations Environment Program. (2003). Environmentally sound technologies for sustainable development. Retrieved August 10, 2007 from http://www.unep.org. jp/ietc/techTran/focus/SusDev_EST_background.pdf

United Nations Environment Program. (2006). Towards an international framework for integrated assessment/sustainability appraisal (IA/SA): A concept note. Retrieved August 3, 2007 from http://www.unep.ch/etb/areas/

Walsh, B. (2008, August 18). Going green: Solar power hits home. Time. 52.

Welsh Assembly Government. Department of Lifelong Learning and Skills. (2006). Sustainable development and global citizenship: A strategy for action. Retrieved May 28, 2007, from http://www.esd-wales.org.uk/english/

Zandvliet, D.B., & Fisher, D.L. (Eds.). (2007). Sustainable communities, sustainable environments: The contributions of science and technology education. Retrieved March 27, 2007 from www.sensepublishers.com/

Copyright © 2009 by Pauline A. Mclean

|